John Bush stood on the flat, grassy loam of Fort Stewart Army Base — 40 miles southwest of Savannah, Georgia — as the August morning sun beamed down, waiting for 16-year-olds Jamal Richardson and Jahkobie Campbell.

Like many of the kids he’s helped, Bush had watched the boys struggle throughout middle school and into high school, their academic records littered with failing grades and repeated suspensions, mostly for fighting.

Bush’s job as an intervention specialist with the Chatham County district attorney’s office is to steer at-risk youth in Savannah away from lives of violence and onto better paths. But he doesn’t think of it as a job.

“It’s more of a ministry,” Bush said.

In the middle of the night, he visits victims of intentional injury — shootings, stabbings, assaults — who are admitted to the hospital emergency department. During the day, he frequents schools, courtrooms, homes, churches or wherever else he’s called when adolescents show violent tendencies. He hands out his cellphone number for people to call if they sense a conflict brewing.

His goal is to find Chatham County residents ages 12 to 25 who are in vulnerable or violent situations and introduce them to the district attorney’s Youth Intercept program, which aims to address physical, emotional and social needs.

The notion that strong adult mentors can intervene, offer support and provide structure to prevent youth violence isn’t new. Municipalities, nonprofits, grassroots organizations and passionate individuals across the country, and here in Chattanooga, have attempted the noble task because they say it’s the right thing to do, but also because it has the potential to save money.

Preventative programs, while they do require funding, in the long run often cost less than dealing with the aftermath of gun violence.

It costs Tennessee taxpayers nearly $110,000 per year to incarcerate a juvenile in a detention center, according to a 2014 report from the Justice Policy Institute, a nonprofit organization based in Washington, D.C. Prison costs significantly more money, and that figure doesn’t include the financial losses to the individual and family.

The United States spent about $33 billion on incarceration in 2000 for essentially the same level of public safety it achieved in 1975 for $7.4 billion, according to a 2017 report from the New York-based Vera Institute for Justice. Researchers state that mass incarceration doesn’t just come as a cost to the government, but there are social, cultural and political costs on individuals, families and communities.

“Incarceration reduces employment opportunities, reduces earnings, limits economic mobility and, perhaps more importantly, has an inter-generational impact that increases the chances that children of incarcerated parents will live in poverty and engage in delinquent behavior,” the study states.

Cities across the country are working to break that cycle, which they hope will ultimately reduce crime and the financial burdens that come with it.

Like in Cincinnati, where they practice place-based, problem-oriented policing that focuses on crime-ridden areas and how to make them safer. Or in Philadelphia and Savannah, where hospital- and school-based public health programs can intervene before a victim becomes a perpetrator.

When Richardson’s tendency to start fights landed him in an alternative school that Bush calls “a magnet school for deviants,” Bush knew it was time for a stronger intervention.

“You send somebody over there because they don’t sit down in class. When they come back, you’re gonna wish you never met ’em,” he said. “You’re talking shooters, car thieves. You’re talking people who fight every five minutes, medication issues. You got an array of issues all bottled in there together.”

Because Bush and his colleagues know the community inside out, they’re able to spot red flags — problems at home or kids hanging out with gang members — and divert those youth to one of Youth Intercept’s many partner organizations, such as the YMCA, Boys & Girls Club, Youth Advocate Programs, Prevention Clubhouses, Goodwill, juvenile courts and the military.

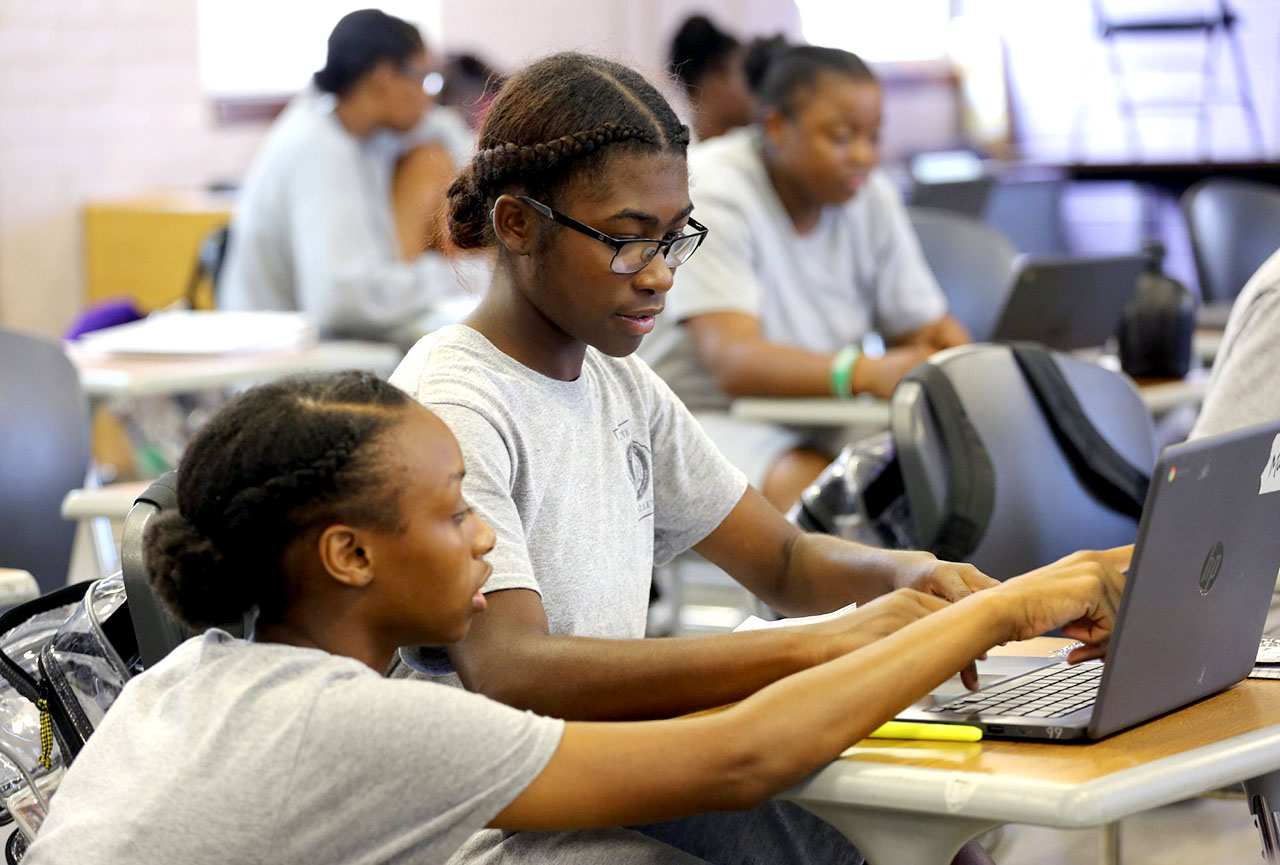

Bynoskia Sams, a team coordinator at one of Savannah’s Boys & Girls Clubs, often works with Youth Intercept participants, many of whom have nowhere to go after school. There, Sams teaches life skills, including resume prep and basic financial planning.

He said the opportunity to play basketball often gets kids in the door, but once inside, they’re exposed to myriad other activities from homework help to “street smarts,” which touches on issues like drugs, alcohol, incarceration and gang prevention.

“Everybody wants to be the next Lebron James — I mean everybody,” Sams said. “We don’t want to deter them from their goal and their dream, of course, but we just want to give them some backup plans, some other skills. Even if you’re Lebron James, you need to be able to count your money. … You’re throwing different things in there to make them understand that there’s a bigger picture.”

So instead of heading back to school for the 2018-2019 academic year, Richardson enrolled in the Georgia National Guard’s Youth ChalleNGe Academy — a 22-week, hyper-structured program at Fort Stewart designed to direct teens away from violence while completing their high school education. Campbell and one other teen from the district attorney’s program also joined.

Youth ChalleNGe participants are placed on a fast track to catch up in school, and most leave with a high school diploma or GED and a job in place. Director Roger Lotson said emphasizing academics is essential for at-risk youth, because the No. 1 factor for an individual being incarcerated is lack of education.

“We started off as a trial program back 25 years ago, and we had to prove to Congress that their money is well spent,” Lotson said. “We proved that for every $1 spent, we get a $2.66 return on investment, so it’s a program that is well worth it.”

Tennessee launched it’s own Youth ChalleNGe program, the Tennessee Volunteer ChalleNGe Academy, in 2017. It’s based in Nashville but serves teens from across the state. Eight teens from Hamilton County have graduated from the program and six are currently enrolled.

That August morning, Richardson and Campbell lumbered toward Bush from their barracks. It was just after 10 a.m., but they’d been up since 5 a.m., completed an hour of physical training, eaten breakfast and begun their daily assignments, which range from academic and life skills classes to manual labor and community service.

“It’s a different environment where they actually can sit down and take in the information that we’ve been trying to shove down their throats an hour here, two hours there, and then they’re being interrupted by real life back home,” Bush said.

Bush greeted the boys with a playful elbow jab and a gentle reminder to remove their hats before entering the building. They’d been on base for four weeks and Bush said he can already see a change.

“We banter back and forth all the time. You’d think I’m the one getting bullied,” he said. “Neither one of them have thrown any shots back at all. They’ve been very restrained, disciplined, focused, respectful.”

Campbell, whose older brother also attempted the program but was kicked out before graduating, said he’s determined to finish. He’s also studying culinary arts.

“Sometimes, my mom wouldn’t be home when she’d have to go to work, so, I’d be, like, hungry,” Campbell said. “I don’t wanna have to depend on nobody to cook my food for me.”

Richardson said traditional school wasn’t for him, but he likes the attention he gets at Fort Stewart, because the classes are smaller.

“They really break it down. There’s ‘me’ time,” he said, opposed to his old school where he was busy “surviving” instead of learning.

He said he knows changing his life will take time.

“I gotta adapt, like how I adapt anywhere else. And it’s hard, ’cause I’ve been here less time than I been out there,” Richardson said. “It’s gonna be a change for the better, and that’s a good thing.”

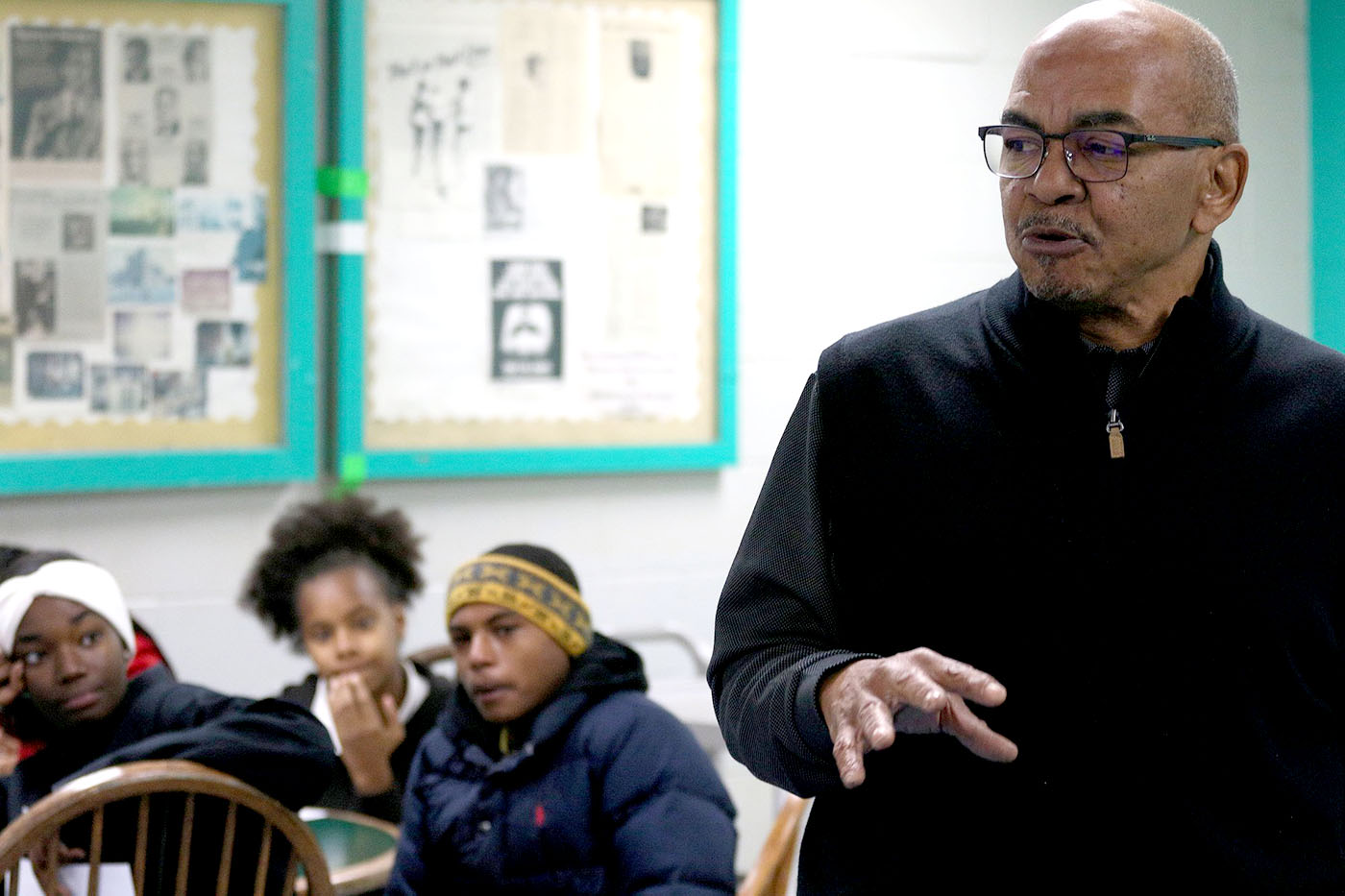

In Chattanooga, people like Joe Hunter — better known as “Uncle Joe” — work to try and reach the at-risk youth.

In many ways, Hunter’s work mirrors the Cure Violence approach in which a “violence interrupter” — often a former felon or gang member — goes out into the community and uses their street knowledge and background to help stop the violence.

The only way gangsters retire, Hunter says, is in jail or in the grave.

Hunter came to Chattanooga about a year ago, but he’s been mentoring and working with youth in Memphis since 1995, a year after he was shot five times.

“I look for gang members on purpose and I hug you,” Uncle Joe said with a smile. “Yes, we can kill one another, but we can also love and share with another.”

He believes the solution to gun violence is to provide an environment that is conducive to enrichment, because all kids are teachable. You can teach them to be a gangster or a good kid, he said.

“The only way I know how to get a kid to put a gun down is to have a relationship with him,” he said.

A city employee, Hunter is paid about $40,000 a year and spends his days between the Carver and Eastdale Youth and Family Development centers. At night, he hosts Teen Empowerment, a voluntary program for 13- to 17-year-olds. He’s been overseeing the program for a year now.

On Wednesdays, he’s at Carver. And on this particular day in November, Hunter was talking about the new “word of the month” — love. He told teens not just to love their families, friends, boyfriends and girlfriends, but to love themselves, too.

Hunter believes he can connect with the kids on a level that most adults can’t, because his past helps him understand why they might choose that life: fear. For some, he said, the gun in their mother’s nightstand is the only “father figure” they know.

“For these guys to carry guns, it is almost legitimate,” he said. “You aren’t walking down the streets, he is.”

A day after Hunter selected one boy to be his helper at Carver YFD, he was shot in his backside and his friend was also shot, leaving the child paralyzed.

Hunter has escaped death more than once over the years.

He became a “junior” gang member in Detroit at age 8, he said, to protect his neighborhood from white racists. Growing up in the 1960s, Hunter said that was one of the main reasons gangs formed.

In 1994, he was in a car when someone with an AK-47 and a grudge fired multiple shots at him. Five of the bullets hit Hunter, and he counted 15 bullet holes in the side of the car.

Scars remain on his left forearm, along with a bullet that was never removed. It still protrudes from beneath his skin.

“I leave one in there to teach kids what an AK-47 feels like,” he said.

And in 1985, he survived the infamous plane crash of Ray Charles and his band in Indiana.

“I think I’m supposed to be here,” he joked as he cleared the table of food and wiped up spilled juice.

Hunter had a nonprofit and youth enrichment ministry called “G.A.N.G., Inc.” in Frayser, one of the most violent neighborhoods in Memphis. The nonprofit mentored some of the at-risk youth in the area, but Hunter had to stop services in 2017 because of funding arguments with the city.

These days, Hunter tries to stay out of politics. His only friend is Jesus, he said.

“There is a whole lot of [stuff] going on politically that don’t touch the ground here,” Hunter said, as he signaled toward the rest of the room.

“Bean counters don’t get me anywhere. People like me have been told no so many times by people who were supposed to say yes.”

After Hunter’s program in Memphis was shut down, Chattanooga public safety coordinator Troy Rogers invited him to speak at a call-in meeting.

Call-in meetings are a crucial component of the city’s VRI program. Offenders who are known gang members attend “call-ins” where local officials, victims, ex-gang members and community leaders try to reason with them, and gang members — who are required to come as a condition of their probation — are told if they continue to commit violent crimes, they will be prosecuted to the fullest extent of the law.

Hunter said he likes the way Chattanooga conducts call-in meetings, inviting several members of the community and not just police officers and government officials. After he spoke at his first one over a year ago, the city liked Hunter’s message and asked if he would want to head up the city’s Teen Empowerment program.

Today, Hunter still addresses gang members at the city’s call-in meetings. He tries to level with them, joking about how all he wanted to be when he grew up was a gangster. Being a law-abiding citizen isn’t that hard, he told offenders at one in October.

“I look for gang members on purpose and I hug you,” Uncle Joe said with a smile. “Yes, we can kill one another, but we can also love and share with another.”