FORT OGLETHORPE — The ending began with a smash.

At the entrance of his hospital, Hutcheson Medical Center CEO Charles Stewart sliced a sledgehammer through the air, smacking its head into the wall.

This, he told about 100 employees at a celebration, was just the start. The start of salvation.

Stewart was in his third year as the head of Hutcheson in July 2008. Today, he doesn’t remember that celebration, though multiple employees swear it happened. At any rate, in that particular moment, on a summer day eight years ago, Stewart was in the midst of a grand turnaround, the same kind of magic he performed about a decade earlier while saving an Alabama hospital.

Here, in North Georgia, where he oversaw 900 employees, Stewart led Hutcheson to a profitable year for the first time since 2000. But the hospital needed to take another step. Stewart worried about the image of the place, worried about how some locals referred to Hutcheson as “Die County,” a twist on its original name: Tri-County Hospital.

Stewart wanted to compete with the big hospitals in Chattanooga, which had been siphoning away North Georgia patients since the beginning of the decade. Those hospitals looked state of the art. And when a hospital looks state of the art, Stewart figured, people think they will get better treatment. And when people think they will get better treatment, they will head to Chattanooga and abandon their hometown hospital, where the nurses once cared for their mothers and their grandmothers.

The appearance of Hutcheson's lobby was important to administrators, who believed its renovation would be the first step in a plan to eventually overhaul the entire hospital.

So, the lobby.

“The front entrance to the hospital,” Stewart said, “is the first impression.”

He convinced the Hutcheson Health Foundation it was a smart vision for the future. The foundation, a nonprofit that raises money for the hospital for everything from incubators to educational courses to a cancer center, agreed to give Stewart $500,000 to renovate the entrance.

That was a piece of a larger plan. Step by step, Stewart wanted to overhaul the look of the hospital. The construction would begin at the front and, with time, spread throughout the building.

In return for the investment, Stewart brought Hutcheson stone columns, new floors, cafe tables, a gift shop and extra seats for visitors. In a hospital plagued by instability, he brought hope.

The plan did not work.

Years later, with the promise of prosperity dead and Stewart selling real estate in Florida, his prized lobby became a running joke.

When staff members weren’t holding buckets under leaks in the ER or sweating through surgeries without backup supplies, they thought about the entrance, and they laughed.

While Stewart said he also spent money around the same time on cardiac equipment, ultrasound equipment and hospital beds, some doctors and nurses viewed the lobby as representative of Stewart’s failed legacy. The entrance became a symbol that they viewed as an out-of-touch administrator — and the cost of wasteful spending in a business that every day divides life and death.

“We can’t check a patient’s blood pressure,” said one nurse, who began working at Hutcheson in 1993. “But dang, doesn’t that lobby look good?”

“We wanted to take care of people, not a lobby,” said Patricia Kelley, another nurse.

“I’m not sure (Stewart’s) priorities were what they should have been,” said Betts Berry, the former chairwoman of the Foundation. “You can have the prettiest hospital in the world. But if you don’t have the doctors there, it doesn’t matter.”

For 63 years, Hutcheson Medical Center has stood as a public hospital in Fort Oglethorpe, a cornerstone in the northwest Georgia community. Builders erected the hospital in 1953 where an old medical center for soldiers in training once sat. The money for the construction came from the federal government, as well as from local mill workers who donated directly from their paychecks.

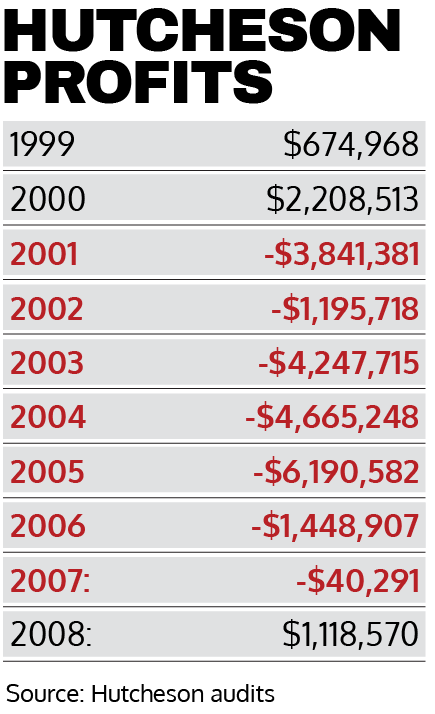

During the celebration in 2008, Hutcheson was climbing toward financial stability after years in the red.

In 2005, when Stewart arrived, the hospital lost $6.2 million, according to the Georgia Department of Community Health. In 2006, it lost $1.4 million. In 2007, it lost $40,000.

Then, in 2008, Hutcheson earned $1.1 million.

For employees and others in the community, the turnaround brought relief. This was a hospital deeply tied to Catoosa and Walker counties. The roots run back to 1904, when the government built the Post Hospital off Old LaFayette Road in Fort Oglethorpe to treat soldiers and civilians.

Forty-nine years later, after that hospital closed, Hutcheson opened its doors on the same property in 1953. Much of the funding came from the federal government after members of Congress voted to flood rural communities with money to build hospitals. They believed people in small towns throughout the country did not have enough access to sound health care.

The hospital didn’t rely on federal funding alone, though. Residents needed to raise about $1.5 million on their own, and employees of Peerless Woolen Mills and the Crystal Springs Bleachery donated from their paychecks until the hospital had enough money to open.

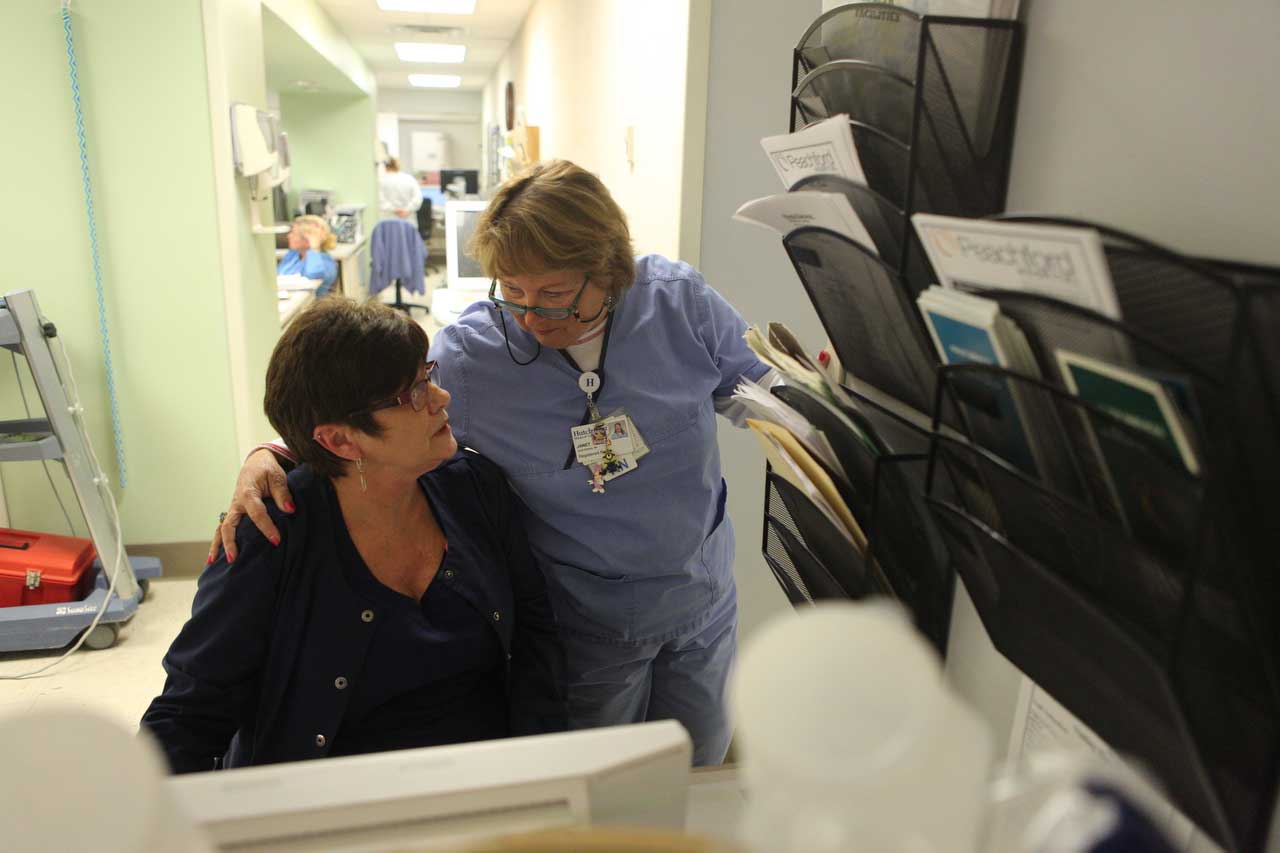

Since then, nurses and maintenance men and security guards have worked decades at Hutcheson. Their children and nieces wandered the halls after school, then jogged through those same corridors as adults, now draped in scrubs and white coats.

Hutcheson doctors delivered grandchildren. Hutcheson nurses cared for dying grandmothers.

For thousands, the hospital stood as a cornerstone.

But in 2008, as the employees felt relief and Stewart hosted a black-tie affair to commemorate the turnaround, Hutcheson’s financial foundation began to collapse. Within two years, it would be on the verge of bankruptcy.

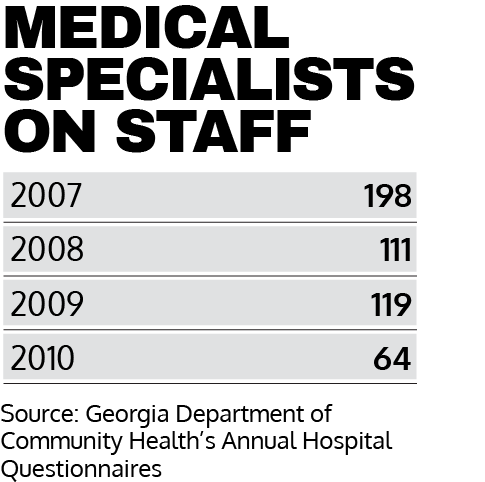

From 2007-2010, the number of specialists practicing at the hospital dropped 68 percent. The number of patients admitted to the hospital dropped 38 percent. Administrators laid off about 200 of their 900 employees.

From 2009-2011, immediately after Hutcheson finally turned a profit, the hospital lost a combined $47 million.

The downward spiral culminated in Stewart’s resignation in February 2011. And in the years after that, Hutcheson employees continued to work in an unstable environment, rotating through three more CEOs, a management agreement with Erlanger Health System, a breakup with Erlanger, a bankruptcy filing, a shutdown and — two weeks later — a revival.

ApolloMD, an Atlanta-based physicians group, re-opened Hutcheson on Dec. 22 after offering to buy the hospital for $4.2 million. Because of the legal complexities of taking over a health care operation, the company has merely operated as Hutcheson’s behind-the-scenes managers.

But on Thursday, ApolloMD’s purchase of Hutcheson was finalized, ending the Fort Oglethorpe campus’ 63-year run as a public hospital. Its new phase as a private operation will be a bit of an experiment; ApolloMD has never before owned a hospital.

If the company is to succeed, providing health care and jobs to thousands in Northwest Georgia, ApolloMD’s leaders will have to overcome the hurdles that those operating Hutcheson for the past 10 years failed to clear.

Public records and interviews show a hospital that struggled for years and absorbed a devastating blow around 2008, when the future at Hutcheson looked brightest. The problems persisted years after Stewart left, when board members, elected officials and lawyers struggled for control.

During Stewart’s tenure, large forces outside the control of any one person derailed his turnaround plan. Increased competition from Chattanooga hospitals stripped away much of Hutcheson’s patient base. And of those who continued to visit the hospital, an increasingly large percentage suffered through the Great Recession and didn’t have insurance. Or they relied on Medicare or Medicaid, neither of which reimburse hospitals well.

But many staff members believe Hutcheson suffered during those years because of something more basic: personality conflicts — with Stewart, specifically. Doctors, nurses and other staffers describe him as an egotistical leader unwilling to listen to outside voices, a CEO who challenged employees when they offered dissenting opinions. Some doctors say they stopped practicing at Hutcheson because Stewart did not respect their concerns.

“If I were the dean of a business school at a university and wanted to teach a class on how to wreck an organization, I would hire Charles to teach it,” said a former security staffer who worked at Hutcheson for more than 20 years.

For his part, Stewart says the criticism is overblown. He believes the recession and the competition from Chattanooga hospitals were factors too great for Hutcheson to overcome, and employees want to make a scapegoat out of the person at the top.

“I did everything I could to try to turn the hospital around and secure their jobs,” he told the Times Free Press in an email earlier this year. “… I don’t think they ever accepted the gravity of the situation.”

Paramedic Sandra Gray (left) talks to RN Janet Kolwyck in the ER. Hutcheson Medical Center employees worked at the hospital for decades, building deep roots in the lives of some of their patients and their co-workers. The hospital became a home, some nurses said, and the staff a family.

Stewart arrived at Hutcheson in 2005, after the hospital lost a combined $16.6 million in four years. He was recruited by Cambia Health Solutions, a consulting firm the hospital’s board hired to save Hutcheson. The firm felt the hospital’s leaders had not properly planned for a sluggish economy in the region.

The number of uninsured patients at Hutcheson increased in the years preceding Stewart’s appointment, and the hospital didn’t prepare for decreased revenues. Cambia representatives believed the board had too many administrators. About a week before Stewart was announced as the new CEO, Hutcheson laid off 42 employees.

To the board, Stewart was a turnaround artist, the type of CEO who could carry a hospital from the edge of collapse to prosperity. He came from Alabama, where he served as the vice president of a hospital system and oversaw Northport Medical Center. There, Stewart said, the hospital was thriving after losing money for four straight years — the same position Hutcheson now found itself in.

The North Georgia hospital presented him with a new challenge.

“I prayed about the position,” he said, “and I felt a calling.”

For the next three years, the hospital slowly began to lose less money, culminating in a profitable 2008. Stewart credits the group of executives he brought in to help run the hospital. He said they knew how to save money. He also said their strategic plan changed the hospital, though he cannot remember the details of that plan 11 years after the fact.

“No rock was left unturned in finding ways to eliminate unnecessary costs,” he said.

While the hospital began to make money, though, many Hutcheson employees say they worried Stewart’s management style would backfire. They saw him as a cold businessman who presented himself well but could not connect with his staff.

“Charles had the unfortunate ability to completely piss people off,” said Scott Radeker, the head of Hutcheson’s ambulance service at the time.

Nurses said he almost never made rounds at the hospital to check in with them about how Hutcheson felt at the ground level. Some didn’t know what he looked like. Patricia Kelley, who began working as a Hutcheson nurse in 2006, said Stewart could make the hospital seem impressive to outsiders while ignoring the people actually administering the health care.

She didn’t trust him.

“He knew how to tell people what they wanted to hear,” she said.

Linda Case, who worked at Hutcheson for 41 years and was the director of the radiology department under Stewart, sat in on several upper-management meetings during his time as CEO. She said Stewart was uninterested in other people’s opinions about the hospital. When a director began to complain about a new policy that would put too much pressure on his staff, Stewart cut them off.

“He was the great one,” Case said, sarcastically.

Asked about this, Stewart said he was always open to hearing outside voices. He said he held meetings with all of the hospital’s directors once or twice each month. They had to follow an agenda, he said, so the meetings would not run longer than an hour.

But at the end of every meeting, Stewart said, there was a standing invitation for people to voice concerns and ask questions.

“There were more rumors there about the hospital than anywhere I had ever been before,” he said. “If someone was cut off, it was likely due to time constraints, or it may have been about a strategic issue that couldn’t be discussed openly at that time.”

Meanwhile, some local doctors stopped practicing at Hutcheson, blaming Stewart. In 2005, according to the Georgia Department of Community Health, 180 specialists practiced medicine at Hutcheson. Five years later, that number was down to 64.

As the doctors left, so did the patients. And as the patients left, so did the revenue.

Mike Brady, who was hired to help recruit doctors to Hutcheson in the years after Stewart left, said the former CEO’s ego got in the way of a basic component of hospital administration.

“He didn’t care about physicians,” Brady said.

Stewart soon found himself pitted against Dr. David Bosshardt, who brought more patients to the hospital than anyone else. Bosshardt, an internal medicine physician who provided primary care, was deeply connected in the community. He had practiced here since 1984, and he had a list of regular patients that was 300 names deep.

Bosshardt practiced in the hospital, though he worked independently from Hutcheson. The hospital didn’t directly make money off Bosshardt’s patients, but he referred them to other parts of Hutcheson for procedures like blood tests and X-rays. “Downstream revenue” for the hospital, Bosshardt called it.

Because he had practiced so long, Bosshardt was also close with other primary care physicians in the area. When their patients needed to go to Hutcheson, they would actually refer them to Bosshardt. He would keep tabs on the patients while they waited to see other specialists at the hospital — an extra source of revenue for Bosshardt.

But Stewart did something that is fairly common at hospitals: He brought in a team of primary care physicians called hospitalists. Those doctors would be tasked with tending to patients while they waited to see specialists, like a pulmonologist or cardiologist. They would also cut into a percentage of Bosshardt’s income.

Bosshardt said the other primary care doctors in the region began calling him, telling him they received visits from Hutcheson’s marketing team. They tried to convince those doctors to send their patients to Hutcheson-employed hospitalists, Bosshardt said.

He believed Stewart was openly competing with him for people — and money.

This created a complicated problem for the CEO. On the one hand, hospitalists were a common practice, a way to bring in extra revenue at a place that wasn’t exactly rolling in money, even after a profitable year. On the other hand, Bosshardt was the most popular doctor in Northwest Georgia, a “downstream revenue” machine.

By 2008, Bosshardt was sick of Stewart. He left Hutcheson and signed a contract to instead practice at Memorial Hospital. Some primary care doctors began sending their patients to his new hospital, which benefited from Hutcheson’s loss.

He would have never left Hutcheson, he said, if Stewart didn’t try to compete with him, didn’t try to undercut the relationships he had forged with primary care doctors over three decades.

“That was something Mr. Charles Stewart failed to recognize,” Bosshardt said.

Stewart said Bosshardt’s version of events is not exactly true. He brought in hospitalists, but he wasn’t trying to compete with Bosshardt. The hospitalists weren’t even the real reason Bosshardt left, he said.

Bosshardt was overworked. His former partner had stopped practicing at Hutcheson for unrelated reasons, and he needed a new physician to practice alongside him, to split the patient load.

Stewart said Bosshardt asked for help. And Stewart said he tried, reaching out to other Hutcheson doctors, asking them if they wanted to be Bosshardt’s new partner. Nobody was interested. The rest of the team, Stewart said, did not like Bosshardt.

Regardless of whether Stewart’s version of events is accurate, the CEO was not well-liked by doctors in the community. Around the same time that Stewart and Bosshardt were tussling, the hospital’s board asked Leonard Fant to investigate the issue.

Fant, the hospital’s CEO in the 1980s, said he interviewed 67 doctors in the region. He said almost all of them complained about Stewart, claiming his administration had run many of them away. Stewart acted like he was above them, uninterested in their concerns for the hospital.

Fant said he told this to Stewart at a board meeting, but Stewart just laughed.

“Charles is a nice guy,” Fant said. “But he paid hardly any attention to anything I told him. He thought I was sort of funny. I was a comedian.”

Asked about this, Stewart said, “While I hold Leonard in the highest esteem, my opinion of the meeting and the work he performed is different from his.”

As doctors began to leave, board members heard firsthand accounts of the medical staff’s problems with Stewart. The board held meetings with doctors four times a year, said Charlie Berry, the chairman during Stewart’s time as CEO. Usually, only four or five doctors would attend.

But around 2008, Berry estimates, about 90 percent of the doctors with admitting privileges at Hutcheson showed up to the meeting. As physician after physician complained about Stewart, Berry said, members of the board realized how unhappy they were.

The relationship between doctors and hospital administrators is delicate. Executives need the doctors to bring in patients to keep the hospital running. But they also need to balance the budget. Doctors, meanwhile, want autonomy, believing freedom from the suits and their money-minded attitudes allows for better patient care.

But, the balance had tipped too far to one side: Stewart’s side.

“It was not a smooth meeting,” Berry said. “You could tell the medical staff and Charles had a real challenge.”

Still, the majority of the board supported Stewart. Some believed the complaining doctors were too sensitive. One former board member said some doctors demanded the administrators supply them with extra nurses and daily meals, expenses the hospital could not afford.

The board member, who asked for anonymity because he is still affiliated with the hospital, compared doctors to famous musicians who have tedious food demands at their concerts.

“They want blue M&Ms,” he said. “They want craft beer, 2 percent milk. All this stuff is in their contracts. People don’t know. And that’s the way those doctors are. People don’t understand that. And they want to blame Stewart for running them off.”

But other former board members now say they should have questioned Stewart more thoroughly. Some were not even aware the hospital was struggling until it was too late. They said Stewart and other administrators kept them in the dark during meetings.

Ted Rumley, the Dade County Executive, began going to board meetings in June 2010, when he heard rumors the hospital was on the brink of collapse after losing $10 million the year before. He said the hospital’s administrators discussed monthly finances at these meetings for about three minutes, and none of the board members asked questions.

When Rumley began to ask about the financial picture, he said Stewart and other administrators didn’t answer his questions. They seemed uncomfortable.

“They were just kind of holding back,” Rumley said. “I had never been to any of the meetings. It was kind of like, ‘Who are you?’ That type of thing.”

Said former board member Bill Craig: “I didn’t have any proof of what we were doing. I need to listen to a CEO tell me the results month by month.”

Asked whether the board understood how much money Hutcheson was losing at the time, Berry said, “We knew what was shown (at the meetings).”

In July 2010, with Hutcheson in the middle of losing $12 million for the fiscal year, Stewart began considering a major shakeup and hired consultants from Community Hospital Corp., a Texas company that helps struggling hospitals.

The turnaround artist needed help from more turnaround artists.

The consultants helped the board determine how to form a partnership with one of the Chattanooga hospitals. The board believed that would be the best way to save Hutcheson: Create an alliance with a bigger hospital and get an influx of cash, giving Hutcheson some room to breathe. A bigger hospital could also buy medical supplies in bulk, making those purchases cheaper.

Stewart said he also made that suggestion to the board, independently of the consultants. He said leaders from Erlanger Health System, Memorial Hospital and Parkridge Health System had already approached him about working out a deal. They viewed a partnership with Hutcheson as a way to expand their services.

Those hospitals had already been increasing their North Georgia patient base for years.

Memorial was running an eight-physician family practice on Battlefield Parkway. Parkridge started operating Medical Associates of North Georgia and employing physicians in the region. Erlanger had launched South Family Medicine in Ringgold.

In 2001, according to the Tennessee Department of Health’s Joint Annual Reports, the three Chattanooga hospitals saw a combined 8,400 patients from Georgia. By 2011, that number was up to 12,600 — a 50 percent increase.

Other factors outside the control of Stewart or any other Hutcheson leader had also been weighing the hospital down at the time.

From October 2008 to March 2009, the unemployment rate in North Georgia rose significantly as a result of the recession.

In Catoosa County, the rate jumped from 5.3 percent to 9 percent. In Dade County, the rate jumped from 5.7 percent to 11.6 percent. In Walker County, the rate jumped from 6.1 percent to 14.2 percent.

That was an issue throughout the state. From 2008-10, the uninsured population in Georgia increased by about 300,000 people. The state government, meanwhile, provided a relatively low amount of Medicaid funding for small community hospitals.

From 2009-2011, Georgia provided about $3,900 in funding per Medicaid enrollee, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. That ranks Georgia 50th out of 51 states, including Washington, D.C.

The lack of funding from the Georgia budget directly impacts a hospital like Hutcheson, which has to treat Medicaid patients, regardless of how much money the state government provides. When a patient gets sicker than expected, the funding doesn’t change — a hospital like Hutcheson simply has to lose more money as it performs more operations to help the patient.

At Hutcheson, administrators also saw a 208 percent increase in charity care during Stewart’s time as CEO. Charity care procedures are medical operations done on uninsured patients whom the staff knows will never pay the hospital. Often, that is because the patients are not old enough to qualify for Medicare, not wealthy enough to afford their own insurance and not poor enough to receive coverage from the state-based Medicaid program.

In 2007, Hutcheson’s staff performed $3.12 million worth of charity care. By 2010, that annual figure had jumped to $9.61 million.

During those years, state lawmakers were actually debating whether to increase reimbursement rates for Medicaid to help hospitals like Hutcheson. In 2008, according to the governor’s proposed budget, Georgia planned to increase annual spending for the program by $35.7 million.

Because the federal government will also contribute Medicaid funding as the state increases spending, the budget projects that the boost would have actually meant an extra $100 million for the program.

Lawmakers, however, scrapped the plan when the recession hit.

“The proposed funding increase in 2009 was substantial,” said Tim Sweeney, deputy director for policy at the Georgia Budget and Policy Institute. “Had it originally been enacted, there would have been hundreds of millions in additional investment in Georgia’s health care system.”

In October 2010, with all those factors weighing against Hutcheson, a hospital committee reached for a life preserver. Thinking the hospital was $34.4 million in debt, the committee voted to form a partnership with Erlanger.

They made that choice instead of teaming with Memorial in part because Erlanger offered to loan Hutcheson $20 million.

Four months later, as leaders from Hutcheson and Erlanger hammered out the details of a management contract, Stewart resigned as CEO.

“I had fulfilled my obligation to the hospital in securing its future and its mission,” he said earlier this year.

But after Stewart’s departure, Hutcheson’s new team of managers discovered a problem: About $14 million of extra debt, according to a PowerPoint presentation to Erlanger executives years later.

As part of the Medicare program, Hutcheson received Periodic Interim Payments throughout the year. That is money that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services gives the hospital up front, in anticipation of how many procedures the hospital’s staff will perform on patients with insurance through CMS.

Several times a year, Hutcheson’s staff and a CMS representative were supposed to analyze the number of Medicare patients the hospital actually saw. Then, the two sides would settle the difference. Sometimes, CMS is supposed to give the hospital extra money. Other times, the hospital is supposed to give back some of that up-front payment.

But from 2007 through the beginning of 2012, according to Erlanger’s new management team at Hutcheson, nobody at Hutcheson or CMS analyzed those up-front payments. When the new team from Erlanger looked at the issue, they realized Hutcheson received $14 million more than they were supposed to.

Asked about that, Stewart said earlier this year that he relied on his chief financial officer to deal with those CMS payments.

How did the hospital end up with too much money, money the CEO’s successors would have to figure out how to pay back? Stewart said he does not know.