FORT OGLETHORPE — In November 2012, Hutcheson Medical Center’s chief financial officer examined a chart. He did not like what he saw.

He looked at the number of patients who visited the emergency room the previous day. Then, he looked at the number of patients who transferred from the emergency room to other parts of Hutcheson.

Farrell Hayes, a veteran hospital administrator, understood the key to success: Put more patients in the beds. More patients meant more money, and Hutcheson was desperate for money.

Visits to the emergency room alone would not help. Another company operated that department, and it took home those profits. Hutcheson’s leaders needed ER doctors to transfer patients to other parts of the hospital, where Hutcheson would cash in.

Looking at his chart on Nov. 30, 2012, Hayes saw that only 4.4 percent of the ER patients that month had been admitted to Hutcheson’s other sections.

“Who is working?” Hayes asked in an email to Scott Radeker, the hospital’s vice president of operations. “Census dropping. We need to fire their a**.”

Two days later, Hayes was still unhappy with the emergency room doctors.

“Scott,” he wrote on Dec. 2, “pitch a b**** fit.”

Privately, managers at the hospital expressed concern about Hayes’ style of leadership. He was confrontational during meetings. Often, multiple high-level employees told the Times Free Press, Hayes told them to fire any doctors or nurses who complained about their orders.

Hayes said he was merely joking. Still, some of the hospital’s directors told CEO Roger Forgey they were afraid Hayes’ comments put pressure on the medical staff to make certain decisions in pursuit of profits.

After a string of emails complaining about the admission rate from the emergency room to the rest of the hospital in late 2012 and early 2013, Radeker asked Forgey to address the problem.

“Be careful how you come across pushing ER admits,” Forgey wrote in an email to Hayes on Feb. 15, 2013. “We don’t want the (emergency department) doctors to admit anyone that does not meet criteria. We just want to be sure we are admitting the ones that do. We are on the same page but I don’t want that to be misconstrued.”

Nurses transport a wheelchair for a patient in the ER at Hutcheson Medical Center.

At the time, Forgey had just finished his first year as the head of Hutcheson. He and Hayes were friends dating back to the 1960s. They attended school and played baseball together.

Five decades later, Forgey says Hayes called him, asking if he needed an experienced financial officer. Hayes, for his part, says Forgey called him about the job. Either way, the two reunited in an attempt to right the ship.

When Forgey hired him as his new CFO, Hayes brought a track record of success managing hospitals. He first worked at Hutcheson in his 20s, rising to the CFO position for the first time at the age of 24. Five years later, in 1983, he left to become the vice president of a company managing psychiatric clinics.

Hayes managed hospitals through the 1980s and 1990s, retired early, became a competitive amateur golfer in Chattanooga and bought a golf course.

Now, back as Hutcheson’s CFO for the second time, Hayes drew the ire of some of the hospital’s directors. They saw him as an administrator from a bygone era, when less regulation marked the health care industry. They believed Hayes was trying to white-knuckle his way to success, squeezing money out of every available corner of the hospital.

In the fall of 2013, Forgey no longer saw any hope for the hospital to succeed. He asked to leave and recommended Hayes as the new interim CEO.

Some board members were disinterested. Though a well-respected accountant, the board saw Hayes as a poor public speaker who stumbled over his words while presenting monthly fiscal reports.

But given the hospital’s well-documented financial struggles and its open fighting with Erlanger Health System, the board members with reservations about Hayes didn’t think they had a better option. They didn’t believe Hutcheson would be appealing to a more-impressive CEO.

Said Hayes: “Nobody else (at Hutcheson) remotely was qualified.”

With Forgey’s departure, some medical staff members were worried about the direction of the hospital. Though Hutcheson continued to lose money with Erlanger in control, those losses trickled out at a slower rate than before. And Forgey’s presence on the halls of the hospital comforted some nurses and doctors who felt they finally had a leader who could relate to them.

“(Forgey) left,” said Patricia Kelley, a nurse, “and they brought in the circus.”

A patients' vitals are monitored in the ER. As Farrell Hayes took over as CEO, Hutcheson was on the verge of bankruptcy. He himself did not believe he was the best option to lead the hospital — just the best option available.

Privately, Hayes believed the CEO job was akin to that of a firefighter working a house that was too far gone. He just wanted to stop the damage from spreading.

“There was no chance to save the hospital,” he told the Times Free Press earlier this year.

When he took charge in November 2013, Hutcheson had been consistently losing money for 12 years. Hayes did not believe the hospital had enough money left to recover. He just wanted to find a company with deep pockets willing to buy Hutcheson and infuse the hospital with enough cash to keep the company afloat and the staff employed.

But the hospital came with baggage, and finding a prospective buyer proved more difficult than Hayes anticipated. Before anyone made a firm offer, administrators laid off employees in waves, month after month. Hayes himself even lost his job in December, when the bankruptcy trustee handling Hutcheson’s finances cut him loose.

And during Hayes’ search for a savior, a search that for two years felt fruitless, employees described to the Times Free Press a toxic work environment, where they believed the people in charge broke promises and failed to provide for the staff’s basic needs.

Administrators stopped paying hospital vendors. They stopped fixing leaks in the roof. They stopped paying doctors. They stopped paying employees’ health insurance. They pressured the hospital’s charity wing on how they should use their money.

Hayes accused doctors and other staffers of disloyalty. When some expressed concerns, he told them they could leave the hospital if they didn’t support his vision.

“We don’t have the luxury of time,” he wrote to senior managers in a Feb. 8, 2014, email. “Anything and anyone who is not totally committed to helping Hutcheson has to go now. Yes, 800 people might lose their jobs. But I will fight anyone to avoid that.”

For his part, Hayes said all of his actions were legal and ethical. He said he was dealt a bad hand and played the game as long as he could, saving employees’ jobs for two years.

He was the same hospital manager who made himself millions in the business in the 1980s and 1990s, but the game had changed. He said the community didn’t support the hospital enough, driving past Hutcheson to visit doctors in Chattanooga.

“I’ve been involved in a lot of turnarounds over the last 30 years,” Hayes told the Times Free Press in February. “Hutcheson was the hardest.”

Some upper level employees, however, don’t believe Hayes was really ever in charge. They think he was a pawn, carrying out orders for Walker County Attorney Don Oliver, though Oliver had no training as a hospital administrator.

Oliver had been influential within the hospital for years, demanding a board reorganization in 2011 and advising Walker County Sole Commissioner Bebe Heiskell not to support a bond issue to reduce the hospital’s annual debt payments in 2013.

Some of Hutcheson’s upper managers said Hayes even told them that Oliver was pulling the strings in the background, something Oliver and Hayes both deny.

“He was running the hospital,” said Mike Brady, who was in charge of physician relations at Hutcheson. “Farrell was running it day to day, but nothing got done without Don’s approval.”

A nurse wheels equipment in the ER. Though Farrell Hayes succeeded in operating a network of hospitals throughout the Southeast, some Hutcheson board members were pessimistic about his ability to lead their hospital.

When he returned to Hutcheson in 2012, Hayes had built a reputation as a financial guru in the health care industry.

Running a company called Healthcorp, Hayes had operated hospitals in Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Kentucky and Tennessee. Locally, he made his name managing North Park Hospital in Hixson, which he helped sell to Memorial Hospital in 1997 for $20 million. Memorial’s executives also agreed to absorb North Park’s $39 million of debt as part of the deal.

But when he took the reigns as Hutcheson’s CEO, many members of the staff said he cast a long shadow. Unlike Forgey, who walked the halls almost daily, Hayes almost never met with nurses and doctors face to face, multiple employees said.

And among those who did meet with him — upper level managers, mostly — Hayes appeared to be an authoritarian leader, unwilling to listen to outside opinions.

“He is truly old school,” Brady said. “‘If the physicians didn’t put enough people in the hospital, I’ll just fire them.’”

Linda Case, the director of the radiology department and a 40-year veteran at Hutcheson, said she was fired in March 2015 because she often raised concerns during meetings. She criticized Hayes for not paying back vendors. She said that on multiple occasions he promised to pay off the hospital’s debt to local suppliers, and Case would pass that message along.

Eventually, as the list of unpaid vendors grew, Case felt like a liar. She confronted Hayes during meetings.

“I was more vocal (than other directors),” Case said. “I questioned things. How are we doing this? We can’t tell people we are going to pay them when we aren’t.”

Regardless of whether Hayes laid Case off for criticizing him, other employees said they believed her version of events. They were shocked she lost her job after so many years at the hospital.

Said one former director: “Employees were scared to death to talk or complain about anything. You’ll be let go.”

Jerry Hines, a nurse at the hospital, said some of his co-workers didn’t know what Hayes actually looked like. Case said Hayes didn’t respond to emails and would skip scheduled meetings with employees.

Asked about criticisms from the medical staff, Hayes told the Times Free Press he did his best to make himself available to the workers. He held town hall meetings almost once a month. Outside of that, he simply didn’t have time to pander to every employee’s needs.

“Those disgruntled former employees: If that’s going to be the fodder for a newspaper article, write it,” he said, when asked about criticisms of his leadership skills. “But that’s way different than what the truth was. We had a lot of people working hard to save the hospital.”

Leonard Fant, a former Hutcheson CEO who continued to serve on the board of the hospital’s charity wing, said Hayes did his best in a tough situation. He doesn’t know if any executive could have kept the hospital running longer than Hayes did.

Another former director of the hospital also praised Hayes, saying the CEO’s heart was in the right place. Unfortunately for Hayes, the director said, he had to follow Forgey, whom many on the staff viewed as a dynamic and motivational leader.

“It might have been that Don (Oliver) didn’t let him communicate like he wanted to,” the director said. “Don plays things close to the vest. That might not have been all Farrell’s fault.”

A nurse walks down an empty hall inside Hutcheson. Along the hospital’s corridors, staff members often whispered the name of Walker County Attorney Don Oliver, believing he influenced Farrell Hayes’ decisions as CEO.

Among Hutcheson employees, Oliver’s influence was a mystery. They saw him in the hallways and heard rumors about the Walker County attorney, about how he was beginning to make many key decisions during Hutcheson meetings.

To Oliver, the speculation made no sense. Employees simply had too much time on their hands and were too interested in conspiracy theories. Oliver was the attorney for Walker County, and he was the attorney for the hospital’s board, and in both roles he was merely in the room to offer legal advice to the real decision makers.

“That’s ridiculous,” he said, when asked if he called any of the shots at Hutcheson during Hayes’ reign. “I never had an office at the hospital. I rarely visited the hospital, except for the board meetings.”

Hayes, too, denies that Oliver had any influence behind closed doors. He says he and the board members made all of the key decisions, and Oliver was there for support.

“I’m the world’s biggest fan of Don Oliver,” Hayes said. “I love Don Oliver. If Don Oliver’s going to stab you, it’s not going to be in the back. … The world needs more Don Olivers.”

Several senior staffers, however, said Hayes told them during meetings they needed to take certain actions to please Oliver.

Walker County wielded influence for a couple of reasons. First, the county guaranteed half of a $20 million loan from Erlanger in 2011, giving Walker County a seat at the table. Second, multiple board members and employees said that Oliver held sway over decisions made during board meetings, decisions that stretched beyond just legal advice. The board members appointed by Walker County in particular leaned on Oliver’s advice, the sources said.

“(Oliver) controls everything, man,” one board member said.

A former Hutcheson director, who supported Hayes, said she received “directives” from Oliver, telling her what the hospital needed to accomplish to stay afloat.

Case, the radiology director, and Brady, the head of physician relations, said they saw Oliver at the hospital almost every day. During one meeting, a senior staffer said Hayes told her the hospital needed to increase the admission rate from the emergency room to the rest of the hospital because Oliver wanted to see more patients coming in from the ER.

“Farrell said, ‘We’ve got to get these admissions up; Don Oliver will be telling me who to fire,’” the staffer said.

On Nov. 28, 2012, when Hayes was still the CFO under Forgey, he wrote in an email to the hospital’s management team that he had just had a conversation with Oliver and board Chairman Corky Jewell about the low admission rate from the emergency room. He said Oliver and Jewell were unhappy.

“They want to know why the new group is not getting it done,” Hayes wrote.

Two years later, in June 2014, Hayes told the hospital’s leaders that they needed to increase the number of patients inside the hospital to 40 by 7 a.m. the next day. Along with the hospital’s directors, he included Oliver on the email.

Hayes said he kept Oliver on the team’s group messages because he needed to stay in the loop on day-to-day developments as the hospital board’s attorney. Hayes also denied claims that Oliver made demands to himself or Hutcheson’s directors.

“I never heard that,” he said. “I never knew (Oliver) to send any emails or anything.”

Nevertheless, Oliver gained a reputation around the hallways of Hutcheson. Case said members of the staff referred to him as “that felon,” a reference to Oliver’s 1986 guilty plea for possession of amphetamine with intent to distribute.

RN student Ashley Flanagan stands in the ER.. Don Oliver told Hutcheson’s board that Walker County would loan the hospital $1 million if they hired Dr. Mike Aiken as a consultant. Aiken and Oliver were friends, and the board agreed to pay his company $30,000 per month.

One particular decision bolstered the idea among Hutcheson staffers that Oliver held sway at the hospital: The hiring of Dr. Mike Aiken, who was the majority owner of North Park while Hayes managed the hospital.

Hayes and Aiken had not worked together since selling North Park in 1997. But 17 years later, Hayes walked into a meeting in the Atlanta office of former Georgia Gov. Roy Barnes, who at the time was representing Hutcheson in a civil lawsuit against Erlanger.

Hayes saw the people he expected. There was Barnes. There was Oliver. And then, next to them, there was Aiken.

“I was kind of shocked,” Hayes said.

He thought Aiken had partnered with Regions Bank, to whom Hutcheson owed about $33 million, a court filing shows. He thought Aiken was coming in to purchase the hospital.

Then, Oliver explained the situation. He and Aiken had become friends years earlier, when Aiken needed help because of an issue he was having with the Walker County tax assessor. Oliver said it was a small misunderstanding, and he resolved the problem.

At any rate, the two men became friends. And when Oliver began representing with Hutcheson’s board, he called Aiken to help him understand why the hospital was in financial trouble.

Soon after that meeting at Barnes’ office, when the board gathered in May 2014, Oliver said Walker County would be willing to loan Hutcheson $1 million. But if the county was going to give more money to the hospital, he explained, the county’s leaders wanted to feel assured that Hutcheson was in the right hands.

Oliver urged the board to hire GB Health Management — a company Aiken had started two months earlier — to take over Hutcheson’s day-to-day operations. The board then hired Aiken’s company for $30,000 a month. In exchange, Walker County then promised Hutcheson $1 million from its general fund.

During a directors meeting, Hayes explained that Aiken held deep ties with local physicians and could bring more doctors to Hutcheson. But multiple upper-level staffers at Hutcheson said the deal with Aiken made no sense: The hospital signed away $30,000 every month to somebody barely involved in the actual operation.

“I never saw anything he did,” said one board member.

Several directors said that Aiken attended their meetings but rarely participated in conversations about how they should run the hospital.

“I never saw it,” Brady said. “I never saw any overt progress.”

“Mike was a ghost,” Radeker said.

“Everybody was like, ‘What does he do?,’” said another director. “‘What’s his role? Why’s he getting paid?’”

Hayes, meanwhile, is adamant that Aiken’s influence was crucial for Hutcheson. He said all decisions after May 2014 went through his former business partner.

“I love Mike Aiken,” he said. “He’s in the same category as Don Oliver. The world needs more Mike Aikens.”

Aiken did not return multiple calls seeking comment for this story.

An RN student prepares a bed in the ER. Though Hutcheson directors loathed Don Oliver and Dr. Mike Aiken, CEO Farrell Hayes defended both men. He said they were passionate about the hospital, that they made the hospital better.

Among staffers, Hayes’ most public battle was against EmCare, the company that provided ER doctors to Hutcheson. It was a struggle for the hospital’s greatest asset: its patients.

Because EmCare staffed the emergency department, the company took home the revenue from ER visits at Hutcheson. However, if the ER doctors decided a patient needed to be transferred to a specialist for any reason, Hutcheson would make money.

For example, if a patient visited the ER with chest pain, the EmCare doctors would transfer the patient to a cardiologist who practiced at Hutcheson. The cardiologist would then evaluate the patient and ask the hospital staff to run tests, and the patient would pay Hutcheson for those tests.

Even before Hayes became CEO, multiple upper level staffers told the Times Free Press, he believed the EmCare doctors were not admitting enough patients from the ER to the other parts of the hospital.

“Someone should review every single ER chart every day and highlight every ‘borderline’ patient who is not being admitted,” he wrote in an email to other staffers on Nov. 20, 2012. “On the ones who clearly should have been admitted, we need to ‘call the ER guys and the hospitalist on the carpet’ — and we need to do it every day.”

EmCare came to Hutcheson under Forgey, who wanted some new faces in the ER. He said the previous doctors were conditioned to transfer most patients to other hospitals. The number of specialists practicing at Hutcheson under former CEO Charles Stewart had dropped so low, transferring most patients had become a habit.

Forgey said EmCare was also able to bring in board-certified physicians, something the previous team lacked. He believed the new doctors would help increase the rates of admission from the ER to the rest of the hospital, eventually.

EmCare staffs 650 hospitals across the country, according to a company spokesman, including 50 in Alabama, Georgia and Tennessee. Hayes, however, was wary of the doctors.

According to multiple directors at the hospital, Hayes wondered aloud during management meetings whether the ER staff was the culprit for the hospital’s financial woes. He blamed Dr. Jon Allen, the ER’s medical director, and Dr. Patrick McDougal, the assistant medical director.

“Farrell was convinced the ER doctors were intentionally not admitting,” Radeker said.

Allen said he was accused of keeping patients out of Hutcheson on purpose, something that didn’t make sense to him.

“Where is the incentive for me to discharge somebody when I think they should be in the hospital?” he said. “That’s a significant liability on my part.”

Hayes and Oliver give slightly conflicting answers about why they did not approve of EmCare, though both insist they didn’t think the ER doctors made the right medical decisions.

Contrary to Radeker’s and Allen’s version of events, Hayes said he was never worried about admission numbers; he was only worried about patient safety.

“I wasn’t happy with the level of care,” Hayes said of the EmCare doctors. “It had nothing to do with admissions.”

Oliver, meanwhile, said the admission numbers did matter. He said they were a sign that the doctors were not making sound decisions. More patients should have been admitted into the hospital from the ER because more patients legitimately needed to see specialists.

When a reporter told him that Hayes was apparently not concerned about the admission rates, Oliver was taken aback: “I’m surprised that he would have said that.”

In fact, the hospital’s statistics show that the admission rate from the ER to the rest of the hospital plummeted before EmCare arrived at the hospital. The drop actually occurred during Stewart’s run as CEO from 2005-11, when many local doctors stopped practicing at Hutcheson.

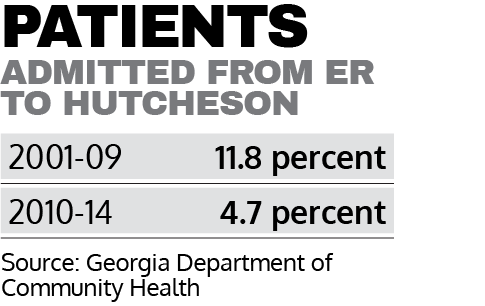

According to the Georgia Department of Community Health, the rate of ER patients admitted to other parts of the hospital from 2001-2009 was 11.8 percent. Then, in the middle of Stewart’s run as CEO, the admission rate dropped significantly. From 2010-2014, only 4.7 percent of ER patients were admitted.

The admission rate actually increased when EmCare came to Hutcheson. In 2012, the rate was 4.1 percent. In 2014, the rate was 5.9 percent.

But while the admission rate was higher with EmCare running the ER, Allen and McDougal said Hayes was still unhappy — despite what the CEO told the Times Free Press.

“There was a lot of finger-pointing and blaming that the volumes weren’t what they should be,” McDougal said.

He and Allen say Hayes’ concerns about patient care are disingenuous, that he pressured them to admit more patients even though many people who visited the ER didn’t have serious medical needs. Internal emails also suggest Hayes felt the ER needed to push more patients into the hospital.

“Chew Dr. Allen’s a** every day,” Hayes wrote to other staff members on April 7, 2013.

“Our job depends on you badgering the s**t out of the ER every day,” he wrote to another staffer on Sept. 24, 2013. “You and I have to lead the clueless.”

“Seriously,” he wrote on Oct. 1, 2014, “is it fun to have a job? Is it better than unemployment? … Whatever and whoever has to go, do it. I’ve had enough of this. And I’m ready to run over our lightweights McDougal & Allen. In the old days, neither would have lasted 1 week at North Park. And they may not last the next week at Hutcheson.”

Anthony Burba, a former prosecutor in the U.S. Department of Justice’s Medicare Fraud Strike Force, said Hayes’ emails are troubling.

“The conduct of this CEO is as bad as anything I’ve seen,” said Burba, who now represents health care organizations in the white collar crime practice group at Barnes and Thornburg law firm. “It certainly crosses an ethical border between the business management of a hospital and the ability of physicians to practice medicine without interference. … He certainly poses a compliance risk. I’ve seen cases brought against providers for less egregious evidence than this.”

Hayes also began asking employees to review the decisions of the ER doctors, looking at the charts of patients and deciding which ones should have been admitted to the hospital. First, Sandra Siniard, the director of Health Information Systems, began reviewing the charts.

Later, Hayes asked Stephanie Butcher to do the same job. Butcher was a clinical documentation specialist, meaning she trained the staff on how to use electronic medical records. She was not trained to evaluate a doctor’s decisions.

“Unleash the viper,” Hayes wrote to Radeker after appointing Butcher to the role.

Later, after Butcher reviewed the files and told Hayes she thought the ER doctors were making the right decisions, according to multiple senior staffers, Hayes brought in an outside group of case managers to begin looking at the charts. When those case managers also agreed the ER doctors were doing their job, Hayes stopped asking his staff to collect information from them.

“They were no longer interested in the data,” McDougal said.

A handmade sign labels the ER at Hutcheson. CEO Farrell Hayes fought a public battle with the ER doctors at Hutcheson. He says the doctors were making poor decisions and risking the health of patients.

Eventually, feeling uncomfortable about the situation, Radeker and Butcher reported Hayes’ treatment of the EmCare doctors to the hospital board. Radeker said Steve Ellis, a juvenile court judge and Walker County board appointee, was supposed to review their claims of abuse.

Radeker said he does not know how the board members felt about Hayes’ treatment of EmCare, only that nothing seemed to change once they were told what happened. Radeker resigned soon after, in October 2014. Butcher, meanwhile, was laid off a month later, when the hospital declared bankruptcy.

Ellis did not return multiple calls or an email seeking comment for this story.

In April 2015, Allen received an email from another doctor at another hospital. It was a forwarded message from ApolloMD, a physician’s group in Atlanta. The email said ApolloMD would soon staff the ER at Hutcheson.

That was news to Allen, who was the still the ER’s medical director. He said he called Kevin Hopkins, Hutcheson’s chief operating officer, asking if his team was being replaced. He said Hopkins told him he would forward the question to Hayes.

Allen did not hear back. About a month later, during a senior-level meeting, Allen said he asked Hayes directly whether his team was getting laid off. Hayes confirmed that he had partnered with ApolloMD.

Thirteen days later, the EmCare team was gone. Because the process for working at another hospital takes about three months, Allen said, the ER doctors could not work anywhere until September 2015.

Asked why he waited so long to tell the EmCare team that they were going to be out of work, Hayes said, “I don’t even know. There were a lot of things going on.”