FORT OGLETHORPE — During a meeting in Atlanta 4 1/2 years ago, an attorney pulled a hospital administrator into a hallway to make an offer.

Don Oliver, a lawyer representing Walker County as well as the Hospital Authority board that represents Hutcheson Medical Center, asked Roger Forgey to become the hospital’s CEO. Oliver feared the hospital was on a path toward bankruptcy, and he believed Forgey could steer Hutcheson toward the proper course.

Or at least, he was better than the other options.

“Not our first choice,” Oliver says now. “Not what we needed. But the best shot based on what (Erlanger Health System) was willing to do.”

When Oliver made that offer in December 2011, Hutcheson and Erlanger were eight months into a management agreement. Hutcheson’s leaders were $34.4 million in debt. Or, well, they thought they were. Soon, they realized they owed an extra $14 million to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

Leaders at both hospitals billed Erlanger as Hutcheson’s savior, the deep-pocketed heroes who could turn Hutcheson around. They brought a sense of security and re-branded the place: Erlanger at Hutcheson, they called it. In exchange, Erlanger got access to more patients in North Georgia, a battleground where Chattanooga’s other health care institutions — Memorial Hospital and Parkridge Medical Center — had also staked claims.

In addition to creating a plan for the future, helping Hutcheson recruit doctors and loaning Hutcheson $20 million, Erlanger officials promised to find the hospital the right CEO. But so far, Oliver and others were displeased with Hutcheson’s new leadership.

Debbie Reeves, Hutcheson’s former chief nursing officer, was serving as the interim CEO with help from Gregg Gentry, Erlanger’s chief human resources officer at the time.

In the seven months before the management agreement, Hutcheson lost $8.9 million. In the first seven months under new management, according to monthly board reports, Hutcheson lost $12.1 million.

And though hospital analysts say those financial reports can be misleading because payments take months to come in, Oliver and board members felt the hospital needed someone new in charge.

Forgey was a natural fit. He grew up 2 miles from the hospital and worked there as an orderly in the 1970s.

A 26-year employee at Erlanger, Forgey had helped launch the Chattanooga hospital’s trauma center and become its chief administrative officer. After the Erlanger-Hutcheson management agreement began, he spent hours of his free time at night consulting with the Hutcheson team, offering advice for how to make the hospital work.

“It was my hospital,” he said. “It was my home.”

To Oliver and other Hutcheson higher ups, Forgey became the face of Erlanger’s leadership. He met with them when they had problems, which is why he found himself in December 2011 in an Atlanta office with Oliver, board chairman Corky Jewell and hospital attorney Michelle Madison.

In addition to Oliver, Forgey said, Jewell pulled him aside during that meeting. Jewell told him that he would present his name to the board as the potential new head of the hospital, if Forgey was interested.

“I was flattered,” Forgey said. “I felt like I could help. … But I’m not sure you can save it.”

Forgey expected obstacles at Hutcheson. But he would later say his biggest challenge was appeasing the very lawyer who recruited him.

An empty room in Hutcheson. Fifteen years before Erlanger and Hutcheson negotiated a management agreement, Hutcheson’s leaders created a non-profit division of its operation, which Walker County Attorney Don Oliver described as a robot trying to destroy its creator.

For the next 22 months, Forgey became the head of a dysfunctional family, one that stayed together only because it seemed there was no other choice. When Erlanger and Hutcheson joined forces, they formed a partnership of competing egos from two hospitals, two county governments and multiple boards of directors.

To some Hutcheson leaders like Oliver, Erlanger represented a group of outsiders trying to take over a public hospital that had been treating North Georgia residents since 1953. At the same time, Hutcheson needed the $20 million loan that Erlanger offered.

Within Hutcheson, a fight among the members of two different boards also erupted. And within North Georgia politics, another battle ensued — this one between the leaders of Catoosa County and Walker County.

Catoosa County representatives believed their counterparts in Walker County were irrational, trying to kill the deal with Erlanger before it had a chance to work. Those in Walker County, meanwhile, thought the leaders of Catoosa County had grown too fond of Erlanger, favoring the Chattanooga hospital over the one in their own backyard.

For his part, Forgey quickly endeared himself to many members of Hutcheson’s staff. They saw him as transparent and personable — a far cry from how they viewed their previous CEO, Charles Stewart. Forgey walked the halls and visited every employee at their stations once a week.

A former nurse practitioner, Forgey connected with the staff and encouraged them to ask questions about the hospital’s finances.

In his own mind, unscientifically, he calculated that Hutcheson had a 95 percent chance of failing when he arrived. But, in a way, the challenge was fun.

“It would be hard for me to do any harm,” he said. “I could only help.”

Forgey and his administrators focused on recruiting doctors back to the hospital, many of whom left Hutcheson during Stewart’s years as CEO. The early results weren’t enough to make Hutcheson profitable again, but Forgey took pride in the improvements he saw.

In Fiscal Year 2011 — about half of which occurred with Stewart in charge, the other half with Gentry and Reeves — Hutcheson lost $23.8 million, unaudited financial reports show. (Auditors haven’t released official reports since 2010; the hospital has not paid what the auditors claim they are due.)

In 2012, with Forgey in charge for about eight months, the hospital lost $12.1 million. In 2013, Hutcheson lost $4 million.

During those two years, board reports show, the hospital had to spend a combined $20.2 million on outstanding debt payments, a holdover from previous administrations.

But Forgey’s long-term plan for Hutcheson never got off the ground, in part because of his precarious position as the leader of a hospital tethered to a second hospital and the elected leaders of Catoosa and Walker counties.

Though still an Erlanger employee, Forgey expressed frustration toward his co-workers in Chattanooga for not helping Hutcheson more. Jim Brexler, the Erlanger CEO who oversaw the partnership with Hutcheson, resigned seven months after the two sides reached a management agreement. Forgey wondered whether those still at Erlanger supported the partnership.

Walker County leaders wondered that, too. They didn’t think Hutcheson’s finances were improving fast enough. They didn’t trust anyone at Erlanger — Forgey included.

To most members of the management team that came to Hutcheson from Erlanger, there was no bigger opponent than Oliver, the man who helped convince Forgey to take the job.

“He had to serve two masters,” said Jerry Hines, a nurse at Hutcheson. “He had to keep Erlanger happy while he was having to do stuff for Hutcheson. He was set up to fail.”

Staff members work in Hutcheson’s emergency room. The hospital’s partnership with Erlanger created a complicated web of interests involving administrators at two hospitals, board members and local politicians.

The battles actually began in the fall of 2010 — before Forgey decided to become CEO, before Oliver or Jewell approached him about the job, before Erlanger and Hutcheson were officially partners.

But to understand the fight, one must examine its roots from the mid-1990s.

At the time, a board called the Hospital Authority of Catoosa, Dade and Walker Counties operated Hutcheson. The three counties’ elected leaders appointed the board members.

Seen as a form of government, the Hospital Authority had to play by certain rules. It was constrained by where it could practice medicine and with whom it could do business. For example, the Hospital Authority couldn’t partner with a for-profit company.

Then, in 1995, the hospital changed. Its leaders created a nonprofit division called Hutcheson Medical Center. The nonprofit didn’t have to play by the same rules as the Hospital Authority, and Hutcheson leaders believed the maneuver could make them more money.

Hutcheson Medical Center leased the building and the land from the Hospital Authority for $1 a year. The Hospital Authority and Hutcheson Medical Center each had their own boards, though the nonprofit called the shots. And unlike the Hospital Authority, elected officials didn’t suggest new members for the Hutcheson Medical Center board.

Instead, the Hutcheson Medical Center board members made their own selections to fill vacancies.

Walker County Sole Commissioner Bebe Heiskell and attorney Don Oliver did not care for this arrangement. Heiskell, who was elected in 2000, appointed Oliver to her team her first month in office.

A former state representative, Oliver brought Atlanta connections to the local government. He also brought a tainted reputation after pleading guilty in 1986 to possession of amphetamine with intent to distribute as part of an FBI-sting known as “Operation Sand Doom.”

In their first year in office, Heiskell and Oliver watched Hutcheson turn a profit of $2.2 million. Then, audits show, the hospital slipped, losing $43.5 million from 2001-2010.

Heiskell appointed Oliver to the Hospital Authority board. But he said he couldn’t do anything to right the ship.

“It wasn’t that (the Hospital Authority board) did nothing,” Oliver said. “We tried, and the HMC board said, ‘Y’all go jump in the lake. We’re not answerable to you.’”

In October 2010, with Hutcheson failing, the hospital’s leaders and Erlanger’s leaders agreed to negotiate a management deal. Erlanger would run Hutcheson and loan the hospital $20 million.

As those negotiations began, the Hospital Authority board voted to appoint Oliver as its attorney. Immediately, Oliver and Heiskell blamed the Hutcheson Medical Center board for the hospital’s financial ruin. Oliver said those board members lacked oversight. And before a deal with Erlanger could work, the counties needed to control the board again.

“It is the height of arrogance for the members of (the HMC board) to try to dictate to their creator, the Authority, how the Authority should handle this transition,” he wrote in an April 2011 email to attorneys for Catoosa County, Erlanger and Hutcheson. “It is so outrageous as to remind one of a horror movie where the robot turns on its creator and tries to kill off all the humans and take over the world.”

Some Hutcheson Medical Center board members say Oliver was disingenuous and had selective memory. They don’t recall Oliver or other Hospital Authority board members objecting to the hospital’s finances at the time. Neither board knew how bad the financial situation was until it was too late, they say, because administrators in the 2000s were not forthcoming.

Members of the Hutcheson Medical Center board also wondered if Oliver’s vendetta against them was personal for something they did in March 2006. When Stewart was the CEO, the hospital filed a $420,000 demand in Walker County Superior Court, saying Heiskell was not paying the hospital all the money the county owed for procedures that the Hutcheson staff performed on county inmates.

Paul Chambers, an HMC board member, said he met with Heiskell to try to convince her to make the payments.

“The commissioner told me that if someone would bring the exact bills, she would write a check,” Chambers said. “Well, I called the hospital and had a courier bring me those bills. I presented them to her. She said that she would write me a check. The checks were never forthcoming.”

The county and the hospital reached a settlement later that year.

“It was one of the stupidest things (Stewart) could have done,” Oliver said.

He said the payment was only a couple of thousand dollars, though after receiving a public records request earlier this year, Oliver said the county no longer has a record of the settlement’s exact amount.

While Hutcheson and Erlanger continued to negotiate, county officials and members of the two boards held contentious meetings. Multiple sources in the room say Heiskell berated HMC Board Chairwoman Martha Attaway, claiming Attaway was to blame for the hospital’s failures.

Heiskell did not return multiple calls for this story, and Attaway declined to comment. But others in the room say the negotiations were confrontational almost from the beginning.

“I carried a letter of resignation in my pocket to all those meetings,” Chambers said. “I was ready. But I felt the best way to salvage the hospital was to enter that partnership with Erlanger.”

In the end, the sides agreed to reform the hospital’s structure. Hutcheson would have nine board members — two from Dade County, three from Catoosa County and four from Walker County. The counties’ commissioners would make suggestions for who would represent them, subject to board approval.

As the management agreement with Erlanger was almost finished, Oliver and Heiskell also demanded that all the board members resign, allowing the counties to start over with fresh appointments.

Within the hospital, some staff members viewed the deal as a power play orchestrated by Heiskell and Oliver.

“Don seized this moment to take control,” said one former upper-level manager at the hospital.

Said a board member who agreed to resign: “Nobody dreamed that it would be a takeover. They just thought that they were agreeing to the management agreement (with Erlanger). They were going to save the hospital, and everything would work out fine. But as the years went by, Bebe’s board members were making the decisions.”

A second fight erupted during the Erlanger-Hutcheson negotiations, this one between the Chattanooga hospital and Walker County’s leaders.

Hutcheson board members approved of the deal with Erlanger for three main reasons. Erlanger agreed to loan Hutcheson $20 million. Erlanger was publicly owned, like Hutcheson. And, like Hutcheson, Erlanger performed a significant amount of charity care — $107 million worth at its hospitals the year the two sides were negotiating.

Still, Oliver didn’t trust the folks in Chattanooga.

“(Walker County) never wanted Erlanger to start with,” Oliver said. “We said from day one, ‘This is a scam. Erlanger is going in here to run this place in the ground and shut us down.’”

Oliver and Heiskell had power in the negotiations because they agreed to guarantee half of Erlanger’s $20 million loan with taxpayer money. If Hutcheson didn’t have the funds to repay Erlanger in the future, Walker would be on the hook for about $10 million. Catoosa County would pay the other half. (The enforcement of that guarantee from Walker County is still being debated in federal court.)

In the weeks leading up to the final deal between the hospitals in 2011, Walker County officials tried to derail the negotiations. On March 18, Heiskell announced she would not approve the agreement unless Erlanger officials promised to stay at Hutcheson for 20 years.

On March 24, Oliver said Hutcheson should first issue a bond to restructure all of its debt before reaching a deal with Erlanger, even though another attorney representing Hutcheson said that would take too long — Hutcheson would run out of money and shut down before such a bond issue could go through.

On March 26, Heiskell said Hutcheson should not sign off on the deal until it got its own loan rather than the $20 million from Erlanger. She said Hutcheson’s board could find a loan with a lower interest rate than the one Erlanger offered.

On April 1, at Oliver’s invitation, a health care company from Naples, Fla., pitched its own management agreement to the Hutcheson board. The next day, Oliver announced that officials from Parkridge Health System and Memorial Hospital were going to offer their own management agreements, even though Hutcheson had already chosen Erlanger over Memorial five months earlier.

Some of those at the table during the negotiations between Erlanger and Hutcheson said Oliver took a stance closer to that of a war general than an attorney.

“He is a bright, bright man,” Forgey said. “And he’s a lot of fun to be around. But it feels like he just wants to fight for the sake of fighting. I don’t understand it.”

Internally, Forgey said, Erlanger leaders debated whether to walk away from the deal, worried about having to work with Oliver going forward. But Brexler was passionate about the partnership. He felt it could be mutually beneficial, that what happened inside the Fort Oglethorpe hospital directly impacted Erlanger.

Those patients would need treatment, one way or the other. If Hutcheson closed, Brexler figured, they would flood the halls of Erlanger. It would be too crowded. He preferred keeping Hutcheson as a satellite operation for Erlanger, treating the north Georgia patients in north Georgia.

“For the most part,” Brexler told the Times Free Press earlier this year, “Erlanger would have taken on the full brunt of the responsibilities of indigent care in the region. We are going to be accountable in the area anyway. Hutcheson is just 10 miles away.”

On April 6, Hutcheson employees lined the hallways, urging members of the Hospital Authority board to sign off on the agreement with Erlanger. Some scrawled messages on posters, like they were attending a football game.

“SAVE HUTCHESON,” read one sign

“DO THE RIGHT THING,” read another.

“Save my mommy’s job,” read a third, held in the hands of a nurse’s baby.

The Hospital Authority voted to approve the deal. When the board members exited the room, the staff applauded.

“It gave us hope,” said Linda Case, the director of Hutcheson’s radiology department.

Heiskell signed off on the management agreement, figuring that resisting the deal any further would have been a public relations nightmare. She believed the hospital would, in fact, shut down without some sort of partnership. She has since said residents sent her death threats for resisting the deal.

The elected leaders in Catoosa and Dade counties, meanwhile, were publicly supporting the agreement, putting more pressure on Heiskell.

Oliver was not happy. He saw outsiders taking control. Outsiders he didn’t trust. Outsiders who didn’t guarantee they would save the hospital. Outsiders who, some day in the future, would be asking for their $20 million back.

“I either wanted to alter the deal or kill it,” he said. “It was a terrible deal.”

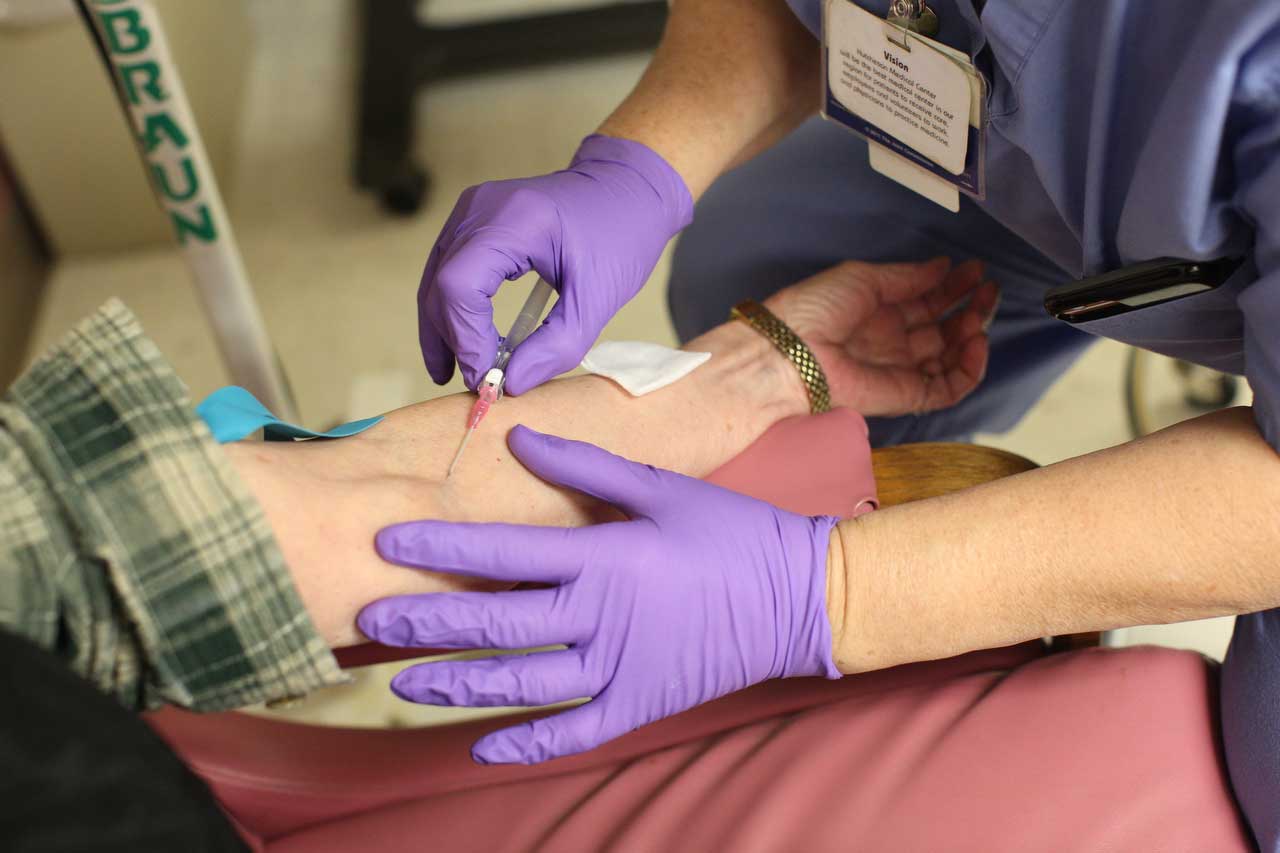

A patient receives an IV at Hutcheson. When he took over in 2012, Hutcheson CEO Roger Forgey said the hospital lacked enough doctors to turn a profit.

Roger Forgey took over Hutcheson in February 2012.

“It was the worst situation I’ve seen in my career,” he said. “We didn’t have any doctors. We didn’t have any patients. We didn’t have any hope.”

In the last years before Erlanger took over Hutcheson, the number of specialists practicing at Hutcheson had dropped 68 percent — from 198 in 2007 to 64 in 2010. Meanwhile, according to Erlanger’s calculation, Hutcheson owed $11 million to vendors, many of them local companies with whom Hutcheson’s officials needed to maintain strong relationships.

A couple of months after arriving, Forgey said he and Chief Financial Officer Farrell Hayes realized the hospital had received $14 million more in Medicare payments than the hospital should have during Stewart’s years as CEO. Hutcheson needed to pay the money back, and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid charged them an interest rate of about 11 percent, according to an Erlanger document.

Also, for six months, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid stopped giving Hutcheson any payments for work on Medicare patients.

“For a hospital,” Forgey said, “that’s generally unsurvivable.”

Despite all those issues, Forgey quickly won over many staff members, who said his background as a nurse practitioner helped him connect. They trusted him, and he was an open communicator, answering emails from employees late into the night. He visited the hospital’s different departments for at least five minutes every week, just to see if any of the employees had questions.

“He had his heart in the right place,” said Case, the radiology department director.

Added Mike Brady, who was in charge of physician relations under Forgey: “Roger was a motivator.”

At the same time, several upper level Hutcheson sources said, Forgey found himself pitted against Oliver, who remained the hospital board’s attorney after the shakeup during the Erlanger negotiations. In monthly board meetings, according to multiple sources inside the room, Oliver interrupted conversations and offered his opinion about how the hospital should run.

Asked about this, Oliver said he merely was at those meetings as the board’s attorney; he only offered legal opinions when asked.

Forgey described Oliver as a smart, well-connected politician. He said Oliver “worked the room,” talking to as many board members as possible before and after meetings. To Forgey, it seemed like some of those board members would then change their minds about decisions they had made during those same meetings.

Those board members who weren’t swayed by Oliver expressed frustration.

“My perception was that the board had issues with Don,” Forgey said. “I wasn’t the only one who had concerns.”

Still, Forgey and other senior managers insist the hospital was slowly improving. They paid off debts to local vendors, which Forgey said is where a large chunk of Erlanger’s $20 million loan went — $11 million of which had already been spent before Forgey arrived 10 months into the management agreement.

Also, some doctors who had abandoned Hutcheson under the previous regime returned to the hospital. According to a presentation Forgey made to his colleagues at Erlanger in August 2013, 33 doctors started practicing at Hutcheson who were not there when the management agreement began.

This included areas of medicine in which Hutcheson had no specialists as of April 2011: cardiologists, orthopedists, gastroenterologists and pulmonologists. The new team at Hutcheson also brought in the Dalton Surgical Group to provide on-call coverage, something the hospital did not have at the time.

Brady and Forgey played themselves against Stewart, whom some doctors in the community refused to work with, saying his ego was overwhelming. Eventually, Brady said, local primary care physicians brought their patients back to Hutcheson.

“I came in and treated them like gods again,” Brady said of the doctors. “The fact that (Charles Stewart) was so awful, in their opinion, made it easier for me. A lot of it had to do with Roger. He was a new CEO, very physician-friendly.”

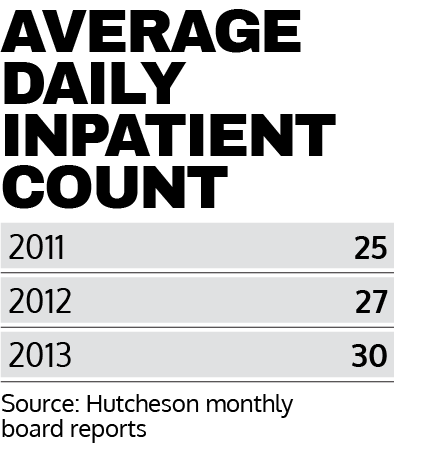

The average daily inpatient census at Hutcheson increased under Forgey, though only slightly. In 2011, about 25 patients stayed in the hospital every night. In 2012, the figure was 27. In 2013, the figure was 30.

Forgey argues that the biggest growth was actually in outpatients — those who receive medical treatment without being admitted into the hospital. Among other things, that could be for a clinic visit or a surgery during the daytime.

Hutcheson’s monthly board reports do not measure that growth. But according to his report to Erlanger, Forgey said the total number of admissions (inpatient and outpatient) increased under his watch. From February 2011-February 2012, he said, the hospital admitted 6,064 patients. From February 2012-February 2013, the hospital admitted 6,701 patients — an 11 percent increase.

Still, in the years since Forgey’s run as CEO, Oliver and others at Hutcheson have argued that Erlanger never wanted Hutcheson to succeed, that the Chattanooga hospital’s administrators executed a hostile takeover to choke the life out of Hutcheson.

Their main argument was about doctors, or the lack thereof.

Critics of Erlanger recall a meeting in October 2010, a year and a half before Forgey’s arrival. During a meeting between Hutcheson officials and Erlanger officials, according to multiple sources in the room with loyalties to both hospitals, Brexler said he would bring eight-15 new doctors to Hutcheson.

Bill Craig, a Hutcheson board member from 2003-2011, said Brexler floated the same number of doctors to him when they met at a party later that year.

“They promised this, that and the other,” Craig said. “It sounded real good to me.”

But Erlanger only paid for one doctor, a cardiologist. For his part, Brexler now denies promising to pay for more physicians. He said he merely told the Hutcheson team that Erlanger would help recruit doctors.

Brexler’s presentation does not mention paying for any doctors, just that Erlanger would help Hutcheson rebuild the hospital’s physician base after so many doctors left under Stewart. Likewise, the actual contract between Erlanger and Hutcheson does not mention Erlanger paying for doctors.

A member of Hutcheson’s staff draws blood from a patient. With a team of administrators dedicated to recruiting doctors back to Hutcheson, and “treating them like Gods again,” Hutcheson began to see a slow increase in patients.

The contract says Erlanger will invest in “community-based physicians’ practices.” But the language is vague, leaving out details about how much Erlanger would spend or what investing in those practices even means.

“What they wanted and what we wished for was not what we believed we could do,” said Brexler, now the CEO of Doylestown Health in Pennsylvania. “It was going to take time to pull that organization up.”

Last year, during an appearance on local cable access TV, Heiskell said she was skeptical of Erlanger at the time of the negotiations because Brexler promised to pay for new doctors — but the contract did not mention that.

“They didn’t want to put in writing the things they promised us,” she said. “I thought they should.”

Though Forgey is adamant his staff worked as hard as they could to save Hutcheson, even he admits he was frustrated with Erlanger’s leaders at the time. Internal emails show Forgey begged them to provide more help.

“Please guys,” he wrote in May 2012. “I’m dying here. Without the ability to recruit there is no chance for survival.”

“I am in fact living off the morsels off your table,” he wrote in fall 2013. “This is not going to work and I cannot be expected to work like this. I look like a liar.”

Said Catoosa County Attorney Clifton “Skip” Patty, a supporter of Erlanger: “There were some things that they can be criticized for; there’s no doubt about that. If you examine what Mr. Forgey was asking for and what he got from Erlanger, he didn’t get everything.”

Added Leonard Fant, a former Hutcheson CEO who served on the hospital’s foundation board at the time: “Erlanger had the power to fill in those gaps in the medical staff. They didn’t do it.”

The entrance to a room in the Hutcheson ER. Even though tension persisted between leaders from Hutcheson and Erlanger, the two sides tried to hammer out a long-term deal. Under the agreement, Erlanger would have leased the hospital for at least a decade. However, the lease agreement fell through.

Though relations between the two hospitals remained tense, in 2013 representatives from both sides discussed Erlanger making a more long-term commitment.

Hayes, the Hutcheson CFO, announced in January 2013 that the hospital was on track to make a $4 million profit for the fiscal year. That did not turn out to be true: Hutcheson ultimately lost $4 million, according to a financial report to its board. But Forgey and Hayes remained optimistic about the hospital’s performance.

To Forgey, the loss was not devastating because his team was forced to run uphill. The decisions of previous administrations weighed heavily against them. In Fiscal Year 2013 alone, monthly board reports show, the hospital had to make $10 million worth of debt payments.

Without the old debt, Forgey figured, his staff would have actually turned a profit. And he had a plan to account for this problem: Ask the local governments to bond out the debt.

If Catoosa and Walker counties worked together and secured a long-term loan on behalf of Hutcheson (which Hutcheson administrators said they would pay off), the hospital’s debt payments every year would only be about $3 million.

They would have to make these annual payments for about 30 years, but Forgey said the hospital’s leaders would be able to keep their heads above water, assuming Hutcheson performed liked it did in 2013.

In April of that year, Hutcheson publicly announced it was looking for a long-term partner to lease the hospital. It wasn’t shy about praising Forgey during its pursuit.

“We have a management team that is good enough to run the hospital and should be on a level playing field,” Jewell told the Times Free Press at the time. “Up until now, the cards have been stacked against us.”

In June 2013, leaders from Erlanger, Catoosa County, Dade County and Walker County agreed to formalize a deal that would allow Erlanger to lease Hutcheson for 10 years. When the Erlanger board signed off on this agreement during a monthly meeting, a team of Hutcheson representatives cheered.

Two months later, however, the deal died. Kevin Spiegel — who had replaced Brexler as Erlanger’s CEO — said at the time the terms of the agreement changed when his team did its “due diligence” in examining Hutcheson. He did not provide specifics, though he said Hutcheson would need to grow its business by 10 percent “in a very short turnaround” to make money.

According to a December 2013 Times Free Press story, Erlanger’s administrators offered to lease Hutcheson for $2.5 million per year for 10 years. County officials, however, wanted Erlanger to pay $4.4 million.

With the deal dead, Hutcheson’s board severed its ties with Erlanger, ending the management agreement in August 2013.

Jewell told the Times Free Press that the agreement with Erlanger failed to meet “the expectations of Hutcheson’s Board of Directors or the leaders of Walker, Dade and Catoosa counties. A continuation of the agreement would not add value to the hospital.”

One senior director who came from Erlanger with Forgey said the Chattanooga hospital’s leaders didn’t see Hutcheson as an asset, the way Brexler did: “None of them (at Erlanger) had the appetite for Hutcheson. I don’t think any of them had the vision that Brexler had. There was no support from the leadership.”

Asked about that, Spiegel did not return an email seeking comment through a spokesperson.

Even as the deal died with Erlanger, Forgey remained in charge at Hutcheson, fighting one last battle.

He petitioned the counties to still issue the bond deal, saying a long-term loan was the only way to make Hutcheson profitable again. Otherwise, he said, the hospital would have to file for bankruptcy.

When he first took over in 2012, he explained to the board that the $20 million loan from Erlanger was only good enough to pay off some of Hutcheson’s debt. If he could prove that Hutcheson could stay afloat after that, he said, the bond issue would be worthwhile.

Then, senior managers hoped, the hospital could look into constructing a new building on Battlefield Parkway. The current hospital sits off old LaFayette Road in Fort Oglethorpe, a location that made sense in the 1950s.

With time, however, the North Georgia population has drifted east, closer to Interstate 75. If the hospital was near the highway, several directors and board members hoped, more people would visit Hutcheson.

Toward the end of 2012, leaders at Hutcheson and the attorneys for Catoosa and Walker counties began to discuss issuing the bond.

Chad Young, a lawyer representing Catoosa County, said he spent months hammering out the details of a $60 million bond. He said each county would guarantee half of the loan. He thought Catoosa and Walker leaders agreed that was the best course of action

Catoosa County called a special meeting in September 2013. They planned to issue a “bond anticipation note” for $35 million. That would be a promise to a financial company: Give us $35 million and we’ll pay you back in a couple of months, once we have issued a second, $60 million bond.

For weeks, Young said, he and leaders from Walker County talked about that plan. Then, days before the meeting, Catoosa County officials got a call from someone at Heiskell’s office, telling them Walker County would no longer support the deal.

“We were sort of surprised,” said Patty, another attorney for Catoosa County. “We really thought that was going to go forward.”

The Catoosa County Commission still held its meeting. It voted to issue the $35 million bond, assuming Walker County would guarantee half of it.

Heiskell, the Walker County commissioner, told the Times Free Press soon after: “I will not do it. I will not put Walker County taxpayers unnecessarily at risk.”

A week later, Catoosa County’s leaders pulled their offer, unwilling to guarantee the full $35 million by themselves.

Forgey and other senior managers said they believed Walker County was going to help them, assuming they could keep Hutcheson running smoothly. They said Oliver even told them that during meetings. Now, they felt betrayed.

Oliver, meanwhile, said Forgey’s team did not properly view their own time at the helm.

They were never as successful as they thought, Oliver said. Had they proven that they would be able to make Hutcheson consistently profitable, he would have supported the bond issue. That, he said, was the deal all along.

Oliver said he gave Forgey’s team benchmarks to hit to prove they would be able to pay the loan every year. He said they never came through, though he doesn’t remember what the specific benchmarks were.

“All we needed to do,” he said, “was see those payments could be made. Those benchmarks were never met. We didn’t have sufficient evidence.”

Oliver was wary of guaranteeing a loan that could have cost Walker County an additional $30 million if Hutcheson couldn’t pay back the massive bond. The county simply couldn’t afford such a loss, not after already guaranteeing that $10 million from the Erlanger loan in 2011.

Forgey then watched the county governments pour smaller payments into Hutcheson. After Catoosa and Walker counties agreed to guarantee a $3.5 million loan for the hospital in June 2013, Walker County guaranteed another $1 million loan in November 2013. In May 2014, the county issued the hospital a $1 million promissory note from its general fund.

Forgey said Walker County’s decision marked the death of his time as CEO. He believed the hospital would fail without a long-term loan.

“It was as if Walker County thought that with enough $3-$5 million payments, we were going to come out like a phoenix and be OK,” he said. “We were never going to be OK.”