FORT OGLETHORPE — In November 2014, Hutcheson Medical Center’s leaders admitted their community could no longer support a public hospital.

Or they simply hit the the pause button, in one last effort to survive.

It depends on who you ask.

The hospital filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy on Nov. 20, 2014. This was not necessarily a death sentence. Though they held about $80 million in liabilities at the time, Hutcheson would not have to make debt payments so long as the hospital was protected by bankruptcy court.

CEO Farrell Hayes now says this was part of his larger plan: Sell the hospital. Hutcheson was too far gone, he figured. If he didn’t have to make debt payments, he could keep his head above water, keep the doors open, give a potential buyer a chance to take over.

Walker County Attorney Don Oliver, meanwhile, believed Hutcheson could still survive. The hospital had to file for bankruptcy, he said, to keep lawyers from Erlanger Health System away.

With Hutcheson owing Erlanger $20 million from a 2011 loan, and with Hutcheson’s board promising to give its campus to Erlanger should the hospital not be able to pay back that debt, Erlanger moved to foreclose in the fall of 2014. If nothing else, the bankruptcy filing stopped Erlanger from executing the plan.

Ultimately, Oliver said, the legal maneuver did not work. Hutcheson couldn’t stay afloat after its filing. Oliver blames Hutcheson’s collapse on Erlanger, saying its effort to foreclose on the hospital was heartless.

Oliver wonders what would have happened to Hutcheson otherwise.

“They were doing a good job of rebuilding the physician base and managing the assets,” he said of Hayes’ team, which took over in November 2013.

Under Oliver’s leadership, Walker County had blocked an effort in 2013 to bond out Hutcheson’s debt when Roger Forgey was the CEO. This bond would have reduced the hospital’s annual debt payments, making management of the place easier. But with Forgey gone and Hayes in charge, Oliver said the county had been thinking about issuing that bond.

He felt more confident with Hayes, believing Hayes had a firmer grasp on the hospital’s finances. Then, Hutcheson filed for bankruptcy.

From December 2014 through November 2015, monthly financial reports show, Hutcheson lost $7.2 million.

The number of patients at the hospital also declined. In December 2014, an average of 31 people were in inpatient services. By September 2015, the last month for which that data was available, the number was down to 16.

But some on staff say the official figures don’t tell the full story.

Janet Benson, a nurse at Hutcheson, sometimes spent entire days seeing no more than 10 patients. Case and other veteran staffers would sit around during lunches, reminiscing on the days when the hospital was too busy for 30-minute breaks.

Rumors swept through the empty halls as employees wondered when the hospital would close.

“It was very stressful,” said Angela Polizzi, a pre-certification specialist. “You just didn’t know day to day if you were going to walk in and have a job, or if you would pull up and the doors be locked.”

Added another nurse: “It’s almost like you’re watching something die, and you can’t do anything.”

On Thursdays, when administrators distributed paychecks, some employees drove together to Regions Bank, hoping to deposit the money as soon as possible, fearing the checks would bounce.

In early October, a letter from the hospital’s upper management greeted the staff. They would get their paychecks on the following Thursday as usual, the letter read. But don’t deposit the checks until the next day.

Then, Benson said, the administrators changed their minds: They would not be giving the checks until Friday — but employees could cash them whenever they wanted.

“I have very, very little respect for (Hayes) as a leader,” said Patricia Kelley, a nurse. “He never came around to do rounds in the ER, to see people. Every time he had a town hall meeting, it was like, ‘I pray for you guys and I worry about you.’ … It was total BS.”

Employees also watched parts of an already old building begin to fall further into disrepair.

By the time Hayes took over, the plumbing and electrical systems needed to be replaced, said Greg Crosslin, the hospital’s director of engineering and security. Other pieces of the building began to crumble, too. Sections of the roof leaked, Crosslin said, and administrators told him they didn’t have money to fix the problem.

“We tried to repair the roofs as best we could,” Crosslin said. “We didn’t want mold in the building. We were just trying to prevent any water from coming in.”

Scott Lewis, a paramedic, said employees began swapping out soggy ceiling tiles to keep the floors dry. Some of the elevators started to break, too, he said.

The medical staff also ran low on supplies. Benson said the Dinamap machine for measuring a patient’s blood pressure lost the ability to read temperature or oxidation levels. Nobody fixed the problem.

She said at one point the hospital’s CT and MRI machines were not functioning. Her boss told her not to print anything unnecessary because the hospital’s paper supply was running low.

Kelley said administrators stopped replacing their portable oximeters, a device used to measure a patient’s oxygen saturation. Instead, she said, the nurses bought them with their own money, knowing hospital executives would not reimburse them.

Radiology Department Director Linda Case said that when a cancer patient’s bloodstream was blocked with a clot or a mass of bacteria or an air bubble, the medical staff would use a special catheter. At some points in 2015, the staff worked on a cancer patient with only one of those catheters left.

“God forbid the wire flip out,” Case said. “You need extra supplies.”

And when Hutcheson did have supplies, multiple directors said, vendors didn’t get paid. Case said she tried to track down Hayes, demanding the hospital pay back local companies. The hospital had done business with them for years.

“He never returned your email,” she said. “If you set up a meeting to talk to him about it, you might catch him: ‘Oh yeah. Oh yeah. We’ll get it done.’ It didn’t happen.”

Crosslin said that Hayes also promised him they would pay the local vendors whom Crosslin had worked with since joining Hutcheson more than 25 years earlier. Receiving promises from Hayes, Crosslin said he passed the information on to those vendors.

Later, when the hospital filed for bankruptcy, Crosslin learned Hutcheson was not going to pay any of his contacts.

“I got a lot of nasty text messages from some of the vendors,” he said.

Physicians, too, stopped getting paid.

Dr. Chris Moore, the hospital’s chief medical officer at the time, said Hutcheson occasionally didn’t have a hospitalist on call. These are the doctors who see patients in between specialists, serving as a go-between to make sure the patient is OK.

Moore said he would call doctors in the middle of the night, begging them to come in.

Brady, the director of physician relations, said the hospital fell eight months behind on paying some of its physicians. One week, he was promised those doctors would get paid by Friday. He passed the message on to the doctors.

Friday came. Brady arrived at Hutcheson and found those same doctors waiting in his office. COO Kevin Hopkins told Brady they weren’t actually going to pay those doctors that day. One week later, Brady quit.

“That was the last straw for me,” he said.

A room in the ER sits abandoned. In the months after Hutcheson filed for bankruptcy, some nurses said they ran low on supplies, that they had to buy necessary devices with their own money.

Some hospital employees said administrators were also not forthcoming about issues threatening their paychecks — and their lives.

Annette Brack, a respiratory therapist, visited a dermatologist when she was concerned about a rash in January 2015. While there, the dermatologist performed a full-body exam and found a small, dark spot in between her toes on her left foot. It looked like a bruise.

The dermatologist removed some of the skin and tested it. The sample came back positive for melanoma. Brack visited another doctor who removed a larger portion of her skin. The cancer was rapidly growing, and atypical.

The doctor wasn’t sure what specific type of cancer Brack had. Samples were sent to researchers at the University of Notre Dame and Brigham Young University, but they didn’t find a clear answer.

A doctor removed another ring of skin, about three-fourths of an inch deep into Brack’s foot. The doctor thought it could be spreading throughout her body, and so Brack promised to visit the Cancer Institute at Northside Hospital in Atlanta.

That’s when she found out Hutcheson was not paying her health care claims anymore. Looking at her insurance, she said the staff at the Cancer Institute told her she would have to pay $5,000 up front before a visit.

Hutcheson is self-insured, meaning the hospital takes money from employees’ paychecks and gives it to Managed Care of America, a third-party company. MCA then distributes the money when an employee has a health care claim.

But Brack said an MCA representative told her Hutcheson stopped giving them money, even though hospital administrators were still withdrawing deposits from their paychecks. (Brack said $160 were deducted from her checks.)

Without coverage, Brack decided she couldn’t afford to visit the Cancer Institute. She stopped visiting doctors in March 2015. Brack provided the Times Free Press with a stack of medical bills showing that she owed at least $23,000.

After getting laid off in October, Brack said she found a new job. The job came with a new insurance plan, but that didn’t kick in until February.

In the meantime, her credit score tanked. She said she couldn’t get a loan when she bought a car last year. She said administrators at Hutcheson wouldn’t give her a straight answer about why her claims weren’t covered.

“They lied to us all,” she said. “It became personal because they stole your money. That’s how you feel about it. You’re paying for a service, and it’s gone. And nobody can tell you the truth about what happened to your money.”

Several Hutcheson employees reported similar issues to the U.S. Department of Labor, which has launched an investigation into Hutcheson. According to a Nov. 23 filing in U.S. Bankruptcy Court, the Department of Labor has found that Hutcheson owed employees at least $2.2 million for medical claims.

“They took our money as employees to provide health insurance,” Brady said. “They didn’t provide it. How the hell do you get away with that?”

Hayes said the company paid claims — they were just behind because the hospital was short on cash. When the hospital filed for bankruptcy, he said, they legally had to split their debts between those accrued before bankruptcy and those accrued after the filing.

He said his lawyers told him the hospital could not pay any debts from before bankruptcy. And because the hospital viewed the unpaid health insurance claims as debts, they thought they were not allowed to make those payments.

“Three or four months went by,” Hayes said. “We didn’t realize that health claims didn’t apply (to those debt payment rules).”

Rob Williamson, one of Hutcheson’s bankruptcy lawyers, said he could not speak about any specific advice he gave Hayes because that is protected by attorney-client privilege. But he said the health care claims issue was not about pre-petition and post-petition debts. It was about cash flow — plain and simple.

The hospital didn’t have enough money to pay insurance claims, and it fell behind on covering employees. Williamson said Hutcheson was still paying the insurance company. The money just came in late, and some employees were turned over to collection agencies.

According to the hospital’s December financial filing in bankruptcy court, Hutcheson made $3.6 million worth of insurance payments from November 2014 through the end of 2015.

Even though employees made contributions to their insurance plans (like those $160 deductions from Brack’s check), Williamson said, the hospital still didn’t have enough money to make their contributions to the plan.

“We’re going to settle as many of those claims as we can before the case is closed,” Williamson said earlier this year. “It’s on our radar.”

According to another filing in bankruptcy court in November, the Department of Labor is also investigating whether Hutcheson failed to supply employees with their retirement benefits.

Meanwhile, Hayes looked to the Hutcheson Health Foundation to kick in some much-needed money. The foundation was a nonprofit entity that is independent from the hospital. The board members solicited donations from wealthy residents in the area, as well as voluntary payroll deductions from employees.

The money was supposed to go toward gifts that the hospital could not afford through its general fund. In past years, the foundation spent $420,000 on gastroenterology equipment, $100,000 for rooms dedicated to chemotherapy and $1.1 million for construction of the hospital’s cancer center.

But some foundation board members said they noticed a decrease in funding from employees when Hayes became CEO, even though the same number of employees still supported the program.

“They kept taking it out of their payroll but quit paying us,” said Fant, the hospital’s former CEO who remained on the foundation board.

Hayes also sent a letter to Fant asking the Foundation to give Hutcheson money for the Disproportionate Share Hospital program, an offer for extra government funding. Under the program, hospitals that treat a larger-than-average number of low-income patients get extra money since Medicaid usually does not cover the full cost of seeing those patients.

To qualify for the program, the hospitals also have to pitch in money, which goes into a pool and is divided up. Hutcheson would receive more money than it puts in, given the high number of Medicaid patients it treats.

But the hospital didn’t have enough cash to throw into the pool, so Hayes turned to the foundation.

Some of the nonprofit’s board members decided they would not give Hayes the money. They didn’t believe Hayes would ever pay them back, despite his promises. Plus, multiple board members said they thought the IRS would not let them use their charity fund to cover the hospital’s operating expenses.

When Hayes first asked for the funding in February 2013, according to an email from board member Betts Berry to the CEO, a lawyer advised the foundation not to give Hayes the money for the hospital. Hayes asked again that fall, and again the foundation said no.

“Leonard, ?????” Hayes wrote to Fant in an email on Oct. 30, 2014, after hearing the news. “Who exactly is your money that you raised in Hutcheson’s name supposed to benefit?”

Eight minutes later, he wrote another email to Fant: “I hired you at (North Park Hospital) when nobody would touch you (after Fant left Hutcheson in the early 1990s). And you send me that letter?? Are you kidding me? That letter was b******t and you know it.”

“I’m sorry you feel that way,” Fant wrote back. “It was a unanimous decision.”

“And mine is also unanimous,” Hayes responded. “We both know where our loyalties are. Mine are to Hutcheson and Hutcheson only. That is the last request you’ll ever get from me.”

(From left) Kim Plant, Hutcheson Director of Physician Practice Operations, Tiffany Richards, Hutcheson Medical Staff Coordinator, Michelle Chandler, Hutcheson Occupational Health, and Jennifer Frazier, Hutcheson Director of Case Management, sit in the Catoosa County Administration Building.

Hutcheson’s final descent as a public hospital began in September, when the hospital’s staff laid off 58 employees through two rounds of cuts. The next month, the hospital laid off about 75 more employees.

Hutcheson also cut services: the Chickamauga Family Practice Clinic, the Battlefiled Lung Specialists, the Multi-Family Practice Clinic, the intensive care unit.

Two months after that, on Dec. 4, as a trustee overseeing Hutcheson’s finances in bankruptcy court saw no chance for the hospital to survive, administrators locked their doors. They wrapped plastic coverings around the hospital’s signs. They pushed boards against the windows.

The lobby, once a beacon for a hopeful future at Hutcheson, sat abandoned, and dark.

A hospital built generations earlier with federal funding and local residents’ money had failed because of big factors like the economy and Medicare funding levels. But it also failed because of a smaller, more human issue: the inability to unify a collection of visions. From politicians, from CEOs, from lawyers.

Market forces that are spelled out in business school classes put Hutcheson in a hospital bed, but many employees believe pride from the men at the top pulled the plug.

Paramedic Sandra Gray (right) comforts RN Katrina Park upon hearing that staff will be laid off at Hutcheson Medical Center on Tuesday, Nov. 24, 2015. "I don't want to go anywhere," Park said, who has worked at Hutcheson for fifteen years. "I've worked a lot of places and there'll never be another Hutcheson. We are family. We love this community."

The night before the end, the staff members who remained at the hospital through the changes in CEOs, the management deal with Erlanger and the bankruptcy filing gathered for one last night. They brought mashed potatoes, green beans and roast beef. They shared old stories. And when the morning came, they said goodbye and looked for new jobs.

Kelley, one of the nurses, remembered a time when a boy in a new University of Tennessee football jersey arrived in the emergency room with a broken arm. She watched the boy cry as the staff cut through his jersey. Then, she watched another nurse leave. The nurse returned with another jersey, which she bought with her own money.

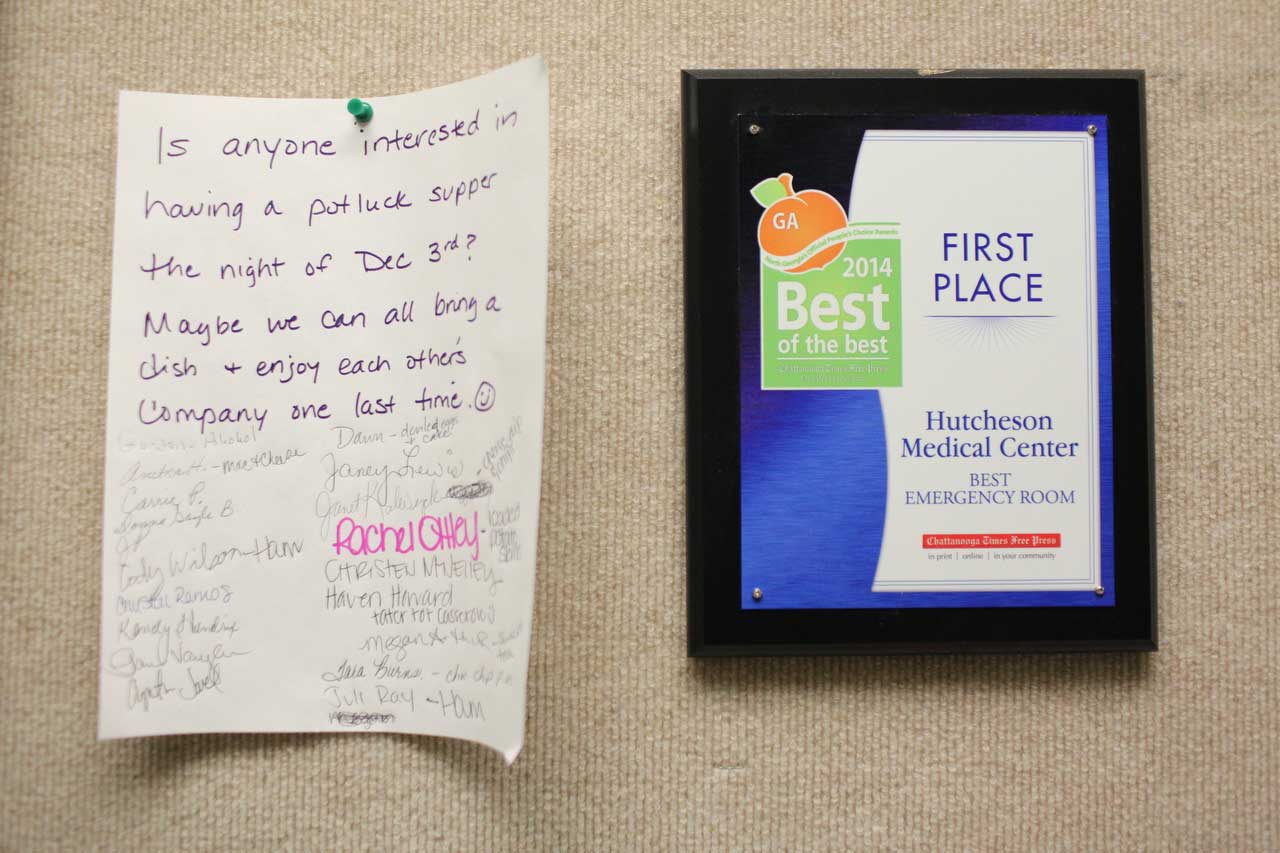

A potluck supper sign up sheet hangs in the hallway at Hutcheson. In December, when the hospital was set to close, doctors, paramedics and nurses came to show support and tell stories about their favorite days at Hutcheson.

Kelley said Hutcheson’s staff always seemed special compared to other hospitals, even as they waited for the end.

“I don’t know what the magic was,” she said. “I don’t know if it was because of the history of the hospital. I don’t know if it was because times were tough and in tough times people stick together.”

Said Scott Lewis, a paramedic: “A lot of those people who (were there at the end) have been there for 20, 30 years. A lot of them could have retired, but they worked there because that’s what they wanted to do.”

Said Zoila “Zee” Leon, a former director of the emergency department: “I’ve never worked anywhere where I’ve seen so much heart and so many people dedicated to a place. People came and went. But there was a core group of people who stayed there no matter. Their downfall has always been administration.”

Two weeks after Hutcheson shut its doors, on Dec. 22, the hospital opened again. This time, a new company was managing the place. Leaders from ApolloMD, the company that took over the ER last summer, agreed to buy the hospital for $4.2 million. They will try to do something that previous administrations have failed to do: Keep the hospital off life support.

So far, they have re-opened the emergency department, the pharmacy and the lab. Their administrators say they will do more, will turn it into a successful hospital once again.

They have given the hospital a new name: Cornerstone Medical Center. The hospital will change, they said. They will start small, and they will build. And they will be patient.

Staff members, meanwhile, said that they will wait, and watch.