S CHURCH MEMBERS ACROSS AMERICAwere sharing copies of “When Helping Hurts,” Sherri Brown picked up the book in 2012 in LaGrange, Georgia. Brown, a Southern Baptist preacher’s wife and former journalist, didn’t need to be convinced that Christians needed to do more to help the poor.

S CHURCH MEMBERS ACROSS AMERICAwere sharing copies of “When Helping Hurts,” Sherri Brown picked up the book in 2012 in LaGrange, Georgia. Brown, a Southern Baptist preacher’s wife and former journalist, didn’t need to be convinced that Christians needed to do more to help the poor.

Leaders in Troup County had hired her to launch a local chapter of Circles USA, a successful national program aimed at teaching families in poverty to stabilize their lives by connecting them to the middle class.

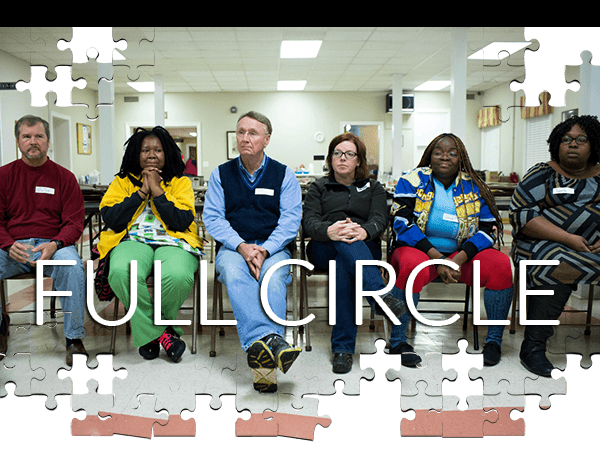

A man walks toward a public housing unit in LaGrange, Georgia in December. Nearly a fourth of the town’s population lives in poverty.

In LaGrange, an old textile mill town, nearly a fourth of the population lived in poverty and more than half of the county births were to single mothers. But in 2010, Kia Motors built a $1.2 billion auto plant, pumping thousands of new jobs into the area. Three years earlier, county and city leaders, recognizing the need to rebuild their local workforce, formed a strategic planning committee made up of all the county’s leaders and a local foundation to study how to address the county’s economic needs.

But when Georgia Institute of Technology published a study diagnosing the county, the committee couldn’t ignore the number of people living in poverty, the high teen pregnancy rates and low graduation rates, said then-Commissioner Ricky Wolfe, who was chairman of the committee at the time.

“We didn’t know what to do about it, but we felt strongly that poverty had to be addressed,” he said.

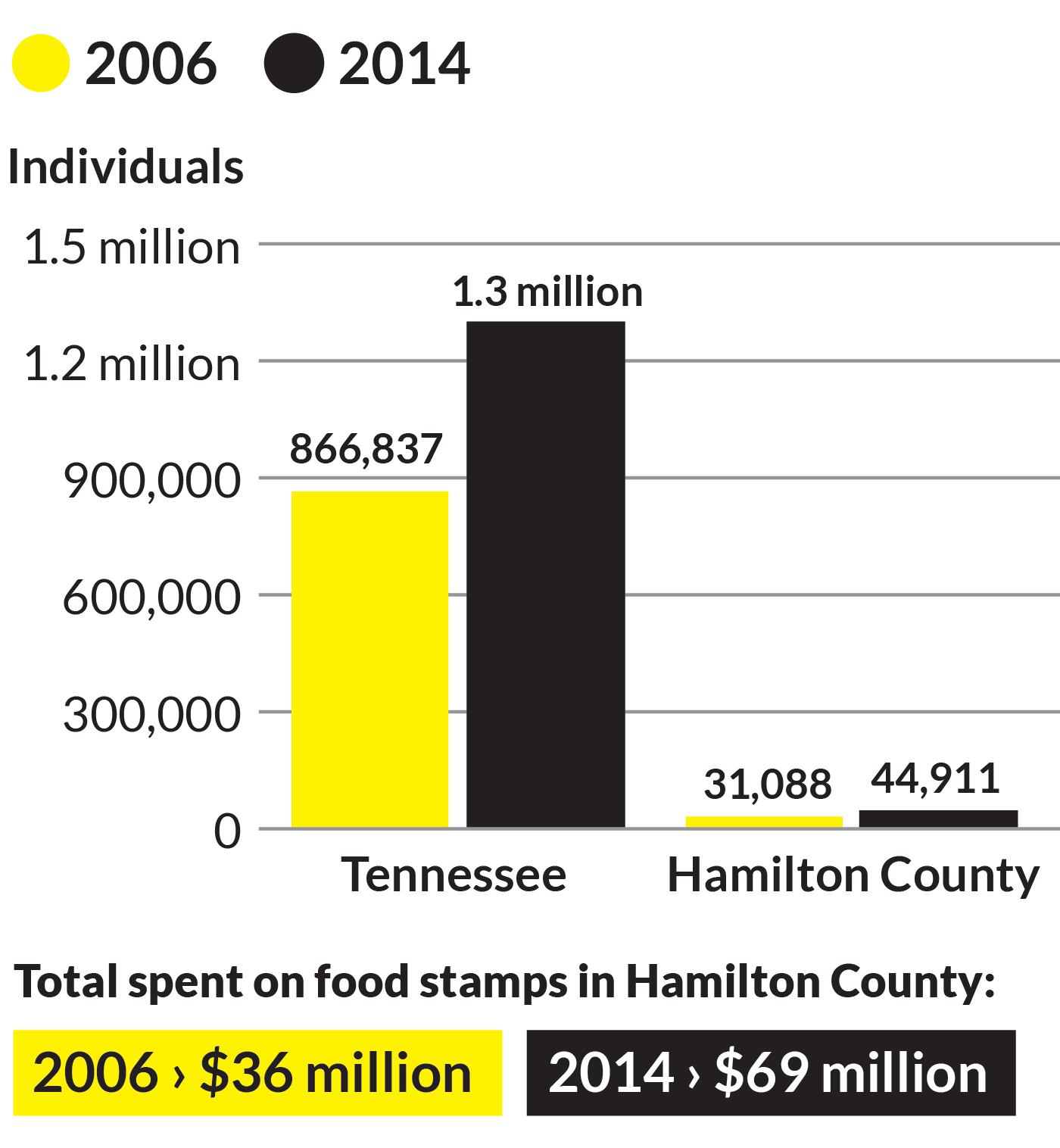

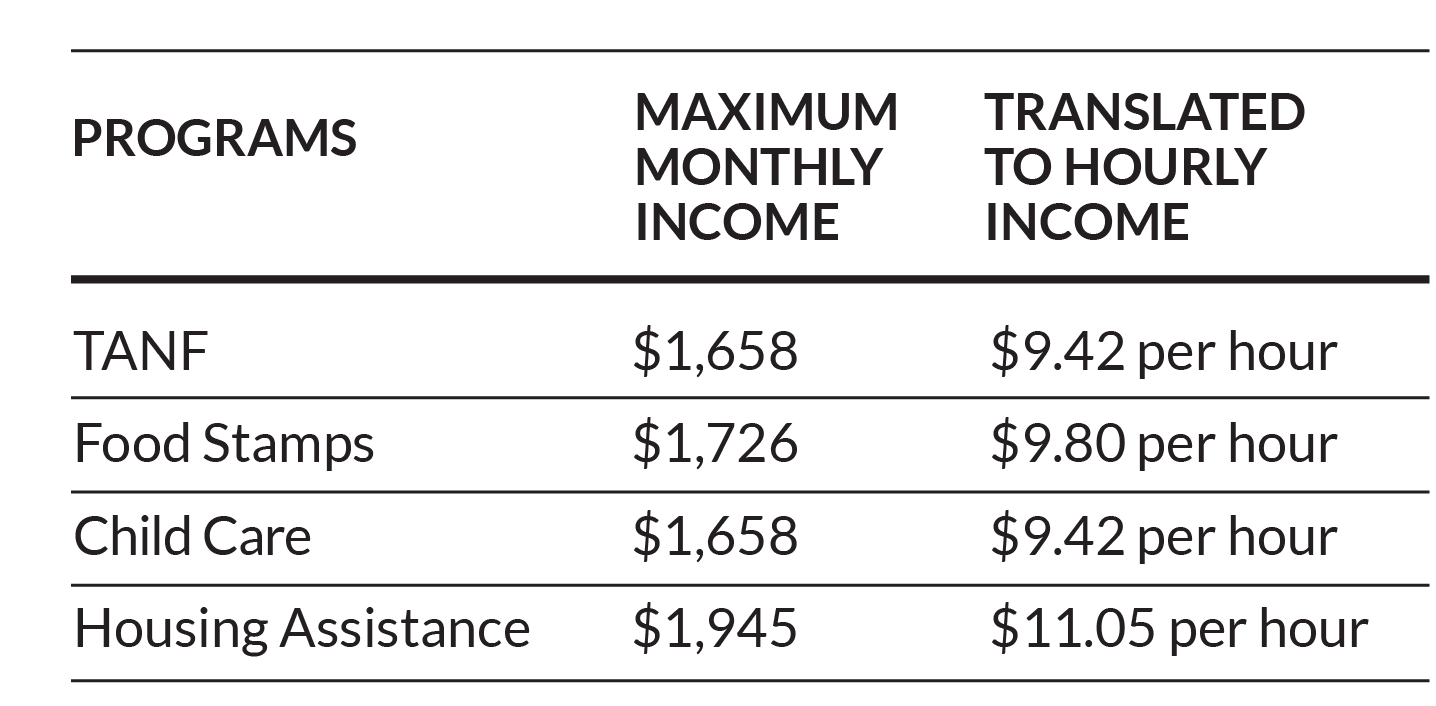

Source: Tennessee Department of Human Services

After months of research, the committee found Circles, a community-based program known for moving families out of poverty developed by Scott Miller after more than 20 years of study.

When Miller was in college, he said, he began to notice the ineffectiveness of poverty alleviation efforts when he volunteered at a homeless shelter. Agencies were focused on solving their piece of daily emergencies, but he found they treated poverty as if it could be fixed with policies instead of relationships.

“If the plan is more oriented to the crises of the day, it’s ‘I have a housing problem. I have a car problem,” he explained. “To do the whole work, you have to be committed to the whole work. Someone has to be accountable. It is the biggest reason we don’t get rid of poverty. Everyone just has one piece of poverty.”

So he developed a program to help build social and economical capitol for families in poverty, starting with weekly meetings that offered dinners, child care and facilitators. The linchpin was bringing in the middle class.

Once the idea caught on, Circles expanded to more than 70 communities in 23 states and parts of Canada. It’s a model the United Way of Greater Chattanooga plans to introduce locally.

The Circles model also caught the attention of Brian Fikkert, a Covenant College professor and co-author of “When Helping Hurts.” In his 2009 book, he wrote that the program, though not faith-based, was an example of how churches could help the poor help themselves and, in the process, rebuild their community.

Director Sherri Brown of the Circles of Troup County chapter talks to an attendee before the group’s meeting in December in LaGrange, Georgia.

After Troup County leaders decided to fund a Circles chapter through a public-private partnership, they called Brown, who at the time worked for the local newspaper, and asked her to write a story.

When Brown began to research the Circles model in 2012, she read how those in poverty were taught the hidden rules to the middle class. In turn, the middle-class volunteers were taught what it’s like to be born into poverty. After the course, each person in poverty was paired with two or three middle-class volunteers, called their “allies.” Then the relationship went beyond a class. Each of the allies committed to helping those in poverty for at least 18 months, becoming a coach and a cheerleader and a hand-up to the middle class.

Nationally, the results were impressive. Of the 518 people who stuck with the program for more than six months in 2012, 92 percent found safe housing, 73.6 percent got reliable transportation, 38.1 percent opened a new savings account and 33 percent obtained new employment.

After Brown’s article was published, she applied to become the director of the local Circles chapter.

dozen low-income women came to Brown’s first class in late 2012 at a Baptist church in LaGrange. Among them was Inetha Hatten, a grandmother who couldn’t afford to buy shampoo or toilet paper, and Tameka Johnson, a single mother of two, who wanted to become a nurse. Seven women eventually graduated from the 13-week class.

dozen low-income women came to Brown’s first class in late 2012 at a Baptist church in LaGrange. Among them was Inetha Hatten, a grandmother who couldn’t afford to buy shampoo or toilet paper, and Tameka Johnson, a single mother of two, who wanted to become a nurse. Seven women eventually graduated from the 13-week class.

Hatten was paired with Brown’s husband, Greg, who pastored the 500-member Western Heights Baptist Church in LaGrange. Johnson was paired with Bobby Carmichael, who served on the county’s strategic planning committee, and his wife, Molly. Both Greg Brown and the Carmichaels say they were moved by the women’s faith, even though they lived in poverty. They also were surprised by how difficult it was for the women to become self-sufficient.

Research shows one of the most difficult barriers to leaving poverty is overcoming the hurdle of losing government assistance. Eligibility for these programs is generally based on income, with benefits phasing out as earnings increase. But an increase as small as $50 a month can cause a person to lose hundreds of dollars’ worth of program benefits, and often the gained income doesn’t cover what’s lost, creating what researchers call the “cliff effect .”

Note: Some government programs offer transitional assistance.

Source: Tennessee Department of Human Services and The Chattanooga Housing Authority

Greg Brown’s first goal to help Hatten was to open a bank account in her name. When she arrived at the bank alone, she was shooed away by the teller. The next day, Brown put on a suit and tie and went back to the bank with her. The bank employee’s demeanor changed entirely.

“Rev. Brown, how can we help you?” asked the employee.

Next, Brown tried to help Hatten get a job, made difficult by a felony conviction on her record. Brown finally convinced a friend to give her an interview. She was hired part-time and eventually offered full-time work as a trainer for a program that helped connect people who had work barriers find employment. Later, she was asked to serve on the housing authority’s board to represent the residents’ needs. A few months later, the housing authority hired her to become a community liaison. Now she speaks to local groups and also sits on the citizen police commission. Meanwhile, she is working to get her criminal record expunged.

“My life came back to me,” Hatten said. “Before I was just existing; now I have a platform.”

Tameka Johnson stands for a portrait outside her medical assisting job in December in LaGrange, Georgia. Johnson has been with Circles for three years, and she is now in nursing school.

When the Carmichaels were first paired with Johnson, they met her every Friday morning at McDonald’s. She kept track of every expense in a little pocketbook. They found she was meticulous and determined to go back to nursing school. She was able to find a job as a medical assistant during the day and take classes at night, while the Carmichaels watched her children.

Circles leader Sherri Brown didn’t let the barriers to poverty stop the women in her class from moving forward. She convinced the local workforce development office to visit her class and help women enroll for school assistance, saving them hours and keeping them from having to take time off work to visit the office during business hours. She helped organize a committee to study how to solve the county’s lack of public transportation after women in her class explained how expensive it was to get to places in a taxi if they didn’t own a car.

But the hardest people to work with were often the charities and churches, the Circles volunteers said. Many offices closed at 5 p.m., and they weren’t open on the weekend. Sometimes, they sent women away when they didn’t fill out the right paperwork. While many church members were generous with their time and money, other churches tried to dictate their own terms to volunteer.

Sherri Brown’s biggest frustration was when a Christian would tell her that her Circles class was helpful but what the women really needed to turn their lives around was Jesus.

“What makes you think they don’t have Jesus?” she asked.

One woman in her class drove her car without brakes. She told the class that she had loaded her three children in the car, pumped the brakes and prayed for God to keep them safe all the way to work, and he did. Another woman cried when Sherri Brown brought her food. She said her pantry was empty, and she had prayed for enough food for the week. Brown said she realized, when the women in her class pray, “Give us this day our daily bread,” they actually mean it.

(Top) Tujuana Baker looks into a pot of pasta being served before a meeting of the Circles of Troup County chapter in December in LaGrange, Georgia. Before every meeting attendees eat dinner together, and during the meetings childcare is provided.

(Middle) LaTwala Winston looks on while Blake Trent shares at the end of the Circles of Troup County chapter meeting on Dec. 17, 2015 in LaGrange, Georgia. Winston told the group that she was able to buy all five of her children Christmas presents and still had money left in her savings account.

(Bottom) Circles of Troup County director Sherri Brown explains the process to apply for loans to Kourtney Clark, left, and LaTwala Winston after the group’s meeting in December in LaGrange, Georgia.

Then late last year, Sherri and Greg Brown became aware that some of the Christians within their own congregation didn’t agree with what they were doing to help the poor.

Ten years ago, Greg Brown had started an Alcoholics Anonymous chapter and invited the participants to visit the church. The back pews began to fill with men who were trying to get sober. Then, their church paired with a homeless women’s shelter, and women with bruises cried at the altar.

When Sherri Brown’s father, a pastor in Chicago, came to visit their church, he looked around and saw the changing climate.

“You’ll stop growing,” he told his son-in-law.

His words were prophetic. The changing demographics created tension in the church and, in 2015, it was one of the reasons cited for a church split.

But Greg Brown realized he couldn’t base the effectiveness of the church on how many people filled the pews or who participated in hospitality work like volunteering in the nursery or singing in the choir. The church was what God’s people did when they left the building and cared for “the least of these,” he knew.

In mid-December, at the last Circles meeting of the year, Sherri Brown wanted to leave her group on a high note. The women had just been introduced to their allies. Each woman had written down her goals: Build a $500 savings account. Ace an upcoming job interview. Finish nursing school.

The lists were specific and obtainable, and Sherri Brown felt like they were as ready as they could be to practice what they had learned over the 13-week course.

Each woman had already come so far. Johnson was halfway through nursing school, working part-time at a clinic. Carole Hopkins had a job interview. LaTwala Winston saved enough money to buy her five children Christmas presents and still had $384 saved in the bank.

Of the 34 families that participated in Circles in the last three years, those who stayed six months or longer saw their total debt cut in half while their assets increased 366 percent, Sherri Brown told the women at the December meeting, pointing to the numbers, written in red Sharpie on a page tacked to the wall.

Yet the most significant changes, she thought, but didn’t say out loud, had come from the middle-class church members who volunteered to help the women.

When the Carmichaels, who are Methodists, joined three years ago, they said they brought their preconceived judgments to their new relationship. But Johnson had become like a daughter to them, said Molly Carmichael, whose children were grown, and they are constantly encouraged by her faith in God. Now, they try to convince their Sunday School class, their church and the surrounding denominations to volunteer and to fund Circles.

“This whole program should be on the backs of churches,” Bobby Carmichael said.

Because the mission of Circles, he said, is the mission of the church.