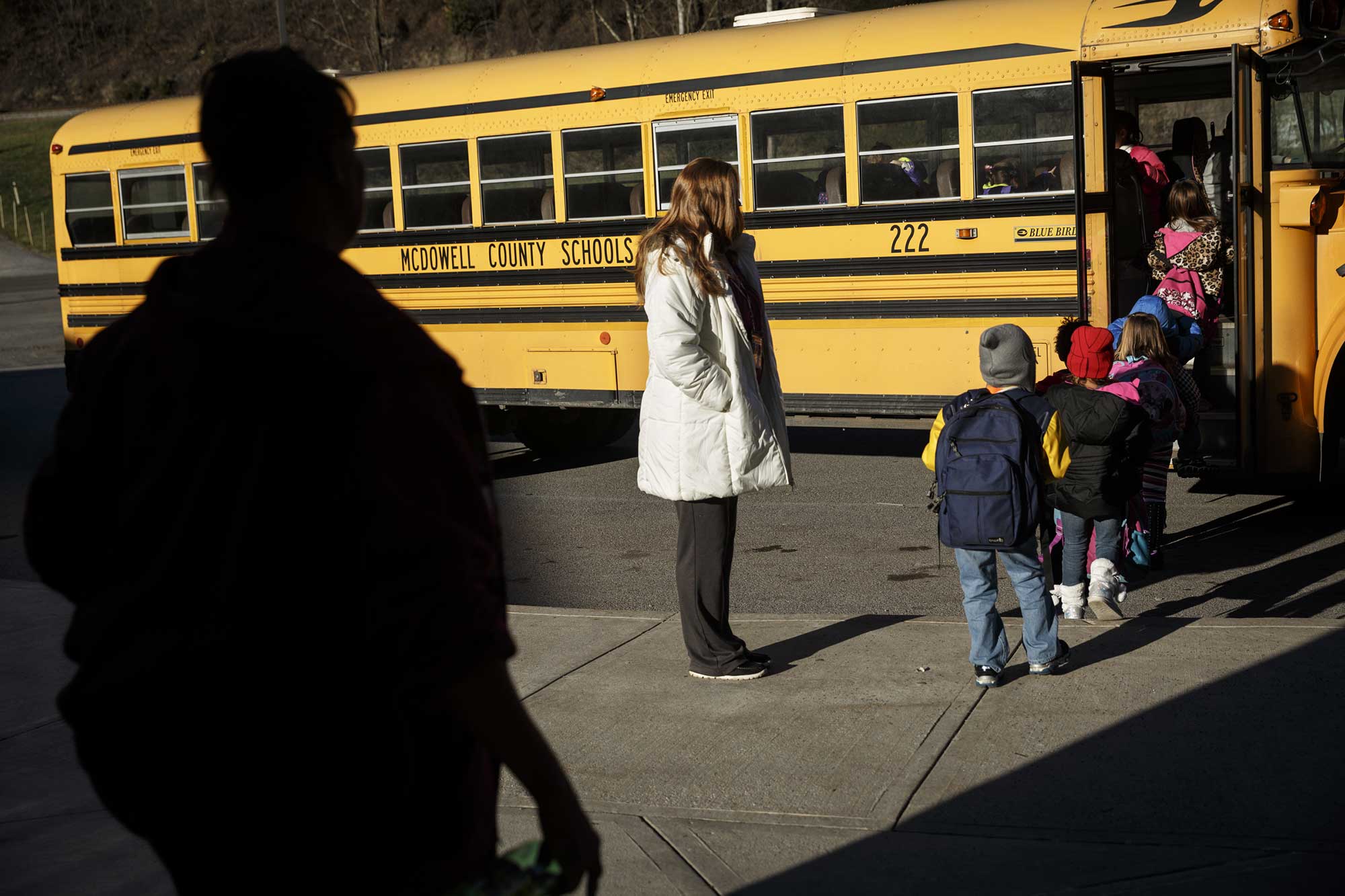

nce classes endedand the school bell rang, scores of bouncy children flooded into the cafeteria for dinner at Southside K-8 School, one of seven elementary schools in McDowell County, West Virginia.

nce classes endedand the school bell rang, scores of bouncy children flooded into the cafeteria for dinner at Southside K-8 School, one of seven elementary schools in McDowell County, West Virginia.

But just as the children were digging into their food and cartons of juice, several sprang up and ran. In the corner of the room, a familiar face appeared and the children raced to be noticed.

Debbie King, a mild-mannered and gray-haired 61-year-old former teacher, had been retired from the school system for a few years, but she came back almost every week to check in on her babies, as she called them. She combed fingers through their hair, held their small faces in her hands and hugged a few into her side.

“Miss King.” “Miss King.” “Miss King,” the children chirped, pulling on her clothes, elbowing others aside for an extra hug.

“Hold on. Hold on. Let’s each take turns,” she said.

Some students hadn’t seen King in weeks. A recent winter break isolated many at home in the mountain hollows, and some of the children were shaking off holiday loneliness.

Some kids may hate school, but not the ones in McDowell County.

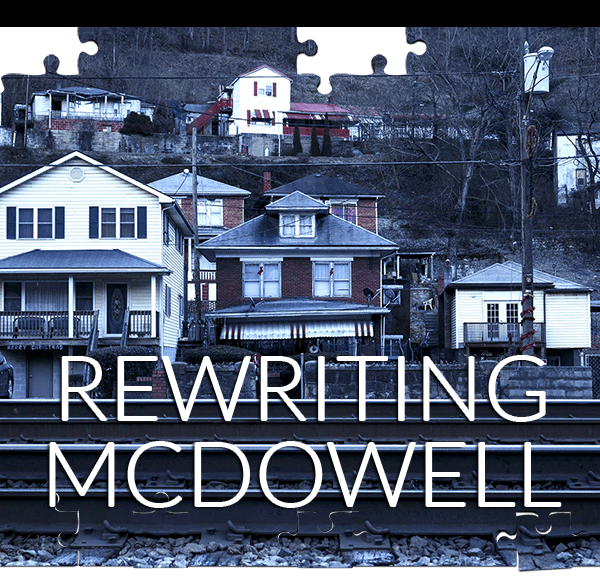

Once a place that held tremendous political sway over West Virginia, McDowell County had become one of the poorest and sickest in America.

Families had been ripped apart by joblessness, drug addiction, depression and lack of opportunity. The brokenness ran so deep, locals said, almost half of children weren’t even living with their biological parents. Drug overdoses and suicide had become the leading causes of death.

And what was left of the once thriving mining town mirrored what was happening all across America, thanks to the steady and precipitous decline of the nation’s working class. It stood, too, as a warning to cities such as Chattanooga about what happened when poverty was left to fester.

A rare experiment with the bold name “Reconnecting McDowell” was taking shape, however.

Volunteers, trying to right the ship, were building partnerships and excitement, and by 2016 their work appeared to be nudging the community toward change. In decades, though, they hoped their leadership in southern West Virginia could teach the entire county what was possible when poverty became a middle-class concern.

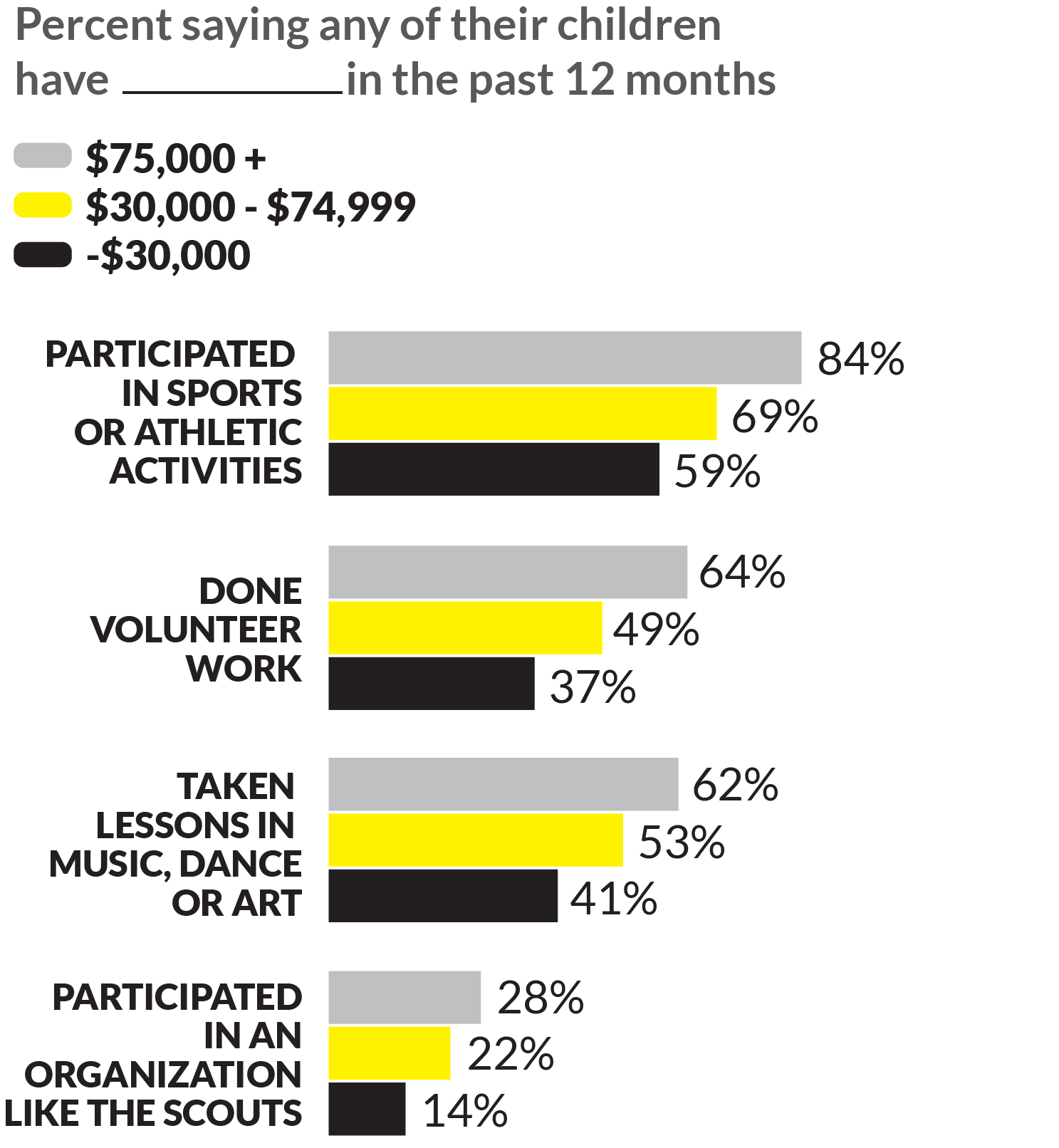

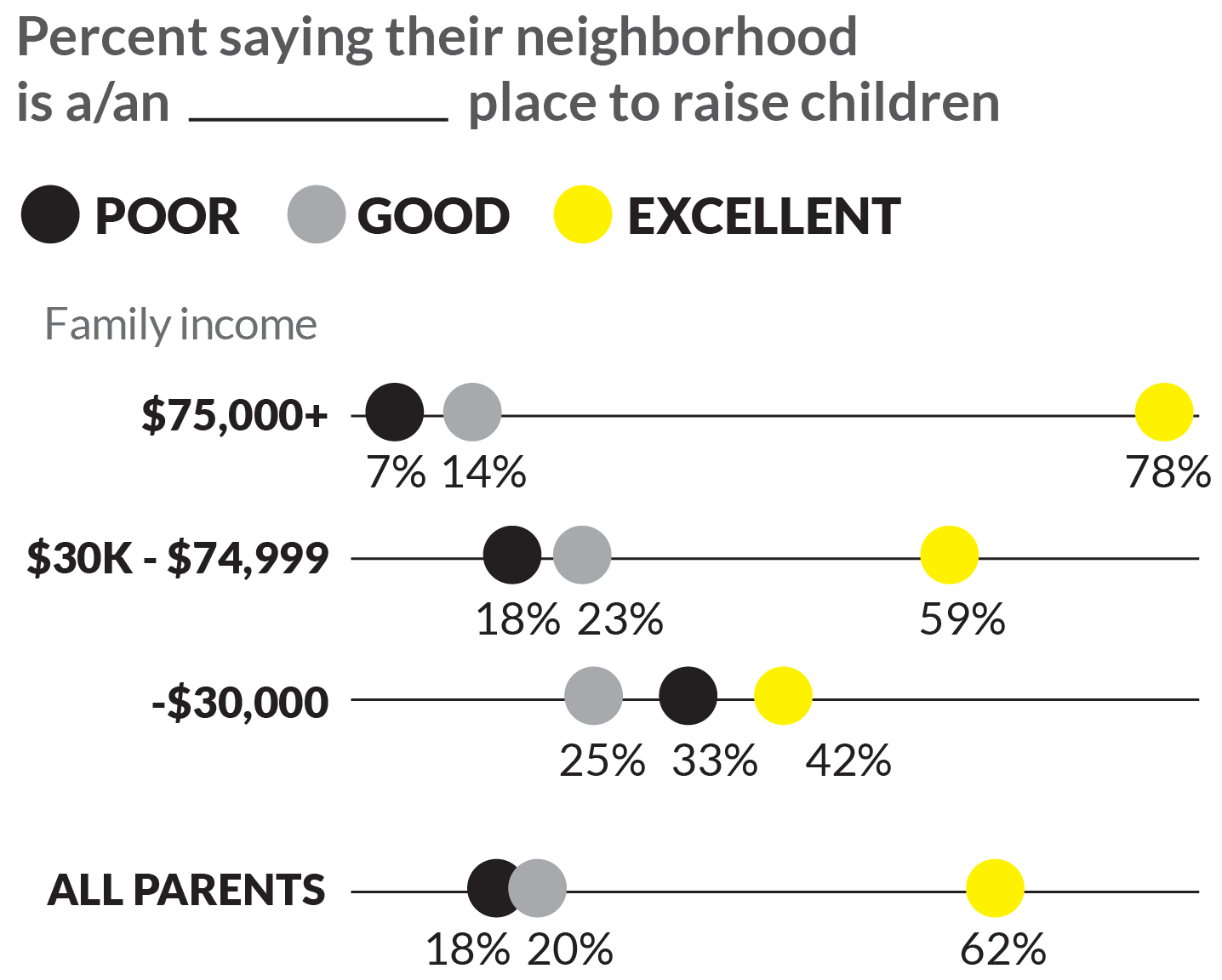

Note: Based on parents with at least one child ages 6 to 17. Income is annual family income. Source: Pew Research Center

Communities all across America had become frayed and the country needed a revival of sorts, those involved said, with a significant amount of research to back their case.

While Reconnecting McDowell — comprised of hundreds of locals and dozens of state and national nonprofits — had formed committees, goals and plans, it refused to be a slave to metrics. Instead, many in the community were taking stock of their personal values and experiencing a change of heart.

McDowell County needed to return to the message its churches preached, locals said. Maybe it was as simple as embracing the Golden Rule: “Love your neighbor as yourself.” And after four long years, the hard work of reknitting the torn community fabric was underway.

After finishing with hugs, King pulled away from the crowd of children when she saw Maddie Hicks timidly approach.

A 16-year-old high school student, Maddie was the bright but quiet daughter of a single mother who couldn’t work because of a back injury. To make ends meet, Maddie and her mother lived with extended family. Her father wasn’t involved in her life. And she was just one of many local children, King knew, who needed someone to pay attention to them.

King and Maddie had met at a Baptist church the year before, and not long after their introduction, Maddie called King for help during a difficult homework assignment when her mother suggested she reach out.

King had been an educator for decades and sometimes wept over local children’s wasted potential. Poverty might dim or bury potential, but it didn’t erase it, she believed.

Maddie dreamed of becoming a writer one day, and teachers told her she was good at composition. But who was going to talk with Maddie about the difference between Hemingway and Faulkner, King thought. Who would counsel her to think clearly about the earnings potential of a liberal arts degree, and then tell her to follow her heart?

When King asked Maddie if she had a mentor or wanted a mentor, Maddie hadn’t known what to say.

“There aren’t many … people willing to help,” Maddie told her that night. “No one notices.”

“I noticed you,” King said.

o road in or out of McDowell County, West Virginia, is simple or straight.

o road in or out of McDowell County, West Virginia, is simple or straight.

Coal trucks teeter along switchback roads that bend over the heights of Appalachia and descend through pockets of valley crowded by old, coal-company homes.

Shoulderless roads force a focus that can divert attention from the soaring landscapes, but the grandeur — while a deep source of pride for those with generational ties to the mountains — is rarely why people think about or visit McDowell County anymore.

The county, with a population hovering around 20,000, has only a handful of restaurants and two family-owned hotels. Even gas stations are hard to find.

After natural gas, a cheap energy alternative to coal, became more widely available, the mining industry fell into decline. Beginning in the 1970s nearly 100,000 middle class individuals fled, data show, and in a single year, 1981, more than a hundred businesses closed shop.

Homes were left behind to crumble in the hills, and, by 2016, county officials said more than 5,000 structures in the area needed to be demolished.

Photos from more than a century ago showed crowded sidewalks and a bustling city center. A stronghold of the United Mine Workers of America and the Democratic Party, the county held enough power to flip even national elections, many said.

It also was a place famed for helping poor and minority children get ahead. Black professionals flocked to the county before 1930, attracted by the spending potential of a wage-earning black population, and historians note African-Americans held significant political power and openly did business with whites, while many just like them faced discrimination all across America.

(Top) A sign in the town of Coalwood, West Virginia, indicates that it is the home of the Rocket Boys, made famous in the movie “October Sky.” Coal played an integral role in the formation of McDowell County, and its legacy remains in the form of the still-standing company-built homes and namesakes like “Coalwood.”

(Bottom) Coal is poured from a chute in McDowell County. Though the coal industry still exists in the county, the prosperity that it brought to the county has waned as jobs have dried up.

Homer Hickam, who ascended from poverty to NASA thanks to the attention of a kind teacher, reflected the region’s past mobility. His story was made popular by the movie “October Sky.”

A local newspaper declared the county’s unique brand of community on its masthead: “The Free State of McDowell.”

Now, though, journalists — struck by the county’s stark poverty data — came from all over the world to gawk at the emptiness.

The median household income in 2014 had fallen to $23,607, far below the state median income of $41,576 and the national median income of $53,482. The percentage of population in poverty had reached 35.2 percent, double the poverty rate of both West Virginia and the U.S. as a whole, and almost half of all children were living below the federal poverty line, data show.

Some locals had resorted to running cameramen, trying to capture pictures of the houses disintegrating in the hills, off their property with shotguns, said Greg Cruey, a math teacher at Southside K-8 who drove from Virginia every day to get to work. On Facebook, locals who agreed to interviews with visiting news organizations were chided for aiding and abetting “poverty tourism,” he said.

“Church groups come up all the time,” he added. “But we have to orient them and tell them they can’t talk about how poor they think the children are while locals are listening.”

The roots of America’s 1960s-era War on Poverty were in the mountains of southern West Virginia, and, in many ways, McDowell County answers the question of whether the war had been won. After all, McDowell County residents Chloe and Alderson Muncy, who were raising 13 children and had no income at the time, received the nation’s first food stamps in May 1961.

But the deep, generational poverty being experienced in McDowell County in 2016 is different from the low-wage working-class poverty families lived through decades earlier.

During the 1990s, when McDowell County lost its major mines because of the downturn in the American steel industry, family breakdown became widespread. Mining had always been a cyclical industry. So locals were used to having work and then not having it, but most believed the jobs would come back.

When they didn’t, those left behind in poverty had no way to support their children. Educational attainment was low. Only 64 percent of high-schoolers graduated and only 6 percent of the population had a college degree.

And many crumbled under the depression and addiction the lack of opportunity seemed to spawn. Forty-one percent of children were born with drugs in their system and went on to have serious health issues because of neglect or abuse.

Decades ago, families weren’t so divided by class, experts on American civic life say. Decades ago, however, Americans weren’t so politically polarized either.

Cruey can remember when the middle class and the working class blended together and cared for their neighbors’ children. In Charleston, the state capital, Cruey said, it’s easy to find government leaders, wealthy business people and professionals who grew up poor in southern West Virginia but made it out decades ago.

Today, those stories are few and far between, he said.

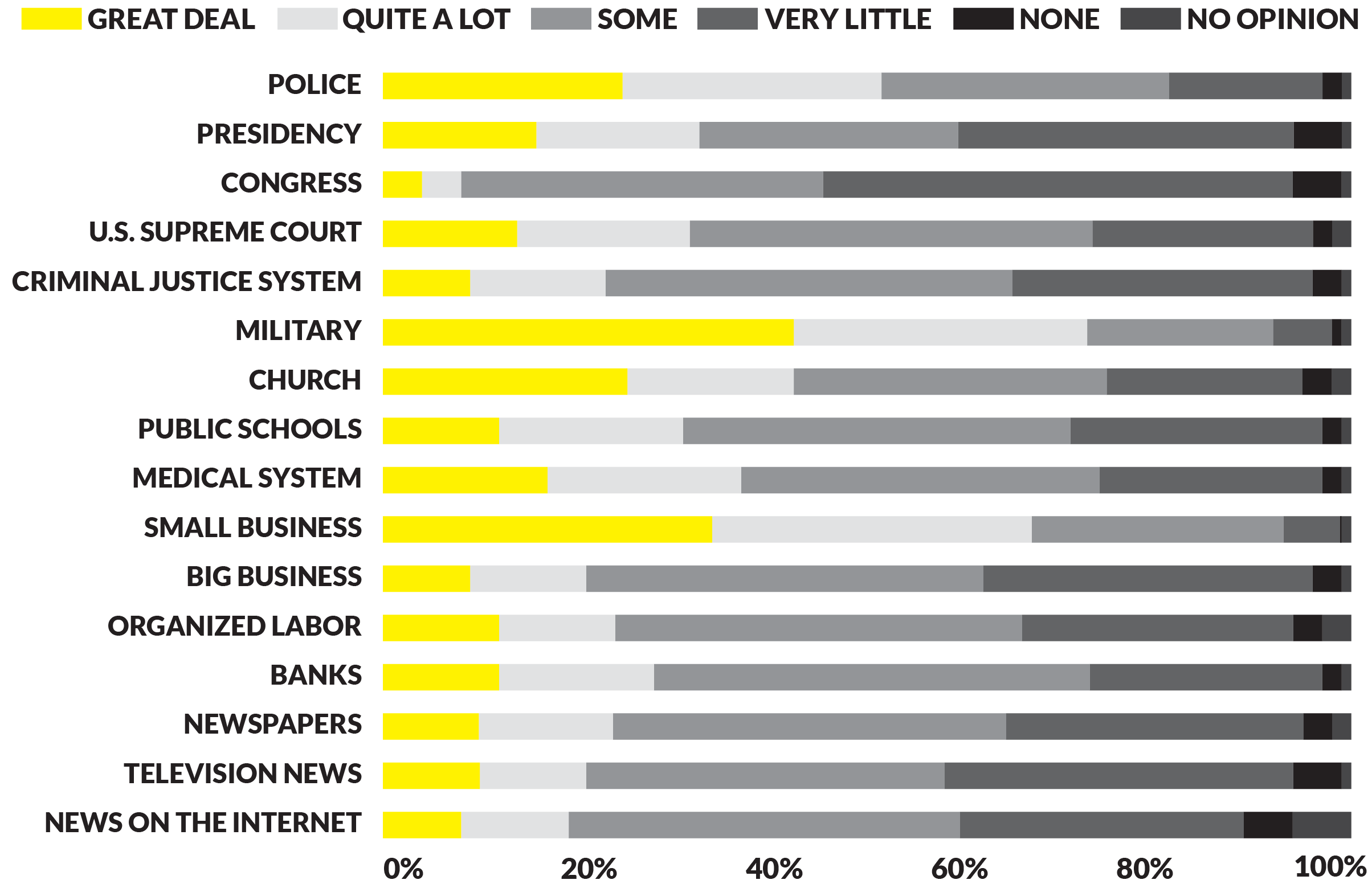

Note: Numbers have been rounded. Source: Gallup

While McDowell County rivals Chattanooga in churches per capita, the faith community had lost its impact, locals said. Many who sat in church pews on Sunday morning were bitter about what entrenched poverty had brought to the area and judged the poor for how they hurt themselves.

“In the past, everyone was clannish,” said Dan Riley, director of the McDowell County Redevelopment Authority. “Community isn’t strong here anymore. A lot of people have given up. The mines wore people down. It all took its toll.”

Cruey and other educators were seeing children so neglected that they entered school neither socially nor academically prepared. No one had explained sharing. No one had told them why it wasn’t appropriate to run down a hallway and hit other kids, he said.

And these shifts were a national problem, said Harvard University political scientist Robert Putnam.

Class segregation — accelerated in the past decades by the demise of marriage, the divisive nature of politics, the rising importance of college and a growing distrust of institutions and strangers — was destroying the futures of children and communities, Putnam argued in his prolific research on the frayed nature of American community.

Poor children were growing up alone. Their parents had little money or stability to offer them. Left out of churches, clubs, decent schools, safe neighborhoods and sports, they had lost all trust in society. It was no wonder many were so violent and careless. They had little to lose, Cruey said.

“When I grew up, parents were responsible for teaching behaviors and how to respond in circumstances,” Cruey said. “But as a teacher, I have taught things like how to apologize and what is a real apology.”

Untended, the isolation of poor children in rural pockets such as McDowell County and in inner-city neighborhoods such as Alton Park or East Lake in Chattanooga would escalate entrenched, generational poverty and mount to a national crisis, Putnam and others cautioned.

In McDowell County, the crisis had long ago arrived.

t the beginning of 2016, something good finally seemed to be taking place in McDowell County, and many in downtown Welch, the county seat, were buzzing about the possibilities.

t the beginning of 2016, something good finally seemed to be taking place in McDowell County, and many in downtown Welch, the county seat, were buzzing about the possibilities.

For the first time in 50 years, a permit was being issued to build a multistory residential and commercial building, and it was one of the first fruits of Reconnecting McDowell, the community-building effort that had connected locals such as Debbie King and Greg Cruey to a cavalry of outside support.

“I got the plans,” said Bob Brown, a supporter who sailed into Riley’s office from the state capital one January morning with a large roll of paper under his arm.

Shoulder to shoulder, Brown and Riley spread the architectural drawing across Riley’s wooden desk.

One of the biggest obstacles to helping students escape poverty was the county teacher shortage. For years, schools had limped through requirements with a glut of uncertified or temporary staff. Teacher turnover was high, hovering each year around 30 percent.

“The teachers we do have are novices,” said Cruey, a union representative for the school system. “The number of seasoned professionals in classrooms are few and far between. Every year you start with a whole new set of teachers.”

For some new teachers, concentrated Appalachian poverty was tough to swallow, but most left because it took almost an hour to reach “civilization” in almost every direction, said Cruey.

The housing stock in the county was the worst in the state, officials said, because homes had been built quickly and cheaply by the mining companies. Most teachers who had jobs in the county came in from out of state. Long and winding commutes were common for teachers and government employees.

So when the group from Charleston, West Virginia, came with their national and state partners to launch Reconnecting McDowell and asked community members what they thought the first step should be, the teacher housing problem was top of mind. The solution, those like Cruey, Riley and King agreed, would be a “teachers village.”

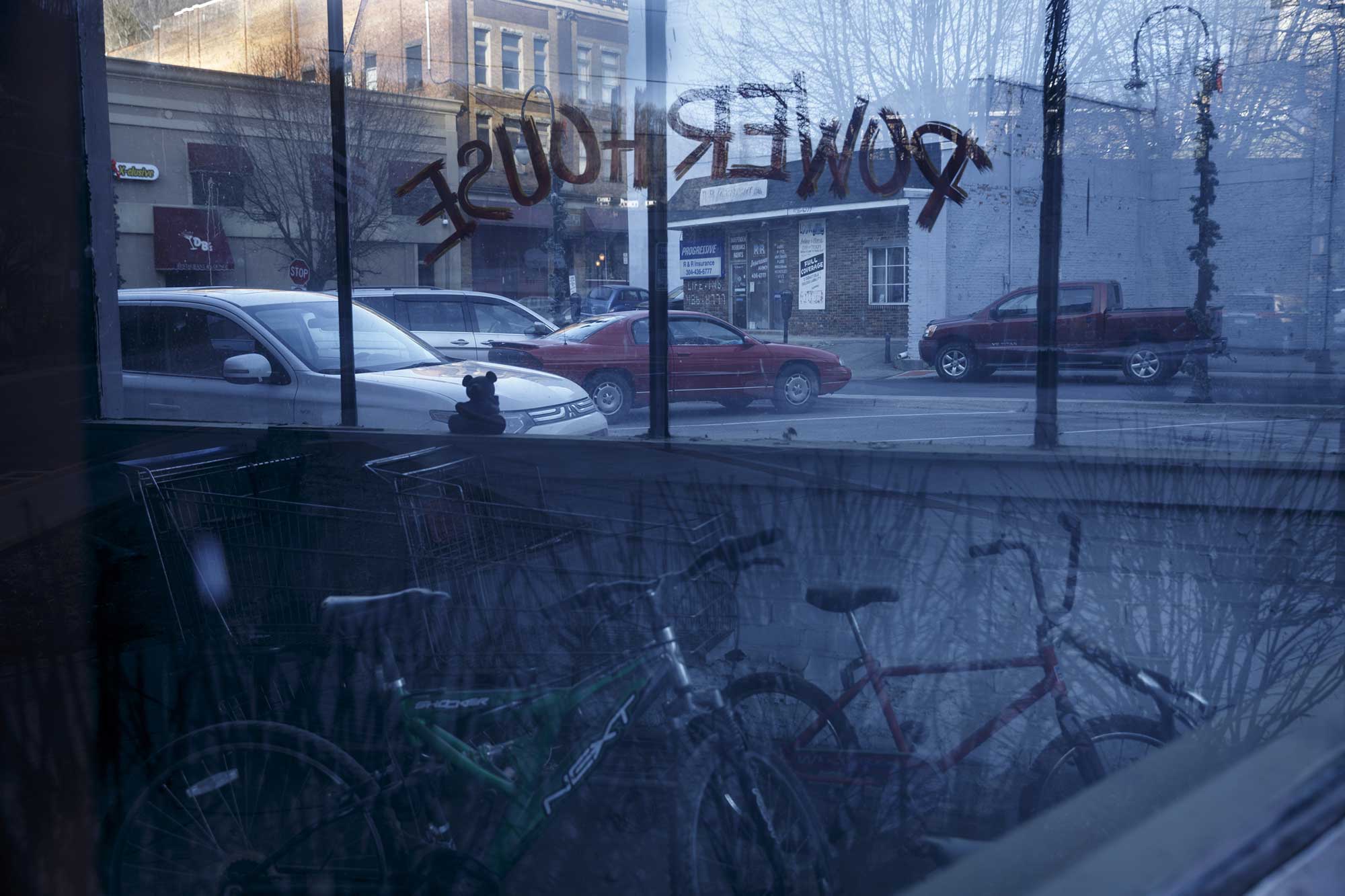

Downtown Welch was full of empty buildings, and one in particular, an old, five-story, former furniture store, would be the perfect spot to build apartment-style housing for professionals and teachers. If people had a nice place to live that was convenient to work, they might stay around longer, the group reasoned.

(Top) An abandoned storefront in Welch is occupied by bicycles and shopping carts.

(Bottom) Brittany Collins, right, and Margie Hall, both of whom grew up in McDowell County, hold a customer’s dog as they help him at the drive-through window of Citizen’s Drug Store in Welch. The store has been a fixture in the town for over 50 years, and it has been owned by pharmacist Shawn Jenkins for seven. Jenkins says he moved to McDowell County because his wife was born there, but he observed that it seems more common for people to leave the county than to return.

On the bottom floor, the plans left room for boutiques, coffee shops or restaurants, which they hoped would open if some middle-class residents began to trickle back in.

“How you doing?” Brown asked Riley after the two studied the plans, which included space for 28 to 32 apartments.

“What hair I have left I want to pull out,” Riley told Brown.

It had taken years to get to the point of just having plans to look at, and much work was left to be done. There was no money to demolish the building. So those involved with Reconnecting McDowell found a business owner willing to donate his construction equipment. Removing cancer-causing asbestos, however, was the challenge of the moment.

“My asbestos guys need to be recertified,” Riley said, before explaining that the county couldn’t afford to pay for the training and recertification, which meant his men couldn’t do the demolition work.

“I found someone willing to do it,” Brown said. “We’ll figure it out.” He patted Riley on the back before leaving to deliver papers to Welch’s mayor.

Riley hadn’t thought Brown, very much the city slicker, would stick around McDowell County when he came with others in 2012 to pitch a shared vision for community restoration. But, without fail, Brown kept coming back.

And seeing Brown breeze through downtown, shaking hands with locals and catching up with them about their families, was beginning to convince Riley that he wasn’t alone anymore.

Aside from the teachers village, Reconnecting McDowell had an economic development plan that called for the county to move away from a mining-based economy, which most agreed would never return to its heyday. The focus, instead, would be on a burgeoning tourism niche. ATV riders were coming to the mountains in droves. The eastern part of the county connected with the Appalachian Trail, and a few businesses had popped up around the new opportunity.

In 2015, for the first time in modern history, tourism had edged out mining as the county’s leading revenue source. Altogether, it seemed to say that change was coming.

Still, fatalism always seemed to tear away at what little optimism he could muster, Riley said.

“People have waited and waited for things to improve,” he said, holding back tears. “I don’t know if I will live to see it turn.”

econnecting McDowell began with Gayle Manchin and an epiphany.

econnecting McDowell began with Gayle Manchin and an epiphany.

In 2001, the state of West Virginia took over the McDowell County school system because of abysmal test scores and low graduation rates. But after 10 years of trying to fix what was wrong, little had improved.

“What is the definition of insanity? Doing the same thing over and over and expecting a different result,” Manchin, a state school board member and the wife of current U.S. Senator (and former West Virginia governor) Joe Manchin, said she told the school board when they were debating, once again, the fate of McDowell County students.

Poor children needed more than what the state and schools were offering them, she knew from having been a teacher. More than anything, she realized, they needed their families restored and their community to care about what happened to them.

Note: “Don’t know” or “Refused to answer” responses not shown. Source: Pew Research Center

In the past, politics had muddied the water, she said, but by 2010 people were so frustrated by McDowell County that many in state government were ready to wash their hands of the situation, leaving an opening for Manchin to argue for a new approach.

Not long after voicing frustration over the state of McDowell County schools, Manchin heard a rousing speech by the head of the American Federation of Teachers, Randi Weingarten, who seemed passionate about helping children escape poverty. After Weingarten’s talk, Manchin approached the union head hoping to pick her brain about what could be done. She told Weingarten that she wanted to put together a coalition that improved schools by extending its effort far beyond the schoolhouse.

“She looked at me like I was a crazy woman,” Manchin said, remembering the conversation and how the project quickly snowballed afterward.

Manchin wanted a national partner such as the American Federation of Teachers because she thought it would lend credibility to the effort. It also would provide a megaphone for national exposure if the push were to miraculously succeed, she thought.

Fixing schools in McDowell County meant thinking with community members about economic development, birth control, transportation, employment aid and adult education, as well as literacy, technical skills development and college readiness, she argued before the Board of Education with the help of Brown, the state union representative.

“I sold this to a lot of politicians by saying (poverty is a problem for) McDowell County today, but it could be them tomorrow,” said Brown. “My kids and their kids were doing well in the Charleston area, but we have an obligation to make sure these kids have a future, too.”

A photo from the 1950s show a much more populated McDowell County.

And after getting buy-in from the Board of Education, Manchin turned to corporations, in particular energy companies, for funding.

“This area is devastated by the lack of work in an industry that has made people very wealthy,” she said she told the heads of energy corporations before telling them it was time for them to give back.

Some in education thought the only way to secure support for poor children was to argue that helping them made business sense, but Manchin didn’t waste her time. She didn’t want to work alongside people who couldn’t see the moral imperative. Self-interested parties were the ones who tanked well-meaning and ambitious efforts.

It could take decades for the numbers to turn, she told each partner she pursued, and McDowell County didn’t need another empty promise.

“It didn’t get this bad overnight. The county was going on its fourth generation on welfare. No single program would turn that around,” she said. “I hoped to find people who weren’t in it for money, power, positions or stepping stones.”

By the time she headed down to McDowell County with Weingarten and the AFT’s offer of aid, she had more than 40 nonprofit, government and private partners signed on.

“You can talk politics, but it really comes back to people,” she said. “I look at young mothers who have no one and nothing. They don’t have the first idea how to be good parents and have no one to talk to and no one to call for help when their baby has cried for eight hours.”

McDowell County needed help, she said, but anyone going into the county needed to know the people there deserved respect, too.

“It’s so rugged and isolated and far removed from the 21st century, and yet these are people who love life. They love that land, and they love their families,” she said. “They just needed a little support.”

There were plenty of academics who offered answers to the problem of poverty and suggested leadership steps they believed would work to control outcomes, but offering prescriptions to poverty thought up in classrooms and boardrooms wouldn’t fly in southern West Virginia, the two women acknowledged.

“We are acting on our values in McDowell County,” said Weingarten. “The folks from Harvard and the folks from Vanderbilt, they are smart. They are very smart. But if you don’t actually engage with people and walk their walk, why would they listen?”

rown had experienced a lot before he entered into McDowell County and all its hardship in 2012, he said. Close to retirement age, he had enjoyed a successful career. He had traveled the globe, negotiated teacher contracts and orchestrated impressive legislative victories. The work in McDowell County, however, had become the most rewarding of his career, he said, and by 2016 he was beginning to believe it was the most important.

rown had experienced a lot before he entered into McDowell County and all its hardship in 2012, he said. Close to retirement age, he had enjoyed a successful career. He had traveled the globe, negotiated teacher contracts and orchestrated impressive legislative victories. The work in McDowell County, however, had become the most rewarding of his career, he said, and by 2016 he was beginning to believe it was the most important.

One of the hallmarks of Reconnecting McDowell was a mentoring program, funded through a grant from AT&T, that paired professionals with juniors in the local high schools and paid for students to travel to both the state and national capitals. There weren’t enough middle-class residents in the county to provide mentors locally, Brown said. So out-of-towners stepped up to the plate when he and Manchin asked.

While the mentors couldn’t connect face-to-face with students very often, they stayed in touch through phone calls, texts and scheduled Skype conversations made possible when another grant expanded Internet access and provided laptop computers.

On one of the trips to Washington, D.C., with students, Brown, who is one of the mentors, said he noticed one of the young men break off from the group to ride up and down an escalator. The union leader asked him why he kept jumping on and off.

“I have never been on an escalator before,” the student told him, brimming with joy.

Over the years, when Brown had trained young union leaders, he had warned them about the intoxicating nature of politics. Being on a first-name basis with people in power can go to a person’s head and twist and corrupt their thinking over time, he said.

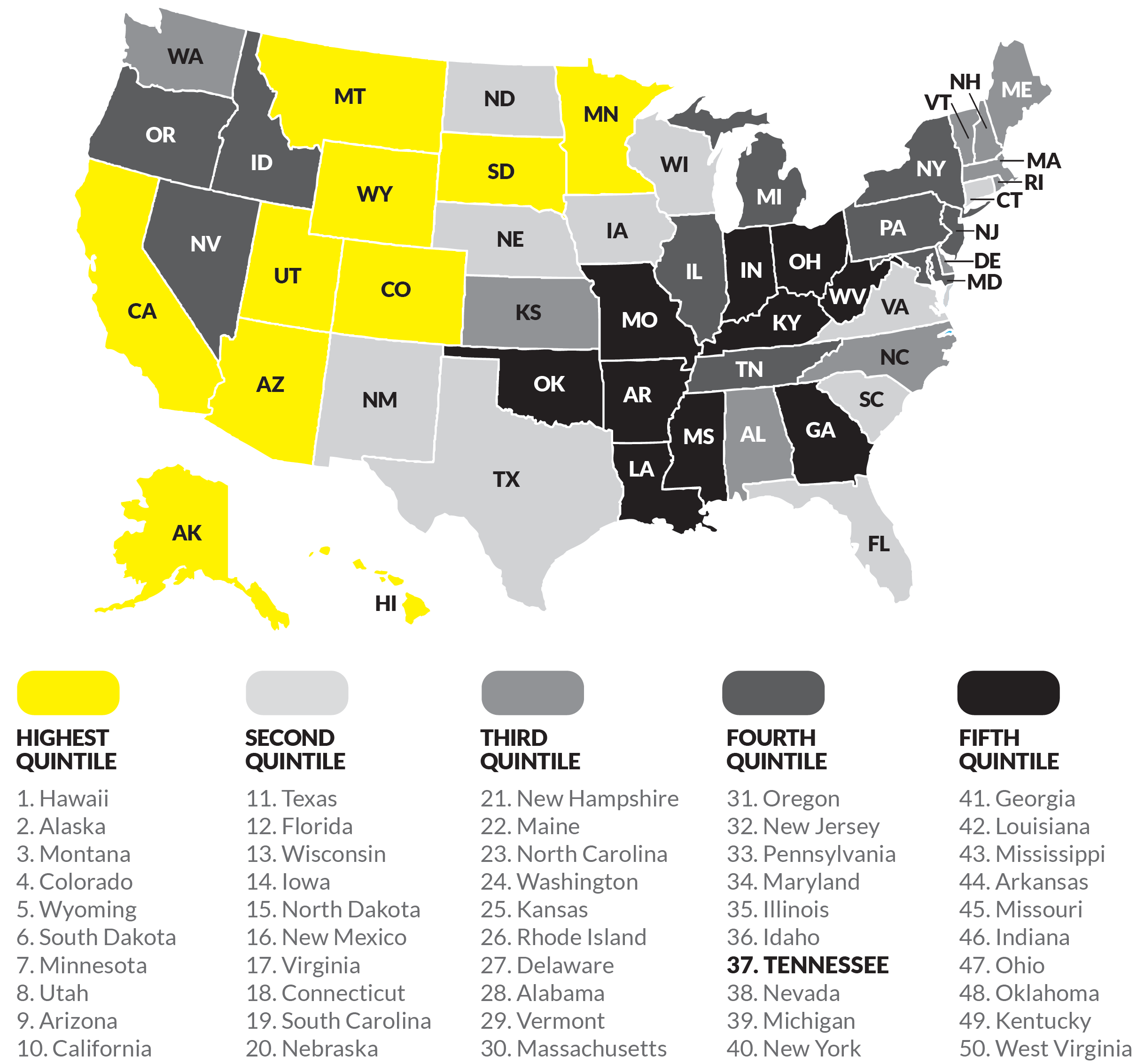

Source: Gallup-Healthways Well-Being Index

Strangely, though, McDowell County had taught him that living out of compassion and altruism felt even better than achieving power, and there was even research that showed giving was better than receiving.

A compassionate attitude can greatly reduce the distress people feel in difficult situations and can become a profound personal resource in times of stress, according to the Stanford University School of Medicine, which includes a division that researches compassion and altruism.

“I underestimated what this would do to me and what these kids would do to me,” he said. “I love them like they were my own kids. We hug and we email and we Facetime and we tweet.”

He had become jaded, he said, and didn’t appreciate the advantages he had enjoyed for so long. The children he met were glad to receive any piece of knowledge or attention. Even a ride on an escalator lifted their spirits.

“They are so full of awe over things we take for granted,” he said. “This has been almost like a religious experience. It is the most incredible thing that I have ever done.”

econnecting McDowell has yet to move the needle on poverty and test scores, but there are many signs that make those who have worked so hard for four years confident that they remain on the right track.

econnecting McDowell has yet to move the needle on poverty and test scores, but there are many signs that make those who have worked so hard for four years confident that they remain on the right track.

“They see a connection to the outside,” said Weingarten. “We haven’t come in to tell or dictate anything to the community. We respect so much that these people have had a really tough go of it. West Virginians are very proud and wonderfully resilient folks.”

In 2013, just a year after Reconnecting McDowell began, the state Board of Education announced it was coming to the county to hold its monthly meeting. Weingarten traveled 11 hours through the night from Philadelphia to get to the county in time for the morning meeting.

After more than a decade of state control, the board of education had made a decision, they told a crowd of hundreds. McDowell County would regain control of its schools, they said, thanks to the connections being built by the local effort. The entire room erupted in cheers and a standing ovation.

“It was incredible,” Brown said, thinking back.

The group plans to break ground on the teacher village this month, and many expect to see locals gathered around to watch when the machines begin to move. The schools are slowly moving toward improvement, too, Brown said.

A recent accreditation review offered exciting news as well. This year the graduation rate was up for the first time in many years, and absenteeism was down for the first time in several years. Other data showed a drop in teen pregnancy for the first time in years.

“There is still a lot of work to be done,” Brown added. “These little small victories are what keeps me getting up early in the morning.”

The most obvious signs of change, however, were in the lives of people the effort had touched.

Olivia Vaughn walks past trailers in her neighborhood of Hemphill.

Olivia Vaughn spent her entire life in a double-wide trailer in Hemphill just past the county hospital where she was raised by her grandmother, a registered nurse. She had just about given up on school when Reconnecting McDowell arrived on the scene her junior year.

So many teachers and principals had come and gone, and most students at her high school, Mount View, felt forgotten and dismissed.

“People think we are a bunch of hillbillies,” she said.

But those involved with Reconnecting McDowell didn’t dwell on the community’s weaknesses, she said. They looked to celebrate its strengths and build on them.

Just as she was about to check out of academic life, she said, a teacher asked her if she wanted to be part of the mentoring program offered through Reconnecting McDowell, and she agreed.

Then, when funds were donated so every student was able to travel with their classmates to both the state and national capitals, all expenses paid, she jumped at the chance. Children who grew up in “The Patch” — a nickname many students have for their hometown — rarely left the county and knew little about what lay beyond its borders.

Olivia Vaughn, who participated in the first year of Reconnecting McDowell’s program before she graduated from high school, right, talks with her grandmother Laura in their double-wide trailer in Hemphill. Vaughn’s father died when she was 9 and her mother left, so, like many children in the county, she was raised by her grandmother.

Vaughn said what she discovered on the outside was life-altering.

She went on tours that taught her about government. She met the governor with her classmates and was delighted when he was kind enough to hug them all and pose for photographs.

If the goal was to show students they didn’t have to conform to the picture painted by McDowell County statistics, it worked, she said.

“I think about that now,” she said. “What would my life be like if I hadn’t gone on that trip?”

When she came home and headed into her senior year, she turned her disappointing grades into straight A’s. It didn’t resuscitate her GPA or generate impressive college admission test scores, but it did put her on a path to stability. In February, she was signed up to enter a two-year nursing program and intended to pay part of her way with a job at the only McDonald’s in town.

“I like to help people, and that trip made me think that I could do anything I wanted to do. It made me think about being a nurse,” she said.

Students from McDowell County often internalized what the world said about “The Patch.” If it was among the worst places in America, then what did that make her?

But the people who met them in Charleston and Washington, D.C., seemed to care about what they had to say. Senators asked her how she would improve West Virginia and McDowell County. She couldn’t believe someone would actually want to know her opinion.

Like many, Vaughn’s parents had abandoned her as a child, leaving her with an uncertainty that made it hard to trust or believe something good was possible.

“I had seen people try to help,” she said. “But I told myself, if my mom could leave me, then anyone could leave me.”

So the genuine interest she saw in the eyes of the people she met through Reconnecting McDowell sparked confidence she hadn’t known before.

“It made me feel pride,” she said. “It made me feel like my words mattered.”