onya Rooks tugged at the bottom hem of her red sweater dress and carefully covered her bouncing right knee as she waited in the lobby of a homeless shelter in Highland Park.

onya Rooks tugged at the bottom hem of her red sweater dress and carefully covered her bouncing right knee as she waited in the lobby of a homeless shelter in Highland Park.

It was just before Christmas, and she expected a tough crowd that night. As she dabbed at the sweat on the back of her neck with a tissue, she prayed — in Jesus’ name — for help.

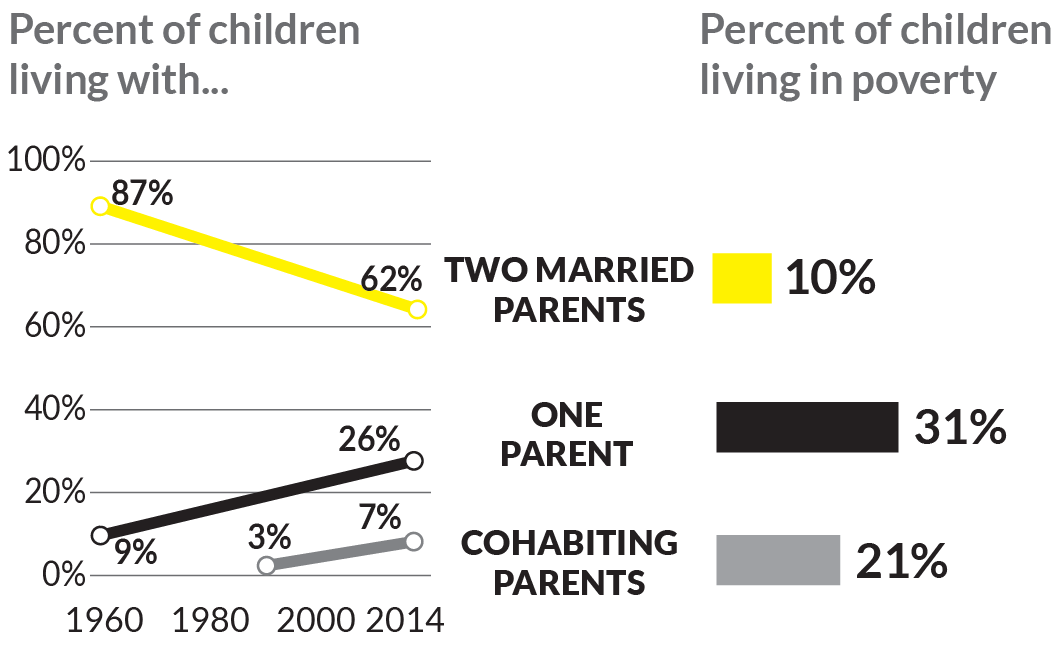

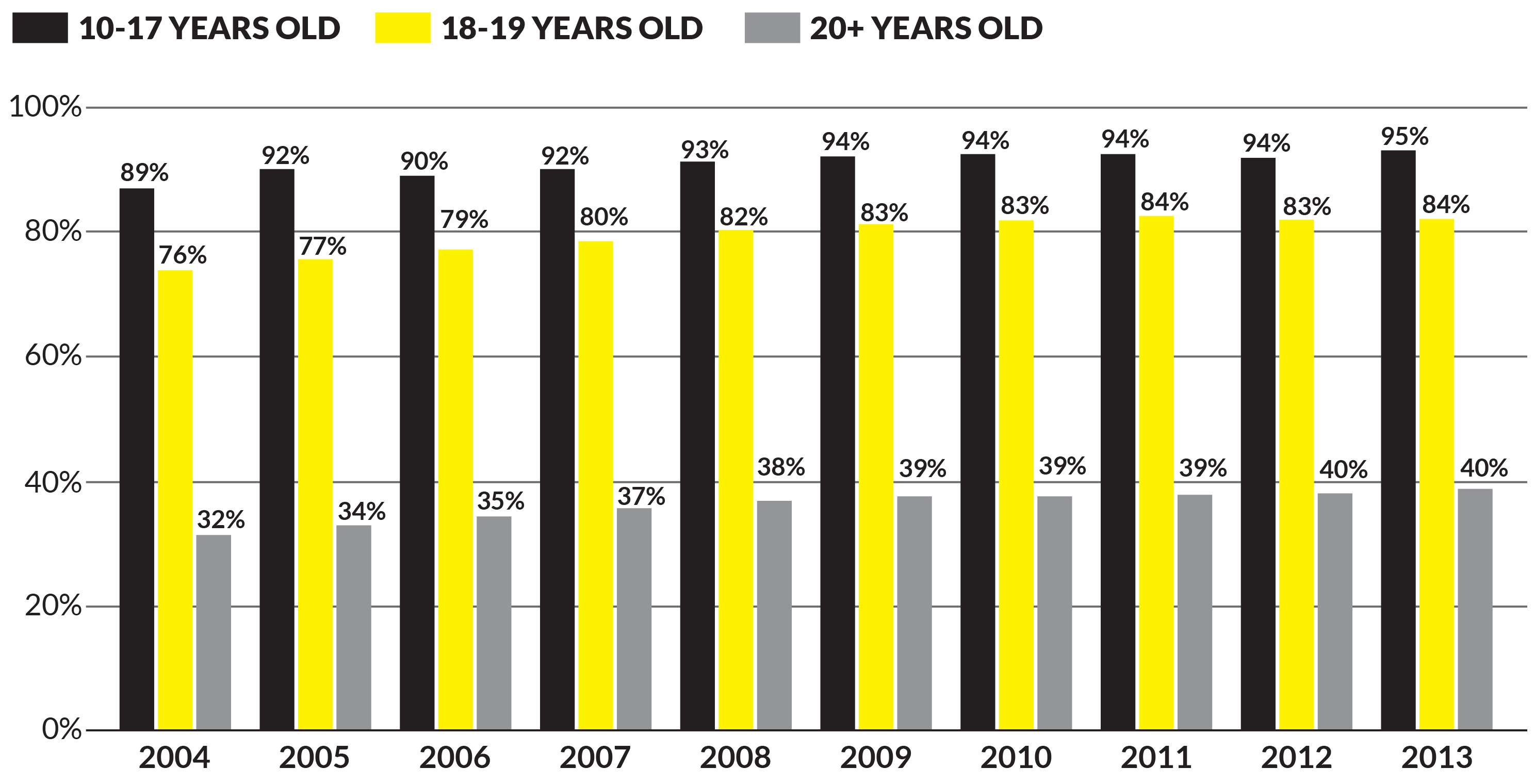

In Hamilton County 43 percent of children were born to unwed mothers in 2013, and, nationally the share was roughly the same. The trend was driving poverty in places like Chattanooga, and Rooks was just one of many people working on the front lines to reverse it.

Her tack was different than most, though.

While nonprofits worried about fliers, food boxes, classes, health insurance, housing, education, birth control and the money to fund it all, Rooks worried about the ground game. Boots on the ground, she often said, was how the War on Poverty would be won.

Note: Based on children under 18. Data regarding cohabitation not available prior to 1990; in earlier years, cohabiting parents are included in “one parent.” Source: Pew Research Center analysis of 1960-2000 decennial census, 2010 and 2014 American Community Survey and 2014 Current Population Survey

It took elbow grease and a willingness to enter into the constellation of lower-income neighborhoods that were scattered throughout the city — the places most middle-class people were scared to go.

For some local nonprofits, Rooks stepped in to do the heavy lifting. Thanks to lessons learned from her own years living below the poverty line, she had a way with struggling people, many realized. So organizations paid her to deliver their messages, and one of those assignments had brought her to Chattanooga Room in the Inn.

But she rarely stuck to the script she was paid to deliver. Those who sat on the city’s nonprofit boards couldn’t understand why some services went unused, but Rooks did. A lot of people in the inner city didn’t think nonprofits helped at all, she said. Most who enrolled in classes to improve their employability left without the social connections to make their new skills worth the trouble, the poor explained to Rooks. Single, expectant mothers were offered free birth control, free prenatal care and free parenting classes, but received little support from nonprofits once their babies were born.

Chattanooga offered the poor a lot, but it almost never offered what the poor really needed, Rooks said.

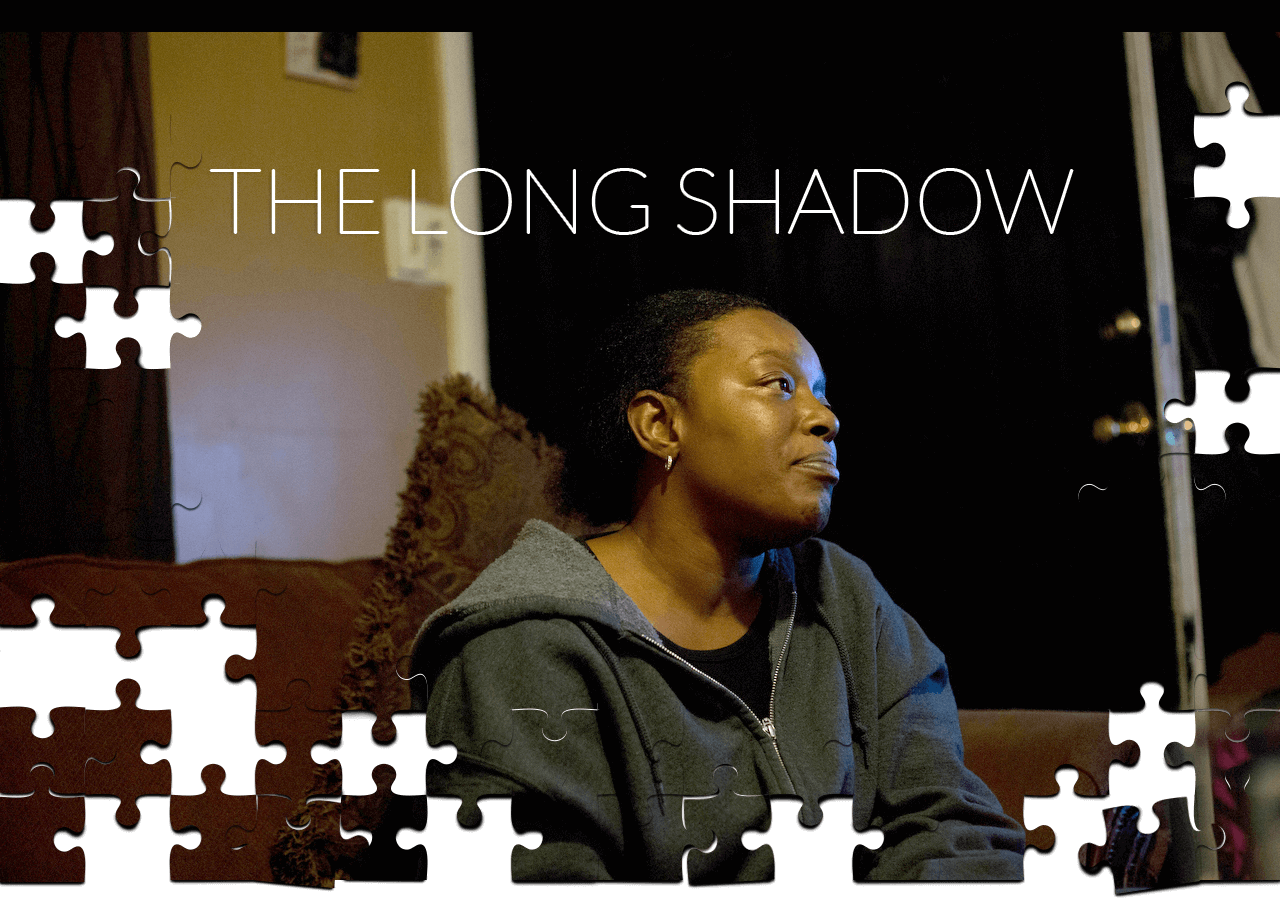

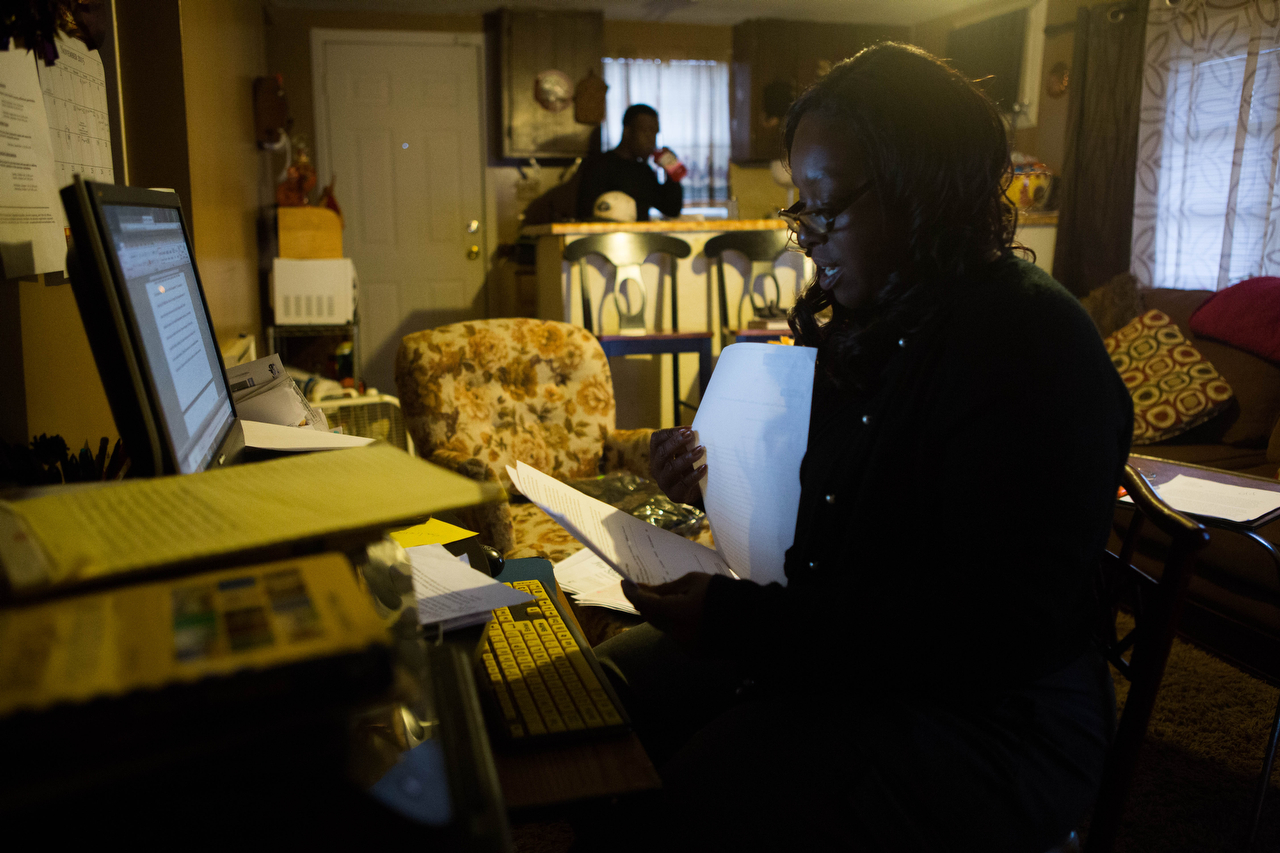

Tonya Rooks talks to clients at Chattanooga Room in the Inn, a homeless shelter for women and children, about the benefits of family planning and the services offered by A Step Ahead, which provides long-term birth control for women who cannot afford it otherwise.

As Rooks waited to speak to the women that night, she listened to a shelter staff member wind through a list of stern reminders: Too many women were going braless in dirty sweats for prolonged periods of time at the shelter, and that had to end, the staff member warned, talking over the sound of screaming children down the hall. Languishing in bed and asking children to complete adult chores was also a no-no, the shelter staffer reminded them.

“Don’t smoke in the front (of the shelter),” the staff member added before explaining how some donors might object to helping single mothers who buy cigarettes when they can’t afford diapers.

When the poor seemed immovable, tough love was often the knee-jerk reaction, Rooks had come to learn.

The poor needed to make amends and prove themselves, many seemed to say. To Rooks, though, the poor were the ones who deserved a show of good faith, as well as a real hand up. Life wasn’t always fair, Rooks agreed, and choices had consequences. But tough love, she had discovered, rarely generated much momentum once despair had set in.

“I know what you are thinking,” she told the women after giving a talk about community services. “I remember sitting at a shelter, listening to people tell me I needed to do this and that, and thinking, ‘I don’t need this.’”

She knew what it was like to feel paralyzed, she explained. She knew what it was like to lose hope.

Chaotic and lonely childhoods cast long shadows and decades of isolation eroded community, families and trust, she said; and help, if it came at all, often arrived too late to do much good.

But even if their hard work had yet to translate to success, and even if the judgment poured out on the poor and their children felt cruel and seeded bitterness they couldn’t ignore, they had to keep rolling the dice, she told them.

“I rent a house now. I have a car. I have a job.”

Hope can come unexpectedly, she said, if eyes are open to see.

he promise of the American dream is upheld by a belief that there are no odds a good-hearted and hard-working child can’t overcome.

he promise of the American dream is upheld by a belief that there are no odds a good-hearted and hard-working child can’t overcome.

Presidents rose from one-bedroom cabins, history teaches. High school dropouts, who began with nothing, sometimes died billionaires. Orphans and homeless people climbed to the top of industry.

“Luck is the dividend of sweat,” said Ray Kroc, the son of Czech immigrants who bought the first McDonald’s restaurant franchise and made it into a global fast-food company. “The more you sweat, the luckier you get.”

But circumstances do matter, academics now know.

Parenting matters. Segregation matters. School quality matters. Community bonds matter. ZIP codes matter.

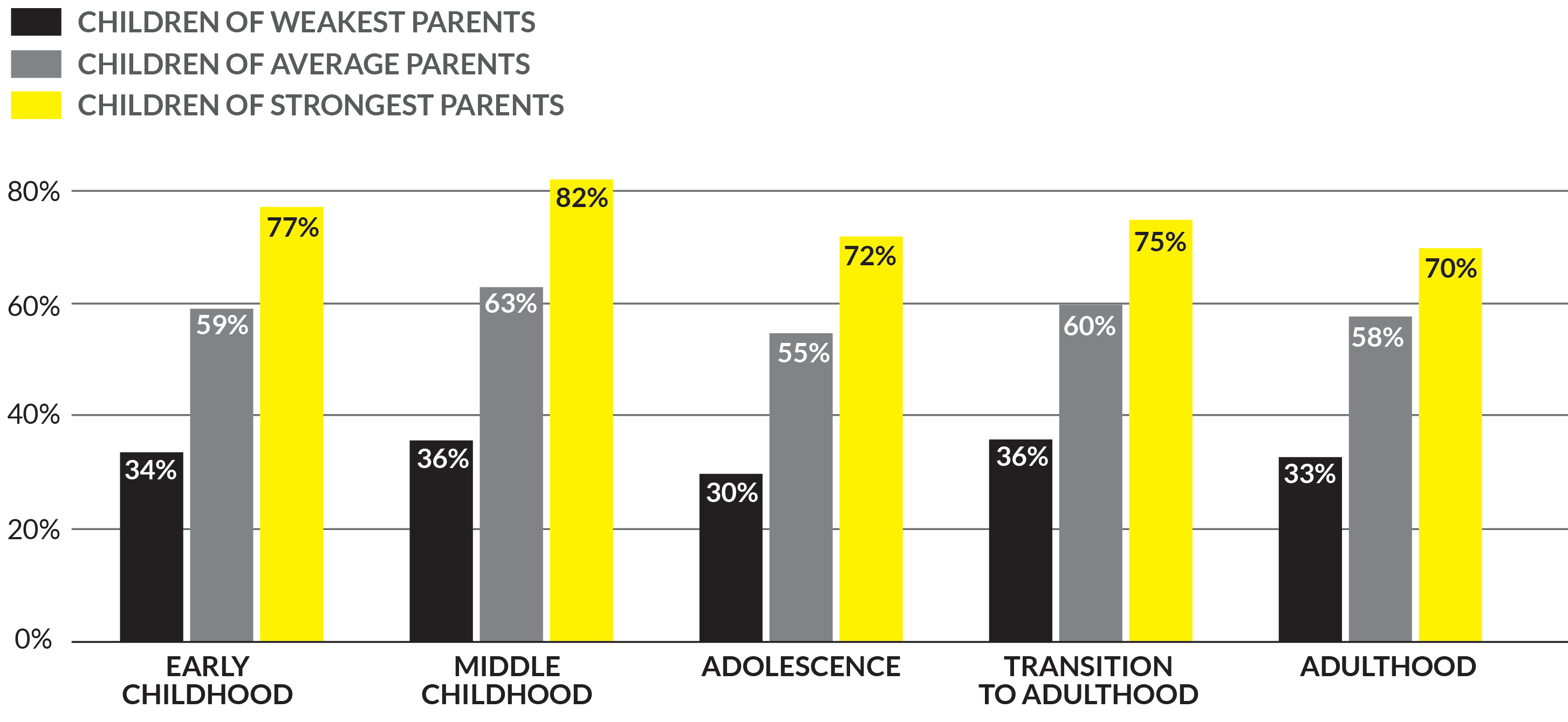

Children are shaped by families, but families are shaped by environments, research has proven.

Source: Equality of Opportunity Project by Harvard University, a data analysis by the Times Free Press.

Middle and upper-class parents believe in the brain’s plasticity, and that genes, like clay, can be molded during early childhood and beyond. That is why so many pay for expensive day care, private schooling, tutoring and other things they deem enriching. That is why so many move their families into suburban neighborhoods with good schools. They want their children to be influenced by high achievers and leverage relationships. They also want their children to feel safe.

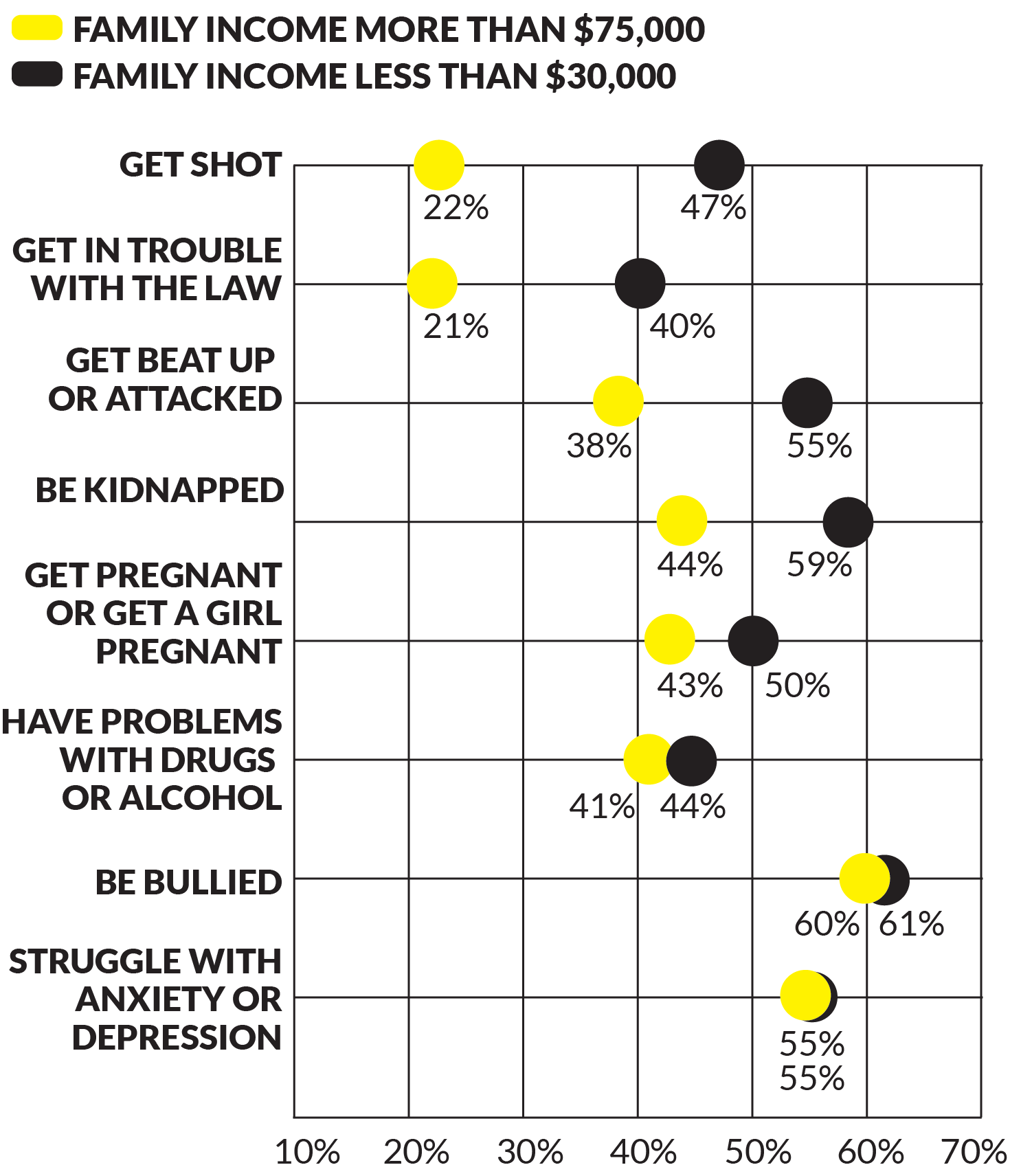

The big problem for Chattanooga, though, is that too many local children aren’t growing up to feel safe, nurtured, supported and connected, and their isolation is causing poverty to snowball, research showed.

Many frustrated with the poor want struggling parents to wise up, make better choices and whip their kids into shape, but it isn’t that simple, research explained. Of course, strong parenting was one of the most powerful ways to right the course of a child’s life, but strong parenting skills didn’t materialize out of thin air, experts said.

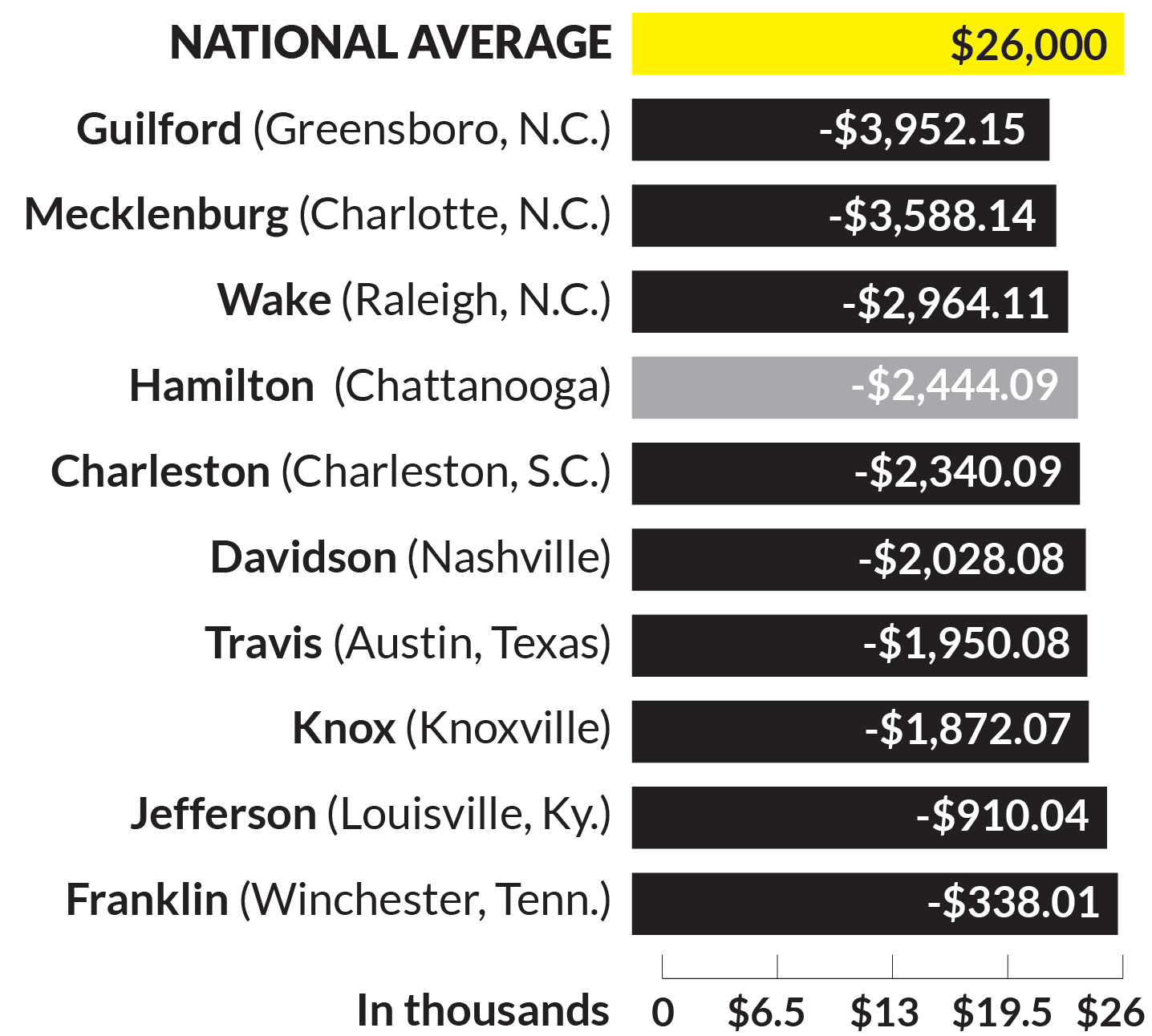

Strong parents and strong families are the results of strong communities, according to a groundbreaking study published in 2015 by Harvard University. And, according to the study, Hamilton County doesn’t really have a culture of supporting struggling families or bolstering disadvantaged children. In fact, poor children in Chattanooga would be better off financially as adults if they had been born in almost any other county in America, according to the study, which used decades’ worth of anonymous tax data to show how a child’s hometown can hurt or help their chances of making decent wages or getting married.

For example, if a poor child were to grow up in Hamilton County, instead of an average place, he or she would make $2,444.09 less than their peers elsewhere in America at age 26. The loss for children in average-income families is around $1,000. The average level of household income for Americans at that age is $26,000.

Yet, the children of the rich gain $364 by growing up in Hamilton County, compared with their peers in the average American county. A New York Times analysis of the data shows, as well, that Hamilton County is one of the best places in the country for the sons of the top 1 percent to grow up. By age 26, they earn $2,740 more than the children of the very wealthy in the average place.

Race plays a role, the researchers said. However, communities that isolate blacks isolate poor whites and Hispanics, as well.

Many researchers predict some form of political, social or economic upheaval if Chattanooga’s rich kept getting richer, its poor continued to multiply and the middle-class shrank even further.

The birth rate among poor, single women has grown, while the birth rate among more educated single women is down, data showed, and it meant that the local burden of childhood poverty wouldn’t be going away any time soon.

Still, change won’t come from Washington, D.C., or from the pundits who drive the 24-hour news cycle, experts say.

“When the stork drops a child into his or her new home, the location of that drop will affect fundamentally the child’s risk of facing poverty or segregation or experiencing reduced opportunities for mobility,” a 2015 Stanford University report on poverty and inequality states.

The economic mobility of local children is a local fight, they argue. It is a battle won or lost, in part, by the daily decisions of women just like the ones sitting around the table at the Room in the Inn that night in December.

It is a battle won or lost by women just like Tonya Rooks.

ooks spent her early childhood in a well-kept, predominantly white, middle-class neighborhood in Brainerd.

ooks spent her early childhood in a well-kept, predominantly white, middle-class neighborhood in Brainerd.

It was a middle-class life her single mother, Mary, scraped and clawed to get for her children. It was also a success story that defied the welfare-seeking mother narrative used by conservatives to argue against President Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty for more than 50 years.

In 1965, Daniel Patrick Moynihan, a sociologist later elected to the U.S. Senate, stirred controversy when he published his infamous report, “The Negro Family: The Case for National Action.”

He predicted African-American women, emboldened by welfare, would abandon marriage for their economic independence and that their children would suffer because of it. When Moynihan wrote the paper, the rising share of single black mothers had already coincided with some troubling statistics among black youth.

In response, some argued that African-Americans had been trampled on for centuries. Suggesting that black parents were to blame for their children’s lower levels of achievement seemed a convenient excuse for the South, which had systematically denied African-Americans basic economic and educational rights, his opponents said. “Blaming the victim,” a phrase often repeated throughout the culture wars, was coined by a social scientist who wrote a book in response to Moynihan.

But Moynihan gave voice to another fury, too.

Southerners, especially those who considered themselves evangelical, had come to resent academia. Many resented being told that their faith was fiction. Many who had fought to stay married and sacrificed to provide for their children didn’t want to hear about sexual freedom and that it was fine to do whatever made them happy. Children needed married parents, they said.

In Chattanooga at least, reality was far more complicated.

Rooks’ mother, Mary, hated the idea of staying on welfare and certainly didn’t get pregnant because she wanted to be on the government dole. She had grown up in the public housing projects adjacent to Howard School in the 1960s, and all she ever thought about was getting out.

Rooks’ grandparents, who had been denied rights as children and adults simply because they were black in the South, were not married. Her grandfather traveled with a gospel group, and her grandmother, who was often ill, died not long after Rooks’ mother had her first baby at age 15.

Mary Rooks had nothing in terms of money, Tonya Rooks said, but she was smart.

Mary Rooks excelled in high school at Howard, and when she graduated she was at the top of her class and college ready, her daughter said. By then, she also had three children — Tonya being the baby.

The single mother had her eye on working in the medical field, not a fairy-tale romance, Tonya Rooks said. Nursing was a surefire way to earn enough money to buy a house and make a modest living for her children in the new Chattanooga where blacks and whites were beginning to coexist in the same schools and neighborhoods. Financial stability and independence was her ultimate goal. She didn’t have time to wait for a capable male breadwinner to come around. At the time, most black men in Chattanooga were still suffering from the scourge of racial discrimination.

Source: Tennessee Department of Health, Division of Policy, Planning and Assessment.

But to provide materially, Mary Rooks couldn’t give her children much of her time, either.

Working on her nursing degree, she would flit in and out, often leaving the children with neighbors willing to babysit. Mary Rooks didn’t talk about her childhood or about how the rhetoric of feminism, free love and civil rights, which hit a fever pitch just as she was coming of age, shaped her thinking on marriage and family.

She always focused on moving forward, Tonya Rooks said.

After they left public housing and moved to Brainerd, which was still a collection of traditionally white neighborhoods, Mary Rooks held down a full-time job at Moccasin Bend Mental Health Institute, along with a part-time job at the Vance Road Women’s Clinic, just to make sure she could pay the bills.

So, when Tonya Rooks started her first menstrual period or was bullied at school, she leaned on her older sister, who fed her, tucked her into bed at night and made sure her hair and clothes were right for school every day.

Source: Equality of Opportunity Project by Harvard University and University of California at Berkeley.

They lived a comfortable life, but an anxious one, too, Tonya Rooks said. Although their mother wasn’t around much to monitor or guide them, she had high expectations. If they didn’t look busy, Mary Rooks would often force the children to read the encyclopedia aloud and write reports on different entries. They certainly never dared to make a noise while she was sleeping, Rooks said.

“We read lips because we were so afraid,” she said.

Rooks said tensions in the house came to a head once she reached adolescence. She started smoking cigarettes, she said, and began running away whenever she feared her mother’s rebuke for a bad grade or minor misstep. Eventually, she missed so many school days that she was forced to take the GED to graduate with her class at Brainerd High School.

When she drove out of Chattanooga and toward Nashville to start her first year of college at Tennessee State University, she left not knowing how much her mother’s independent spirit has grafted to her own heart.

t college, Rooks did well.

t college, Rooks did well.

Like her mother, she easily blended into a middle-class professional world.

In her medical records administration class, she earned B’s. At the state capitol, she took a work-study position helping state lawmakers craft a new seatbelt law.

Replacing her intrauterine device, a form of long-term, reversible birth control known as an IUD, was on her to-do list. The device had expired and been removed before she left for college, but getting a new one was not a priority.

She hadn’t expected to meet the nice guy she started dating her freshman year or to have sex with him. She hadn’t expected the positive pregnancy test, or the severe sickness that washed over her during her first trimester and left her too ill to eat anything but canned corn, much less study and attend class.

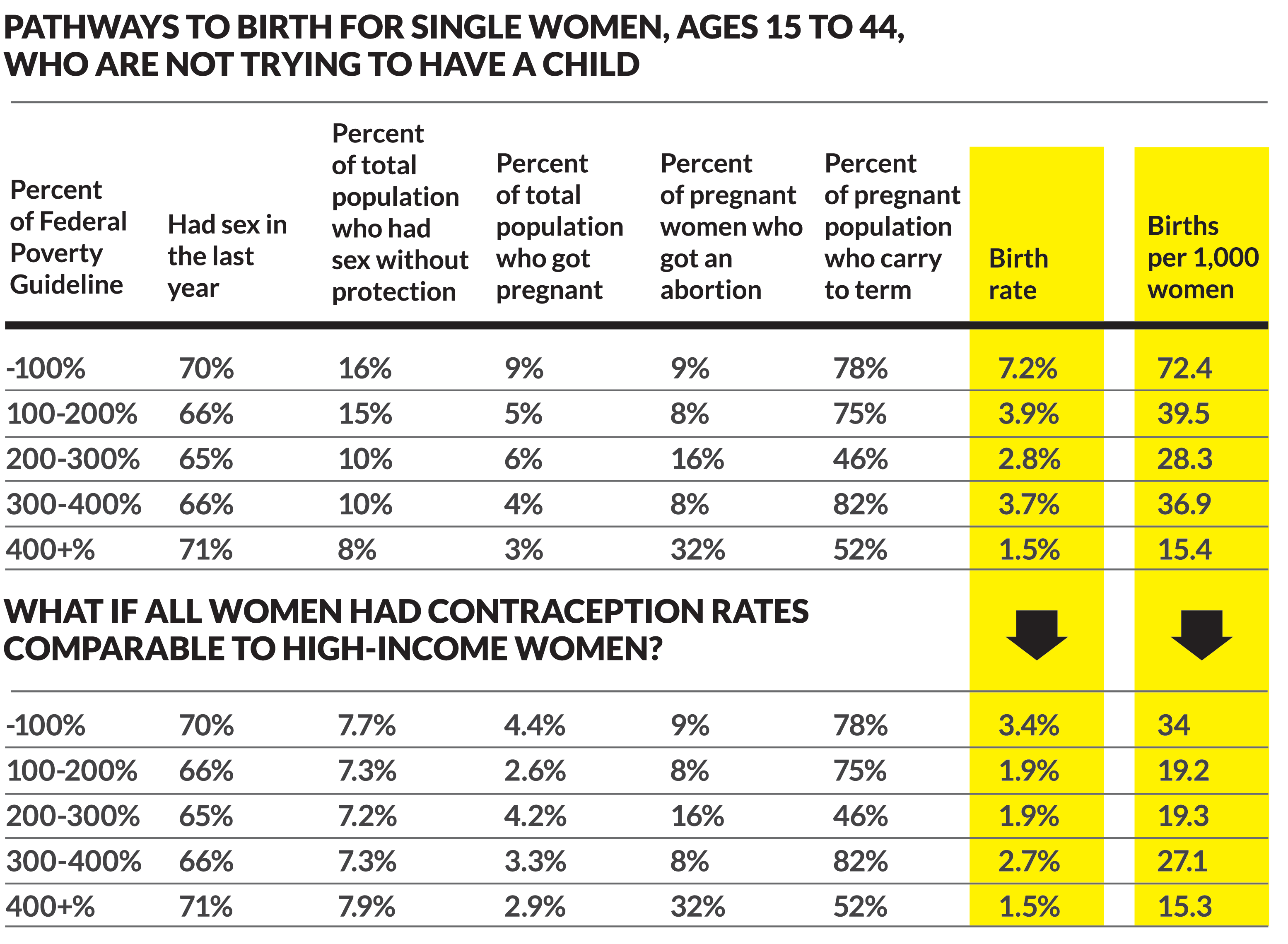

Daughters of single mothers became single mothers at higher rates than women raised by married couples, statistics have shown, but researchers had struggled to understand why. What was clear, though, according to multiple studies, was that almost all women had sex before marriage. Women such as Rooks were just more likely to get pregnant from it. They were also more likely to keep their baby.

Hoping to rebound and stay in school, even with a newborn, Rooks stayed in her Nashville apartment until she became so thin and frail from sickness that she was forced to drop out of school and return home.

“I was heartbroken,” she said, remembering the drive back from Nashville.

Source: Brookings Institute, 2016 study of sex, birth control and poverty

Marriage, to Rooks, was a holy and beautiful institution, but she didn’t pursue a relationship with the father of her first child, whom she would name Jonathan. Neither of the college students knew each other well enough to commit to starting a life together, she reasoned. Instead, she returned to her mother’s austere independence. She buckled down.

Many women who came from either turbulent childhoods or poverty and found themselves faced with an unintended pregnancy felt much the same way, research had found.

After interviewing hundreds of low-income single mothers, Johns Hopkins University sociologist Kathryn Edin concluded that many struggling women she spoke with expressed similar feelings about marriage and children. Poor single mothers held marriage in high regard, she wrote in her book “Promises I Can Keep,” but they viewed it as an unattainable goal. Marriage was for people with college degrees and home mortgages and enough money squirreled away for a modest wedding, they said.

It wasn’t viewed as a pathway to stability for them and their children; it was considered their reward. And divorce, Edin wrote, was a greater transgression to them than having a child outside of marriage.

Yet, this flew in the face of what many believed about women like Rooks.

While she hadn’t wanted to end up pregnant or poor, she played the cards she was dealt. She got a job at Brock Candy Co. and scraped enough money together to get into a modest apartment in Chattanooga. Her goal was to return to college in Nashville.

But her success was, again, short-lived.

Source: Brookings Institute

At the time, Rooks didn’t notice the change in her thinking or outlook. She told herself the dream of college and stability wasn’t lost. So she saw no risk in snorting some powder one day when a friend offered her the brief escape. But drugs relieved the pain and depression lying beneath the surface. It led to careless behavior as well, she said.

When she got pregnant with her second son, Terrance, she stopped using drugs for the safety of the baby, but returned to them after his birth. Then, for years, as her sons grew into men, she cycled in and out of addiction and poverty.

(Top) Tonya Rooks greets her older son, Jonathan, right, and his children as they stop by for a visit in January.

(Bottom) Tonya Rooks’ oldest son, Jonathan, seated, has four children: Makia, Jamelia, Jaquez and Javari, clockwise from left.

“My kids kept me going, but the streets pulled on me, too,” she said.

The ups and downs left their marks. At one point her addiction got so bad that she asked her aunt to take her children for their own safety. She started shoplifting to support her drug habit and ended up serving time in prison. With a felony record, her dreams of holding a white-collar job like her mother seemed dashed.

Still, there were people along the way, thanks to her middle-class connections in Nashville and Chattanooga, and thanks to her family, who helped her to get clean and back on a right track.

“I had a support system,” she said. “Several times, I hurt my support system.”

When she ended up in public housing at College Hill Courts for the first time in 2010, she had been working and off drugs for several years. During the height of the Great Recession, however, she was laid off and couldn’t find a new position with her criminal record and lack of college degree.

For years she went back and forth in her head about why she chose drugs and why she got pregnant.

Sometimes she would blame her mother and her childhood. Yet, mostly she blamed herself. She had a roof over her head, she told herself, water to drink, food in the refrigerator, clothes to wear and a solid education. But still she had been careless.

Infants and toddlers need far more than the basics for healthy cognitive and social development, pediatricians argue. In fact, experts know infant and early childhood stress play a role in adulthood financial stability, as well as mental health, educational achievement, addiction, criminality, pregnancy and marriage.

Children who spent their first five years in poverty had a mean income of just $17,900 between the ages of 30 and 37, showed a study published in Child Development in 2010. Among those same children, 50 percent of girls grew up to face an out-of-wedlock pregnancy. Yet, girls who spent their first years in families with incomes more than twice the poverty line saw mean earnings of $39,700 and a nonmarital birth rate of just 9 percent.

Some single mothers were strong parents with stable finances and a wealth of social connections they relied on for help. Many others, though, were not, a long-term study of family structure published by Princeton University showed.

Balancing breadwinning and parenting was a parental struggle that often made children’s lives chaotic.

Odd work hours and inflexible schedules at low-wage jobs made many women unable to nurse, hold or talk to their young children. And their absence meddled with infants’ neurological development and dopamine levels. The result, according to pediatricians and child psychologists, was often a chemical imbalance that manifested as attention deficit disorder, a lack of self-regulation, poor planning and organizational skills, as well as a tendency toward addiction.

Single-parent families were often the heads of fragile families, the groundbreaking Princeton study found, and their fragility was caused by the stress and trauma imparted by their poverty and the isolated environment they found themselves trapped in.

“Little children, they need stability,” said Sara McLanahan, a Princeton sociologist widely considered one of the nation’s leading experts on families and children and one of the authors of the study. “They need to know what to expect. … But there is a lot of emotional upheaval. Most of these children are experiencing chaos.”

So while the effects were subtle and would play out, sometimes quietly, over a lifetime, women such as Rooks rarely sailed through adulthood unscathed.

wo things eventually settled

Rooks’ lingering questions about poverty: an author named Ruby K. Payne and her return to public housing as an adult.

wo things eventually settled

Rooks’ lingering questions about poverty: an author named Ruby K. Payne and her return to public housing as an adult.

Payne, an educator, became internationally famous when she published a book in 1995 called “A Framework for Understanding Poverty,” which argued that the middle-class viewpoint of those working to alleviate poverty were often ill-suited for connecting with the poor.

She also argued, with research behind her, that class-based stereotypes that separated the poor and middle class were often built on mistaken assumptions of laziness and immorality that had no grounding in science.

The poor often appeared disorganized, forgetful and late, but that made sense, experts explained. Scarcity of resources forced a focus on daily crisis and allowed no room for long-term planning, research had shown.

The low aims of the poor were also a concern, but science explained that, too. A lifetime in poverty often robbed people of the ability to believe they could accomplish what they set out to accomplish — an internal motivator psychologists referred to as self-efficacy.

Middle-class children were able to develop self-efficacy, experts argued, because their paths were mowed for them. They often entered school prepared, had homework help and a safety net after graduation. Poor children’s first experiences, however, were often cloaked in failure. At every turn, it seemed, they heard messages that convinced them the game was rigged. So they just decided not to play, the research showed.

And they were rarely exposed to any models that could have steered them down a different path, Rooks said she noticed once she arrived in the Westside.

By the time children of fragile families reached college, it was no surprise, then, researchers said, that women such as Rooks fumbled their use of birth control. Studies had clearly linked low levels of self-efficacy with higher rates of unplanned pregnancy.

Source: Pew Research Center, 2015 Parenting in America

Reading Payne while living in the Westside helped Rooks understand that poverty wasn’t always what it seemed. Still, living beside struggling people taught her even more.

Whenever she found herself down over the years, she had grabbed the hand of a middle-class friend or family member and was able to climb her way out. That was what most middle- and upper-class people did when hard times hit, she said.

But while living in the Westside she learned that many among the poor didn’t get a hand up because people were too busy worrying about it becoming a hand out.

People will always slip in and out of situational poverty, experts note. Generational poverty, though, thrives because of community inaction, not a lack of personal initiative, Rooks came to believe. Sure, the poor had bad guys and moochers among them, but so did every social class, she said.

While living in the Westside, she met a lot of nonprofit workers who had big ideas about how to address poverty. Some told her they envisioned a high-quality day care and prekindergarten solution. If more poor children could have an early childhood education, the numbers would turn, they argued. And while some recent research had poked some holes in that, they were right to point out the need, research showed.

Others she met wanted to campaign around marriage and parenting. Healing families had to be the top priority, they said. If poor parents had relationship-building skills and better parenting skills, the tide would turn, they impressed on her. And those methods did help low-income African-American families, research had shown, although few experts saw a real return to marriage in the cards.

And years later, once she had found middle-class stability and re-entered college to complete her degree, this time in social work, some were advocating for a birth control solution to poverty, as well. A recent study in Colorado showed that making long-term, reversible birth control available to poor women had a real impact on poverty.

They were all decent ideas, Rooks thought. Still, they all missed the real fix.

Strangers with good ideas didn’t rescue people from poverty, she said. Neighbors who built trust, however, did.

Of course single mothers in poverty needed better access to child care, kindergarten, birth control and training in marriage and parenting. But even with all that and better schools, Chattanooga wouldn’t solve the poverty puzzle, Rooks knew.

Tonya Rooks works with clients at Chattanooga Room in the Inn, a homeless shelter for women and children.

It might sound silly to argue that killing poverty was as simple as building trust and sowing hope, but Rooks believed it to the very bottom of her soul.

She had lived it.

When she ended up returning to the Westside after being laid off in 2010, she had given up on everything, she said. It was a low that crippled her ability to see anything good in her future. At times, she was tempted to believe that she deserved to be where she had landed.

But she woke up from the bad dream one day, she said, when an office worker with the Chattanooga Housing Authority asked her to run for president of the project’s resident council. The woman told Rooks she had been watching her and had seen something special in the way she carried herself.

“You think I can run for president?” Rooks said, resisting at first. “The people are not going to vote for me.”

“I think you will be good,” the women told her, unfazed by Rooks’ insecurity. “You have to campaign, like you are campaigning for president of the United States.”

It took time before she could leverage the trust of Westside residents and help some launch out of the projects for good. “You make one step. I will make the other,” she promised.

It took time before she found a job at a nonprofit doing work she came to love.

And it took time before she was able to leave the Westside herself, move into a small house off Amnicola Highway and return to her dreams of a college degree and a white-collar career.

Most of all, it took time for her to forgive herself for how her choices hurt her sons.

But she shook free of poverty long before she finally made it back to the middle class, she said.

She left poverty, she now believes, the moment she decided to run for president of the Westside council.

Because what she saw in her encourager’s eyes wasn’t pity or paternalism, it was hope.