ong before

the sunrise, Tim Jones started the work of fathering. He cleared the futon of blankets and pillows, trying not to stir the 4-year-old and 9-year-old asleep on his twin bed and trundle in the living room.

ong before

the sunrise, Tim Jones started the work of fathering. He cleared the futon of blankets and pillows, trying not to stir the 4-year-old and 9-year-old asleep on his twin bed and trundle in the living room.

Jones, a 30-year-old divorced father of two, boiled water to make hot oatmeal, a nutritious and affordable breakfast that at least his baby boy, Tariq, liked.

He studied the landscape of the day. Will it rain? What will the boys wear? Did they finish their homework?

He realized Tariq didn’t have clean pants. So he dug through dirty clothes.

Once Tariq was awake, he set a place for him at the table and watched him bow his head for a silent prayer, squeezing his small fingers into one another with surprising reverence. Timothy, the older son, skipped breakfast.

Tim Jones makes oatmeal for his sons before school while Timothy, left, plays a reading game on the computer and Tariq sleeps in a pullout trundle next to Jones’ bed in his studio apartment.

Not long afterward, Jones’ cross-city morning trek began.

Jones would start by walking Timothy to the school bus stop across from the YMCA downtown. Next, he took Tariq’s hand and boarded a Market Street bus toward his prekindergarten program in Brainerd. Finally, he boarded another bus to return downtown.

In total, the whole trip would cost him nearly two hours if the buses ran late. But eventually Jones would find his way back to his day job, parking expensive cars for minimum wage.

Jones is one of Chattanooga’s working poor. With a limited education and childrearing responsibilities, his options are limited. But, in his own way, Jones is heroically rising above his circumstances, while many of his generation are not.

Employment among undereducated American men in their prime is free-falling, statistics show, creating an underclass of able-bodied males who don’t have the income stability or social capital to become good husbands and fathers. This contributes to a cycle of multigenerational poverty that has hollowed out Chattanooga’s middle class and threatens to stop economic progress dead in its tracks.

eneath the Southern

economic malaise is a powerful force often unrecognized.

eneath the Southern

economic malaise is a powerful force often unrecognized.

For decades, working-class men — those who forged America’s industrial strength and whose rugged physical commitment is romanticized in country music and regional folklore — have been battered by an identity crisis.

Falling unemployment rates have masked the fact that many men have abandoned work altogether. In fact, there has been an historic decline in the number of prime-age men in the workforce, according to a national report published last year by Stanford University.

In Tennessee, the share of prime-age working men, those between 25 and 54, tumbled from 88.2 percent in 1999 to 81.8 percent in 2014.

Few businesses remain in the market for simple, straightforward hard work. Intelligence, innovation and interpersonal skills are the prerequisites of tomorrow’s professions that were once male-dominated, say economists and social scientists.

The past nine recessions — spread between 1953 and 2008 — battered men, whose employment rates were notched down each time and never fully recovered, and sectors that employed the least-educated men were hit the hardest. Women, on the other hand, have fared better and remain on pace to recover the jobs lost during the most recent recession, the Stanford Report Card on Poverty and Inequality reports.

But at the current rate of recovery for men, it could take 12.5 to 13 years for their employment to be as robust as it was before the Great Recession. Still, the U.S. economy has never gone more than 12.5 years without a recession, the report pointed out.

“The glum assessment here is that no state has come up with a policy that might, if widely adopted, increase the rate of recovery in employment,” wrote Michael Hout, professor of sociology at New York University. “The prevailing optimism about the recent jobs and unemployment reports is in this sense misplaced.”

And this fact is currently driving the concern building among Chattanooga leaders.

Mark Davis checks the job listings in a newspaper classifieds section while searching for employment at a Tennessee Career Center in September 2015. Such career centers are located across the state to help job seekers find work.

Experts say Chattanooga is one of the few cities where good-paying jobs in manufacturing fields are increasing. But the reality is that many local residents aren’t filling those positions.

Currently, there are 15,000 jobs in Hamilton County being filled by commuters coming from outside the county because not enough local high school graduates are qualified for the positions, says a report called Chattanooga 2.0, published in December by a coalition of local business, nonprofit and education leaders.

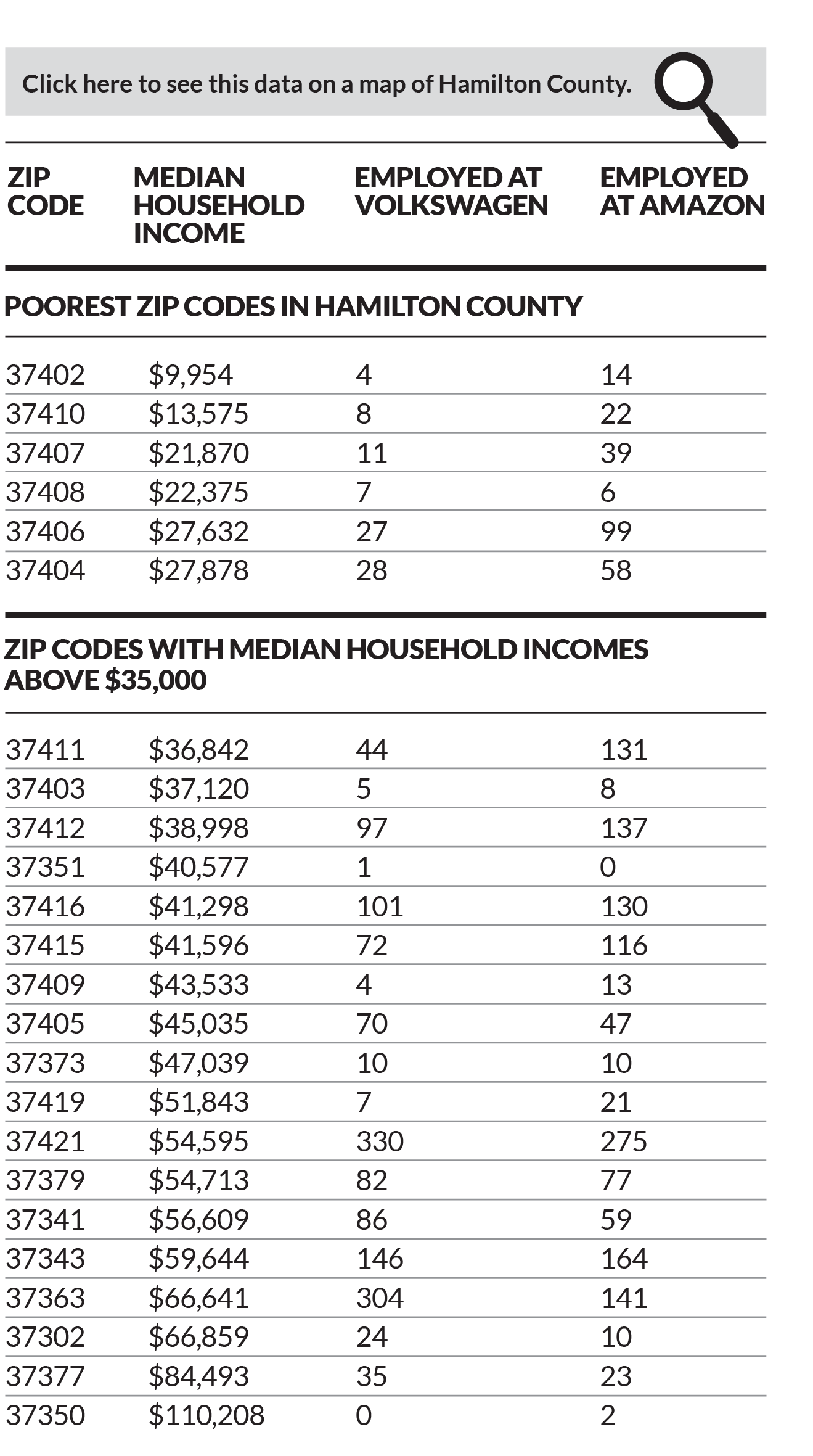

In 2008, state and local leaders heralded the rise of automotive manufacturing in Chattanooga when Volkswagen picked the city for its new $1 billion plant. Politicians wooed the automaker with roughly $577.4 million worth of tax incentives, which, at the time, was the biggest incentive package ever offered to a company by politicians in Tennessee.

But by 2014, less than two of every three employees at the Volkswagen plant were from Hamilton County. And only a few dozen of the employees came from neighborhoods in Chattanooga where the poorest men and women, with the lowest employment rates, lived, local commuting data show.

Source: Commuting data compiled by the Chattanooga Area Chamber of Commerce

Finding workers was and is surprisingly hard, said Bill Kilbride, president of the Chattanooga Area Chamber of Commerce. The chamber advertises and holds job fairs, but attendance is often sparse, he said.

Despite an impressive placement rate, Chattanooga State Community College’s technical training programs for the most in-demand fields, such as welding, aren’t full, said Jim Barrott, president of the College of Applied Technology.

Others believed that men just didn’t want to work and they had abandoned both work and family because they had lost their moral backbone.

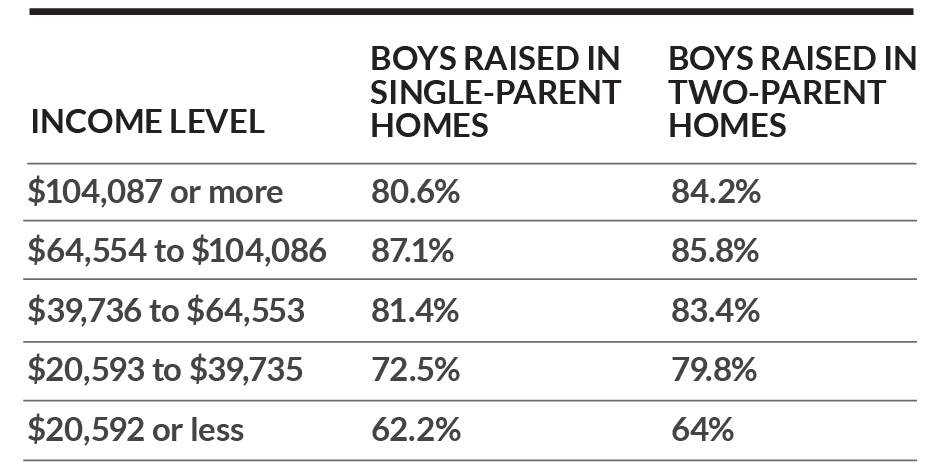

But a study released in January indicates that what is more likely affecting those men is economic segregation in neighborhoods and schools, the rise of income inequality and the rising share of single-parent homes in communities.

These days, working-class men can’t leave high school and walk into a job that pays middle-class wages. They can’t get hired at the factories their fathers or grandfathers might have worked at. Too many have closed. And the ones that are here require more skills.

So without connections to or experience with a line of work that requires academic or skills training rather than physical prowess, their pride and their earnings have suffered.

And the diminished stature of working-class men is contributing, experts say, to the recent rise in poverty and decline in marriage among families of all races. In the long run, though, their aimlessness may pose a threat to the entire region’s economic growth, some warn.

“The challenge facing us in part is how do we get our boys, teenagers and young men on an education track and a life track that gives them hope for their future,” said W. Bradford Wilcox, one of the nation’s leading experts on the topic of marriage and families and the director of the National Marriage Project at the University of Virginia.

“We are in a vicious cycle where boys who aren’t raised by their fathers don’t get the schooling or the labor force experience they need to be marriageable, and they are more than likely to repeat the process.”

ent over a canvas, Kourtney Brown traced his sketch with blue acrylic, circling with his paintbrush until the image of an alien appeared alive, in color. The alien, drawn with bulging eyes and a wide forehead, was the 19-year-old’s signature, an image he returned to when he wanted to illustrate his precarious position in the world.

ent over a canvas, Kourtney Brown traced his sketch with blue acrylic, circling with his paintbrush until the image of an alien appeared alive, in color. The alien, drawn with bulging eyes and a wide forehead, was the 19-year-old’s signature, an image he returned to when he wanted to illustrate his precarious position in the world.

In his bedroom in Avondale, a pocket neighborhood of East Chattanooga, he was working late to get ready for his first art show, a chance he thought would finally launch him into a career that could give him purpose. In the background, a song by he liked by hip-hop band NERD played on repeat.

Do you know what I am?

If you don’t see my face no more

I’m a provider, girl

One year after graduating from high school, Brown was still unclear about who he was and where he belonged.

He had attended Chattanooga School for the Arts and Sciences, a magnet school introduced to the county to accommodate a federal integration mandate, and had been exposed to wealthier children with professional parents and ambitions. Still, he was unable to leverage the school as a resource.

While he had the creative bent of his classmates, he didn’t have their resources. At home, Brown had no one to help him study. When he was down after receiving a bad grade, he didn’t know who to turn to for encouragement. If he needed to go somewhere for academic reasons, there was no one able to take him. While he languished in the inner city through the summers, other students used their breaks to connect with artists and actors at expensive camps far away, travel abroad and participate in clubs and honor societies that catered to creatives.

Kourtney Brown leaves Studio Everything on Glass Street carrying wooden boards of his old artwork, which he plans to paint over with new designs. Brown paints at the gallery and at home, hoping that he can one day make a living as an artist.

Brown’s father was in prison when he was born and stayed there until his son was just about to leave high school and enter adulthood. In fact, Brown was so disconnected from his father that he had never even learned his last name. And his mother gave him to his grandmother who gave him to his great-grandmother to rear.

His great-grandmother, Betty Jean Morgan, now 82, never thought much of Brown’s artistic ambitions. She had thought it best for him to pursue a practical profession. Young men worked with their hands when she had been a young woman, but she knew college had become the ticket for the modern man.

He also felt another kind of pressure from the boys in his neighborhood who sold drugs, joined gangs and resorted to violence to feel respected.

Yet, the larger message he heard from the outside world was that he had no shot at success at all. Statistics about boys, especially minority boys, showed their test scores, graduation rates, earnings and life expectancy were among the lowest of any demographic group in the country, while their incarceration rates were among the highest.

Ken Chilton, a professor at Tennessee State University who has studied the city’s racial gaps at length, offered a chilling example last year to the NAACP. If 100 black male ninth-graders in Hamilton County were followed all the way through their schooling, only 56 would end up graduating from high school, he said statistics showed. Then, only around 23 of those graduates would enroll in a training program or college. And by 2018, only five men would have college diplomas or degrees.

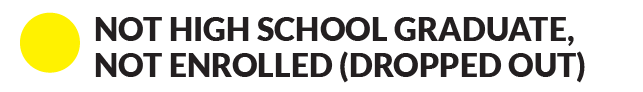

Source: U.S. Census Bureau

Statistically, young black men still continue to struggle the most in school and in the labor force, David Autor, an economist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, states in a report titled ”Wayward Sons.” But the report found the struggle to adapt to the economy is growing among men of all races.

This was a situation created by education deficits and a deterioration of opportunities for unskilled men, he said, but it was a situation created by a fathering deficit, too.

Social science research showed that dads played a key role in preventing poverty. Boys raised by single mothers without their father were at an increased risk of substance abuse, risky behavior and poorer school performance, research showed.

Scientists were still teasing out why. Some research has shown that absent fathers hindered proper brain development. Yet, a Georgetown University researcher’s analysis of data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics showed that childhood poverty, not family structure, were to blame for adulthood poverty and low educational achievement.

Boys who grew up without fathers in poor neighborhoods became men who struggled in the work world, found a research paper released in January by the National Bureau of Economic Research, a nonprofit research organization. The report found much lower employment rates for boys than girls who grew up in single-parent homes in bleak environments.

Surrounded by women and without his father, Brown tried to father himself. He told himself to stay positive. He chided himself when he fell behind. He wrote himself inspirational messages.

“Find your passion in life, and let it kill you,” he wrote.

Brown loved to draw. But he never believed being an artist was possible until he skateboarded down Glass Street a year ago. In a rehabbed section of the East Chattanooga neighborhood, a nonprofit, the Glass House Collective, sought to bring art to inner-city neighborhoods by helping to open several businesses.

Riding by Studio Everything, he saw a black man working on sculptures and painting, alongside neighborhood kids there to use the studio’s resources. The sight jarred him. He had never seen a black, male professional artist, and in an instant his dream seemed so much more possible to him.

(Top photo) Kourtney Brown talks with his girlfriend, Briah Gober, at his art exhibition in a renovated space next to a collapsing building on Glass Street.

(Bottom photo) Kourtney Brown, left, gets help cutting up boards for new paintings from Studio Everything owner Rondell Crier, a local professional artist who serves as a mentor for Brown and other neighborhood artists who spend time at the studio.

He tried to write song lyrics. He painted posters at the art studio, which opens to the neighborhood twice a week. He designed his own logo to go on sweatshirts, trying to rebrand himself as an artist and an entrepreneur. All the while, his great-grandmother urged him to go to college.

Six months later, he signed up at Chattanooga State to start classes and work toward a degree in graphic design. To earn money, he drove the train at Chattanooga Zoo.

Not long after, he was invited to display his art in a gallery show on Glass Street intended to highlight unknown artists.

On the crisp October night in 2015, hundreds of people filled the new studio and walked past his paintings on display. Some, including a few friends, a former girlfriend and an old coach, stopped and took notice. One man even asked him to follow up about a piece. Brown scribbled his number on a piece of paper, but the man never called back.

Brown hoped the show would be his big leap into adulthood and toward being the respected, self-sufficient man he longed to be. But in the months that followed, without a mentor, money or connections, his dream seemed further off than ever.

Then in January, just as he was about to turn 20 years old, he took a job as a laborer hauling boxes for FedEx. It certainly wasn’t art, but he told himself to be thankful he was at least working with his hands.

He hadn’t wanted to give up on art, he assured everyone. But he was already a man, and a man had to take any work he could get. He wouldn’t look for a father figure who could teach, love or guide him anymore, he told himself.

Still, he checked his phone hoping to find calls, and when his girlfriend brought him around her family he always palled around with her dad.

He held out hope that someone, somehow, would offer him a pathway to purpose.

he men arrived in dirty jeans and steel-toe boots, some with work gloves still tucked in their back pockets. Some men came because a judge said they might avoid jail time. Others because they needed a job.

he men arrived in dirty jeans and steel-toe boots, some with work gloves still tucked in their back pockets. Some men came because a judge said they might avoid jail time. Others because they needed a job.

Todd Agne greeted each man in the conference room at the nonprofit First Things First, located downtown, as they stacked slices of Little Caesars pizza on their plates and sipped on grape and orange Fanta.

It was the fourth time the men were meeting for Agne’s “Dads Making a Difference” class, which claimed to stabilize troubled men. These men owed thousands of dollars in child support. Many had already been to jail and needed steady employment. But Agne knew the solution wasn’t to push them off to a staffing agency or send them to a job fair.

Agne asked them to talk about their feelings, their likes, desires, motivations and their personalities.

Agne knew from experience that these men had been beaten down. When they thought about manhood, they often thought of the messages they were told throughout their life:

“You ain’t no good.”

“You’re never gonna be any good.”

“You’re just like your daddy.”

He found that they were constantly screamed at, demonized by the court system, haunted by juvenile records and addiction and hurt from abandonment they didn’t understand. They were also confused about what it meant to be a father and a husband.

And all the pressure, discouragement and lack of support caused men to check out of marriage, fathering and even the work world, some experts said. Social scientists have proven that men tend to shrink from responsibility when they can’t provide for their families.

William Julius Wilson, a Harvard sociologist, found a man’s earnings play a significant role in whether he will get married or will stay married. But Wilson found men aren’t necessarily the ones who want to check out of responsibility — often women see these men as less desirable marriage partners and choose not to marry them.

Persistent joblessness mixed with negative outlooks on marriage “have increased out-of-wedlock births, weakened the family structure, expanded the welfare rolls and, as a result, caused poor inner-city blacks to be even more disconnected from the job market and discouraged about their role in the labor force,” Wilson wrote in his 1996 book, “When Work Disappears.”

Source: Burning Glass, a Boston-based research firm

Twenty years later, his words sound prophetic as uncolleged men, both minority and white, can’t find work, upsetting the balance of family life.

While men still hold the elite top positions of power, women have been replacing men in jobs they traditionally held, such as managerial and finance positions, and they now dominate nearly every job projected to grow the most in the future, said journalist Hanna Rosin, who wrote the book “The End of Men.”

So when Agne came face-to-face with those men in a room, he realized that, sure, there are few who seemed to deserve the term “deadbeat.” But most of the men wanted to work hard, and often did, splitting their time between two jobs to scrape by at home. They were trapped, though.

Agne knew many of the men he worked with hadn’t been nursed or nurtured as infants because they had been raised by very stressed single mothers trying to provide for their sons with little support. And he knew that the lack of attention they received delayed them when they entered school. Their first grades were often failing ones, and when they couldn’t get help to catch up academically, the humiliation caused them stop trying.

They were playing a game for which no one had ever taught them the rules. So Agne stepped in.

He taught them they had talents and skills to offer to the workforce and they played a significant role in how their children were shaped.

hile the federal

government has funneled billions of dollars into job training programs with mixed results,

there’s a shift happening in communities driven by Harvard’s Business School call for businesses to change their posture toward at-risk populations.

hile the federal

government has funneled billions of dollars into job training programs with mixed results,

there’s a shift happening in communities driven by Harvard’s Business School call for businesses to change their posture toward at-risk populations.

Often that looks like a partnership between businesses and a community college, referred to as sector-based training, where programs are created to give workers certifications for jobs in their community. Last year, Gov. Bill Haslam heralded Chattanooga State’s technical school as a model for the state when he unveiled his plan to make training programs at state-funded schools free for anyone over 24 years old.

But training programs alone won’t bridge the gap that research shows at-risk, uneducated men, marred by poverty, single-parent homes and isolation bring into the workplace, said Harry Holzer, a Georgetown University professor of public policy who also does research for the Brookings Institution. Many don’t meet minimum education requirements to get accepted, and those who do often drop out without sufficient support services along the way.

Source: The Quality of Opportunity Project

Agne knew it took more drastic tactics that involved teaching men how to take pride in their work again by giving them a road map to overcome their own obstacles.

In his class, it often looked like this: When the men wanted to go back to school but feared failure, Agne helped them work through it. When they wanted to give up on fathering because their child’s mother couldn’t talk without screaming, he offered communication strategies. When they seemed discouraged about their criminal record, he told them to think about their past in a positive light and sell employers on what lessons their mistakes taught.

And feeling known made a difference to the men in his class. They called Agne when they buried their parents, when their children were shot and when they lost a job they desperately needed.

“What would a great man do in this situation?” he would ask them.

Approaches that use tactics similar to Agne’s are often centered on the idea of teaching people to believe in their own abilities; it’s what social scientists call building self-efficacy. Cognitive development research shows boys who approach adolescence with low self-efficacy are at risk of developing problem behaviors, perform poorly academically and lack social skills, according to “Theories of Human Development: A Comparative Approach” by Michael Green and John Piel.

But self-efficacy is developed when people accomplish difficult tasks, when they see their peers succeed, when they learn to persevere through tasks and when their options grow as they continue to succeed, according to Albert Bandura, a psychologist at Stanford University, who developed the theory of self-efficacy.

In Minneapolis in 2003, then-Mayor R.T. Rybak found a creative way to give isolated teens in poor neighborhoods the chance to gain experience in summer internships that often led to long-term employment. The students first were given the training to succeed, then sent to employers.

In those paid internships, the students weren’t asked to shadow employees, fetch coffee or work for free. Instead the positions were in a variety of professions, allowing students to explore their interests and gain real-world experience. After a decade, the program has given more than 21,000 students paid summer jobs, and many of those students have gone on to full-time employment. But several students said the most important thing they took from the experience was the confidence they needed to step out on their own.

In Chattanooga, the Public Education Foundation is mimicking Minneapolis’ program, called Step-Up, hoping to train 100 low-income teens to fill paid summer positions in their first year of the program.

Other tactics focus on students in the classroom, offering hands-on experience in work that could lead to a career.

In Nashville, the district transformed its high schools into career academies where schools push teens toward college but also work with businesses to create pathways to careers that pay well but don’t require a four-year degree. The hands-on projects are just one way students learn how to problem-solve in a field of their choice, which could include making bio-fuel, building engines, conducting mock trials in a simulated courtroom or writing and producing songs in a Grammy-designed studio.

An extensive, eight-year study showed young men benefited the most from career academies, increasing their future earnings up to 17 percent after graduation. Yet not only did men increase their earnings, they were also more likely to get married, the study found.

Source: MDRC, a nonprofit research firm tracked career academy graduates over eight years and Daniel Schneider explored the findings in "Lessons learned from Non-Marriage experiments."

Daniel Schneider, a sociology professor at the University of California at Berkeley, found that career academies were the only jobs-training program that also helped boost marriage for men. He concluded that when a program is successful at giving men financial footing at career academies, it may also give them the confidence to take the next step and care for a family.

Todd Agne, right, hugs Marvin Roseberry after the graduation ceremony for his “Dad’s Making a Difference” class.

In November, the 15 men who made it to the end of Agne’s 13-week course were invited to a dinner and graduation ceremony. At that point, 168 men had graduated from the class and, of that number, 135 had found work since 2011.

Men were excited to introduce Agne to the children and women they had talked so much about. Others weren’t ready to let go. They pulled Agne aside and pressed him for last-minute advice.

One handed him a sheet of paper. He had been accepted into Chattanooga State’s welding program.

Agne pounded his fist on the table in excitement and clasped the man on the back.

Then Agne’s phone rang.

“You ready?” he asked the man on the other line.

It was Robert Burson, a former graduate who once had no job opportunities and had no contact with his daughter. Now, he explained, he had earned his commercial driver’s license and just been awarded shared custody of his daughter.

“Todd is good about keeping you level-headed,” he said through the cellphone speaker, pulled over on the side of an interstate in Florida.

Agne interrupted.

“No. It was you,” he said, before explaining that Burson’s tenacity had been the real change agent.

After he hung up the phone, Agne called out the first graduate’s name to receive his certificate.

He wanted them each to leave knowing their value.

“It’s a rare quality to find someone to listen. Please don’t lose that gift,” he said to the first man.

“I would stand by you and go anywhere with you in the right direction,” he told the next.

He then pointed to a man named Marvin, sitting in the back of the room studying for a test he had to take later in the evening at a Bible college he attended.

“I would like my kids to spend a week with you,” Agne said, looking him straight in the eyes once he raised his head. “I would tell them, ‘This is what a man does.”

“Come up here my friend.”

And when the festivities were over, he left them with a simple gift — something that symbolized what he had come to believe about their potential — a brand-new wallet.

en like Tim Jones, a single, divorced father of two boys, needed to be reminded he mattered to his sons.

en like Tim Jones, a single, divorced father of two boys, needed to be reminded he mattered to his sons.

When Jones enrolled in Agne’s class three years ago, he was behind in child-support payments by more than $12,000. The amount had piled up after he didn’t file the right paperwork in court when his seasonal job at an iron foundry had expired, and they kept charging him as if he was making the same earnings. In the judicial system, Jones said, he was treated as if he meant nothing more than a monthly check to his children.

Agne saw that Jones was a hard worker who was desperate to improve the lives of his sons, and when Jones finished Agne’s class he was able to apply what he learned.

During the time of the class, Jones worked at First Things First part-time, recruiting people to take the nonprofit’s parenting and training classes. But he quit the job and moved back in with his mother at 29 when he was caught smoking marijuana and lost the public-housing unit he had planned to use to launch into middle-class life. It was an embarrassing setback since he had been so determined to move forward. Jones had turned to marijuana from time to time over the years in moments of stress or anxiety when he just wanted an escape.

Like so many men in similar circumstances, he often felt very alone. His own father had died of an illness when he was a teenager, and the hurt never went away.

Isolated in Hixson with no car, no income and no access to the bus service, some would have languished, but after nearly a year he mustered the courage to step out again for the sake of his sons.

Tim Jones waits for the elevator with Tariq, center, and Timothy as he sends them off to school in November 2015. Jones will leave Timothy, who is in elementary school, to wait for the school bus outside their apartment while he and Tariq walk on to a public bus stop. Jones has no car, so he takes Tariq to preschool on a CARTA bus.

He wanted his own place when they came to stay with him for half of the week, so he leveraged his connections like Agne had taught him. He found a former classmate who had become a lawyer to help him lower his child-support payments to match his current salary. Then he went back to an old job parking cars at the DoubleTree Hotel. He found a one-bedroom economy apartment across from the YMCA where he could walk to work and to the bus stop to pick up his boys.

Jones knew how important it was to invest in his sons, and he developed a routine when they came to stay.

After his eight-hour day parking cars, after splitting tips with the college students who worked alongside him, he made the journey home again, at one point walking half a mile through discarded fast-food wrappers and broken glass to pick up his boys at Tariq’s day care in Brainerd.

On the way back, he bought chicken and mushrooms with his cash tips and stuffed the food into his backpack, avoiding the easier drive-through, dollar-menu options.

Dinner would wait, though.

Despite the hours of travel and the hours of work, Jones had to follow through with the routine he and his boys had established. So he put on gym clothes for an hour of basketball and sweat before chicken and homework.

Then in January, he was offered a parking supervisor position in Jacksonville, Florida, a chance to launch his career further and make more money. The move would have been a no-brainer had he been a single man. But he wrestled with the idea of leaving his sons.

He made a last effort to stay when he interviewed at the Edney Building, the downtown hub of the city's new innovation district. He told them he could use his experience working with people to help set up and make their events run smoothly.

The decision paid off. He got the job. It was part-time, but if he worked hard it would lead to something more, he told himself.

He wouldn’t be the guy people slung their keys to. He wouldn’t be the man at court they assumed was a bad father. He wouldn’t be the interviewee with a criminal record and no track record.

He would finally be the man he had always wanted to be.

A man, more importantly, that his sons wanted to be as well.