His Chinese food

awaited. Yet the black

thought intruded.

And there was the gun.

Means Matter

There was no plan, no note.

That Thursday morning in August, Ryan Harris just wanted to claw his way to a new mindset.

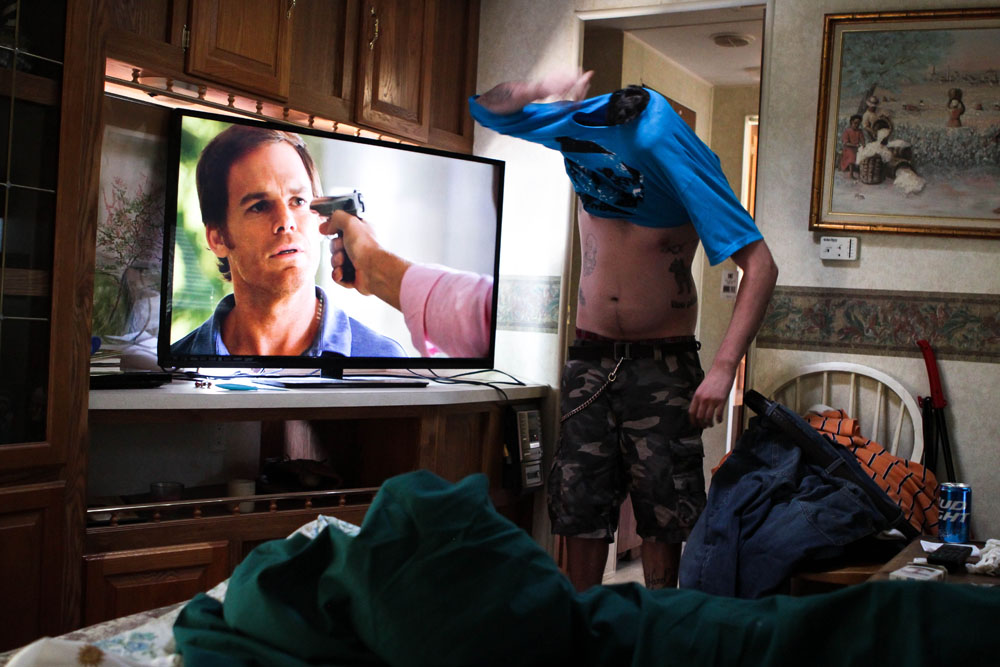

So he took drags on a crack pipe and breathed in clouds of methamphetamine.

Hours later, when the sun set and the uppers wore thin in his system, he downed 12 shots of whiskey back to back and took pills to lay his mood flat — eight Xanax and five oxycodone.

The drugs racing in his body made him feel unsteady, silly, loose and anxious at the same time. So his brain, overstimulated and flooded with dopamine, couldn't regulate the singular penetrating thought, the thought that told him to kill himself.

He couldn't feel any hope when he started to think about his mother, about how she refused to let him see his young son, about the dead friends whose names were tattooed on his back, about his lost childhood spent in and out of wilderness camps and juvenile detention, about the girlfriend he couldn't face losing.

When he told himself that everyone would be better off without him, there was no regulating thought that told him he was wrong.

The only answer was the gun on the table, the gun that his mother had left when she went on vacation.

So he lifted it to his temple, leaving the Chinese food he had bought for dinner untouched.

He spun the chamber and pulled the trigger.

He spun the chamber and pulled the trigger.

He spun the chamber and pulled the trigger.

There is a part of us that is resigned to suicide.

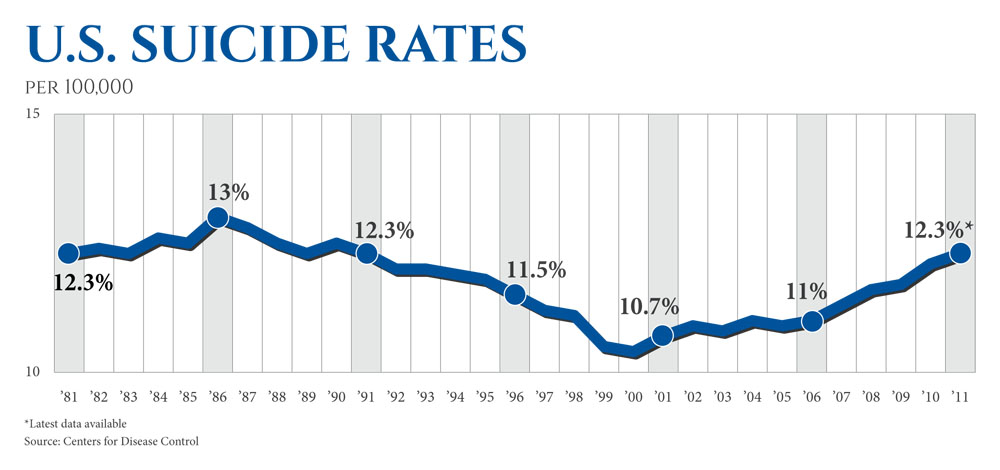

After all, the rates in the U.S. — around 2 percent of all deaths per year — haven't really changed since the 1940s. Strides in science and medicine, the modernization of mental health care away from asylums and lobotomies, the arrival of antidepressants and mood stabilizers, the creation of suicide hotlines, the social push to destigmatize mental illness, nothing has changed the fact that some are determined to self-destruct.

Conventional wisdom says the mental health care system is the savior of the suicidal. If a person is reached in time, psychiatrists and counselors will intervene and make the mind right again, dull the thoughts, the pain and hopelessness.

Prevention groups tell us to look for warning signs, changes in behavior, lethargy, talk about dying, closing accounts, paying off debts, giving things away.

Still, sometimes there are no signs, experts say.

The choice isn't always a slow burn that can be intercepted, and many suicides are neither strategic nor thought out. The leap into death is commonly born of acute emotions, a culmination of agonies pressing down in a single deadly moment, spontaneous combustion.

The time between thought and act is often less than a single hour, research published in the Journal of Clinical Psychology shows. In a Houston study, almost all 153 survivors of nearly lethal suicide attempts said the deliberation took less than a day.

Ryan Harris wasn't obsessed with the idea of suicide. He wasn't determined to kill himself for weeks. He hadn't tried to sell his belongings. He hadn't told anyone goodbye. He had planned to eat his dinner and spend the rest of his night with his girlfriend in his arms.

It was an idea that became real just minutes before he pulled the trigger, an idea made possible by the presence of a loaded gun.

And while the distinction between suicides of passion and those that are premeditated has always been known, the crisis- driven suicidal, those like Harris, are often seen as unsavable, strange aberrations.

But leading experts now say there is a cure we have grossly ignored.

The greatest suicide prevention accomplishment in modern times happened by accident.

It isn't known by many, but those who do know about it call it the British coal-gas story.

For generations, the British heated their homes and stoves with coal gas. The method was cheap, but it could also be deadly because, unburned, it released high levels of carbon dioxide or carbon monoxide. Opening a valve in a closed space could kill a person in minutes.

So asphyxiation by sticking one's head in the oven was a common method of suicide in Britain. It was painless, quick and certain death. In the late 1950s, oven suicides totaled 2,500 a year, half the nation's total suicides.

But a change in the country's energy policy had an unintended effect on Britain's suicide rate. By the time coal gas was replaced with natural gas in homes — a full transition by the 1970s — suicides in the country had fallen by a third.

A similar story played out in Sri Lanka.

In developing countries, many people drink pesticides to commit suicide because they are so easily accessible. One drink can paralyze breathing and muscles within two hours, and worldwide as many as 3 million are hospitalized with pesticide poisoning every year, according to the World Health Organization. In 1985, data from Sri Lanka showed pesticide poisoning killed 220,000 each year in the developing world. Between 1950 and 1995, suicide rates in Sri Lanka increased eightfold to a peak of 47 per 100,000 in 1995.

But when Sri Lanka outlawed the import and sales of WHO Class I toxicity pesticides in 1995 and endosulfan in 1998, suicides in the country fell significantly. By 2005, the suicide rate had been cut in half, according to research published in the International Journal of Epidemiology.

The cases of Britain and Sri Lanka are favorite stories of David Hemenway, professor of health policy and director of the Harvard Injury Control Research Center.

For years, Hemenway and his staff have been studying the relationship between lethal means and suicide and trying to evangelize the message that suicide tools matter as much in the fight against suicide as combating mental illness does.

And in the U.S., the tools he is most worried about are guns.

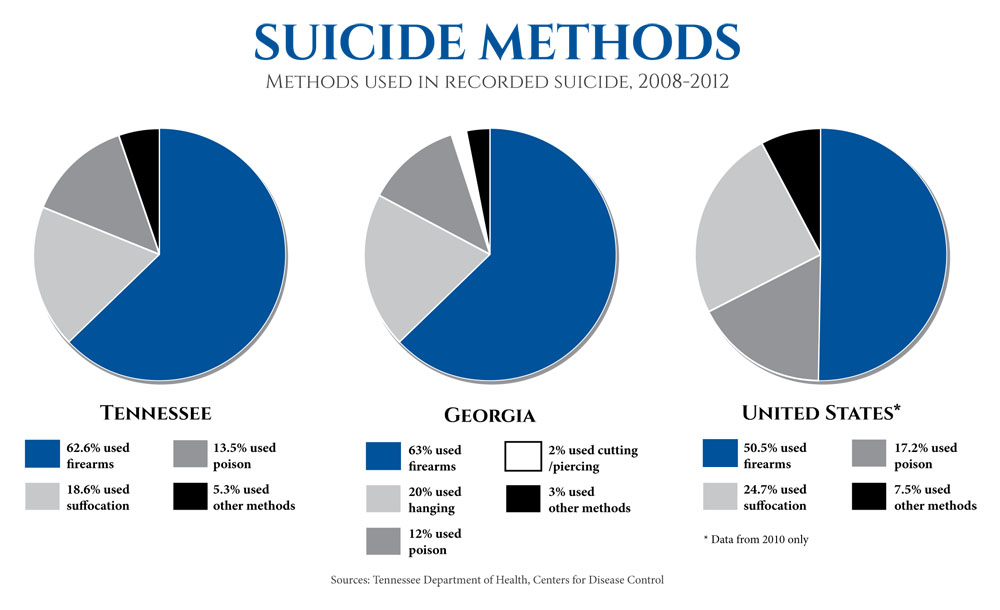

Guns are used in only 2 percent of all suicide attempts, Hemenway said, but they account for more than half of all the fatalities. The most common method for suicide is to take pills or slit wrists, but those methods leave time for people to be saved or change their minds. A gunshot to the head is often final.

In Tennessee, where 43.9 percent of households have guns, according to a study by the University of California at Riverside, there is an average of 900 suicides a year, and 62 percent of those were completed with a firearm. And guns have contributed to increases in the suicide rate over the last few years, especially among middle-aged men.

Hemenway can point to study after study showing that where guns are more prevalent, so are suicides.

Suicide has always differed by region, Hemenway said, but the numbers differ not because certain states have more troubled people but because certain states have more guns.

Hemenway conducted a study in 2007 that compared the suicides in the 15 states with the highest rate of gun ownership — which included Tennessee and Alabama — with the six states with the lowest gun ownership. What they found was that the nonfirearm methods in the two populations were almost equal. Firearm suicides, however, were more than three times greater in the "high gun" states.

And the annual suicide rate in gun-prevalent states was nearly double that in the states with fewer guns.

"The data is so compelling. If there is one thing we know about guns in the United States, it increases the likelihood that someone in that home will die of a suicide," he said.

What Hemenway and other "Means Matter" advocates want is not gun control but a change in the way we deal with guns. Gun owners are not more suicidal than the general population, but their weapons create risk.

Most firearm suicides occur in the home with the family gun.

If parents know their teen is on antidepressants and facing bullying at school, Hemenway said, the guns should be either locked away or taken out of the home. If a friend is spiraling from a divorce or job loss, someone should kindly offer to keep the guns until life returns to normal.

"Friends don't let friends drive drunk. It's the same idea. Let me just hold your gun for a few months," he said.

Doctors should be giving this advice when they know someone is in crisis. Research shows that 66 percent of people who commit suicide have contact with a primary-care physician within a month before killing themselves. But doctors aren't really probing about suicide, Hemenway said.

Gun shops should be giving this advice. Gun training course instructors should be talking about suicide and the risk associated with gun ownership. Many people buy guns for safety, but what they don't realize is that suicides outnumber murder 2-to-1 in the U.S.

When a person comes in to buy a gun and says he doesn't care what gun he gets and wants only a few bullets, that should raise questions, Hemenway said.

"Don't sell that gun," he said.

But right now, he said, that isn't the way we think. Many believe that limiting access to one lethal means will just lead a person to another.

A Harvard survey of 2,700 people asked how many of the more than 1,000 people who had jumped from the Golden Gate Bridge would have gone on to commit suicide some other way if an effective suicide barrier had been installed. Over a third of respondents estimated that none of the suicides could have been prevented.

A similar survey of physicians and nurses in emergency rooms showed a similar belief in the inevitability of suicide. Two-thirds of surveyed nurses thought that firearms suicide deaths could not have been prevented even if the gun had been removed.

But that thinking is simply wrong, and people are dying because of it, Hemenway insists.

Research into bridge jumpers proves this.

The neoclassical Duke Ellington Bridge in Washington, D.C. rises 125 feet over Rock Creek Park, and more than 30 years ago was known as the district's suicide bridge.

Between 1979 and 1985, 37 suicides occurred from D.C. bridge jumps, and 21 of those happened on the Duke Ellington Bridge, according the D.C. Medical Examiner's Office. An average of four people leapt to their death from the bridge each year. The Taft Bridge, which had an equally treacherous drop but a higher barrier wall, ran perpendicular to Duke Ellington, and had fewer than two suicides on average a year.

When three people leapt from Ellington in a 10-day period, many began to call for suicide barriers, but the National Trust for Historic Preservation fought the move in court.

They argued, like many have, that a barrier would mar the appearance of the historic bridge and that the suicidal would simply go elsewhere. They could easily jump from the Taft, for example.

The barriers went up anyway, and five years later a study was conducted. Suicides on Ellington were eliminated completely, but they also barely changed at the Taft.

Another study done years earlier of attempted suicides at the Golden Gate Bridge shows the same results.

For years, the Golden Gate Bridge, one the world's greatest suicide magnets where more than 2,000 have met their end, has been at the center of the debate over suicide means.

Last year, more people jumped from the Golden Gate Bridge than ever before. But a suicide barrier has never been erected because of the same argument made in the case of the Duke Ellington Bridge. The suicidal will find another way.

Still, academics say that argument should have been put to rest in the 1970s when Richard H. Seiden, a professor at the University of California at Berkeley, published his report, "Where Are They Now?," which looked at how 515 thwarted suicide attempters between 1937 and 1971 ended up dying later in life.

According to their death certificates, only 6 percent of would-be jumpers went on to kill themselves. Suicides that might have been mislabeled accidents would increase that percentage to just 10 percent.

So 90 percent of suicide attempters got past their desire to end it all. Since Seiden completed his work, almost 90 more similar studies have backed up his findings.

"The major hypothesis under test, that Golden Gate Bridge attempters will surely and inexorably ‘just go someplace else,' is clearly unsupported by the data. Instead, the findings confirm previous observations that suicidal behavior is crisis-oriented and acute in nature," Seiden wrote in his summary years ago.

In a crisis, the mental anguish is so severe that many are just looking for a simple and quick way out.

Delaying the availability of this "out" gives time for the mind to clear and for some hope to creep back. Just the thought of having to go through the set-up of another form of suicide might derail a person's efforts, Hemenway said.

In a gun-fervent Southern state where gun shows are advertised on billboards, handguns are hidden in cars and guns fly off store shelves at a mention of tougher gun laws nationally, it's hard to talk about the link between guns and suicide.

Suicide in and of itself is a hard conversation, one often avoided because of the stigma it still carries in places like Chattanooga. The idea of gun control is just as touchy.

At Shooters Depot, one of the largest gun stores and shooting ranges in Chattanooga, a worker who didn't want to give his name said he would never want to talk about suicide at the store.

He remembers learning about it in school and called it a "weird deal all the way around."

Suicide in Tennessee is one of the leading causes of death — even more common than death by car accident — but the man at the gun store said suicide was rare and that suicide by gun was more rare. Talking to a customer about the risks seemed unnecessary, he said.

"It's not necessarily our side of things to talk about," he said. "It would be an awkward conversation for anybody."

Just last year, officials with the Tennessee Suicide Prevention Network decided to make gun safety a part of their prevention efforts, modeling what they would do after a program in New Hampshire.

In New Hampshire, a review of medical examiners' records showed that once a month a suicide was completed with a recently purchased firearm, revealing that gun shops could be a hub for intervention. So firearm dealers in the state were encouraged to display prevention material and gun shop workers were trained on how to spot people who might be looking for a gun to end their life.

Scott Ridgway, executive director of the Tennessee Suicide Prevention Network, told USA Today in April 2013 that his workers would distribute similar materials to the more than 1,000 gun stores in Tennessee by that September. More than a year later, they are yet to be displayed in Southeast Tennessee.

The material warns firearms retailers that 63 percent of suicides in Tennessee over the last five years involved guns and urge that their vigilance could save a life.

They are told to look for small signs: emotional countenance, avoiding eye contact, disinterest in gun maintenance, mentions of a recent crisis.

Ryan hid from the spring sun under the canopy of a camper trailer where his father lives. Sitting at a picnic table, he played with the winged seeds of a maple tree. He flung them out before him and watched them swirl to the ground, enraptured by the samaras' flight.

He doesn't remember lying in a pool of his own blood. He doesn't remember the doctors sewing his head shut. He doesn't remember the days of coma, his family by his bedside waiting for him to wake up. In his mind, there is just the dark moment, the .22-caliber pistol pointed at his head.

Then he was awake. Alive.

The doctors said he wouldn't walk, that he would be completely paralyzed on his left side, but his legs began to move. He still can't grab a door handle with his left hand. He still can't pull his pants up without help or hold his son in his arms or taste food or smell. He drools when he talks sometimes.

Sometimes he falls to the ground and seizes up and bites his tongue, scaring his father. The brain damage from the attempted suicide is severe.

Some people may say that he is still bound for suicide, that the darkness that crept to the forefront is just lingering in the background, one crisis away, but Ryan says he doesn't want to die anymore. He says he never really wanted to die. It's just that dying seemed so easy in that moment with that gun on the table.

In the months following his suicide attempt, he changed. He quit doing hard drugs and started going back to the church he attended as a teenager. He says he is washed by the blood of Jesus and this new start was given to him for a reason, for good.

On a recent night, he went to a meeting for other victims of traumatic brain injury and a man was there who had attempted to shoot himself like Ryan had. The man shattered his frontal lobe, but like Ryan he survived. He lives with his mother now and hopes to work again one day, but his emotional life has flatlined.

At a table playing a board game, Ryan tried to tell him how happy he was to live, how life had so much meaning now.

The man shook his head.

"The grass is greener," Ryan said. "Things you always took for granted, you don't no more. You respect that you have life."

Life isn't perfect. Ryan will probably never be able to work. He and his mother are still fighting. His girlfriend's parents don't like him, and he is living in his dad's small camper. The disability check of $720 a month is the most he may ever earn.

But he sees potential.

His girlfriend just found out she is pregnant. He keeps the small plastic positive test in his wallet.

He wants to buy her a ring.

"I feel like I get another chance."

Credits

By Joan Garrett McClane

Photography by Maura Friedman

Design, graphics and production by

Michael Ku, Laura McNutt, Maura Friedman, Ken Barrett

Research was contributed by Mary Helen Miller