All White. All middle aged. All men.

SUICIDE'S NEW TARGET

Take care of the outstanding bills.

If you don't love me, no one can love me and I have to die.

I want to be in peace. I want to be with momma.

Then the slip of a noose or the pull of the trigger. Then the sirens. Then the bodies packed away and buried. Then the whispers and the questions and the bitter tears.

All white. All middle-aged. All men. And now all part of a baffling suicidal subgroup.

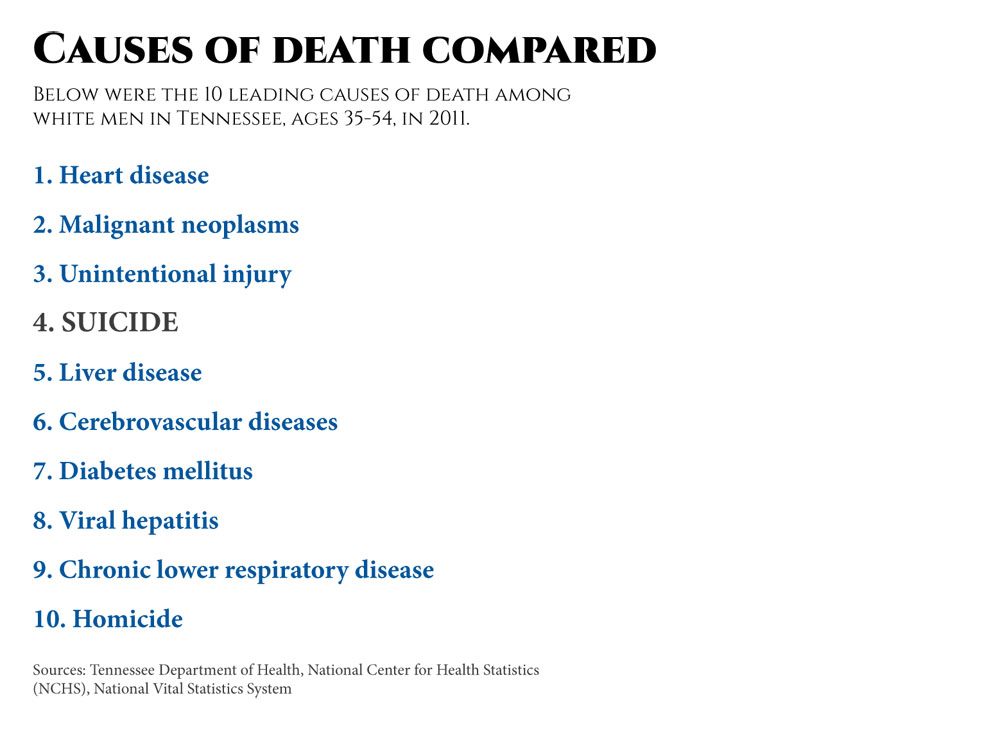

Suicide has always plagued the terminally ill and the troubled adolescent. It has always lurked among the schizophrenic and bipolar, but more than ever suicide is taking men at midlife, working men with children and years to live. Middle-aged white men are killing themselves at alarming rates. Suicide is now the fourth-leading cause of death for men under the age of 65 across the U.S. In Tennessee, it is the fourth-leading cause of death — following heart disease, malignant neoplasm and unintentional injury — for men between 35 and 54.

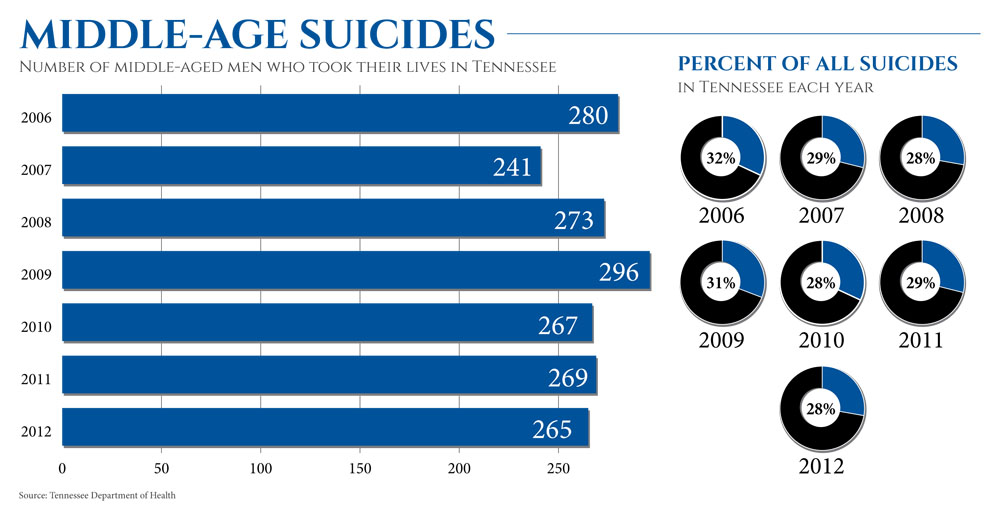

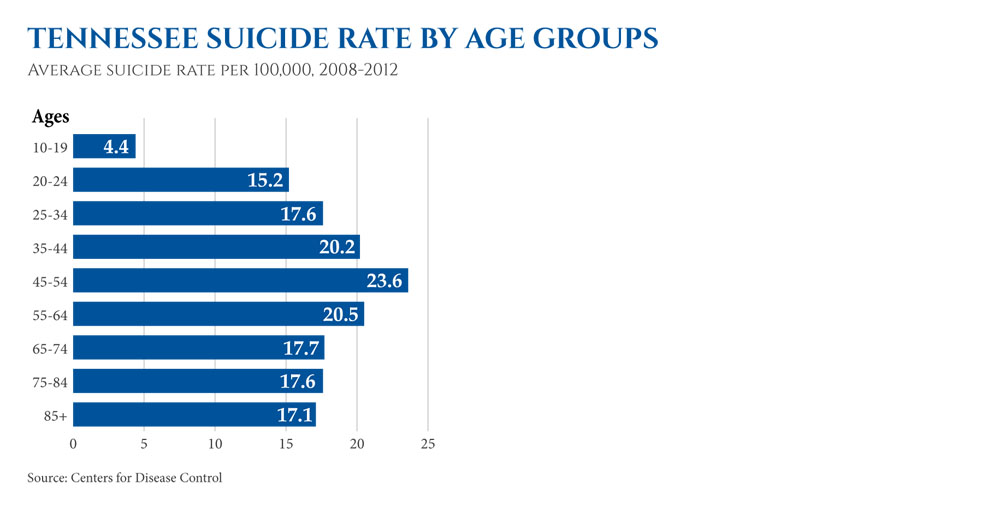

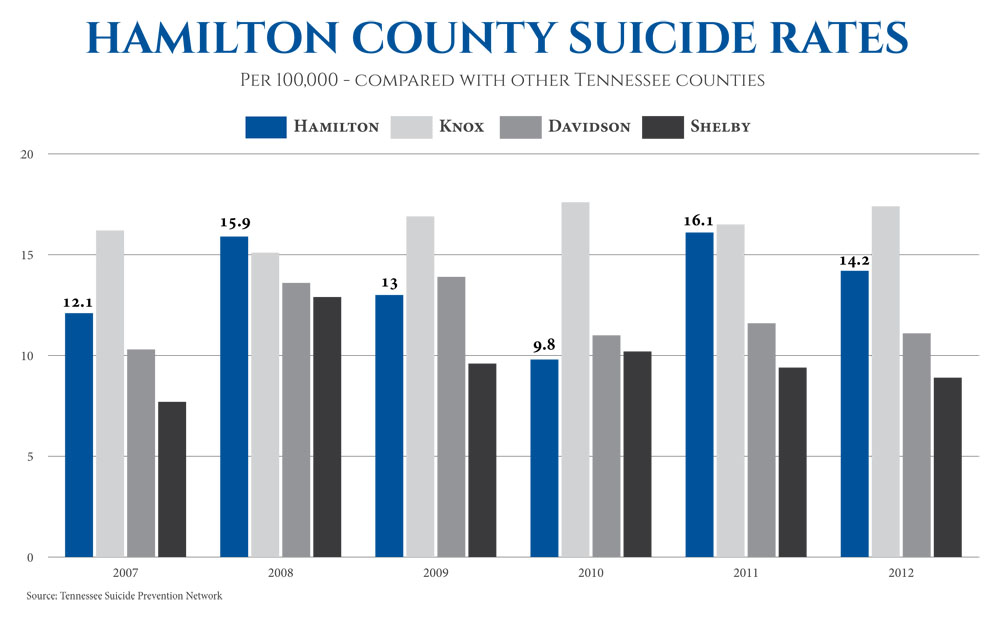

The suicide rate for the middle-aged is more than four times the teen rate in Tennessee, and the number of middle-aged men committing suicide has been rising especially since the Great Recession set in, experts say.

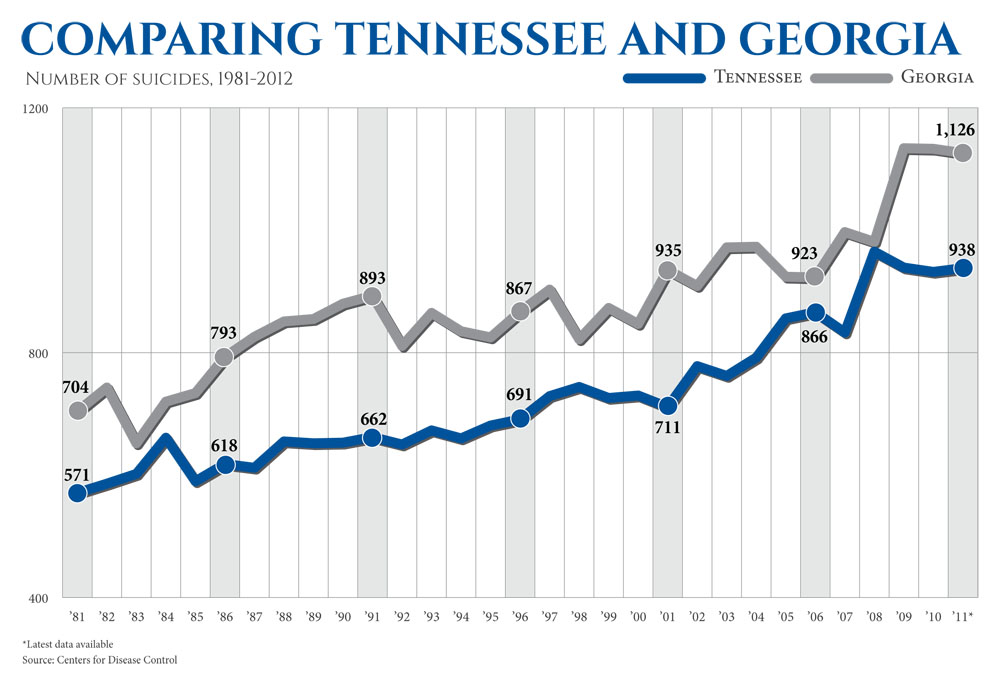

Across the country, the number of adults ages 45-64 who died by suicide rose by a rate of 17 percent between 2006 and 2010. Overall, the national suicide rate among people of all ages increased by about 11 percent during that same time period.

There are many contributing factors to this uptick in suicides. Middle-aged men lost jobs at alarming rates during the recession. Then when the economy rebounded, many of their jobs — or jobs that would pay comparably — never came back. Fewer men are married or connected to traditional social pillars. Pew Research shows the percentage of married adults has dropped from 72 percent in 1960 to under 50 percent.

And fewer are educated. Since 1982, women have earned in excess of 10 million more college degrees than men, according to data from the U.S. Department of Education.

Then some find themselves with enormous pressure, caring for both their children and their aging parents. They see their health declining, their youthful good looks fade.

Many find themselves disillusioned in the prime of their lives, said Tim Tatum, outreach coordinator for the Suicide Prevention Network in southeast Tennessee.

On top of all that, these baby boomers have access to prescription drugs and guns and they won't seek help.

Many of these men of a more tight-lipped generation still think their manhood would be marred by a counseling appointment or depression medication. They call it psychobabble or hogwash.

And suicide prevention workers find them nearly impossible to reach, said Scott Ridgway, executive director of the Tennessee Suicide Prevention Network.

Teenagers can be targeted in their schools. The elderly can be targeted in nursing homes. Veterans can be found at the VA. But mentally unstable men can easily never have had contact with prevention workers.

"The families say they didn't see the warning signs," Ridgway said. "They didn't see this was happening. ...It's harder for men to talk about the struggles they are going through."

Tracie Nave talks to counselors about the day her father, Clinton Penny, took his life. They hadn't always been close, but they were in the last months before he put a gun to his head, before he called 911 and told them to send an ambulance for his dead body, before the emergency responders found the "do not resuscitate" note on the table.

He was 69, and he always came to her son's baseball games. He volunteered at the YMCA and went to church on Sunday and had a wife. That was the face of her shy father, she tells her counselor. But he was still water with secrets beneath.

After he was gone, she found Alcoholic Anonymous books in his belongings. She found prayers written, begging for the demons to let up. She found medications for Parkinson's disease, which would have progressively slowed and stiffened his movement. She learned that he and his wife were divorcing. The decision was final the day before his death.

But he never asked for help. He never cried where she could see.

"Everything was so secretive," Nave said.

That was seven years ago.

"It just shattered my life," she said, crying.

Amanda Stokes can tell virtually the same story. She didn't know how sad her husband was. She didn't know how hurt he was by their arguing, how upset he was about being laid off from the trailer company where he had worked as a supervisor. She promised him he'd find work. Even though their marriage was rocky, even though he drank too much, she told him she loved him. They had a son they adored and had known each other since she was 13. He had attempted suicide before by drinking household cleaners from under the sink, she said, but she never believed he would really go through with it.

Then one morning in January she found him hanging. He was just 30.

A note nearby:

"If you don't love me, no one can love me and I have to die."

"I cut him loose from a noose hanging from my stairwell. The next thing I knew, they were carrying him out in the body bag," she said.

She felt like a fool.

"I told him there was nothing wrong with him," she said. "He was fine."

Credits

By Joan Garrett McClane

Photography by Maura Friedman

Design, graphics and production by

Michael Ku, Laura McNutt, Maura Friedman, Ken Barrett

Research was contributed by Mary Helen Miller