He was sweet. Loved.

But he hid himself.

And became one of those lost

Every 16 minutes.

Into The Darkness

They meet in a circle, under the small framed picture of a smiling Jesus, Kleenex on hand. Pam Williams and Gloria Hastings try to make the meetings at the small church off Brainerd Road when they can. Once a month for nine years,

ever since Bubba did

what he did

on Aug. 18, 2005.

This group that talks and wails is a shifting family of sorrows.

There are people who call for directions and never show. People who come once, sob, and never come again. The three- or four-timers. The shells in shock. The confused, who rummage through left-behind belongings for answers.

There are the guilty who wonder if they loved enough, if they could have stopped what happened.

And there are the indignant, who call the dead "bastards" for leaving them alone with the mess.

Here, on the third Monday of every month, Pam and Gloria hear stories of children finding fathers with parts of their heads missing. They've heard from wives who have cut down limp husbands from hanging ropes. They talk to people who spent hours cleaning up the blood without help.

Still, even after all these years of listening to the freshly wounded and repacking and unpacking their own grief, the sisters can't put these deaths, these suicides, in a neat box.

Sometimes the act is planned, expertly executed. Sometimes it's haphazard, driven by a collision of forces, passion. Sometimes there are cries for help, sometimes not a word.

"You don't understand. You don't comprehend," says Tonia Shadwick, the group's facilitator, between tears.

"My dad was brilliant. ... He had a good job. He could draw things. He could paint things. He could mold things. He could do anything."

Experts say the recession broke our spirit, that middle-aged men are especially glum in a society where high-paying jobs are harder to come by and retirement savings are sliced. They say childhood cruelty is a schoolyard epidemic driving children and teens to end their lives before they even start. That the strain of more than a decade of war in Iraq and Afghanistan has turned soldiers on themselves. They say people are still afraid to see counselors and get pills, that too many are afraid to admit their hearts hurt or that they see no point in going on.

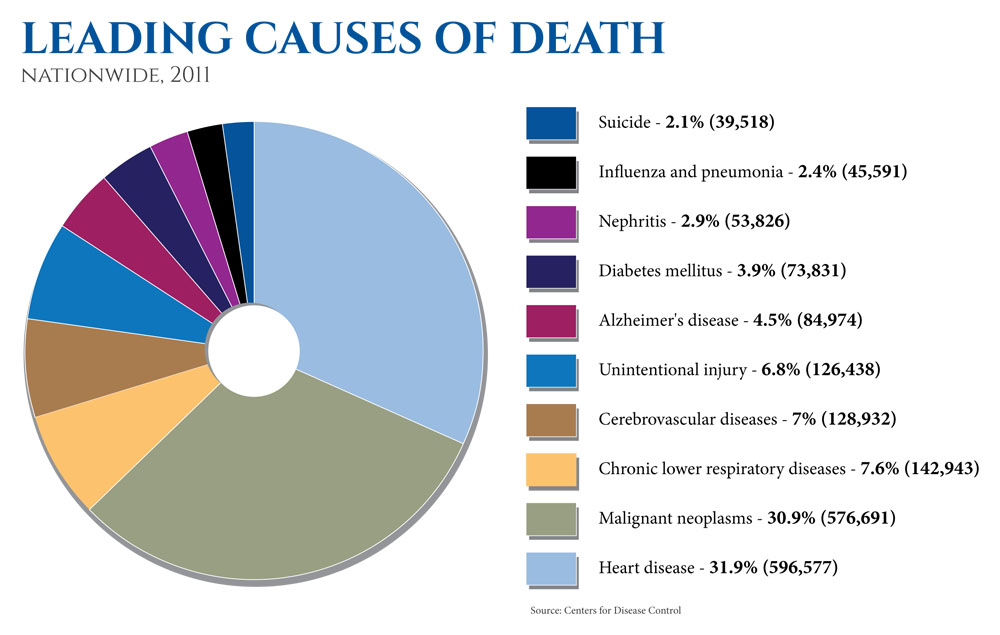

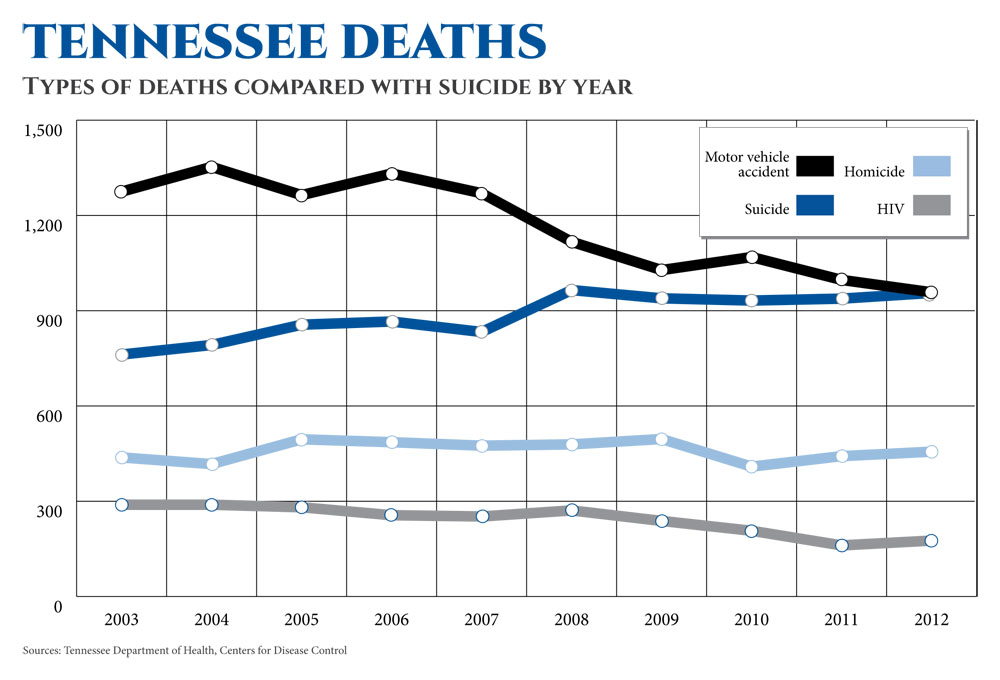

Still, it's hard to pin down why a suicide happens every 16 minutes in this country. It's hard to understand why more people die of suicide than from car accidents or violence; hard to figure out how to stop them or how those left behind live with them afterward.

Although 90 percent of the people who complete their suicides show signs of mental illness, it's never just the faulty wiring of the brain. It's never just the divorce or job loss. It's never just one missed sign.

So suicides are a riddle and a paradox.

We deny death. We take vitamins and go for annual checkups and buy juicers and exercise. We glorify advanced medical technology and run 5Ks to battle cancer. We are a world obsessed with longevity.

And we despise this act that flies in the face of life. We close our ears to the suggestion that life can lose its worth and that death is gain. We are angered by the selfishness that leaves behind scarred children, parents and widows.

But we feel pity, too.

In 2012 nearly 1,000 people committed suicide in Tennessee — a 34 percent increase from 16 years earlier — leaving thousands more friends and family deeply affected.

Experts call the family left behind the "survivors," but they don't always survive.

Trauma plagues them most of their lives. They have anger but nowhere to send it. The killer was the victim. The victim was the killer.

They face well-kept secrets, hidden addictions or crimes or illnesses unearthed after death. So suicide compounds pain. There is the loss of life and the loss of truth, a realization that while you knew someone, you didn't know him at all. In some cases, their own thoughts of suicide can win out in the end. Their thinking can become poisoned, experts say, since suicide is now in their frame of reference. A new out.

Like so many men who took their last breaths with a gun in their mouths, Pam and Gloria's brother hid himself and left a million questions when he was gone.

Wasn't he a good man, a funny man? Wasn't their family a loving family? Wasn't his life worth more than the measure he gave it that day in August?

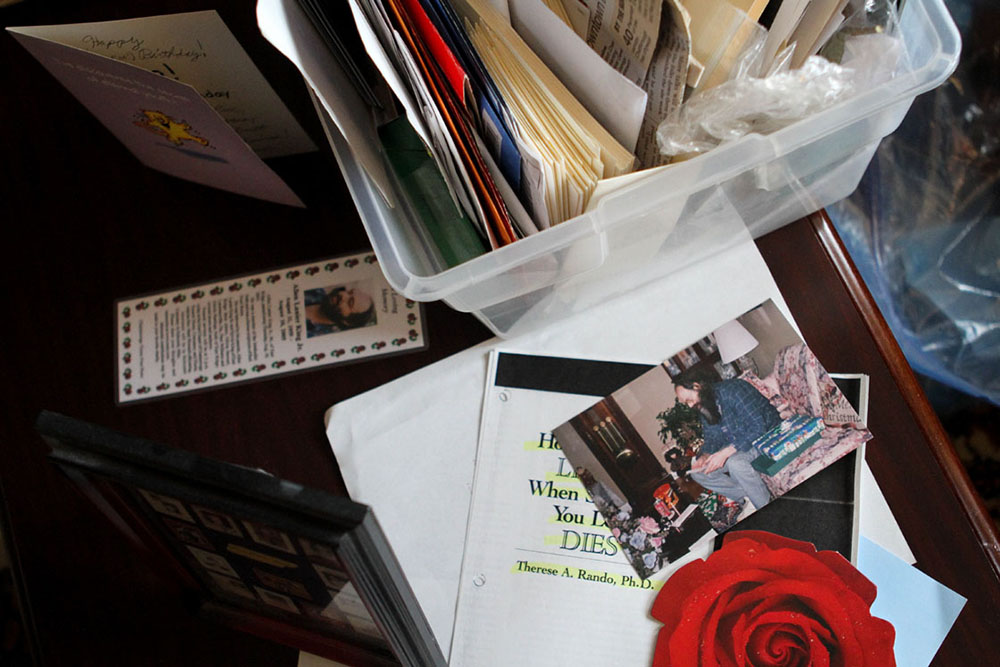

Now his face is on a square of a suicide memorial quilt in Nashville. Now he is a framed picture, boxes packed away. Now he comes to them, they believe, as hummingbirds, flittering so close and so fast, so small in this world.

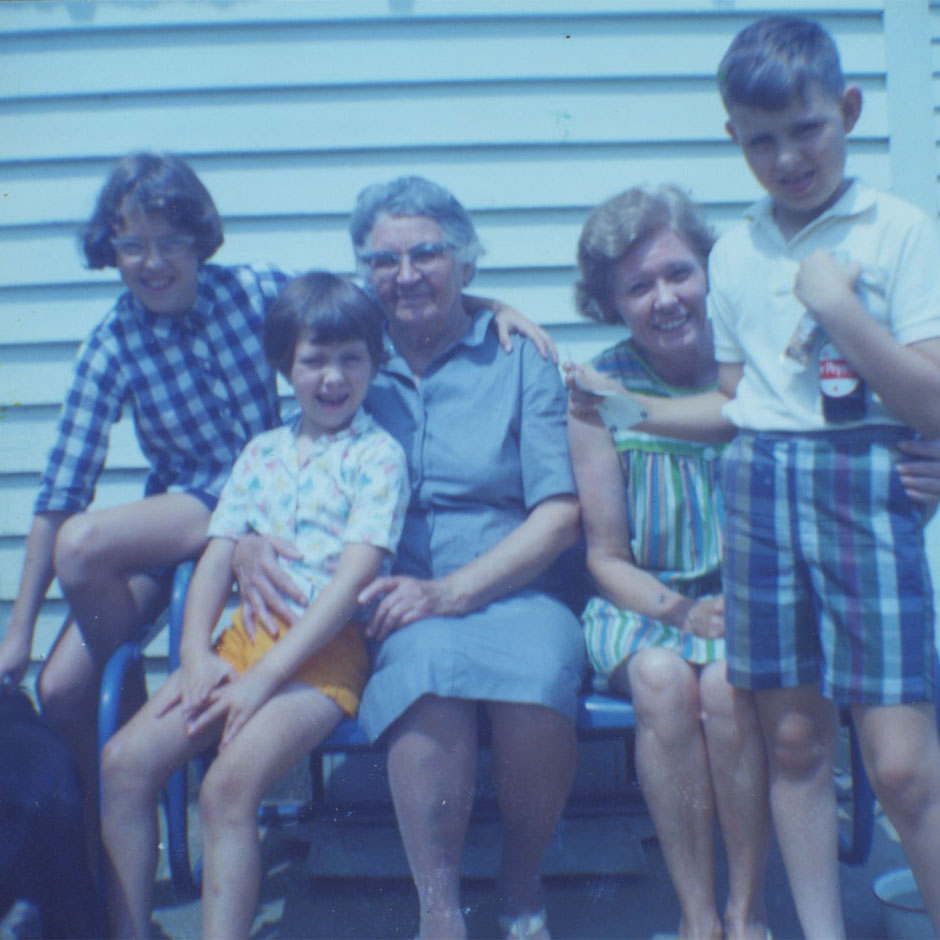

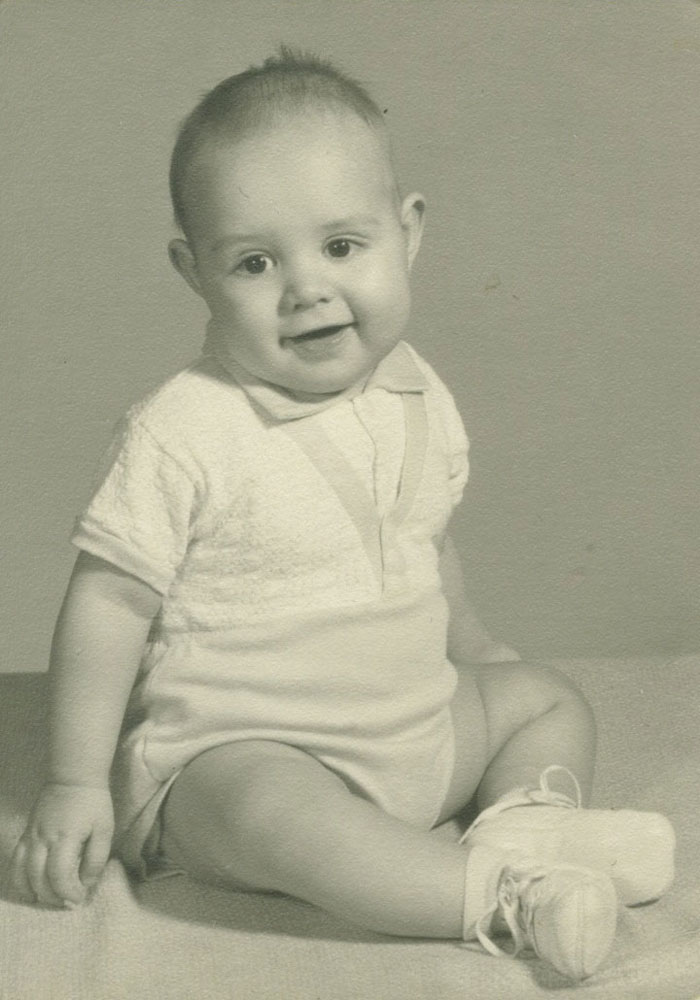

His name was Allen Lanier King Jr., but his sisters called him Bubba, Bubski.

He was both the comic relief from the high expectations of strict Southern parenting and the cerebral pillar of the family. When someone wanted to know the capital of Poland, they called Bubba. When Gloria had an idea to drive across country or write a book, Bubba offered wisdom.

"He was always practical," she said.

He read Will Durant and Friedrich Nietzsche and actually comprehended their philosophical ponderings. He was a master at the strategies of chess.

But his days were spent working with his hands, not his mind. He wanted to go into the military but couldn't because of an irregular heartbeat. So he stocked produce and lined commercial freezers with microwavable meals and bagged vegetables. While his sisters pursued and finished college, he worked his way from bag boy to assistant manager at the Red Food grocery store in Brainerd.

He was sweet, self-deprecating. "Happy Birthday DeDe," he wrote to Gloria in a scratchy left-handed scrawl when she turned 28. "From your grateful and 'somewhat' magnificent brother."

He was predictable, with the exception of a strange and brief move to Florida in 1984. He came home and never said why. He never worked as a grocery manager again.

And he was sensitive. In 1993, an ice storm made him late for work, and his manager yelled at him.

"You are unreliable," the manager told him. The scolding devastated him so much he never returned to the job.

Instead, he moved into the basement of his elderly parents' home to become their full-time caretaker.

During the week, he would drive his parents back and forth to their doctors' appointments and make sure they took their pills. He cut the grass and watched television with them.

He answered their every call and demand, Pam said.

At the time, the sisters were relieved Bubba had been willing to take the burden on so cheerfully. Both were married and had blooming lives with friends and plans.

Bubba never complained about the responsibility, even though he was young, just in his 30s.

He never said he was depressed or that he was sad or that his life hadn't amounted to all he had hoped. He never said he wanted to die.

Only now, looking back, can his sisters see the hints.

After more than a dozen years of living in his parents' basement, he quit cutting the grass. Even when his father insisted, Bubba would sit with his arms crossed and ignore his father's orders.

He wouldn't shower for months at a time, and his beard grew long.

He stopped reaching out to the people he called his friends. He stopped leaving the house.

Instead, he stayed in the the basement, playing on his computer or reading or watching the Atlanta Braves. When family visited, his jokes turned to gallows humor, they recall.

"I could have been a contender," he would say, mimicking Marlon Brando in "On the Waterfront."

Sometimes Pam would visit and see Bubba sitting in the dark, in silence.

"Maybe you could get out more," she would say.

"There is nothing wrong," he would retort. "Mind your own business."

Then he would appear happy again.

He would go on a trip or start cleaning himself up a little, and the sisters would breathe a sigh of relief.

All the fears, they pushed those aside.

Bubba is fine. Bubba will be fine, they told themselves.

A week before Bubba ended himself, Gloria remembers sitting with her brother watching "The Andy Griffith Show," the haunted house episode. It was a show they had watched over and over again as children, and every joke was memorized.

Barney and Gomer go into the haunted house, and Gomer goes behind a false wall and disappears. And the look on Barney's face made Gloria and Bubba laugh so hard their cheeks hurt, she remembers.

She called him a few days later to tell him about another episode she'd seen, another funny moment she thought he'd want to share, but he never called back.

It was a Wednesday around 1 p.m. when Pam came by to drop off the groceries and help clean their parents' house, the weekly routine.

When she went into the bathroom to wipe the counters and toilet, she could hear Bubba down in the basement through the heating vent, the sound of guttural mumbling without clear words.

Pam looked at her mother.

"He does that all the time," Pam's mother told her.

She was afraid to walk down the basement steps. She was afraid he had gone dark again. When she descended halfway, she spoke to let him know she was coming.

"Hey, Bub, it's me," she said.

"Oh, you're here, good," he answered, not a sign of anger in his voice.

When she got downstairs, she said, he was sitting at his desk, and she sat down beside him.

And then like Gloria, Pam watched him smile for the first time in a long time.

"He was glowing," she said. "There was something serene about him."

The two talked for a while in the basement and drank Dr Pepper. Pam complained about her teenage daughter, and they laughed. She had just moved into a new house, and Bubba promised to come see it in the next few days.

"I remember thinking, ‘Oh, Bub, I'm so glad,'" she said. "He's happy. He's happy."

Bubba gave her a list of groceries to pick up for him, some Advil and cough drops. His birthday had been a few days earlier, and he gave her two birthday checks for $20 apiece to cash for him and bring back the next day.

When she left, Bubba stood at the end of the driveway to direct her out, a routine kindness.

Typically he went back into the house when he saw her drive off, but this time, when she looked in the rear-view mirror, she could see him standing beside the mailbox watching her pull away.

She thought about turning around but didn't.

First there was a boom, then smoke filtered through the vents.

The rest are choppy memories: Pam steadying herself on her car and putting a hand over her mouth; Gloria falling to the floor like spaghetti; their parents sitting stiff on the living room couch with cold hands; the bags being carried up from the basement; their brother-in-law and nephew going into the basement to mop up the blood; Pam thinking the whole scene was a lie, one of Bubba's dark jokes.

She had just seen him that day. He was happy. He needed his groceries, his birthday checks cashed.

Bubba had used their grandfather's sawed-off shotgun. He put it in his mouth after midnight. And his explanation was left in quotes written on envelopes and loose paper around the basement.

He used the words of the Nez Perce Chief Joseph in his surrender to the United States after a three-month battle over Indian lands in 1877.

The most poignant words were written on an envelope sent from the Tennessee driver's license renewal office.

"My heart is sick and sad. I fight no more. Forever."

The periods at the ends of the sentences were scratched in so dark they looked like black holes.

Gloria started a journal the night Bubba died.

She wrote about the firetrucks and the stretcher in front of her parents' house. She wrote that the sights and sounds felt unreal. She wrote about her regret, all the days she didn't call him, all the days she didn't see him.

"The phone rang last night and I didn't pick it up!! What if it was him????"

Guilt chewed at her every day. She constantly wondered if she could have saved him. She constantly thought about the phone call that she missed. She had been a trained social worker but had been oblivious to the signs. Not long before he killed himself, Bubba had said he wanted to sell his computer. Why hadn't she picked up on that?

A month later, after they had buried Bubba at their childhood home in Mississippi, she drove to the store for food and a Bruce Hornsby song on the radio threw her into hysteria.

"That's just the way it is. Some things will never change. That's just the way it is."

She became so undone that she had to pull over and weep. She couldn't stand to see people driving around her. She couldn't stand to see them laughing.

"How can the world go on so cruelly," she thought.

When she finally was able to handle daily tasks again, she felt strange, she said, like people were watching her, like they knew what Bubba had done.

In smaller, Southern places like Chattanooga, medical examiners are still wary of labeling deaths as self-inflicted. Pastors are careful not to mention the act in their funeral eulogies. Family bury the dead and say they died accidentally.

To the Sunday morning faithful, who believe God gives life and God takes it away, the choice is a stain, a weakness, an unforgivable sin.

But she wanted to believe Bubba was in heaven where she could see him one day.

She clung to the words she was told when she called a prayer line the night Bubba died.

"Release Allen into God's hands; release the guilt, the blame, the responsibility, the need to understand. He is at peace."

The first time Gloria and Pam went to a support group meeting, they drove around in circles in the parking lot, trying to talk each other out of parking and going inside.

"Do you want to go?" Gloria asked.

"Do you?" Pam answered.

"I don't know," Gloria said.

Inside the meeting, they had planned to be composed and straight-faced. Gloria didn't want to reveal her brokenness. But listening to the speaker who had lost his young son to suicide made her cry before she ever mentioned Bubba.

The more meetings they attended, the more they revealed about themselves and their pain. They would try to do what Bubba couldn't.

Pam talked about how her relationships between her daughter and her husband had been strained since Bubba's death. Her husband didn't want her to see Bubba's dead body, but she told him she had to.

She told about how her daughter had made her a sign for her birthday and put balloons through the house and how she had attacked them all with scissors like a madwoman.

She talked about how a year after Bubba died, her first grandchild died after living 18 hours, and how this death made her start thinking about killing herself.

She didn't save Bubba. She didn't save that baby. So what use was she, she thought.

Gloria shared her own thoughts of suicide. She had been diagnosed with lupus and lost her ability to work.

"I prayed to die," she said. "I prayed very fervently to die."

In her journal she wrote a note to Bubba telling him there were moments she didn't want to fight anymore, that kidney failure and the chemotherapy for lupus were wearing her too thin.

"I would be reunited with you," she wrote in June 2007.

Then a voice inside her head would tell her to keep going.

"I don't really want to die. I just don't know how to make the pain stop. I wonder if that's how you felt."

Eight years later, they try not to think about the gun and the smoke. They try not to think about that night.

They stay in counseling. They take their medications. They do what they wish Bubba had done.

It's taken years, but when they think of him they don't imagine him as he was before he died. They imagine him in the respites between his loneliness and anger and sadness, when he was not a risk but just their brother.

They remember the breeze that brushed by them, a moment of peace at the burial that they swear Bubba sent to them.

They remember the day when they sat on the porch and a hummingbird flittered and paused for minutes before them. They remember the summers since when they planted flowers for the hummingbirds and hung feeders.

They remember finding and keeping hummingbird figurines, seeing Bubba in the tiny creatures.

Recently, they read a poem Bubba wrote when he was 11 that reminded them he was once a child full of joy.

"I know of a place in the farm country of Mississippi. … Underfoot is acre after acre of rolling green grass, dotted here and there with dandelions, you come to a clearing and before you is a pond, arraying in golden splendor as the sun's light is reflected off its still water … you hear the shrill cries of frogs as they scamper into the safety of the water, you see the hoof prints of cows preserved in mud, the pond seems to hold you in a trance … all is peaceful."