On the second floor of the Chattanooga Public Library, past a locked door and a row of shelves stacked high with aging microfilm, 69-year-old Eleanor Cooper left the last of the boxes, brimming with documents.

Well, all but one.

One remaining box she kept at her home on Missionary Ridge. She planned to read over its contents one last time before releasing the papers, now decades old, to be catalogued in the public record.

Some of the letters contained in carefully ordered manila folders were personal, even painful, and she would have to swallow hard to share them.

Finding, collecting and organizing the letters, emails and notes from the 1980s and 1990s, which many considered trash, had been thankless work. Still, year after year, Cooper kept at it.

Many felt they knew the narrative of the Chattanooga renaissance. Highly polished versions of it had appeared again and again in newspapers, magazines, books and political speeches for decades, and tucked within each was a certainty: Chattanooga held the rights to a formula. Former mayor Bob Corker, now one of the most powerful members of the U.S. Senate, would eventually call it “the Chattanooga Way.”

But only a few people knew the real story behind the city’s rebirth.

Cooper, a retired community organizer and nonprofit organization head, was an insider who knew and worked beside the cast of characters responsible for one of the most celebrated cases of urban revitalization in American history.

And even she sometimes wondered if the renaissance narrative deserved such acclaim. The very question sent her back to college in 2008, where she spent five years researching and writing her own 350-page answer.

Was it a true, populist reinvention of a post-industrial Southern city, or just a public relations campaign strapped to a slick comeback story? Did the original true believers — idealistic baby boomers from some of Chattanooga’s dynastic families — really invent a system for lasting change, or just pave the way for an elaborate rebranding of the city’s tourism industry that ignored its most intractable problems and vulnerable citizens?

Cooper knew the truth. It lived at the library, hidden in those boxes and locked in the hearts of a handful of people, living and dead.

This is the unvarnished, untold story of their dreams and despair. These are the lost chapters of the Chattanooga story.

In the spring of 2016, the city seemed caught between two energies.

On one hand, Chattanooga was a boom town, and the physical proof was everywhere. East M.L. King Boulevard, long neglected, was coming to life as trendy restaurants and high-rise apartment complexes cropped up to cater to the expanding University of Tennessee at Chattanooga. Meanwhile, the empty, gold-windowed, former BlueCross BlueShield headquarters a few blocks west was on its way to becoming a high-end Westin hotel.

The central city was so filled with construction projects that spring that pedestrians were finding it hard to navigate traffic cones and fencing.

For years, local money had fueled downtown’s growth, but outside capital was finally flooding in. In fact, 2016 would prove to be a tipping point. For the first time, half of the projects in the city’s urban core were being funded by out-of-towners.

Highly educated newcomers, fleeing larger and much more expensive cities, were coming to town to fill new jobs and buy condos. To them, there was no buyer’s remorse. Chattanooga was, as Outside magazine claimed, “The Best Town Ever.”

On the other hand, much was brewing beneath the surface.

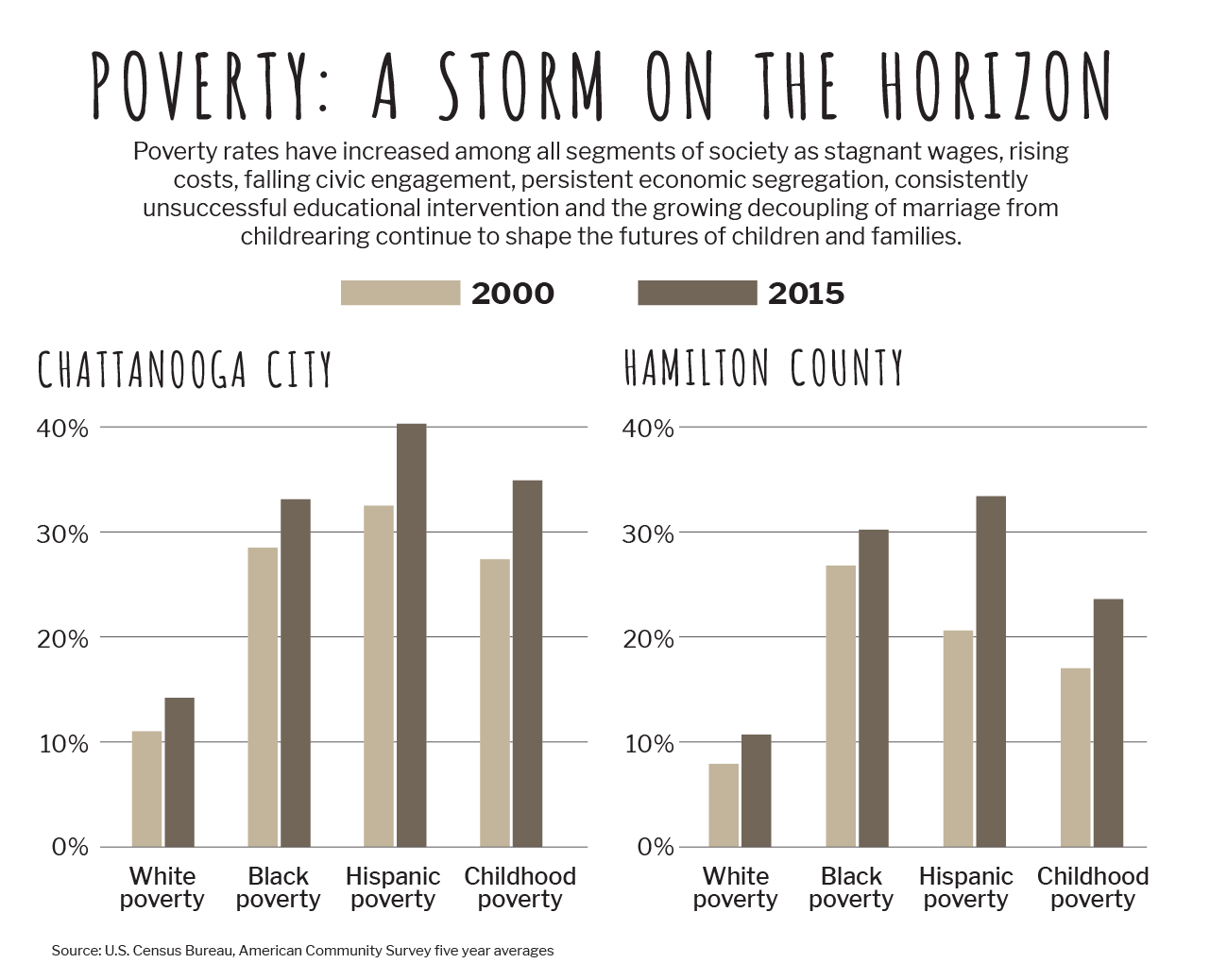

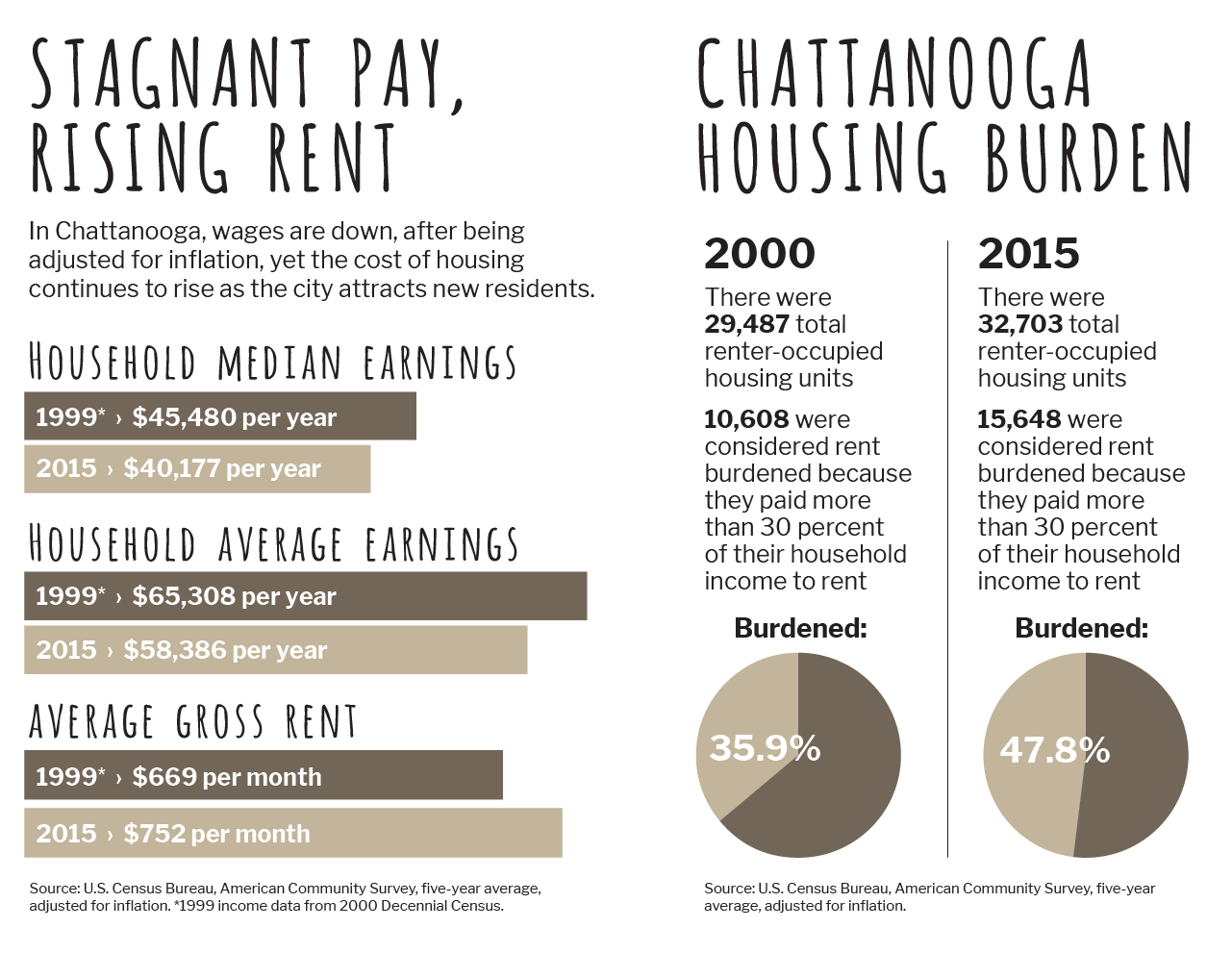

Minority and working-class families with roots in the city were suffering, an abundance of research proved. Housing costs were rising, contributing to a severe shortage of affordable housing. Public schools were failing to prepare a majority of children to make a living wage. Poverty was growing among all races, and few born into poverty were finding a path out. Violent crime was escalating alongside this sense of economic desperation.

And worry over this emerging narrative was giving rise to heated public conversations about housing, economic policy, police tactics and the persistence of racial inequality. Where were the solutions, many wondered aloud at a panel discussion hosted at UTC in March 2016. Where was the leadership, those in the crowd asked of the mayor, the councilman, the chief of police and other community leaders present. Where was the vaunted Chattanooga Way?

“I hate to get biblical,” said Lakweshia Ewing, a 37-year-old entrepreneur, leaning forward in her chair onstage and speaking with the certainty of an Old Testament prophet. “But where there is no vision, the people perish.”

The words struck Cooper, who was sitting quietly in the crowd.

There had been a grand vision, in the beginning at least, she thought to herself, remembering when she herself was 30-something, pondering the same proverb.

Cooper, born Eleanor McCallie, was raised in a deeply rooted local family with close ties to Chattanooga’s wealthiest, most powerful citizens. Her grandfather and great-uncle had founded the all-boys McCallie School in 1905, and two of her great-aunts were among the three founders of Girls Preparatory School.

Still, as a teenager, she wanted nothing more than to escape her hometown.

Cooper came of age in the 1960s and 1970s just as anti-Vietnam war protests and the civil rights movement were gaining energy across the county. Like so many baby boomers, she began to see the world very differently than her parents and their peers. The Bible didn’t support segregation and slavery, she firmly believed, despite what so many Southern pastors said, and having been born with a name that mattered, Cooper thought she could enlighten her elders.

So one summer, while home from Agnes Scott College, she took a stand at the church her family had attended for generations when she chose to back a bold idea proposed by fellow church member, Alice Lupton, the wife of Coca-Cola heir Jack Lupton and the sister of well-known banker Scotty Probasco.

At the time, First Presbyterian Church on McCallie Avenue sat in the middle of a working-class, black neighborhood, and the children who lived in the surrounding blocks needed child care after school. Since the church had space and equipment that went unused most of the week, Alice Lupton, who was later instrumental in integrating several downtown day-care centers, thought the church could open to the neighborhood.

It was a wonderful plan, thought Cooper, who asked to join in on a meeting with Ben Haden, then the lead pastor of First Presbyterian. Jack and Alice Lupton’s daughter, also named Alice, attended the meeting as well, with her boyfriend Rick Montague, a liberal-leaning McCallie School graduate from Lookout Mountain who was also home from college and had long been disturbed by his home-church’s stance on race.

Haden, however, said no to the day-care request. There wouldn’t be enough time to sanitize the church for the white children who came on Sunday, Cooper, Montague and the younger Alice Lupton said the church leader told them the day they all met to discuss the idea.

Their hearts fell.

Montague, disillusioned, left the church. The Luptons pulled their membership not long afterward.

And Cooper determined that, after college, she would leave Chattanooga behind. For 17 years she stayed away.

She traveled to Japan, where she taught English. She moved to New York where she worked for Dr. Caleb Gattegno, one of the most influential and prolific mathematics educators of the 20th century. Later, she lived in Northern California, where she worked at the American Friends Service Committee, a Quaker nonprofit.

She finally returned to Chattanooga in the summer of 1981 only because she was between jobs and needed time to plan her next career move. What she saw downtown on the very day of her arrival shocked and excited her so much that she never left again.

Blues legend B.B. King was playing in downtown Chattanooga, Cooper learned after reading a local newspaper on the day of her return to the city in July, 1981. He was one act in Five Nights, a month-long free, open-air Tuesday night concert series being held in the heart of the city.

Attending was a bad idea, Cooper’s father warned. Riots were expected.

Just the year before, five elderly black women had been shot on East Ninth Street by a Ku Klux Klan member who had driven downtown with two other Klansmen intent on terrorizing blacks. Not long afterward, an all-white jury acquitted two of the Klansmen and convicted the shooter of minor assault, and the city erupted in four nights of riots. Blacks protested, and Klansmen threw firebombs at police.

The next year the Ministers Union, a group of black clergy, began pressuring the Chattanooga City Commission to rename Ninth Street, which ran through the heart of the city’s black business district, after Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

But the commission resisted.

T.A. “Tommy” Lupton, Jack Lupton’s second cousin, had decided to develop two office buildings downtown at a time when no one else would, and both were on Ninth Street. He was fine with East Ninth Street being renamed after the civil-rights leader, the white businessman told city commissioners, but not West Ninth Street, where his buildings stood. When white city commissioners sided with Lupton and his supporters, those pushing for the renaming took to the streets.

That April, just months before the Five Nights concert series began in July, hundreds of protesters, armed with ladders, marched down Ninth street singing “We Shall Overcome.” They pasted green bumper stickers that read “Dr. M.L. King Jr. Blvd.” on street signs and utility poles as police looked on.

Still, Cooper wasn’t afraid to attend the B.B. King concert that night in 1981. She was curious.

She never imagined she would come home and find a crowd downtown as the sun set. For the most part, the heart of the city completely emptied at night. It was hard to imagine a diverse mix of people, white and black, white collar and blue collar, attending anything together.

Yet, there they were, pouring into a vacant lot between Broad and Market streets where the EPB building now stands.

Cooper can remember senior citizens sitting in lawn chairs, bouncing babies on their knees, and others resting on the curbs. Many stood, as well, feeling a restless excitement.

Maybe Chattanooga was actually changing, she thought.

“At last,” she allowed herself to hope.

The road to Five Nights, Cooper later learned, began with the 1977 death of Cartter Lupton, the second-generation owner of the country’s largest Coca-Cola distributor. He had left behind a $200 million estate, which, at the time, was the largest ever probated in the South.

His son and heir, John T. “Jack” Lupton, had no intention of running his family’s business or his family’s foundation, then called the Memorial Welfare Foundation, the way his father had. For years, the majority of the foundation’s funds had supported Chattanooga’s private schools and hospitals, but Jack Lupton wanted a blank slate, his letters show.

Chattanooga faced enormous challenges in the 1980s, and rather than retreat to “little bitty conclaves” where “nobody communicated with anybody,” like his father, Jack Lupton said he wanted to find and fund solutions with the foundation’s holdings, which grew from $35 million to $85 million after Cartter Lupton’s death.

“They wanted to keep this place a secret. They didn’t want anybody knowing about what a nice little deal they had here,” Lupton told a newspaper reporter in 1986, criticizing his father and his father’s peers. “Well, they were full of s—-, as far as I’m concerned.”

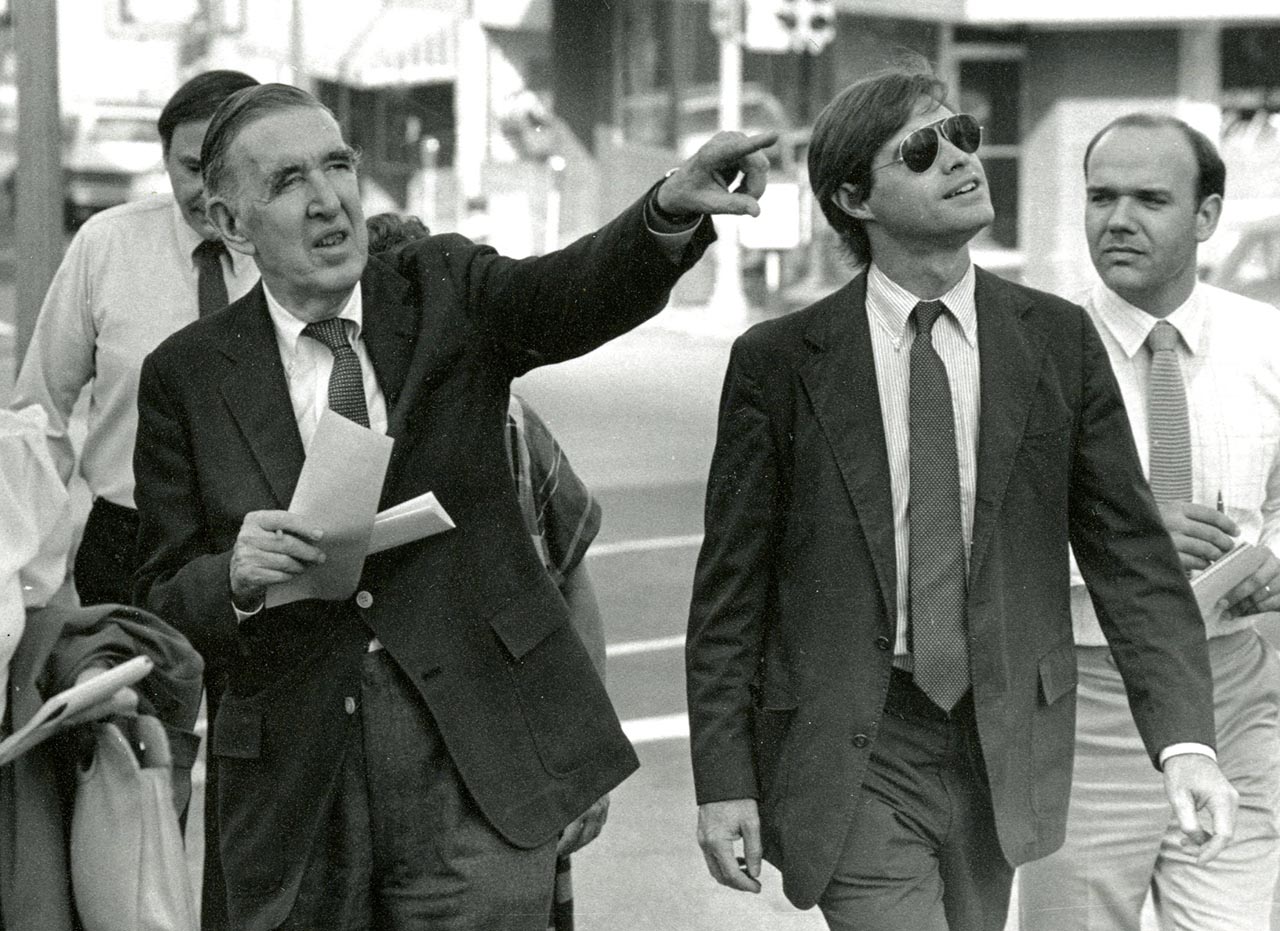

Montague, who had married Jack Lupton’s daughter, Alice, in 1968, right after graduating from the University of Virginia, was tapped to head the foundation, which was renamed Lyndhurst after the razed mansion the Lupton family had owned in the Riverview neighborhood. Before the appointment, Montague had been teaching English at Baylor School.

Progressive and outspoken, he wore tennis shoes with his sport coat to important meetings, and his passion for civil rights, paired with his access to Jack Lupton, left many traditionally minded elites unsettled. The city was plagued by inequality, and the children of poor and working-class families, black and white, were being cut off from opportunity, Montague had learned as a scoutmaster and later as a board member of the Boys Club. The needs and disparities demanded action, he believed.

Jack Lupton, without dictating specifics, demanded creativity and risk taking of his son-in-law.

“If we’re succeeding at everything we do, then we haven’t been taking enough risk,” Lupton told Montague.

So Montague, determined to impress Jack Lupton, resolved to learn the ins and outs of running a family foundation as quickly as he could. On the foundation’s dime, Montague attended conferences and training sessions across the United States, and over a few years he built a team of promising advisers.

Jack Murrah, an English teacher who had worked alongside Montague at Baylor, was hired as a Lyndhurst associate. Montague and Murrah shared many intellectual interests, including an obsession with James Joyce’s short story “The Dead.” The story asked questions they both wrestled with as they grew older. What is the nature of selfless love? What is its impact, even after the grave?

In other ways, Montague and Murrah were different. Montague, raised amid privilege, was relentlessly optimistic and tended to run impulsively with any idea that excited him. Murrah, on the other hand, was soft-spoken and deliberate. Despite growing up in a working-class family in Clanton, Ala., Murrah had gained entry to Vanderbilt University, where he displayed great academic prowess before earning a graduate degree from the Middlebury Bread Loaf School of English.

Meanwhile, Gianni Longo, a fiery Italian immigrant who lived and worked in New York City at the Institute for Environmental Action, became another important ally to Montague and Lyndhurst.

While attending a National Council on Foundations meeting in Seattle, Montague picked up a book co-written by Longo called “Learning from Seattle.” He was so struck by the book’s message that he called Longo when he returned home. After receiving board approval, Montague commissioned Longo to do a study of Chattanooga.

Longo’s report, completed after seven months of intensive study, revealed the guiding logic behind Five Nights.

Pollution wasn’t the city’s main problem in the early 1980s. Thanks to the mandates of President Richard Nixon’s Environmental Protection Agency, the smog — famously cited by Walter Cronkite more than a decade earlier when he called Chattanooga “America’s dirtiest city” on network news — had abated. The big question for Chattanooga was growth. Newcomers weren’t moving in and the educated children of native Chattanoogans, both black and white, were fleeing. Meanwhile, the manufacturing-based economy remained in freefall.

And the greatest roadblock to growth, the cancer killing Chattanooga, argued Longo in his 1980 report, was the city’s deep and historic divisions.

Chattanooga was rife with conflicts — city versus county, small business versus corporation, old versus young, black versus white, worker versus manager and newcomers versus native — that continually stalled and foiled efforts to address problems. There was also a bitter hopelessness that had set in, according to the Longo report, especially among poor and minority residents who had little say in city government. For example, commissioners were elected “at large,” not by districts, a system that ensured majority white rule.

Conspiracy theories ran rampant, fueling anger, and leaders made matters worse by failing to communicate with citizens, opting instead for closed-door decision making, the report concluded. The city was rigged, many told Longo, run by a few individuals and powerful families who made decisions to benefit themselves.

A reknitting had to take place, Longo told Montague after delivering his sober findings. When trust was lost, community planning became an impossible endeavor.

That was where Five Nights came in. A free, open-air concert series with attractive headliners that could draw a diverse crowd might help leaders and citizens see the city and themselves in a new light, Longo said. Similar events had worked elsewhere.

The night of the first concert, Montague paced the streets around the once empty parking lot. Earlier that day, according to Montague, former Chattanooga mayor Robert Kirk Walker had seen him and grabbed him by the lapels.

“The city of Chattanooga is going to blow up tonight,” he told the 36-year-old Montague. “And I am going to hold you personally responsible.”

Montague kept walking, watching for the chaos so many believed was inevitable. But the moment never came.

He never saw Cooper, who was grinning from ear to ear, in the crowd.

Jack Lupton, who was then busy running a Coca-Cola bottling empire that stretched across the South and West, would prove to be an enigma as events unfolded.

For the most part, records show, he took a hands-off approach to Lyndhurst in its early years, trusting in the direction set by Montague. Yet there were times when he would suddenly and abruptly engage.

“He ruled with an iron whim,” Murrah, who retired from Lyndhurst in 2010 after working there for 32 years, often said of Lupton.

And his moods were as unpredictable as his interests. It was fairly common for people to check in with Clara Lane, Lupton’s longtime assistant, and ask whether he was running hot or cold. No one dared bring up anything they cared about with Lupton on one of his bad days. On his better days, however, Lupton could be exceptionally charming, open and comical, spouting off the kinds of things many wanted to say but that only a handsome multimillionaire could get away with.

“This town is like a bunch of g— d—, inbred Collie dogs,” Montague said Lupton once told the Lyndhurst trustees, his way of poking fun at the intermarriage among the city’s wealthiest families, including his own.

As the plans for Five Nights unfolded, Lupton became concerned over the fight to rename Ninth street as M.L. King Boulevard. His cousin, Tommy Lupton, who was opposed to the renaming, was putting the family name in a negative light, he told Montague privately. Still, always wary of the public spotlight, he didn’t want to criticize him openly. Instead, he asked Montague and Lane, his assistant, to invite a group of local black leaders to their sixth-floor Lyndhurst offices, housed in his cousin’s gleaming new Tallan building.

“This town is like a bunch of g— d—, inbred Collie dogs.”

- jack lupton

What could he and Lyndhurst do to help the black community, he asked the handpicked group, which met privately for several weeks.

Get behind the renaming of Ninth Street, said Irvin Overton, who would later go on to be a top executive at Erlanger Hospital. That was what mattered to the black community, Overton said.

But that was a line Jack Lupton wouldn’t cross. Politics were unpredictable, uncontrollable, and he wouldn’t discuss politics, he told the group.

Lupton was unaware that the concert series his foundation was backing was being seen as a veiled political statement. For that matter, he was unfamiliar with many of the Five Nights acts, including B.B. King.

That July, as the concert series was underway, Paul Clark, one of the white city commissioners who had been resisting the renaming of Ninth Street, called Lupton’s assistant and told her to tell her boss that he had changed his mind. Not long afterward, Clark surprisingly seconded black city Commissioner John Franklin’s motion to rename Ninth Street, and the commission unanimously approved.

Lupton was bewildered. He hadn’t asked Clark to change his vote, despite rumors to the contrary.

Montague, on the other hand, was thrilled.Five Nights began a cultural shift. More than 45,000 people attended the five, free concerts, and experienced downtown as a safe, shared space, just as Longo had hoped.

Next, Montague and his allies worked to build on the momentum.

Lyndhurst had seen the impact young people could have when it funded a series of student-led community health fairs across the rural South. Why not ask young architecture students at the University of Tennessee at Knoxville to help the Chattanooga community envision what a new, shared downtown might look like, Montague thought.

So in the spring and summer of 1982, students recruited by Lyndhurst and mentored by UT-Knoxville professor Stroud Watson held exhibits showcasing their vision, which included the first-ever pitch for a linear park along the Tennessee River, as well as the first pitch for an aquarium on the riverfront.

At the same time, Montague and the Lyndhurst trustees agreed to help fund an Urban Land Institute study of Moccasin Bend, the 600-acre peninsula jutting out into the Tennessee River near downtown, which was underused and being eyed by developers. And the study, also presented to the public in 1982, recommended that the city and Hamilton County let a citizen-led task force decide the fate of the Bend.

The night of the presentation at the Hunter Museum of American Art, Dalton Roberts, the Hamilton County executive, tapped Montague.

“Can I call you Mr. Chairman?” Roberts asked Montague as they waited in a buffet line for food.

Four others — two chosen by the city and two chosen by the county — also were appointed to the citizen task force, which was jointly funded by Lyndhurst, the city and the county.

With a blank slate, it was hard to know where to start. Some among the task force believed economic development should be the sole aim, but Sally Robinson, then the executive director of the Adult Education Council, challenged the group to think about how its work could heal the long-divided city.

To many, some of the city’s most recognizable places invoked pain. Some might walk by the Walnut Street Bridge and see a beautiful, historic gem. Others might imagine the bodies of black men hanging from the steel support beams, accused and sentenced by mobs without due process.

“We need places that are free from history,” Robinson said the first time the task force gathered over dinner at Montague’s home on Lookout Mountain.

The comment struck Montague, who cared far more about laying the groundwork for a cultural upheaval than a physical transformation.

Watson, who struck up a friendship with Montague while working with the UT-Knoxville architectural students, would also shape the direction of the task force. Although the group was tasked with planning for Moccasin Bend, Watson argued the group had the wrong focus if it wanted to bring change to Chattanooga. It was the downtown side of the river that sorely needed attention and planning.

So, after agreeing, the group approached city and Hamilton County leaders and asked to do an about-face. Instead of Moccasin Bend, they wanted to study a 20-mile length of the Tennessee River, from the Chickamauga Dam to the Marion County line, with a linear public park in mind.

With a green light from officials, they launched a national search for a consultant, and after much debate settled on the top pick of Montague and Watson.

Representatives of Carr, Lynch Associates, of Cambridge, Mass., had an approach unlike any other. Their plan, they promised the task force, would be shaped by Chattanoogans, not expert planners and architects, and it would evolve under public scrutiny, not be locked away until the last minute.

“This thing will only succeed if you reach out to all in the community, and if you involve particular initiatives that get to the minority community,” Imani Kazana, the firm’s community engagement expert, told Montague.

She would need help with the outreach, however.

So Montague made a call to an old friend.

Eleanor Cooper jumped at the offer to work with the Moccasin Bend Task Force and quickly began planning outreach with Kazana. Over a three-year period, the two women would arrange 65 public meetings.

Many were held at the Chattanooga Public Library on Broad Street. Others were more intimate. And some were meant to reach minority communities in particular. One gathering was held at a black church, while others were hosted at Kirkman Technical High School, the Bethlehem Center in Alton Park and a community center on the west side of the city.

“What do you want, regarding the Tennessee River?” Cooper and Kazana asked, time and again.

Access to the water, one woman said. At the time, most of the riverbank was blocked by brush and private property, making it nearly impossible to swim or launch a canoe. An elderly black man said he wanted the plans to include safe places to fish. A mother said she wanted a paved walkway so she could push her baby stroller along the river’s edge.

There were tense moments along the way.

At one packed library meeting, a landowner along Suck Creek stood up and asked what was on many people’s minds.

“We just have one question,” he said. “When are you going to take our land?”

Never, answered Steven Carr, one of the consultants who was presenting a working draft of the river park plans. There was no hidden agenda, he said.

Later, American Indians voiced concern over sacred land on Moccasin Bend, fearing it would be violated by future development. The task force responded by proposing a national park to protect the space.

There was also general anxiety about whom the plan would ultimately help. Even Robinson feared that Chattanooga might end up creating a lure for tourists, rather than a place that Chattanoogans could use and enjoy.

Still, as the process unfolded, Cooper and Montague watched in awe.

Longo’s study had painted a grim picture of a city divided and disenchanted, but meeting after meeting illustrated that a new, shared hope was bubbling up. Consensus seemed possible. Community-building seemed possible.

“So many details that were once the discussion of a task force, elements in a plan, ideas on paper, were now tangible objects,” Cooper wrote to Carr several years later, on the weekend the Tennessee Riverpark finally opened. “What we hadn’t imagined was the magic of the sunlight in May, the sound of the birds in the early morning, the reflection of the water in the afternoon, the music of children, black and white, playing together, and the smell of barbecue as families of all races picnicked beside the river. We didn’t even know how much we needed it.”

In the speeches made that day, she noticed that the radical beginnings were already being forgotten, she wrote.

“But there were those of us there,” she said, “who remembered.”

The Moccasin Bend Task Force taught a lesson, those involved believed. There was a better way of doing the people’s business.

And, in 1983, they weren’t alone in questioning traditional approaches to city planning and economic development. Longo was just one consultant in a growing network of national nonprofits and experts pushing leaders of post-industrial cities to begin thinking in new ways.

Groups like the D.C.-based Partners for Livable Places, which hosted a one-day conference in Chattanooga in May 1983, argued that opportunities were flocking to cities that catered, not to corporate interests, but to the interests of residents. Many cities Partners for Livable Places showcased attested that a “quality-of-life” emphasis offered a competitive edge.

Still, this perspective wasn’t shared by those sitting in many of Chattanooga’s top offices.

City leaders, including those at the local Chamber of Commerce, obsessed over recruiting industry and believed it was more important to sell those outside the city than those inside. Coddling a public with a host of differing opinions wasn’t a solution.

Ron Littlefield, then a young, urban planner from Georgia who was working for Dave Major at the Chattanooga Chamber of Commerce, disagreed. He felt the chamber, flummoxed by the falling population and job numbers, should send an envoy to Indianapolis, which had been highlighted at the Partners for Livable Places conference funded by Lyndhurst.

Major wasn’t interested, but Bob McNulty, head of Partners for Livable Places, with Lyndhurst’s backing, was able to rally interest in a visit to Indiana. Forty-seven people — all middle- and upper-class residents from a variety of backgrounds — would end up going on the trip, which was funded by Lyndhurst.

Indianapolis, once called India-No-Place, was a thriving metropolis, and its turnaround, boosters argued, could be traced back to a diverse, 60-member board of citizens called The Greater Indianapolis Progress Committee.

Federal funds for cities began drying up in the late 1970s and were further cut during the Reagan administration. Before the committee was formed, the city was shedding staff and couldn’t afford to fix potholes or meet the funding needs of public schools, but a new bottom-up approach to planning, institutionalized with the creation of the progress committee, had helped turn the tide.

There were social issues the committee addressed such as desegregation and policing, but its main success was bringing the middle class and the private sector into the government’s work, filling the gaps Washington had left them with, those in Indianapolis said. “Public-private partnerships,” as they called them, had saved the day. It could be a slippery slope to commercial control, many would later realize. But then, the approach seemed to reflect America’s highest ideals. Government became open, pliable, and far more efficient.

Tom Hebert, a representative from the Tennessee Valley Authority who went on the trip, was wowed, and he wasn’t alone. Still, Major, then the executive vice president of the Chattanooga chamber, remained unimpressed. He had no intention of returning home and mimicking Indianapolis, he told Hebert.

So, in between sessions, Hebert, frustrated, approached Montague.

“What should we do?” he asked.

Montague walked him to the edge of the auditorium the group had gathered in and pointed to someone in the seated audience.

“See that woman down there?” Montague told Hebert. “That’s Mai Bell Hurley. Talk to her.”

Hurley, who worked as a newspaper reporter for the Chattanooga News-Free Press before marrying Bern Hurley, a Provident Life & Accident insurance executive, exerted enormous influence as a community volunteer at the time, despite the city’s patriarchal culture.

“Can a woman lead?” a United Way board member once asked when Hurley was tapped to head the year’s fundraising drive.

“Mai Bell Hurley can command legions!” a businessman scolded.

Despite being highly educated and politically astute, she feigned humility, often calling herself “the housewife of North Chattanooga,” knowing the great benefit of being underestimated. She was expert at navigating the male-dominated power structure, having an innate sense of when to press and when to pull back.

The lessons of Indianapolis would find no life in Chattanooga without her.

The trip had been inspiring for many, including Hurley, but city leaders simply weren’t interested in the Indianapolis approach. The chamber, under Major’s leadership, had its own economic development plan underway, and, unknown to most, the newly elected city mayor, Gene Roberts, was developing a plan, too. Still, rather than wait and worry, Hurley, Hebert and Montague, who began discussing strategy while in Indianapolis, decided to act.

They would form a committee called the Options Study Group to come up with a better community planning process, they told the city mayor, and to start they invited anyone who had gone to Indianapolis to be a part.

Three middle-class blacks would remain involved. Claudie Clark worked for Coca-Cola. Jerome Page headed the Urban League, and Howard Roddy was then the head of the Chattanooga-Hamilton County Health Department. Bill Evans, a member of the electric workers union, also was recruited to give voice to the labor union perspective. Some, including black City Commissioner John Franklin, would later criticize the group’s lack of diversity. The same, established people were often tapped to represent the black community, while the perspective of poor and working-class blacks was often left out. Still, Hurley felt the mix was right.

The Options Study Group, which met weekly between mid-December of 1983 and mid-February of 1984 would end up studying 11 cities and conclude that those in Indianapolis were right. Cities such as Chattanooga were doomed if elected officials and businessmen continued to map out the future in a vacuum.

The old order had to be upended.

The Options Study Group members felt they knew what needed to be done. Still, it seemed they were too late.

The mayor and chamber, behind closed doors, already had decided how they wanted to address the city’s stagnation, Hurley soon learned. The plan, she heard, was to create a new economic development entity called Partners for Economic Progress and to hire a San-Francisco-based planning firm that could guide their steps.

Infuriated, Hurley confronted Mayor Gene Roberts, who told her not to worry. Just wait and hear the perspective of the San Francisco firm, he insisted.

The group was well aware of the San Francisco approach, however, thanks to Montague, who had studied San Francisco during months of research.

In San Francisco, the planning — directed by the very firm the city and county executives wanted to hire — had been top-down, not bottom-up as it had been in Indianapolis, Montague found. The problems chosen to address were handpicked by the business community and the process had been controlled by the private sector, which had ignored issues such as crime and social welfare. The community voice was completely left out. In Chattanooga, where there was so much suspicion of the “power structure,” an approach like that couldn’t work, the group concluded.

Their concerns didn’t gain currency, though. A few months later a Chattanooga News-Free Press article announced that 36 corporate leaders, all white heads of major banks and businesses, were backing the chamber initiative.

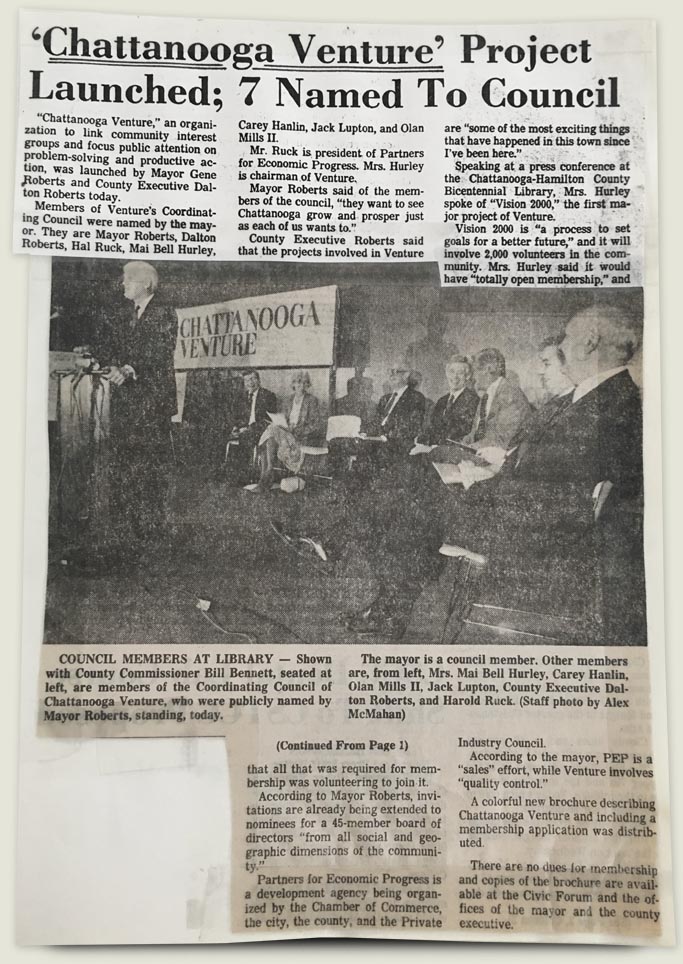

Still, the Options Study Group members kept working on an alternative plan until, finally, they stumbled onto an approach they thought could work. They would form an independent 501-c-3 organization, and they would call it Chattanooga Venture.

And its first order of business would be a communitywide planning process unlike anything the nation had ever seen.

Montague should deliver the message, the group agreed. With the backing of Lupton and Lyndhurst, he could safely negotiate with the powers behind the economic development plan and be taken seriously.

“Slow down … long enough and hard enough to realize the benefits and opportunities presented here,” he wrote the mayor.

Both initiatives could work together, Montague proposed.

“I don’t think that economic development without wide community vision, participation and leadership will work,” he added. “Unless the two arms embrace each other, trust each other, listen to each other and balance each other, the $3.5 million effort at economic development will be (another) failure.”

A third organization, one that could mediate between a chamber-backed plan and a community-backed plan, could be the solution, he argued.

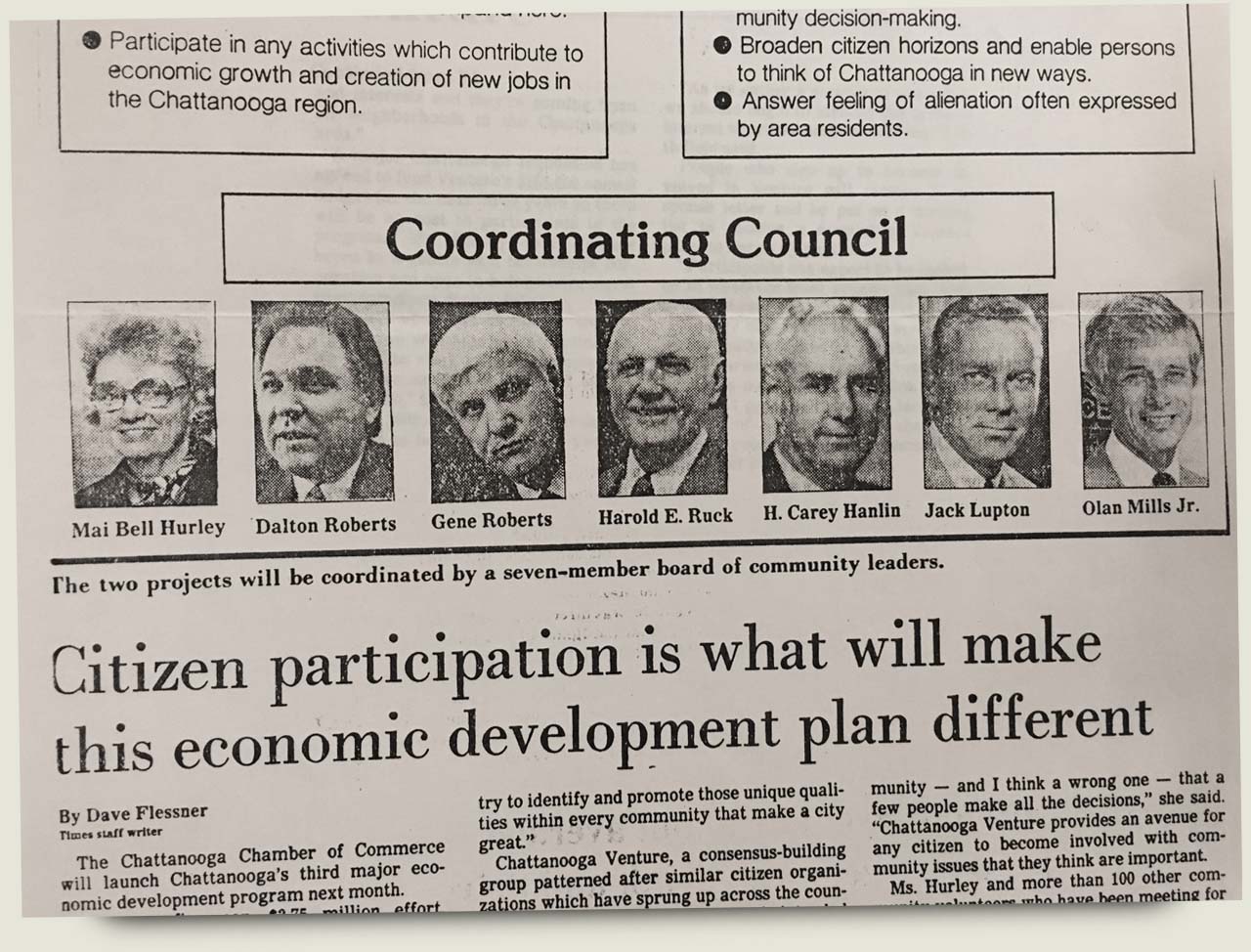

This “super board,” as he called it, would consist of seven people: The mayor, the county executive, the head of Partners for Economic Progress, the head of Chattanooga Venture and “the three most powerful corporate chairmen in the city who are known for their broad vision and experience, effectiveness, trust, openness and ability to listen.”

It was a power play. The key was to leverage Jack Lupton, who, once involved, could tip things in favor of Chattanooga Venture. City leaders saw Lupton as a rare, big fish, impossible to net. He didn’t like publicity. He didn’t like drama. But a link to him and his resources could prove invaluable. This was a way to get their hook in, and Hurley and Montague knew it was a pitch few politicians could resist. And they were right.

The offer was accepted.

Montague asked Jack Lupton to sit on the Coordinating Council, as it was formally named.

Hurley approached H. Carey Hanlin, the CEO of Provident insurance, where her husband worked, and together they convinced Olan Mills, a Democratic fundraiser and photography business magnate, to play a part as well.

The presentation by the San Francisco-based firm was canceled, and there was a standing-room-only crowd at the next Options Study Group meeting, which Hurley opened to applause.

She would be the first chairperson of Venture, a radically open organization with free membership that would be solely funded by Lyndhurst and controlled by the largest and most diverse board the community had ever seen. Littlefield, who by then had been fired from the Chamber, would be its first executive director.

It was a huge victory for the everyday Chattanoogan, they all believed at the time.

To Montague and Hurley, Lupton represented a known quantity, a democratic force, a protector. He had always wanted things to be done differently in Chattanooga. This was his chance.

Those on the outside, however, couldn’t separate him from the Lookout Mountain mythology, from the image of wealthy men, born into money they didn’t earn, deciding the fates of companies and cities from inside private clubs, isolated from the impact of their decisions. Lupton was so private, always denying requests from the media and fiercely guarded by those inside his bubble, that the average Chattanoogan couldn’t guess at his motivations for involvement.

But really, no one, not even Montague, could predict his actions, and that would become clear in the years to come.

“What kind of city do we want Chattanooga to be?”

That was the question Chattanooga Venture would take to the public.

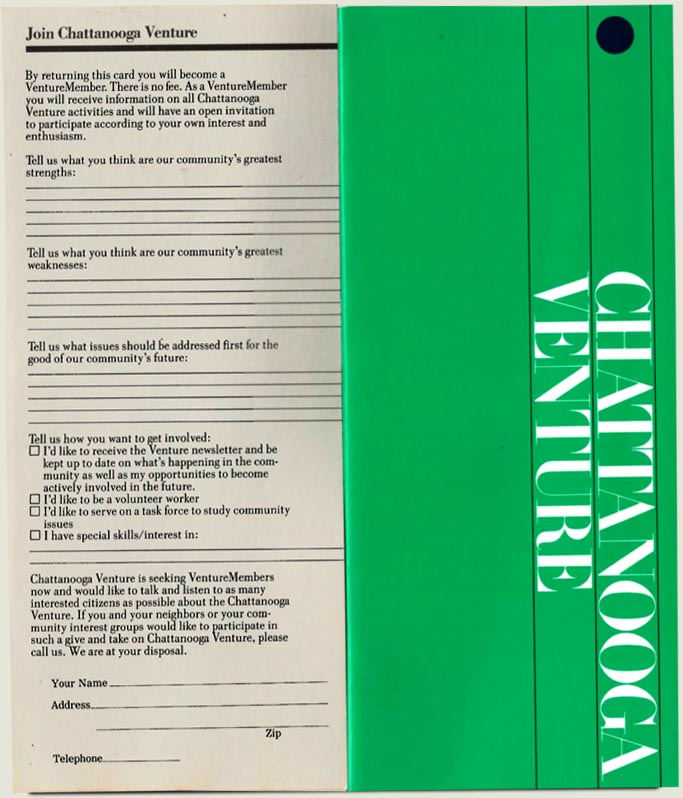

Pat Wilcox, a Chattanooga Times writer who had volunteered with Venture, hurriedly worked with others on a brochure, an invitation to the citizen-led revolution they believed would save their city.

“Chattanooga Venture heralds a new day in the way decisions will be made. A new day of community based leadership,” they wrote.

They described Venture as an open association of citizens, a channel for the exchange of information, a means to focus the collective energy of the community and a tool for solving problems and setting a direction for the future.

Years later, reading the words of that same brochure would bring sadness.

“I don’t know how many people shared my view,” Wilcox said in 2012, when Cooper interviewed her for her dissertation. “I expected it to be a permanent thing. It didn’t turn out that way.”

It was Chattanooga, after all, a place where even the geographic grandeur whispered that there were those above and those below, those that mattered and those that did not.