As the downtown tour went on, the story — told by area business leaders and boosters — started to sound scripted.

Each narration of Chattanooga’s turnaround began the same way.

“In 1969, on the evening news, Walter Cronkite called Chattanooga the dirtiest city in America,” another city leader told the group that had flown to Chattanooga from western Massachusetts in the fall of 2015.

The racial conflicts and divisions that plagued the city in the early 1980s weren’t mentioned. Neither was the unprecedented effort to topple Chattanooga’s longstanding culture of top-down decision making that favored businesses.

So, that night, after the group’s tour and meetings had concluded, the visitors from Massachusetts sat together and discussed what they had seen and heard. Marcos Marrero, the economic director of Holyoke, Mass., was one of the first to speak up.There was something about the rosy renaissance narrative that seemed off, he said. When they asked locals about the quality of the local public schools, they were told the Hamilton County school system was troubled. Where were the community’s black leaders? His companions had the same questions.

The Chattanoogans they met boasted of bold leadership and risk-taking, as well as strong “public-private partnerships.” Still, they weren’t bowled over by the beautiful city or its highly advertised, but loosely defined, “Chattanooga Way.” On first impression, Chattanooga seemed like so many other cities in America: Just one more place where serious political and economic problems hid beneath a veneer of artisan restaurants and new construction.

And, to a large extent, they were right. Studies were continuing to show that Chattanooga was, in fact, two cities, growing further apart, perhaps destined for collision in the years to come.

For example, one study released in early 2017 by the personal finance website Magnify Money showed Chattanooga was one of the best places in the country to live for those earning more than $100,000 a year. Another study published by researchers at Harvard University and the University of California-Berkeley, however, showed Chattanooga had some of the worst economic mobility rates in the country.

Like many, Marrero and his colleagues had come to Chattanooga in search of solutions to economic problems. Yet, they were also looking for innovative approaches to America’s stickiest problems: generational poverty, limited economic mobility and worsening class and race-based segregation, factors they knew threatened growth in the long term.

Hadn’t there been a people’s movement in Chattanooga, a vision, they wondered. The widely publicized story of Chattanooga’s citizen-led planning process had, in part, drawn them to the Scenic City. Where had that led? Did Chattanoogans feel, as advertised, a shared sense of power and hope?

They had no idea where to turn for answers.

The original renaissance architects had passed the torch to new leaders. Coca-Cola bottling heir and iconoclast Jack Lupton, whose family fortune gave life to the Lyndurst Foundation, RiverCity, the Tennessee Aquarium and Chattanooga Venture, among many other things, had died. So had Mai Bell Hurley, the political juggernaut who helped secure the state funding that set downtown’s physical transformation in motion. And those who were still alive were in their late 60s and 70s, long retired, weary of public life and mostly forgotten.

Greg Richane, another member of the Massachusetts group, turned to Google.

He typed a string of words: “Social justice. Equity. Chattanooga.”

On the top of the page, one site stood out. Chattanooga Organized for Action — a grassroots group that, in recent years, has raised questions about discriminatory banking practices, as well as local affordable housing policy — seemed to offer the other side to the Cinderella narrative.

“It might come as a surprise to some that there are two Chattanoogas,” the website read. “A city of opportunity for some, and a city where the gravity of poverty gains a stronger grip.”

It was after midnight, but Richane pulled up his email and began typing a request to Michael Gilliland, the 36-year-old volunteer leader of the nonprofit organization who worked full-time as a restaurant manager in the Bluff View Art District.

“Help me bring the whole story home.”

Gilliland, awake, wasn’t shocked by the note. After all, it wasn’t the first. It also wouldn’t be the last.

The Tallan Building loomed over M.L. King Boulevard as the group of Covenant College graduates gathered in late April of this year and waited for “The People’s History Tour” to begin.

It would be one of several narrated walks across the city that year, led by Gilliland and Jefferson Hodge, another young volunteer with Chattanooga Organized for Action. In the two years since connecting with the group from Holyoke, Mass., Gilliland had received numerous requests for information about the city’s history from those who felt dissatisfied by the shorthand, booster-backed version. An increased media spotlight on local problems related to poverty, crime, housing and education had revived interest in the city’s past.

Gilliland and Hodge started the tour on M.L. King Boulevard for a reason, they told the recent college graduates. Leaders are willing to admit to a polluted past. Yet Chattanooga’s long history of race and class conflict are brushed under the rug, they explained, before educating the group about the 1980 Ku Klux Klan shooting of five black women downtown, as well as the 1981 fight to rename Ninth Street as M.L. King Boulevard.

“If we don’t tell the accurate story, we’re never going to be able to address the problems we are now facing,” Gilliland said.

To Gilliland and Hodge, Chattanooga Venture, the nonprofit that jump-started the city’s turnaround, wasn’t even worth mentioning. Among the leadership class, there had never been genuine interest in the needs of poor and working-class Chattanoogans, they told the students that day.

It was a take on history that both Rick Montague, Lupton’s one-time son-in-law and the former head of Lyndhurst, and Eleanor Cooper, the last director of Venture, had feared. More than 30 years ago, they had believed — thanks to a groundswell of local support and a flood of outside praise — that they were standing at the center of a revolution that taught change and consensus were possible in a polarized America.

Cooper wrote Montague in 1990, just a few years before Venture faded away: “My goal, or one sign of whether we have been successful is that when we are Mai Bell Hurley’s age, there are lots of players, lots of diverse players, diverse in age, race, sex, location of residence, economic status, etc. Lots of ‘us’ making decisions, leading up progressive efforts, raising money, donating money and getting the glory,”.

Today, that vision still proves elusive.

City leaders assert Venture and its visioning experiments, Vision 2000 and Re-Vision 2000, left a lasting legacy.

“Today we do it so often it’s in our DNA. It has its own name, it’s the Chattanooga Way,” RiverCity President Kim White told a group of University of Tennessee at Chattanooga students during a presentation in 2014.

In some ways, she’s right. It’s nearly impossible to find a local initiative that doesn’t boast some form of citizen engagement. “Nominal group technique,” the formal name for the process Chattanooga Venture used during Vision 2000 and Re-Vision 2000, continues to be used by area organizations and consultants, albeit in much smaller settings.

Still, those who’ve studied Chattanooga’s turnaround say the Chattanooga Way, or the Chattanooga process, as academics call it, was cast aside decades ago.

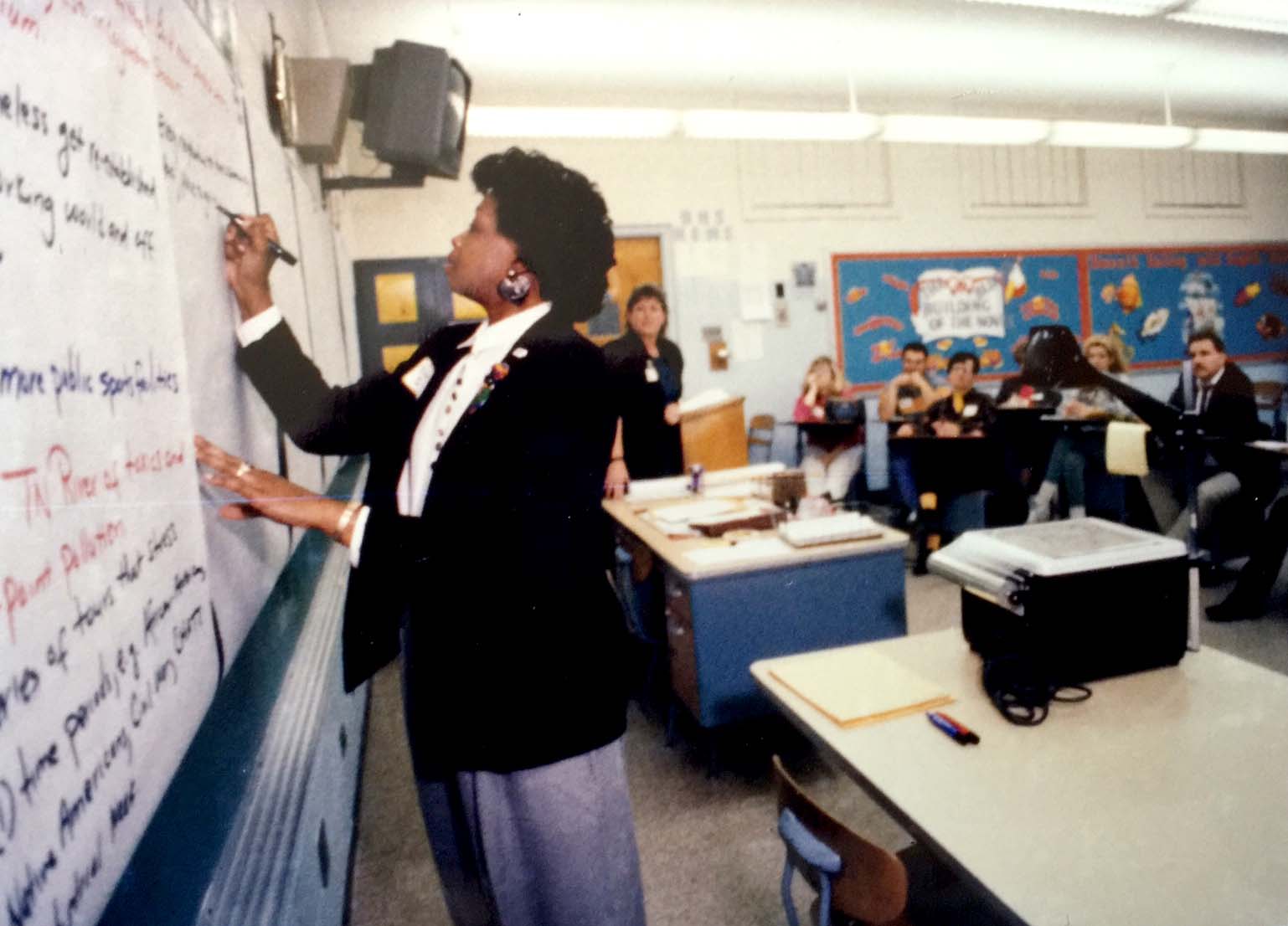

In the 1980s and 1990s, Venture took a radical approach to community planning. Instead of asking the perceived best and brightest to chart Chattanooga’s future course, Venture leaders went to the general public without an agenda, records show, and asked every member of the community to build and refine the city’s goals.

This degree of engagement, which required enormous trust in the wisdom of diverse groups and highly skilled facilitation, simply doesn’t exist on the scale it once did, argues Storm Cunningham, a redevelopment expert who studied Chattanooga for his book “reWealth!”

The private, nonprofit RiverCity, for example, only vets larger projects with the public after they are conceptualized and nearly ready to go. Leaders today, he said, ask more for approval than engagement.

These days, there is no shared vision for the future of Chattanooga, just a host of different groups engaging people in different ways and spinning off their own ideas about the future, informed largely by academics, experts, business leaders, politicians and foundation boards, he said.

Others who’ve studied Chattanooga agree with Cunningham’s assessment.

“Local democratic participation tended to become more and more mirage or smokescreen for elite manipulation and control,” wrote Ernest J. Yanarella and Robert W. Lancaster in “Getting from Here to There?: Power, Politics and Urban Sustainability in North America,” after studying Chattanooga’s turnaround.

In the meantime, local political, economic and racial polarization has worsened, making a consensus on local problems and solutions seem more improbable than ever.

Of course, Chattanooga is not alone. Academics have been warning about the disintegration of community adhesion since the 1970s, pointing to falling trust in major institutions and dwindling membership in civic clubs and churches. A host of factors, including the advent of the Internet and social media, have driven Americans into isolated pockets, experts say. The divide seems to have deepened since the 2016 presidential election.

Still, Venture pushed back on the trend for a time and shouldn’t have been killed, Cunningham said.

Cities need “renewal engines” such as Venture, Cunningham argues, because they serve three important and distinct purposes that fuel progress. They create and house a shared vision of the community’s future. They foster buy-in and culture change, and they provide a neutral ground for partnering.

“They had no way of knowing how crucially important it is to keep visioning, culturing and partnering processes together in one organization, and for that organization to be seen as being of the people, run by the people, for the people,” wrote Cunningham.

On the other hand, White, who has been at the helm of RiverCity for eight years, says she doesn’t think the city needs another round of communitywide visioning or an organization such as Venture. She believes the right stakeholders need to continue to work together to tackle the city’s next set of challenges.

“It’s really about getting the right people in the room,” she said. “Today you can’t just say, let’s do whatever you want. It’s a lot more granular now. It’s not just asking a group of citizens what they want to enact. It’s more difficult to have a Venture.”

Chattanooga Mayor Andy Berke, now serving a second term, said he also doesn’t see the need for a community vision or a Venture. The public hasn’t asked for such an approach, and his administration does a good job with civic engagement, he added.

“We do community engagement every day. That’s an essential part of what I do … part of my job is listening,” said Berke. “It informs the decisions I make every day.”

In recent years, however, more and more have cited a disconnect between the agendas of leaders and the needs of citizens.

“You call it Gig City. African-Americans call it rigged city,” said the late community activist Joe Rowe, who along with a group of downtown property owners called on the city to suspend a controversial tax break program that Berke had revived in 2014.

Others were frustrated when public feedback was discarded after meetings in 2016 to determine how much parking developers were required to build to accommodate new housing.

“Some remembered the ‘good old days’ of Chattanooga Venture: openness, transparency, productive community discussions held in good faith,” Franklin McCallie, a Southside retiree, wrote in an editorial to the Times Free Press.

Community members voiced similar frustration with Berke’s Violence Reduction Initiative, which was built by experts outside of Chattanooga without much public feedback.

“We stand before you today as the voice of the voiceless, the voice of those whose voices have fallen on deaf ears and whose deeds are not recognized in city hall and the chambers of justice,” said local Nation of Islam minister Kevin Muhammad, who spoke to city council members in 2016 before a packed audience who had come to city hall to support his speech.

It’s a bad omen for the future, Cunningham warns.

Cleveland, Ohio is a perfect example. Much like Chattanooga, Cleveland faced environmental embarrassment in 1969 when oily slime on its Cuyahoga River caught fire. And, much like Chattanooga, Cleveland, a former industrial town with a waterfront, became known for civic efforts that brought it out of crisis. But the public-private partnerships forged during that era fell apart in the early 2000s.

According to Cleveland State University economist Ned Hill, who studied the unraveling, the shift occurred with the emergence of a “less democratic, top-down community planning process that was driven almost exclusively by the city’s business elite.”

Cooper never intended to grow old in Chattanooga, a place she had considered narrow-minded and wedded to the past.

But her friend Montague changed that when he took over Lyndhurst, at the request of Lupton, and began pushing city leaders, with the help of allies like Hurley, to begin thinking in new ways.

In the 1980s, from her perspective, the city was surging with energy and excitement as partnerships, trust and confidence were built, first through the work of the Moccasin Bend Task Force and then through Venture.

Later, after Venture was killed by some of the very people who created it, doubt and skepticism set in. Perhaps Hurley was right. Maybe Venture had served its purpose and needed to die, Cooper thought at times.

While innovative, Venture was clearly imperfect. It lacked a diverse funding base. Nonprofits can rarely, if ever, rely on everlasting funding from a single foundation. It also lacked a large degree of racial and economic diversity, especially in its early years. Eventually, its influence began to wane as its most powerful members lost interest in its mission.

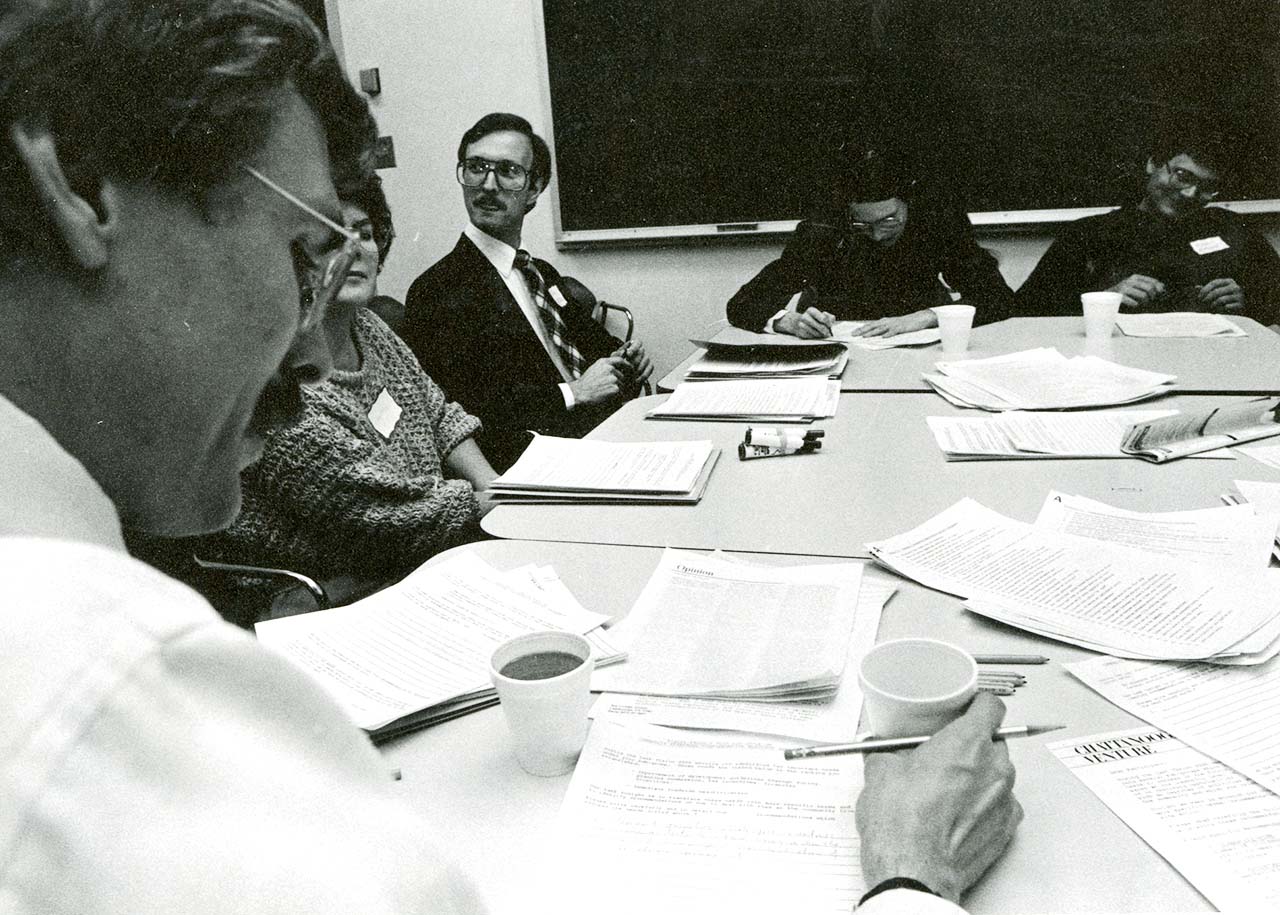

Yet, after enrolling at UTC in 2008 and spending five years studying the early years of Venture for her doctoral dissertation, Cooper came to some of the same conclusions as Cunningham. Perhaps the Venture experiment could teach something to cities facing big challenges in the midst of growing polarization.

There was a reason traditional civic engagement models often led to little public buy-in.

For people to care and act, they need to feel connected. And Venture, in the beginning, at least, created connections that didn’t exist before, Cooper said.

It created a community of people who, as Hurley often said, wanted to be “hopeful and helpful.” People didn’t just show up to a lecture and leave. They brainstormed. They learned from one another.

At each step of the visioning process, participants were given equal weight and equal control of the process. Those running the meetings weren’t there to convince others to oppose or support anything. They were there to listen and moderate. Everyone’s ideas, big or small, were recorded. And then the long list of ideas gathered from the public was presented to the public, members of which voted on which ideas they thought should be top priority.

It’s an approach that can still make the impossible seem possible, Cooper believes.

“Learning plus connection equals vision,” she wrote in the conclusion of her dissertation. “Vision not only drives change but it also builds community. It has a multiplier effect.”

These days, Cooper hopes a new generation, looking to innovate in the realm of civic engagement and consensus building, will care enough to learn from the city’s past and build on her generation’s successes and failures.

Others agree that renewal is needed.

“I laud Chattanooga for what they have accomplished but fault them for not looking ahead for a set of new challenges, new issues of today, that need to be addressed with vigor, originality and innovation,” said Bob McNulty, founder of Partners for Livable Communities, the organization that introduced Chattanooga to the idea of public-private partnerships in the 1980s.

Gilliland, who has been working since graduating from UTC to get local leaders to acknowledge and address the plight of working-class Chattanoogans, was born in Red Bank in 1981, just as Montague and Cooper were beginning their work.

Still, while Gilliland admits Chattanooga is far more attractive than it was when he was growing up, he has never felt pride in the renaissance narrative of his hometown. To him, the city’s story is told and retold simply to benefit Chattanooga’s rich and powerful, who are poised to benefit from surging interest.

Like many, he never knew much about the motivations behind Venture. Those with money and influence eventually abandoned the program. So he assumed its big talk about changing local culture and giving voice to all Chattanoogans had never been genuine.

Over the years, though, he found other local stories that did move him. The fights, some won and some lost, for workers’ rights. The black attorneys who argued for due process in the face of mob violence. The civil rights protests. The federal cases, instigated by everyday citizens, that forced government to change.

“Those are the more inspiring stories,” he said.

And they led him into community organizing and activism, he said. They taught him that history doesn’t just bend for the Jack Luptons of the world. Ordinary people who share a vision can change the course of a city, too.

The Venture era was certainly not the first time Chattanoogans had organized and fought to be heard, although it may have been one of the only times the fight was endorsed, to a certain degree and for a short period, by those with money and power.

“I believe in democracy and consensus, the best of what Venture hoped for,” Gilliland said.

Venture may be dead, and the memory of it long faded. Still, its original call for a diverse city to come together and cast a vision for the future is relevant, especially today, Gilliland said.

And he and many others are working to make it happen, again.

In Nashville, a group called Nashville Organized for Action and Hope has made impressive strides organizing community groups and building consensus around issues such as affordable housing. Turnout in the most recent mayoral election significantly spiked, thanks in part to the group’s work, news articles show.

“I BELIEVE IN DEMOCRACY AND CONSENSUS, THE BEST OF WHAT VENTURE HOPED FOR.”

- MICHAEL GILLILAND

While its efforts have been stalled at the legislative level, its success engaging the community offered hope to Gilliland and others, who have seen many efforts to address local problems fail to arouse action.

So, in September of 2016, a handful of Chattanooga Organized for Action members, local union members and local clergy formed Chattanoogans in Action for Love, Equality and Benevolence and began working with the Gamalial Foundation, the faith-based nonprofit in Chicago that trained the group in Nashville.

In the past, Gilliland said, Chattanooga Organized for Action had never reached out to churches or asked their congregants to engage in local social and political issues, but Gamalial challenged the Chattanooga nonprofit to begin building bridges. Gilliland is learning more and more, he said, that a successful movement requires partnerships across race, class, age, geography and political parties.

Since last fall, organizers of the new grassroots nonprofit, through one-on-one meetings, have been working to build a coalition of 20 organizations that can begin meeting to discuss a vision for the future of Chattanooga. At publication, eight organizations, including several black churches, had signed on.

They don’t know what will bubble up from their efforts, Gilliland said. Those working to create a critical mass of interested groups aren’t setting an agenda, right or left, much like the first leaders of Venture. They want the agenda to come from the whole, as the whole learns together and builds trust and community.

But, unlike Venture, the group isn’t courting the rich to fund their efforts.

It’s a risk. Without big names and big foundations and big money, many will say their efforts are doomed. Gilliland knows that much is true.

Still, there is a sense among the group that anything is possible. Just like those who toiled to birth Venture, those working to grow a new grassroots planning movement want to help the city avoid a damning crisis and offer real hope to communities that remain bitterly divided and politically log-jammed.

Along the way, those leading this new effort may be burned by their ambition, said Montague, reflecting on his own efforts decades ago. They may fail. Or they may succeed. Regardless, though, they must care, he said, and they must try, no matter how daunting the feat.

Such audacity has always found fertile ground in this breathtaking river valley. Perhaps, in many ways, this boldness is the true Chattanooga Way.

“Maybe the secret is, to hell with the story,” said Montague. “Start over!”

“We want to have a community that is informed and inspired by history, but not a slave to it.