The dream began in the middle of a scene.

Eleanor Cooper was hanging from a second-floor balcony, choking on fear, and below her, the contents of her purse had spilled onto the ground.

“Help,” she whispered, afraid to draw attention to the valuables that could have easily been taken right from under her.

Several friends were nearby. They could hear her plea, but they didn’t respond.

“All that is valuable to me has been dropped,” Cooper typed in a journal after she woke that morning in September 1993, documenting the nightmare. “I can’t do anything about it. And I can’t scream.”

“I am left hanging.”

It was a metaphor, she realized as she wrote the scene. She felt abandoned. But more than that, she felt something precious to the city had been lost, maybe forever.

In the real world, Cooper had just said goodbye to Chattanooga Venture, the revolutionary, citizen-led nonprofit organization credited with jump-starting Chattanooga’s remarkable rebirth in the last decades of the 20th century. As she pecked at the keys of her computer, the loss finally set in.

She wanted to hold on to what she and hundreds of others had helped build but ultimately she couldn’t save it.

It seemed very few wanted to continue pioneering an approach to civic engagement that could teach a lesson to the world, despite the strides that had been made. Venture had served its purpose, some of the very people who had once argued for its permanence would say. It had given birth to an extraordinary story, as well as new dreams of growth and development, far beyond what anyone had imagined possible. That was enough.

What was left of Cooper’s own vision, however, was grief, a sadness that would remain, festering in the corners of her mind for decades.

A decade before the grief, however, there was great excitement.

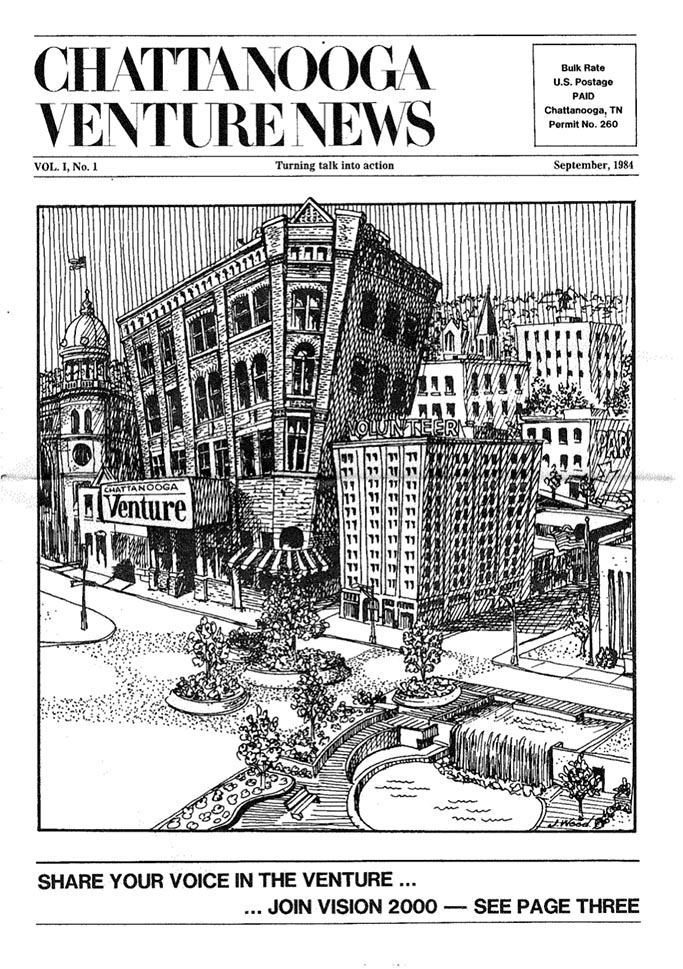

Few in or outside the movement to change Chattanooga’s culture of top-down decision-making knew what to expect when Venture launched in the summer of 1984, asking Hamilton County residents: “Would you like to have a greater role in the future of Chattanooga?”

For so many years Chattanooga’s future had been mapped out in the halls of the tony Mountain City Club. Citizens, cynical and frustrated, believed there was little hope for reform, studies had shown.

Still, many responded with a resounding yes to Venture’s call.

“The most exciting thing is that they welcome anybody and everybody,” a special education teacher from Red Bank gushed to the reporter the day of Venture’s grand opening at the old Ross Hotel on Georgia Avenue.

“This country started with civic involvement. Venture is beginning to draw people back into the workings of their government,” a contractor said the same day.

A high-school counselor called Venture “the best thing invented since the wheel. It will hopefully help get this community out of the doldrums.”

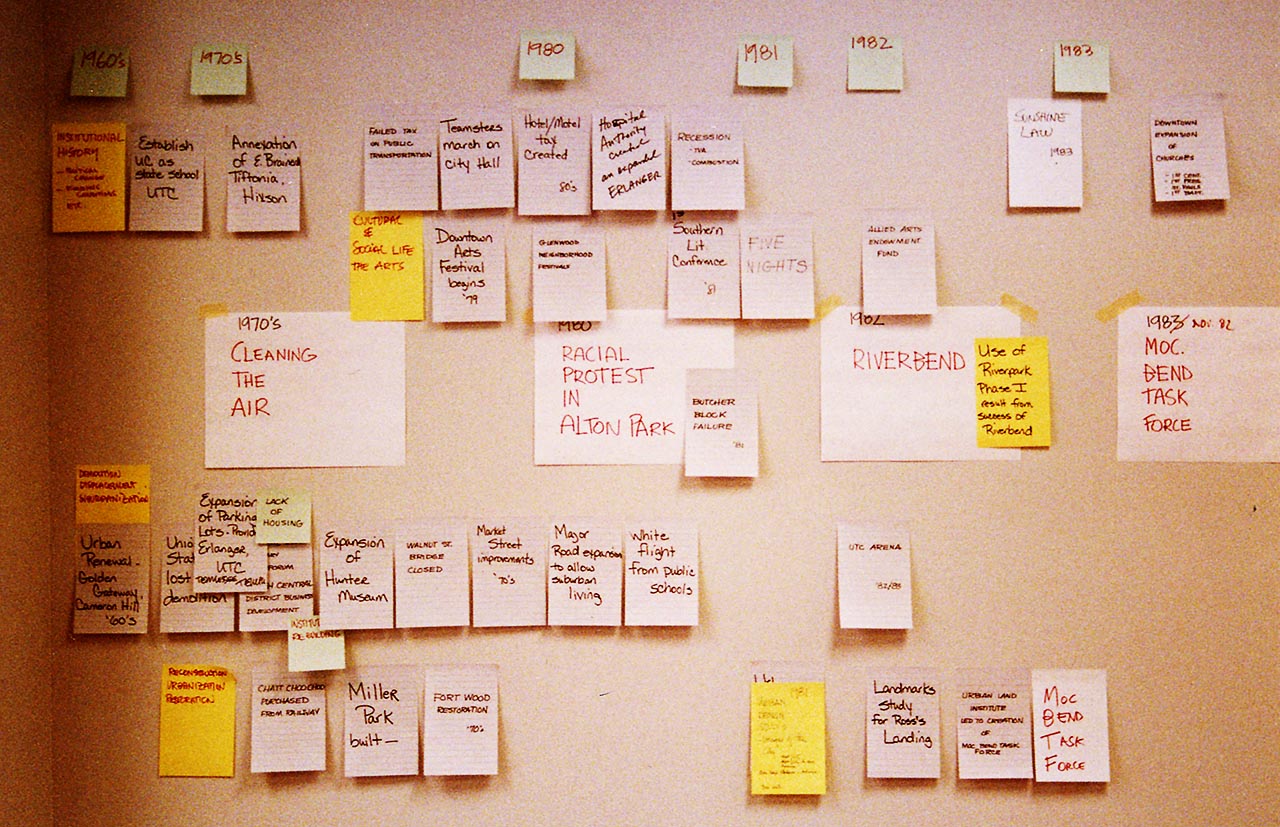

And interest multiplied when Venture announced its signature effort: a community-led planning process it called Vision 2000.

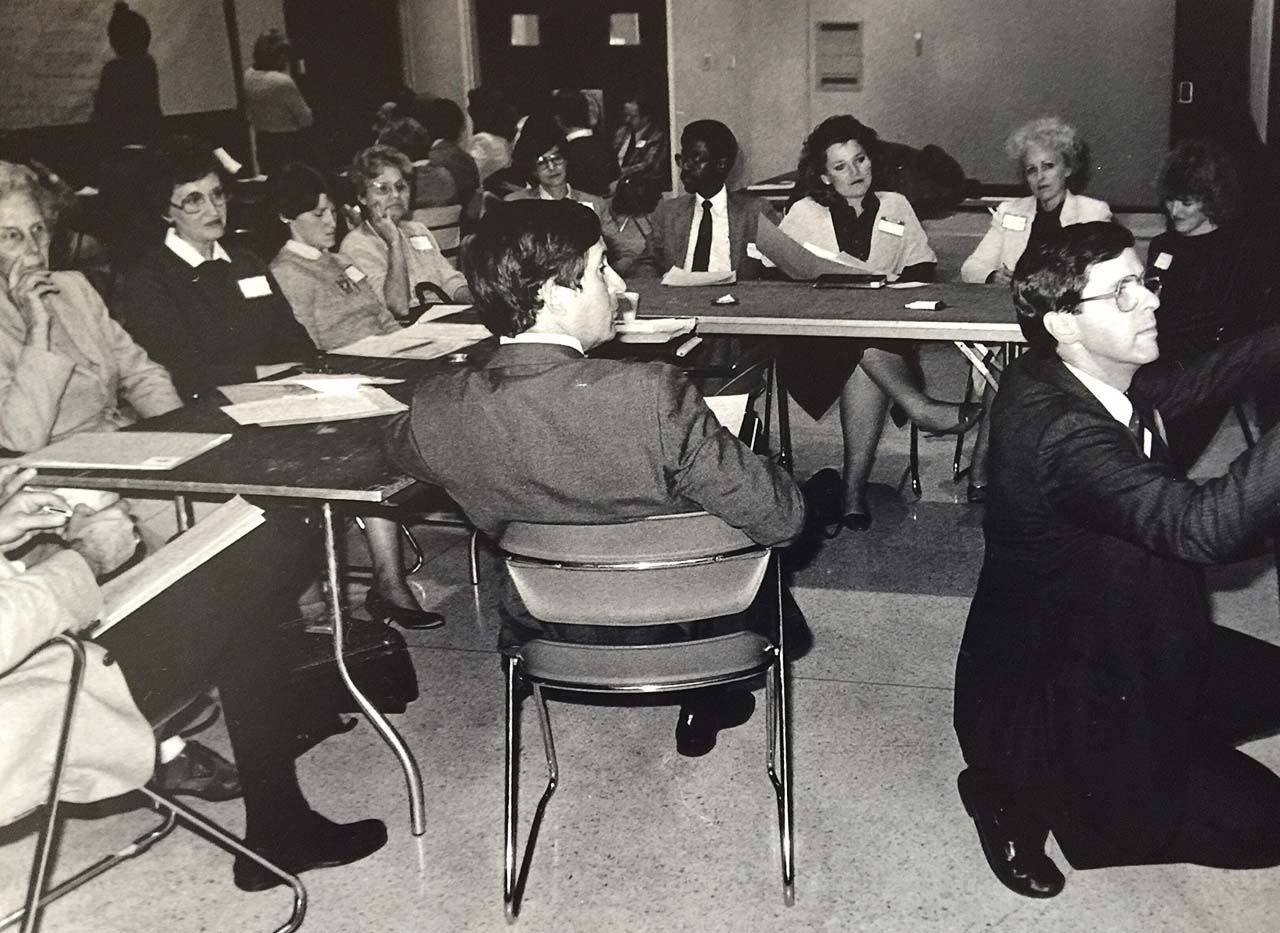

About 1,700 attended Vision 2000 sessions at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga’s student center designed to collect ideas” to improve “work, play, place, people, government and future alternatives,” Every opinion was counted, and no idea was considered too big or too small, trained facilitators told the groups that met to brainstorm the six topics. To ensure strong attendance, Chattanooga Venture, which was funded by the Chattanooga-based Lyndhurst Foundation, provided transportation and child care for those who needed it.

Many of the ideas were solutions to practical, street-level problems. A nurse, frustrated by the number of women she treated for abuse, suggested the city’s first battered women’s shelter. Other participants, frustrated by the lack of activities available for latchkey kids, suggested after-school programming. None existed at the time.

The list of needs grew and grew. What about a group home for troubled boys? A media campaign to end teenage pregnancy? A new county-city jail? An urban magnet school? A panel to address labor-management relations? A city council/mayoral form of government?

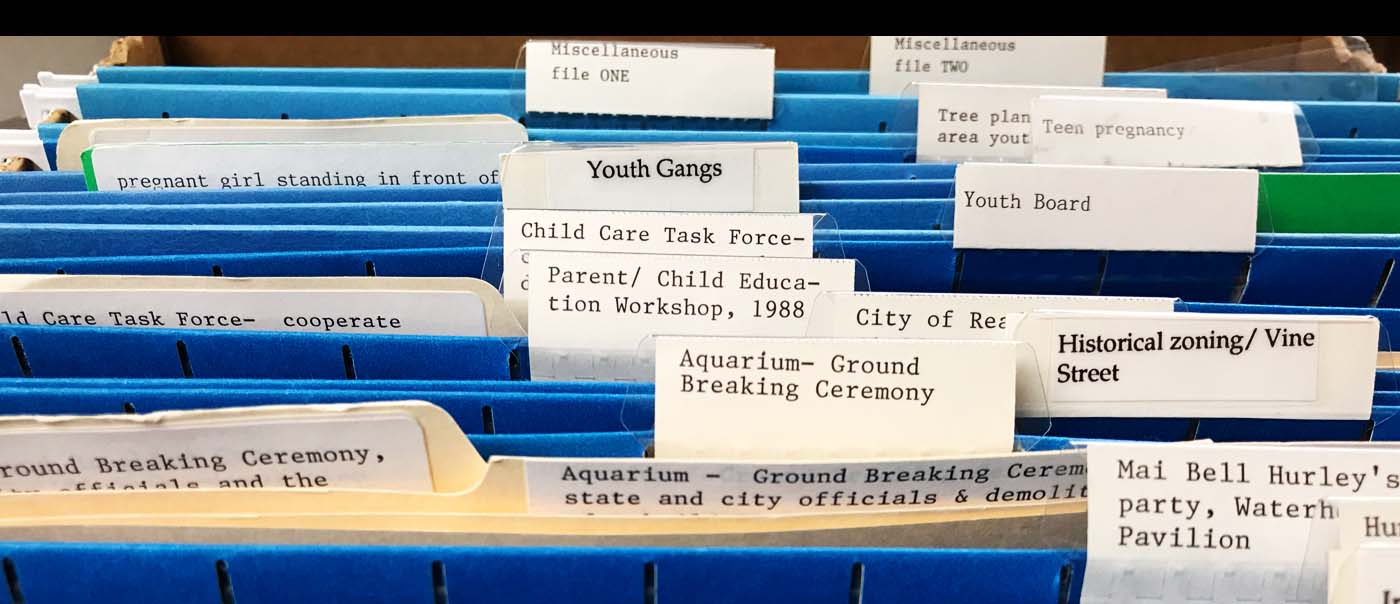

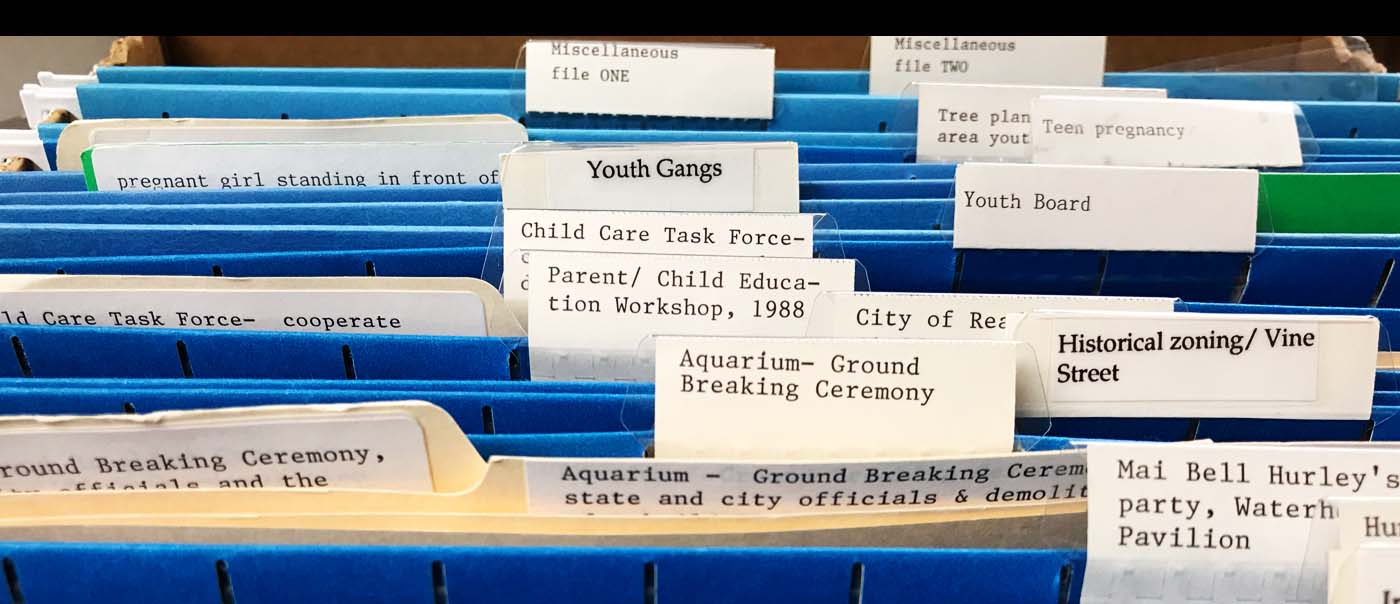

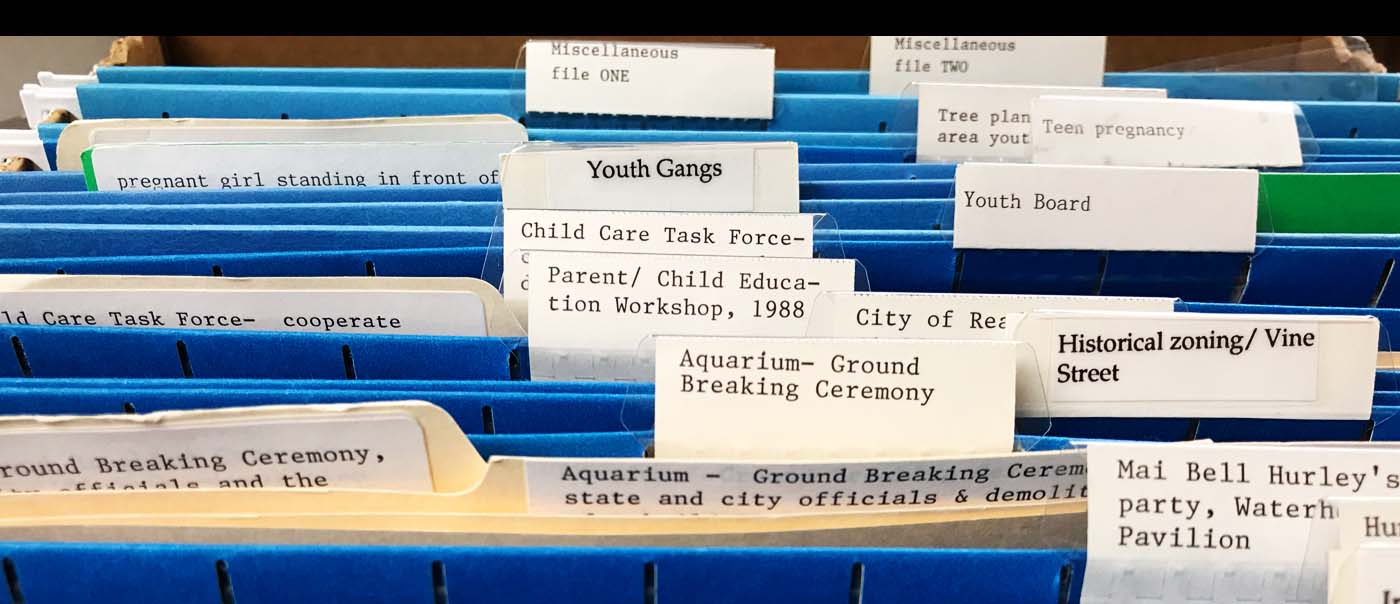

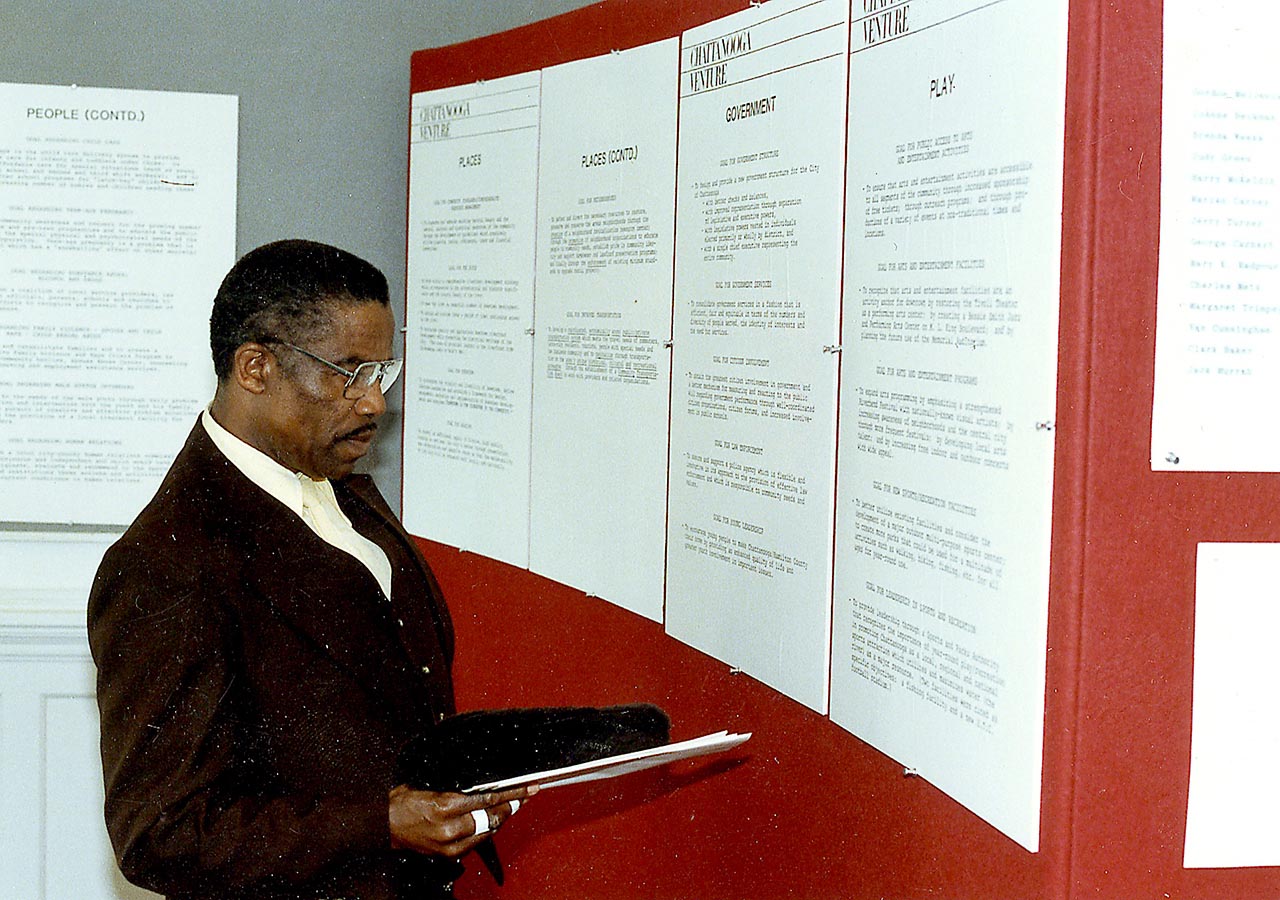

Then, after all community ideas were collected, the community was called together again to vote on the long list of 2,500 ideas. Six months later, the 40 community-determined priorities of Vision 2000 were handed off to Venture task forces that anyone with an interest could join.

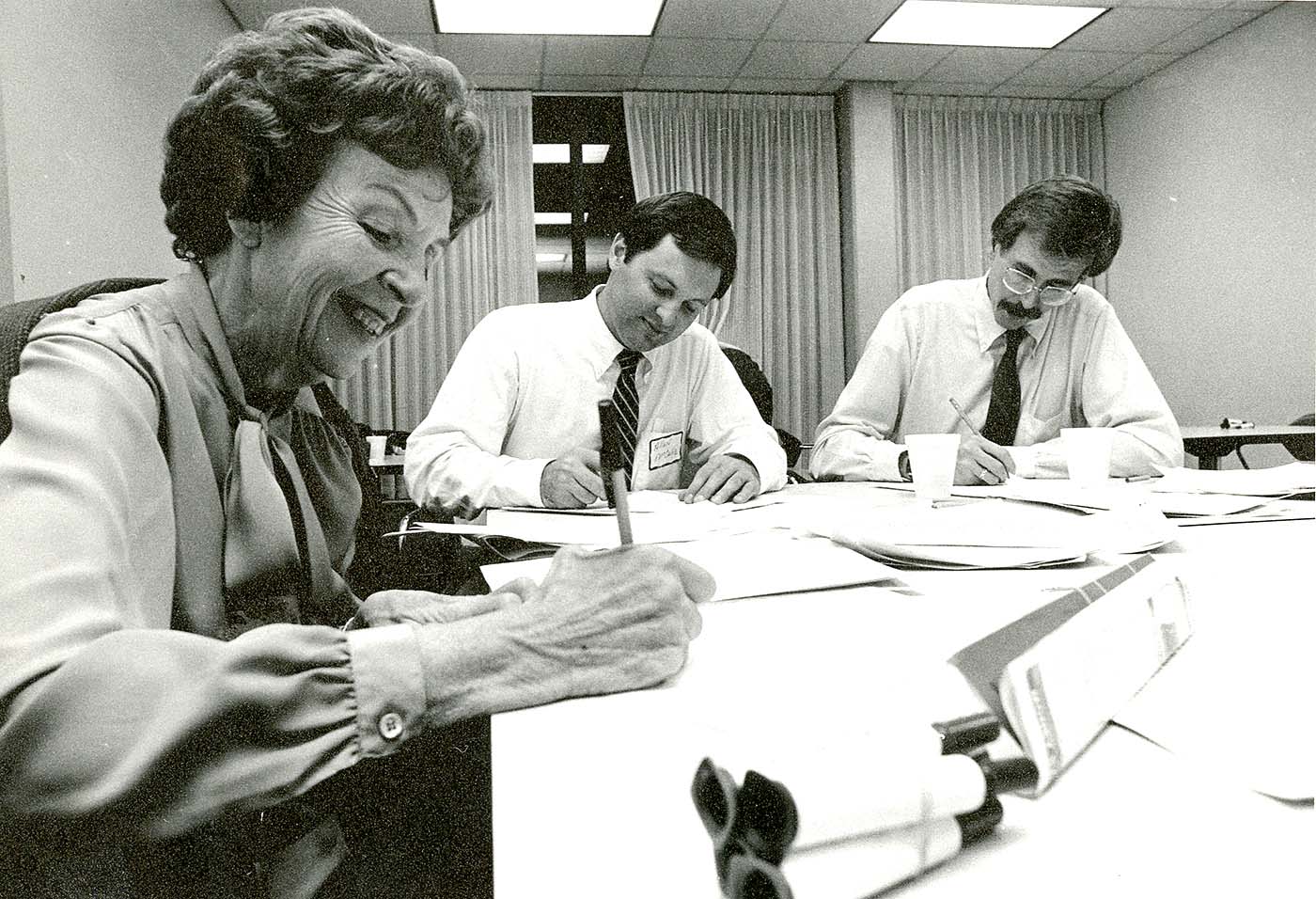

Citizens participate in Chattanooga Venture’s Vision 2000 community-planning process. During sessions on work, play, place people and government, participants were asked to write down and share their best ideas. /Chattanooga Public Library

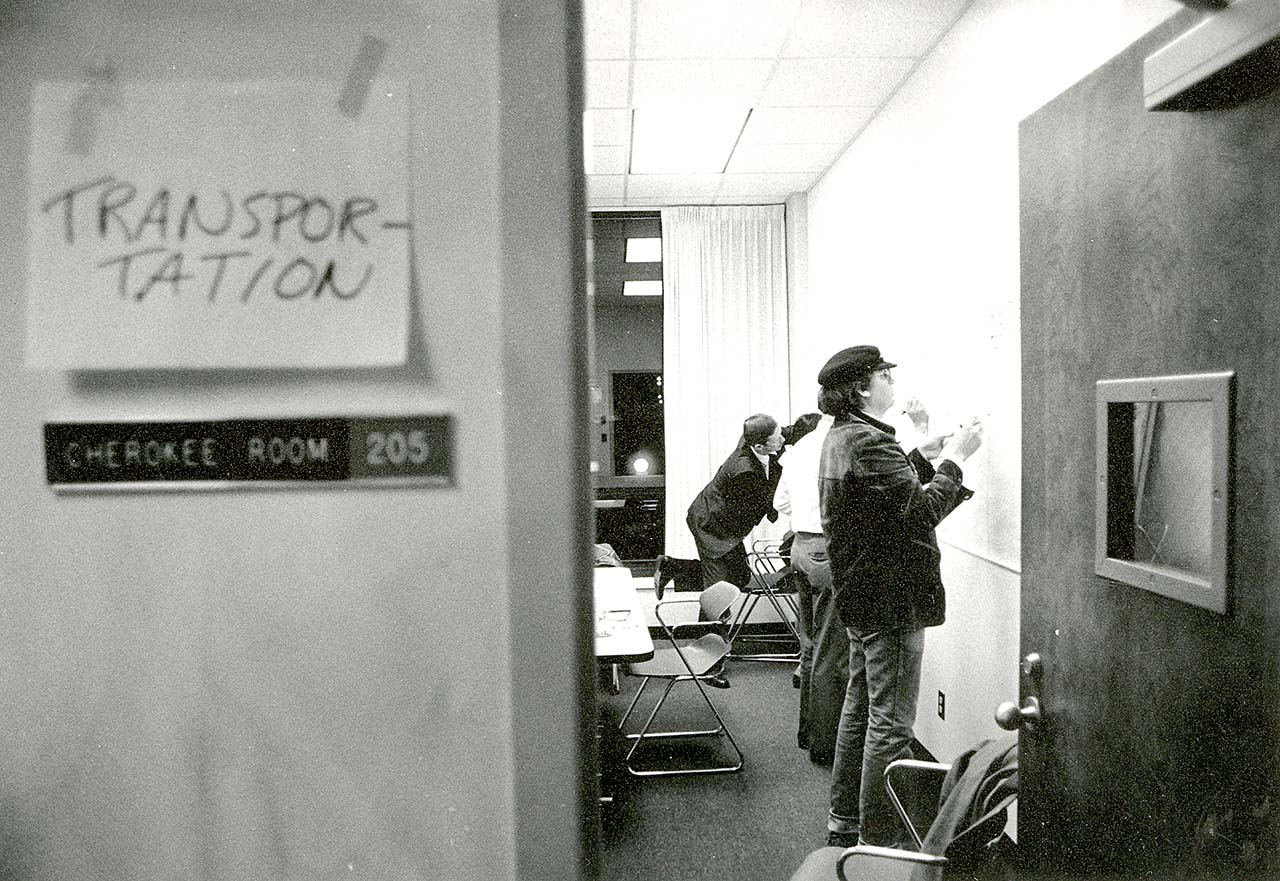

Facilitators, trained in nominal group technique, write down citizens’ ideas during Chattanooga Venture’s Vision 2000 community-based planning process, held at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga. /Chattanooga Public Library

Compelling scientific studies undergirded the approach, formally called “nominal group technique.” In the industrial era, paternalistic elites didn’t make decisions by committee, and they justified the closed culture by assuring themselves that they knew better. They had the money, the connections, and often the education that qualified them. Yet, study after study was showing that often their choices, made in a vacuum, were dead wrong. The wisdom of a crowd almost always trumped the wisdom of its smartest member.

Looking back from the perspective of the 21st century, the Tennessee Aquarium, and the surrounding development it spurred stands as the most tangible result of Venture, but a survey conducted in 1992 showed far more was accomplished. Over nearly a decade, 223 programs and projects reflected the 40 community goals determined through the Vision 2000 process, generating $790 million in investment.

Still, before anything tangible resulted from Venture’s Vision 2000, the very young nonprofit’s community planning experiment was drawing attention from across the country.

Nowhere, according to journalists and urban planners at the time, had such a process been attempted, and nowhere had an attempt at community engagement seen such widespread community buy-in.

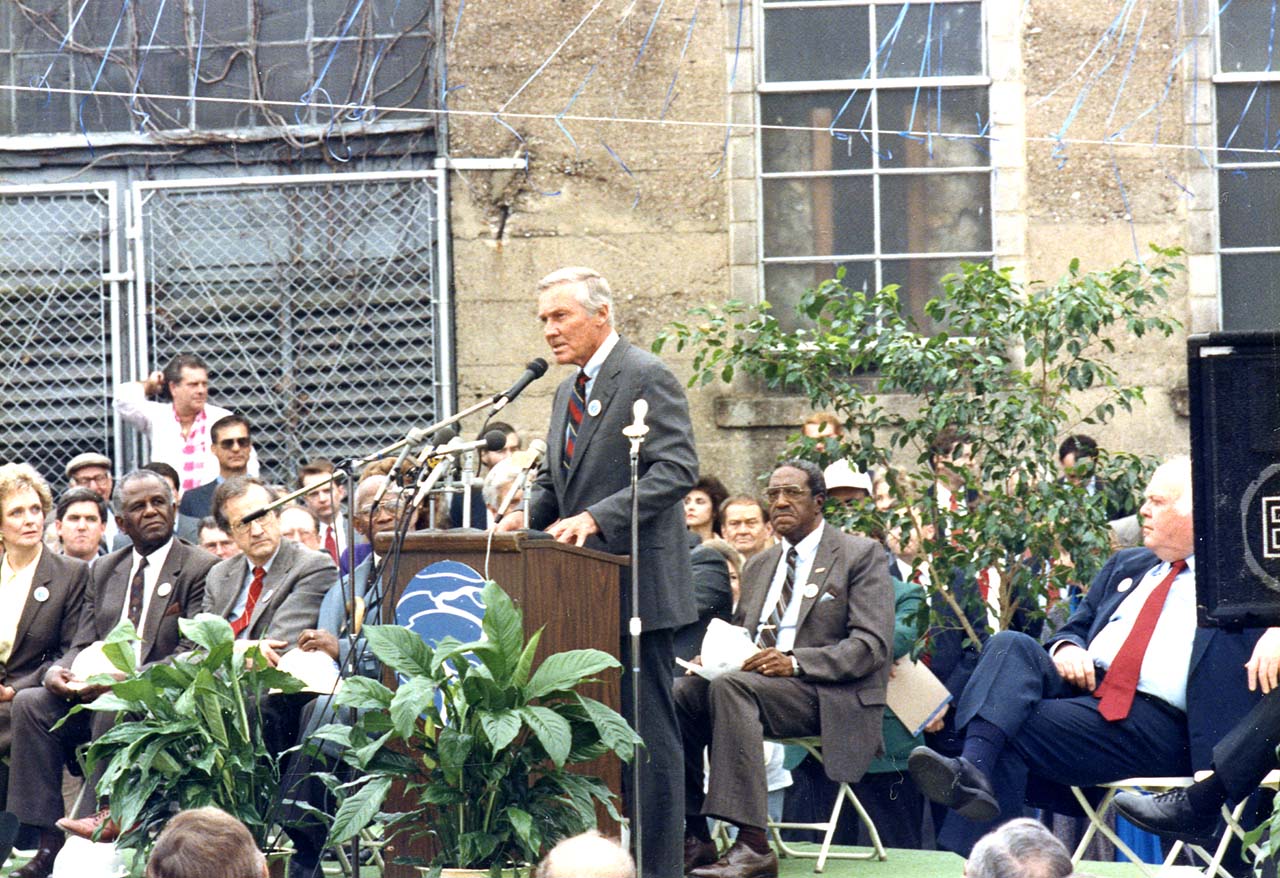

Momentum multiplied when James Rouse, arguably America’s most influential urban planner and developer, visited Chattanooga in November 1984, as Vision 2000 was underway, and crowned Venture the rising hope for fledgling cities across the country.

Rouse, who had made his fortune from the shopping malls and suburbs that grew out of the white flight that followed integration, had come to Chattanooga thanks to Rick Montague, the son-in-law of Coca-Cola bottling heir Jack Lupton who, at the time, headed Lyndhurst, the Lupton family foundation.

Over the years, Rouse had become passionate about the housing needs of the poor, and he told Montague, when they met at a conference, that he was looking for a city willing to partner, with his foundation, the Enterprise Foundation, to create a model for providing safe and affordable housing, as well as neighborhoods that celebrated economic and racial diversity.

Chattanooga could be an example to the entire nation, he believed. Venture was proving that.

“[I sense] a very impressive spirit here that something is going to happen in this city,” Rouse said on the stage of the Tivoli Theatre in the fall of 1984 before a crowd of more than 800 people.

His challenge would lead Venture to help create Chattanooga Neighborhood Enterprise, a nonprofit originally intended to build affordable housing, offer loans for home repairs and provide financial assistance for potential home owners.

Still, while Rouse’s visit validated Venture’s work, it also revealed a tension within the movement.

Many business leaders had reluctantly backed Venture only after Lupton had offered his support. They liked the attention the city was getting from the Vision 2000 process, but they remained more interested in solving the city’s image problems than transforming the way decisions were made.

How could they attract more tourists and new industry, they asked Rouse, who had once played a key role in revitalizing Baltimore’s downtown when he developed an aquarium and shopping district on the city’s riverfront.

Help Chattanoogans, listen to Chattanoogans, Rouse insisted when he visited Chattanooga in 1984, and the image problems will take care of themselves.

Once home, Rouse offered a more detailed response in a letter to Dan Frierson, then-vice president of the nonprofit Allied Arts.

In Baltimore, he and others had brushed aside the participation of the larger community, but times had changed, Rouse wrote. Political action required broad support. Plus, the community could offer strong leadership.

Nonprofits like Venture would pave the way to the future, he believed.

“Clearly,” he wrote. “(Venture) has mounted strong momentum which must be maintained and strengthened.”

Mai Bell Hurley, one of Venture’s architects and the nonprofit’s first board chairperson, agreed with Rouse. Chattanooga needed community leadership. After all, in her opinion, the powers that be had led the city nowhere thus far.

But Hurley, one of the most influential women in the city at the time, wasn’t a populist or an idealist, despite being so vocal about the need for bottom-up decision making. She was a pragmatist.

It was wonderful that so many had engaged in the Vision 2000 process, she wrote Lyndhurst Vice President Jack Murrah after the six-month process had ended.

“There is a blue sky, kid-in-a-candy-store quality” to Vision’s 40 goals, “which certainly is hopeful,” she wrote. “But (it) will only be helpful if reason and intelligence are brought to bear on its prospects.”

The revolution required dollars and cents, she believed, as well as a degree of savvy. So Hurley, the consummate fundraiser, began working the political channels that would bring resources to bear.

To grease the skids, Hurley, the city mayor and a handful of business and nonprofit leaders turned to then-Tennessee Gov. Lamar Alexander. Memphis had received millions in state dollars to redo its aging Orpheum Theatre and its iconic tourist district, Beale Street, and Chattanooga needed funding too, the delegates insisted.

The governor wanted to help, he assured Hurley, but Alexander had stipulations. He would only support bricks-and-mortar projects that were bold and unique. An example, he offered, might be a state aquarium on Chattanooga’s riverfront, an idea that had been proposed a few years earlier by University of Tennessee students and their mentor, architect Stroud Watson.

Once home, leaders of Venture debated how best to whittle down the 40 Vision 2000 goals to a short list of capital projects that might entice the governor. At first, it seemed Venture leaders would let the public decide.

Records show a Venture committee was working to develop a survey that would allow the public to convert the Vision 2000 goals into a list of capital projects. Alexander even wrote a cover letter in which he called Venture “the most important urban initiative in Tennessee” and asked for “advice on which goals are most important” and “what specific projects should be undertaken.”

Hurley quickly took over, however. Without seeking board approval, she began creating the list herself. Privately, she tested her ideas on those she respected or those with power who might stand opposed. Finally, she sought the approval of Lupton, as well as the city mayor and the governor’s staff.

“Timing now is everything,” Hurley wrote to Cooper, who was then on staff with Lyndhurst. “The tide seems to be turning in our direction … The advice we are getting from political experts is to keep a steady course … My real concern is that we not sponsor an opportunity to change the package.”

The decision backfired, however, when word of a finished “wish list,” as it became called, was leaked to the media.

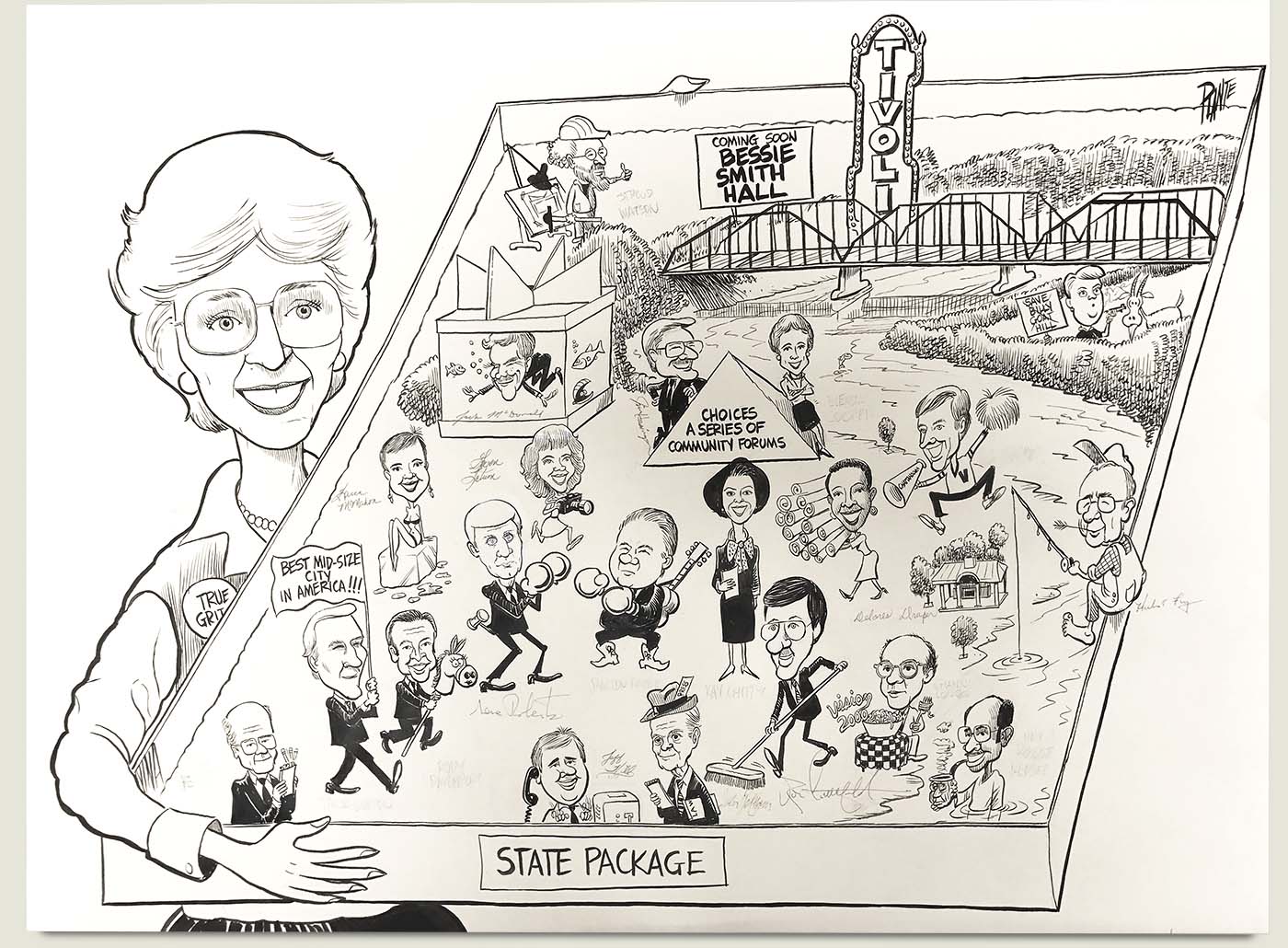

The “wish list,” shaped by the advice of business and political leaders, included funding requests for a river park and a fishing pier, both named by the public as priorities in the Moccasin Bend Task Force meetings. The Tivoli Theatre and Bessie Smith Hall, a performing arts center to be built on M.L. King Boulevard, were named.

But the “wish list” also included a state aquarium — which came as a surprise to some.

An aquarium had not been named as one of the 40 Vision 2000 goals, but, in a booklet, published after the community planning process had ended, an aquarium had been listed in a bullet point under the goal to “establish a comprehensive riverfront development plan.”

angry venture members passed out bumper stickers that read: “Return venture to the people!”

A “state ‘fish tank’ on the river” was listed, along with hundreds of other citizen ideas, during the Vision 2000 meetings.

Listing an aquarium would cement the governor’s support. That seemed clear to Hurley. And its inclusion had to be protected, she believed, because some thought funding for existing attractions such as the Tennessee Valley Railroad Museum and Memorial Auditorium should trump an aquarium.

“We need to stay united behind the package,” Hurley wrote Cooper. “It combines populist sentiment for the river and expert/professional advice about the best way to start the development!”

Leading up to the Venture board meeting, angry Venture members passed out bumper stickers that read: “Return Venture to the people!” and gathered at a city commission meeting to voice their opposition to the “wish list.”

“Venture is more than Mai Bell Hurley and Ron Littlefield,” a Venture board member said. “(They) don’t bring us into the process. (They) don’t get a consensus and then cut us off and go in here and talk to politicians … behind everyone’s backs.”

“I feel that we lost track of our primary purpose,” Pat Wilcox, a Chattanooga Times editorial writer and board member, told Hurley when the Venture board met. “The only people who were at the table were the people who had always been there.”

Others, including Montague and Littlefield, stood behind Hurley's “wish list.”

Cooper, troubled, pleaded with Hurley to hold public meetings that could educate confused or frustrated citizens about aquariums and the economic benefits they had brought to other cities, but Hurley didn’t want the aquarium to become a public debate.

Meanwhile, Hurley’s maneuvering paid off. Before the close of 1985, Alexander called with news. Chattanooga would be getting a windfall of $9 million, a funding pot that would radically shape the future of the renaissance already underway.

Few would ever know about Hurley’s role in shaping the state funding package because, to most, it seemed obvious that the puppet master, for better or worse, was Lupton.

After all, Lupton represented the deep pockets behind Lyndhurst, the Moccasin Bend Task Force and Venture. He also had been a generous donor to Alexander’s gubernatorial campaigns.

Venture’s Vision 2000 and its big talk about bringing bottom-up leadership to Chattanooga was all for show, some whispered, a theory still posited today. From the beginning, Lupton and his friends had wanted an aquarium and nothing else, some suspected. “Jack’s fish tank,” many opposed would call it.

In reality, Lupton, who didn’t attend a single Venture meeting and had remained relatively hands off, had originally opposed the idea of an aquarium.

At the time, there wasn’t a single aquarium in the U.S. losing money. So, for cities with access to a waterfront, an aquarium was a smart gamble. That was why the UT architectural students had pitched the idea in 1983. It was also why Steven Carr, the Cambridge-based planner hired by the Moccasin Bend Task Force, had worked an aquarium into the final plans for the Tennessee Riverpark.

Still, Lupton was unconvinced. He was especially cold on the idea of an aquarium that celebrated the local freshwater ecosystem, preferring instead something like a sportfishing center, letters show.

Eventually, it was Alexander who talked Lupton into backing and funding the aquarium that would become the catalyst to downtown development and tourism.

At the time, unbeknownst to most, it was Coke’s rival, Pepsi, not an aquarium, that Lupton obsessed over.

Pepsi, a sweeter alternative to Coke, was drawing customers with a modern marketing campaign that played into the culture wars raging in the 1980s.

Lupton, the country’s largest bottler, wanted Coke to go on the offensive in the soda fight, and he convinced reluctant Coca-Cola executives to go along with a new strategy.

Coke, like Chattanooga, needed to move into the new era, he believed, and like Lyndhurst it had to take big risks.

Soon, an advertising response was launched and, in secret, the Coke laboratories began work on a new, sweeter formula with a bit less bite.

Market research said the new formula was a home run. Only 10 percent of those who tested New Coke didn’t like it.

But New Coke, announced in April 1985, was an enormous flop and triggered an unprecedented brand backlash that is still studied by business school students to this day. New Coke was pulled, just 79 days after its launch, and Coke was relaunched as Coca-Cola Classic.

The whole debacle, which was unfolding as Vision 2000 wrapped up and Hurley was ironing out the state “wish list,” embarrassed Lupton, who, despite his distaste for the media, had served as a spokesman for the new product.

Soon, Montague would find Lupton sitting alone in a Tallan Building conference room, staring at a wall that displayed a map of all his Coke plants.

“It’s all gone,” he said, without emotion, his way of communicating the split decision to sell his company shares for $1.4 billion.

The 1986 sale, a move that shocked many, would further change the direction of the Chattanooga renaissance.

Suddenly, Lupton, armed with an enormous windfall, had attention to spare, which he turned to Montague, who by then was working on his next big idea for how to move Chattanooga forward.

The public had created a vision, but who would see it through? The answer, Montague found after much research, was incubating in St. Paul, Minn.

The Lowertown Redevelopment Corp. was a nonprofit seeking to revitalize an old warehouse district in St. Paul with a $10 million grant from a local foundation. With the money, the organization bought property and recruited developers to give the area new life, but its work was tempered.

Afraid their efforts might displace lower-income, working residents as redevelopment led to higher real estate prices and rents, the nonprofit’s leaders tried to set up checks and balances that would protect the district from the phenomenon of gentrification, then sweeping America. For example, the St. Paul group was radically transparent and managed by a diverse board.

Chattanooga needed an exact replica, Montague argued, a development engine that had the people’s trust and diverse interests in mind. “Greater Chattanooga Partnership Inc.,” as he called it, would be another major step in toppling the old order, which favored business interests above all, he believed.

Cooper, working alongside Montague at Lyndhurst, wholeheartedly agreed with the approach.

“Chattanooga has been plagued by a history — or at least by a pervasive attitude — that the city is sharply divided along class and race lines and that only certain ones on one side of that line get to make decisions,” Cooper wrote Montague. “In the long run, the citizens will have to pay (for) a large portion of these efforts through public funds and will be the users and consumers of the developments. Their attitude toward them and their involvement in them will continue to be crucial to their success.”

The stumbling block on this path, however, was Lupton.

For one, Lupton didn’t like the name Montague had settled on. RiverCity Co. was more fitting, he thought.

Montague named Jim Bowen, who had worked with him on the Moccasin Bend Task Force, to head the new development nonprofit, which would be seeded with $4.5 million from Lyndhurst. The task force, which predated Venture, had been the first Lyndhurst-backed effort at open and transparent public planning.

Lupton, meanwhile, had a different person in mind. Bill Sudderth, a developer who had worked with Lupton, had a background in real estate.

The transparency posed by Montague was another point of contention. Lupton didn’t want to do business in public, even if it was, in many ways, the public’s business. It was democratic enough that the board would be made up of various community and elected representatives, he thought.

“What haven’t we put, maybe the indigent or the lame? And the black member is being appointed by people that the community appointed. So they can’t look funny at us.”

- jack lupton

“You can’t do much better than we have tried to do as representation is concerned,” Lupton told a Chattanooga Times reporter in 1986. “What haven’t we put [on the board], maybe the indigent or the lame? And the black member is being appointed by people that the community appointed. So they can’t look funny at us.”

Lupton also had an opinion about who should be on the executive board of the new nonprofit, and Montague soon found he wasn’t on the list.

There was a part of Montague that understood why his father-in-law pushed him aside: He had never run a company. While he had many talents, no one considered him a businessman. Development was not his expertise.

Still, the move frustrated Montague. RiverCity, like so many other Lyndhurst initiatives, had been his brainchild, after all, and he had worked hard to lay the groundwork for it to be successful. But who was he to complain? It was Lupton’s money. It was Lupton’s foundation. It was Lupton’s show, Montague reasoned.

What’s more, Montague loved his quirky, unpredictable father-in-law.

Still, in the ensuing months and years, their relationship grew more tense. They disagreed about the look and focus of the aquarium, which Lupton by then was fully behind, having agreed to shoulder a third of the costs and even engage in public, verbal warfare over its necessity.

“We are going to build the Tennessee State Aquarium,” Lupton once wrote Ward Crutchfield, a state senator who had insulted Lupton in print. “And we’re not going to charge the taxpayers another red cent — and you know it! Now you take that message back to the boys who put you up to this crap!”

Montague and his father-in-law also continued to disagree about the type of leadership the city needed, as community engagement and goal-setting gave way to actual development. Montague was an insider, yet he couldn’t convince those spearheading the aquarium and RiverCity to see the benefits of transparency and public participation, he told Cooper in a letter a few years later.

“I felt psychologically hemmed in by JTL (Lupton),” Montague wrote.

Then, as RiverCity was buying up more than 30 acres downtown to later be sold and developed, Lupton made another surprising move.

“You have put in 10 good years for me,” he told Montague in the summer of 1987. It was time for a sabbatical.

Jack Murrah, a longtime Lyndhurst staff member and close friend of Montague, would assume Montague’s role at Lyndhurst, the newspapers announced, though Montague would remain on the board.

For years, Murrah, Cooper and Montague, who never rejoined the Lyndhurst staff after being put on sabbatical, tried to understand Lupton’s decision. Was it about ego? Control? The loss of Coke?

Lupton never offered an explanation.

As Montague’s role in the renaissance was changing, so was Venture’s.

RiverCity, which launched in 1986, began driving the city’s physical transformation, working hard to stir downtown development and manage the implementation of the Tennessee Riverwalk.

The aquarium, which wouldn’t open until 1992, was underway.

Chattanooga Neighborhood Enterprise, another child of Venture, also took center stage. It had opened with funding from Lyndhurst and real-estate mogul Bob Corker in 1986 with the bold aim of making housing for the very poor fit and livable within a decade, according to records. Ironically, CNE ended up working more and more with RiverCity to develop market-rate housing that would draw the middle class to Chattanooga.

Venture’s place in the community, however, became cloudier.

Hurley remained as Venture board chairwoman, while also serving on the board of Lyndhurst and RiverCity, but Littlefield, the nonprofit’s first executive director, left in 1986 to run for public office. He would go on to be elected to two terms as the city's mayor.

To replace Littlefield, Jim Hassinger, who had been working at the planning commission, was hired to run Venture, then a few years old and still solely funded by Lyndhurst.

Under Hassinger, Venture hosted a series of community forums on “policy choices facing the city,” but Venture’s main focus turned to public relations. A changing Chattanooga was gaining more and more notice outside the city. Scholars, hoping to find a model that could be passed on to other troubled post-industrial cities, even gave Venture’s experiments a name: “The Chattanooga process.”

As interest grew, some group had to step into the marketing and promotions role, Hassinger argued. Also, with the conclusion of the Vision 2000 planning process and the controversy surrounding the state “wish list,” local trust and interest had begun to wane. So Venture also needed a campaign aimed at Chattanoogans.

In agreement, at first, Murrah and the Lyndhurst board funded the development of an extensive marketing plan.

RiverCity, Lyndhurst and the Chamber of Commerce would play a role in promotion, but Venture should serve as ground zero, the 1988 report argued, because it connected with the people and played the largest role in sparking the turnaround. Still, Venture would never own the rights to the story.

“Hold everything!” Lupton wrote after reading the consultant’s report.

“We are focusing on the messenger and not on the message,” Hurley wrote the consultants, after hearing their strategy. “What is the message? And who will say what it will be?”

Behind the scenes, letters show Hurley worked to derail the marketing plan, which positioned Venture as the lead communicator. Her interest in Venture was giving way to new commitments. RiverCity, she and Lupton agreed, should be the promoters of downtown, as well as the teller of Chattanooga’s story.

Meanwhile, an ideological divide between the renaissance architects became more and more apparent.

Hurley, once Venture’s loudest advocate, was beginning to think the citizen-led nonprofit no longer had a role to play. Less than a year after the marketing plan was debated, she left the organization she had given birth to and became the first woman elected to the Chattanooga City Council, formed after a federal judge ruled the city’s longstanding commission-style government violated the constitutional rights of black residents.

Venture board members believed the organization should be working harder to connect with and empower Chattanoogans and avoid any semblance of elitism. After all, Venture had launched to improve the community by engaging all citizens in local decision-making.

Hurley, however, had had an epiphany, she wrote Montague in 1989.

Venture had always been elitist, she argued, and that was its virtue.

“It was designed … for those that want to be hopeful and helpful, for those who want to do something for others, who want progress and change, who are tolerant, who have taste, who believe that this community is capable of being better than it is,” she typed to Montague. And it should resist the “average aspirations of the average Hamiltonian.”

If Venture wasn’t willing to be unpopular, she wrote, then there was no reason for it to continue.

Montague, saddened by her new thinking, disagreed.

Chattanooga desperately needed the peacemaking and consensus building that Venture had once embodied.

“If leadership forces cannot adopt listening as the primary element within leadership,” Montague replied. “then all will be vanity and all will be arrogance and our glorious project will become tombstones!”

“If leadership forces cannot adopt listening as the primary element within leadership, then all will be vanity and all will be arrogance and our glorious project will become tombstones!”

- rick montague

Hassinger, Venture’s director, would leave Venture not long after Hurley.

So Montague, determined to return Venture to its roots as a catalyst, convener and consensus builder, stepped in as Venture board chairman for a short time. He turned to Cooper, still on staff with Lyndhurst, for help.

Many, including Hurley, it seemed, had forgotten the nonprofit’s back story and mission.

“The stories, the emerging plans and the context must be repeated again, and again, and again,” Montague wrote Cooper. “Until some group fills this need, the heady days of the earlier ’80s won’t return, and the renewal we seek will not take place. … Before people can feel they belong, they must first understand.”

Quickly, Cooper, who left Lyndhurst in the fall of 1990 to head Venture, worked to right the ship.

She asked Murrah, then president of Lyndhurst, to increase its funding, justifying the request by outlining a slew of new activities for the organization that would help it reconnect with Chattanoogans.

Under Cooper’s leadership, Venture opened a “facilitators bank,” which offered trained individuals who could help burgeoning community groups with planning and conflict resolution. In addition, consultants were hired to help neighborhoods organize and identify their hyper-local concerns. Venture also published materials and organized community meetings to educate locals on the new form of city government. A separate project involved Venture in helping public housing residents learn to self manage the government-subsidized property they shared.

But her boldest idea was not a new one: The city needed to come together again and engage in the visioning process that had put Chattanooga on the map.

In the early 90s, Venture was inundated with calls from journalists, urban planners, civic activists and political leaders, all wanting to know how “the Chattanooga Process” could be used. And if the model, pioneered in Chattanooga, was giving hope to the rest of the county, why couldn’t it still serve the city that birthed it, Cooper thought.

The redux would be called Re-Vision 2000, but this time, Cooper was determined to learn from the past. In the first community visioning exercise, nearly a decade earlier, crowds had been far too white, middle class and middle aged, she believed. This vision would include far more diversity, and touch on what might have been missed by Vision 2000.

At first, Murrah was thrilled by the energy Cooper injected into Venture.

“Eleanor has taken Venture by storm,” he wrote to the Lyndhurst board. “Everything is changed or changing … the agenda is bulging with new undertakings, both substantive and celebratory.”

Funding, however, was becoming a bit of a quandary, he acknowledged to the board.

Cooper wanted Lyndhurst to up its support, which sat at $400,000 in 1991, by 50 percent, and Murrah told the board he thought Lyndhurst should be generous with Cooper in her first year as head of Venture. Still, he wrote, Lyndhurst couldn’t sustain that level of funding for Venture in future years. The foundation also was committed to being the principal funder of CNE, RiverCity and the Tennessee Aquarium, among other things. Venture was important to the community, he argued, but it needed to begin fundraising outside of Lyndhurst as well. A diverse pool of funders would best ensure its longevity.

Surprised but not dejected, Cooper accepted the challenge, but the reception of business and political leaders she approached for financial support was chilly.

“Venture — a bunch of rich people — just concerned with poor/social issues,” she wrote on a notepad, transcribing the thoughts of some city council members.

“We don’t need any new ideas,” she jotted down, after another meeting, during which she had asked for support of Re-Vision 2000.

The “economic power structure” just couldn’t see how Venture was helpful, someone else explained to Cooper. The nonprofit “had outlived its usefulness.”

Then, a bigger challenge emerged.

Lupton was leaving Lyndhurst, he announced unexpectedly in October of 1991, and his children, most of whom lived outside of Chattanooga, would be taking over. It soon became clear that they wanted to take the family foundation in new directions.

At the first meetings of Lyndhurst’s newly configured board, Murrah argued Venture’s worth, while also acknowledging that Lyndhurst should reduce its funding and force Venture to be more financially independent. Still, the new board voted to stop funding altogether. CNE was addressing the downtown housing deficit. RiverCity was overseeing the completion of the aquarium and the riverwalk and promoting economic development downtown. How was Venture still needed, they wondered.

After the vote in 1992, Murrah would deliver sobering news to Cooper. Lyndhurst would be severing ties with Venture, Murrah wrote, and would offer one final grant of $1 million, the equivalent of two years’ funding, to see it through the transition.

How could the “essential ingredients of civic progress be made available without the exceptional and inevitably temporary support of a single foundation?” Murrah asked Cooper in the same letter.

“It is, perhaps, a great irony that the best time to force the resolution of that issue … is when Venture is at the peak of its performance.”

As Lyndhurst pulled away from Venture, the future of the near-decade-old nonprofit seemed uncertain.

Without the protection of Lupton and Hurley, it seemed no political and business leaders were willing to fund the organization. The city’s image problems were beginning to fade away. Chattanooga was back on the map and long-awaited development was underway, filling downtown with bodies and businesses.

Meanwhile, in early 1993, Re-Vision 2000, Venture’s second community-led visioning process, was underway, and the 2,600 participants, from 40 Hamilton County zip codes, were sending another message to Cooper. There was more work to be done.

And this new communitywide vision, Cooper believed, better reflected the city’s diverse population and perspectives. Thirty percent of participants were under 25. Twelve percent were black. Twenty-four percent came from households earning less than $20,000 a year. And 85 percent had not participated in Vision 2000.

“I felt valued,” said Sajeena Geevarghese, a teenage Re-Vision 2000 participant who was interviewed for a short video about Venture. “Someone is finally listening.”

“The least one sometimes can come up with the best idea,” said Alberta Bayne, a black woman who bounced a baby on her knee during one of Re-Vision meetings. “We may be common-thinking people, but we all are created equal.”

“The more voices that converge, the more they (leaders) have to listen,” said James Fouther, then the pastor of Chattanooga United Church.

“Things can change,” said Alva Crowe, an American Indian resident. “Things can happen when people come together and work together.”

“We made a strong leap forward, we walked on the moon, so to speak” added then-Hamilton County Executive Dalton Roberts, referring to the first community visioning process. “So are we going to close down all our rockets now, or are we going to look at other planets? We certainly have not arrived. There are a lot of things we need to do.”

Still, the success of Re-Vision 2000 and the chorus of voices it ignited failed to motivate financial support for Venture.

So, in a last ditch effort, Cooper called Lupton. He alone could save it. She knew that much.

He was behind her, he told her when she reached out, and he agreed to gather a powerful group to brainstorm Venture’s future.

On June 30, 1993 some of the city’s most influential players responded to his call. Around a table at Venture’s headquarters on Broad Street sat Hurley, Roberts, Corker, photography business magnate Olan Mills and Chattanooga Times owner Ruth Holmberg. Accounting executive Joe Decosimo and developer brothers Bo and Bill Sudderth and Jim Catanzaro, who had been recently elected chairman of Venture, also came.

At first, the group debated whether it made sense for another organization, like RiverCity, to absorb Venture, but no conclusion was reached. They also debated Venture’s role in the community until Lupton broke in.

“I want to hear from Ele [Eleanor],” he said.

Nervous, Cooper offered up the solution she thought would work best. Venture could divide into two units. One would continue to work with the community and incubate new ideas. The other would promote “the Chattanooga process.” With interest so high, it could serve as a source of revenue, she argued.

But midpitch, Lupton abruptly cut Cooper off.

He had changed his mind, he told the room.

Some in the group snickered. Lupton so often suffered from a sudden change of heart.

“Does anyone want to make the argument for why Venture should die?” he asked the room.

Hurley lifted her hand.

“I’ll take a stab at it,” she said.

A few weeks later Cooper found herself in the nightmare, hanging from the banister, alone.

After the meeting Lupton would offer an olive branch: $100,000.

But Venture was already dead. Cooper could feel it.

The end, detailed in her journal, would be messy. Hoping to make what was left of Venture’s funding last, Chairman Catanzaro came up with a plan to fire almost the entire staff without consulting Cooper, who was out of the country on vacation. She was told to execute the plan upon her return.

Shortly after, in the fall of 1993, Cooper, frustrated with the board’s treatment of her and their failure to aid in fundraising, penned her resignation. When Lupton heard the news, he also wrote Catanzaro. It was time, he said, to let Venture fade away.

“I … am saddened by the ending of a vision that we shared and the rupture of an organization that once served the community,” Cooper wrote Murrah, in the aftermath. “One lesson that is learned is that history does not last long.”

Montague, always the optimist, tried to console her.

“We may have lost some small wars; we may have tried to please some corrupt, stupid, insane, inept and conspiratorial ‘generals’ in the war,” Montague wrote to Cooper. “We did what we could.”

They were idealistic, fed up with “the same old B.S., racism, class conflict and middlebrowism.” They had wanted to trust and listen, to give power and voice to everyday people who felt alienated and angry, he wrote. Later, though, they found they were alone in those hopes, and it hurt.

“Some key actors weren’t in the fight for the long haul, but, in truth, I don’t think they saw a long haul,” Montague wrote.

Still, it was a great ride, he added, and “the world changed a little bit - in some rather fundamental ways.”

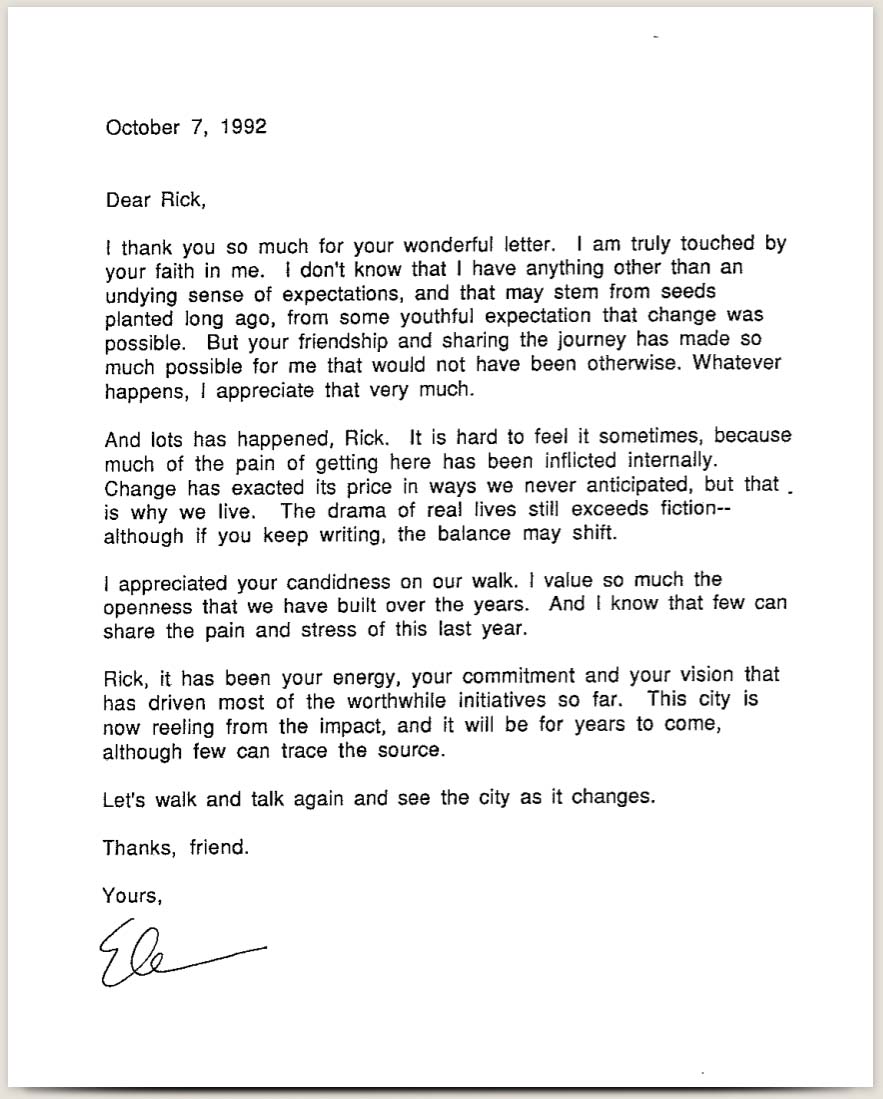

A few weeks later, Murrah and Cooper met and tried to make sense of a decade as they hiked along a trail at the foot of Lookout Mountain.

Afterward, Murrah jotted Cooper a note.

“I have no more points to make about Venture,” he wrote. “What happened was that good people did the best they could with what they had every step of the way. Also some bad people did the best they could. Some died. Not enough.”

“And thus was the fall of the house of Usher.”

In the spring of 1994, Murrah received a copy of Venture’s last grant report.

It detailed how Re-Vision 2000 had created a task force to carry out more than two dozen of the most important plans to emerge from the city’s new vision.

An update on the neighborhood networks detailed how Venture would continue to help neighborhoods organize. Under Cooper’s leadership, neighborhood associations had grown from six to nearly 80.

Cooper had resigned and the shell left of Venture had moved to Chattanooga State Technical Community College. A few years later, it would disappear completely. But the report described how Venture was emerging from a difficult transition and was committed to seeing the new vision through.

Murrah, knowing that wasn’t the case, scribbled a note on a yellow sticky pad and stuck it on top of the report before he sent it to be filed.

“Mark this as the final report from Venture. Close the books. Burn the files.”