t was the last

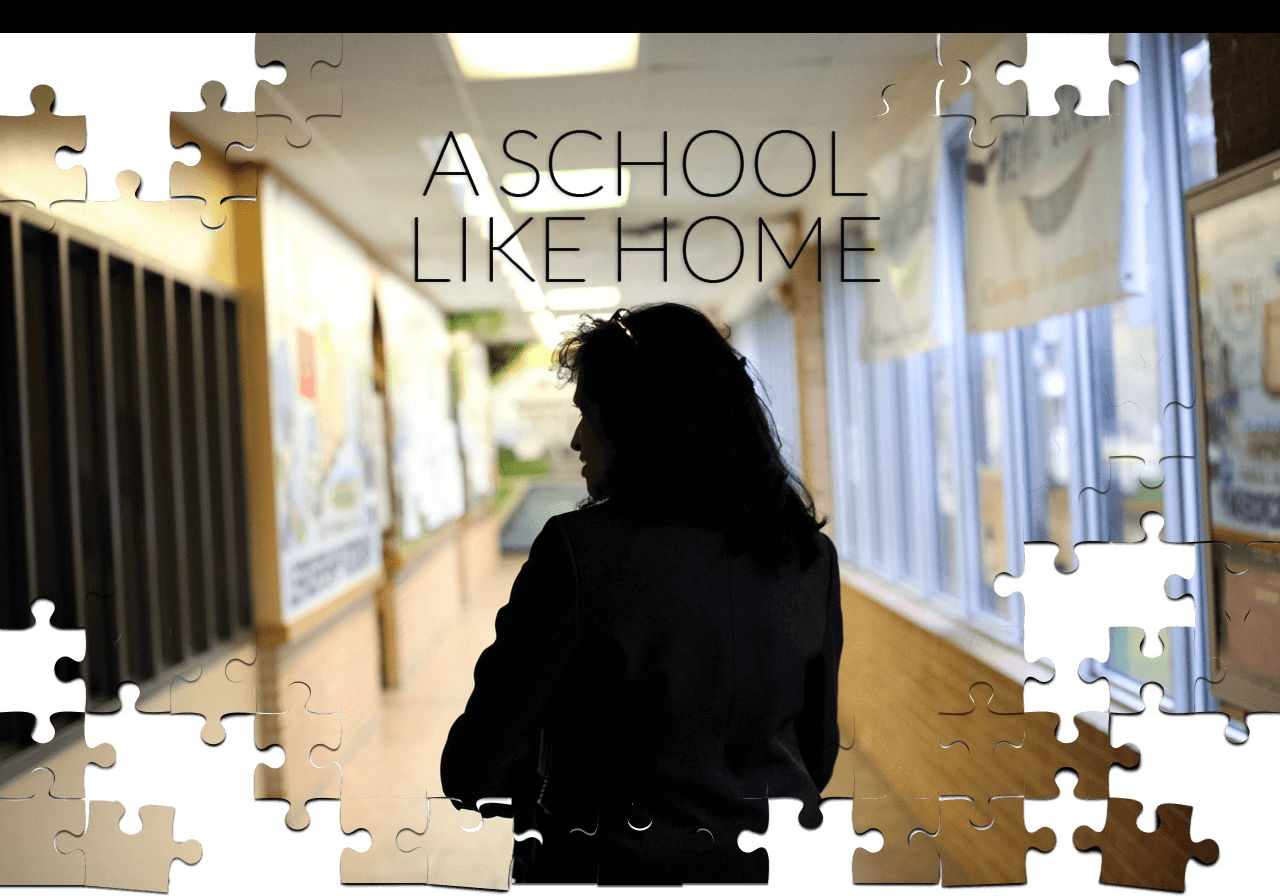

day of still hallways and strategizing, the last chance for Elaine Swafford, the executive director of Chattanooga Girls Leadership Academy, to prepare her team of educators, who were mostly green and mostly middle class, for the task at hand.

t was the last

day of still hallways and strategizing, the last chance for Elaine Swafford, the executive director of Chattanooga Girls Leadership Academy, to prepare her team of educators, who were mostly green and mostly middle class, for the task at hand.

After a week of training, some teachers were already exhausted. A pair fretted as they boarded an elevator, whispering concern about the year’s goals.

But Swafford didn’t notice.

“Let’s go,” she said, bursting through double doors and rushing past with a two-way radio in hand.

The bus was waiting, and she needed everyone to move along. Now.

Some teachers asked where they were going.

“It’s all about cultural competency,” Swafford said, walking briskly past them in a navy pantsuit.

“This is about getting to know where our kids come from,” she added after boarding the bus.

Three miles later, the bus parked on the curb of the College Hill Courts housing project in Chattanooga’s Westside neighborhood, a remnant of a Depression-era federal housing program intended to temporarily accommodate the poor.

“Let’s go,” she shouted, fliers in hand.

“What do we do?” one teacher asked another. “Where should we go?”

Swafford, a 56-year-old education veteran, left them behind, cutting through alleyways toward people perched on porches.

“We are here from Chattanooga Girls Leadership Academy,” she said as she approached.

“We just want to visit with our students and remind everyone that school is starting back,” she added before being interrupted by a tall, muscular girl, who bounded around a corner.

Former CGLA student Kenyetta Brown sits on a picnic table next to her family’s new apartment complex with her friend Brenton Adams in November. Kenyetta’s family moved to this complex in September, and she now attends Ooltewah High School.

“Dr. Swafford,” the girl called out, embracing the school leader, who remained composed.

Swafford knew Kenyetta Brown, a sophomore at CGLA, and her story. Still, the 15-year-old used the moment for a testimonial.

She lost her father the year before and had wanted to give up on school, she reminded Swafford. But teachers convinced her to stick it out and take a stab at leadership roles and writing. Her report cards included A’s now, and she even had a poem published in a national collection of high school writing, she told Swafford.

“The teachers helped,” she said. “But I did it,” she added with a big grin.

“Well, get ready,” Swafford told her, knowing the rigors that lay ahead at the almost all-poor, all-minority girls charter school in Highland Park.

The message: Good progress, Kenyetta, but not good enough.

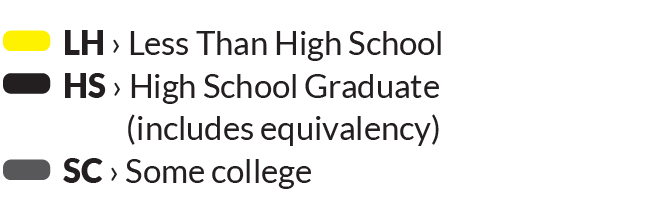

ince the Great

Recession the local public school student body has dramatically changed and not for the better.

ince the Great

Recession the local public school student body has dramatically changed and not for the better.

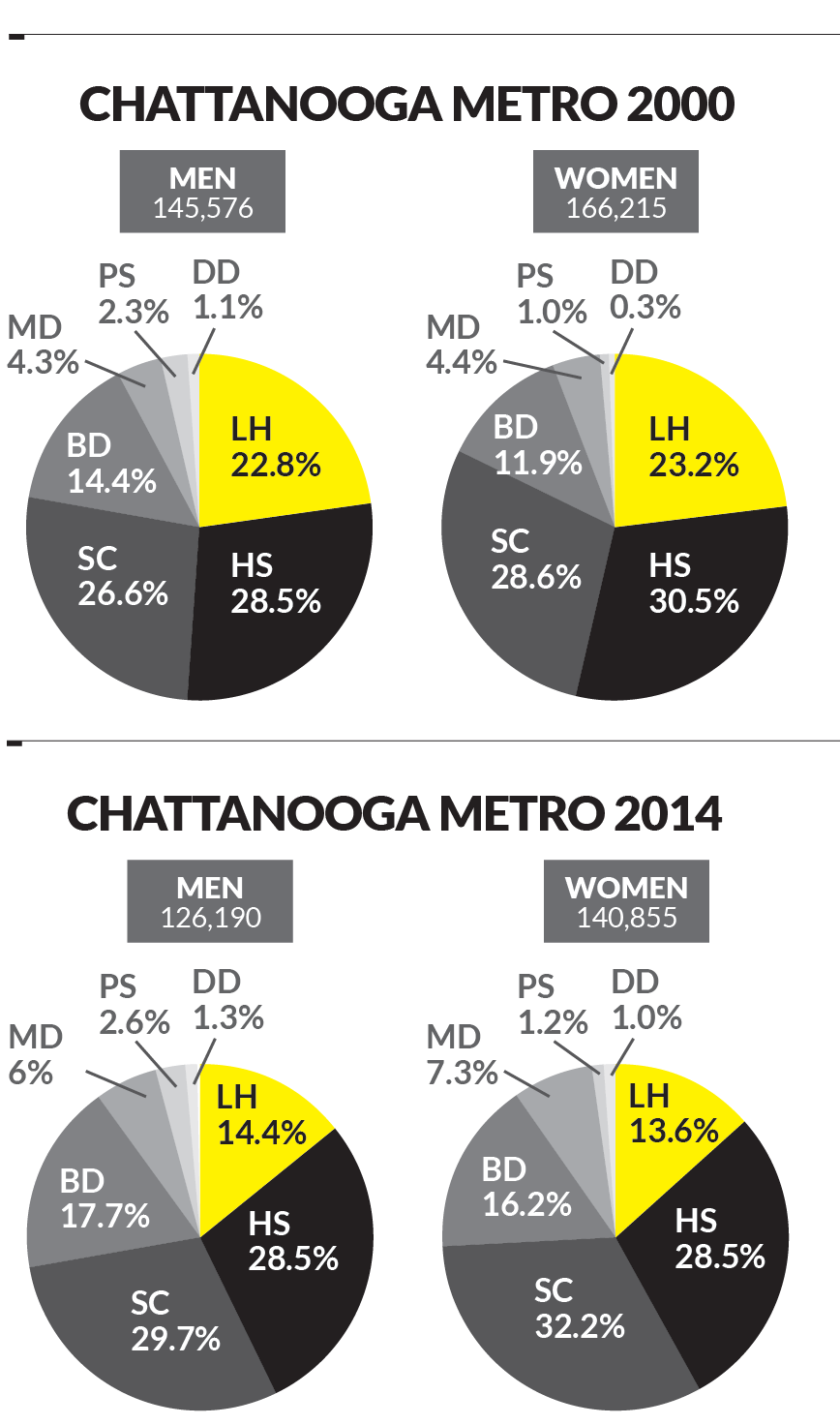

Thanks to a growing birth rate among poor women and the increased number of financially unstable households throughout the Hamilton County, the ranks of poor children in the Hamilton County school system has swollen at a stunning rate.

While the overall school population has grown just 12 percent since 2007, the number of economically disadvantaged children counted by the Hamilton County school system is up 27 percent, and now, for the first time in history, the county is educating more disadvantaged children — over 60 percent— than not.

The county was already playing academic catch up with the state and other districts, and these enrollment shifts aren’t helping school leaders move the needle, local educators say. Only 35 percent of students have been leaving local schools with the ability to compete for jobs that pay a living wage. So, for progress to occur, public schools not only have to bring delayed students up to basic comprehension but also push them up to the achievement levels of their more advantaged peers.

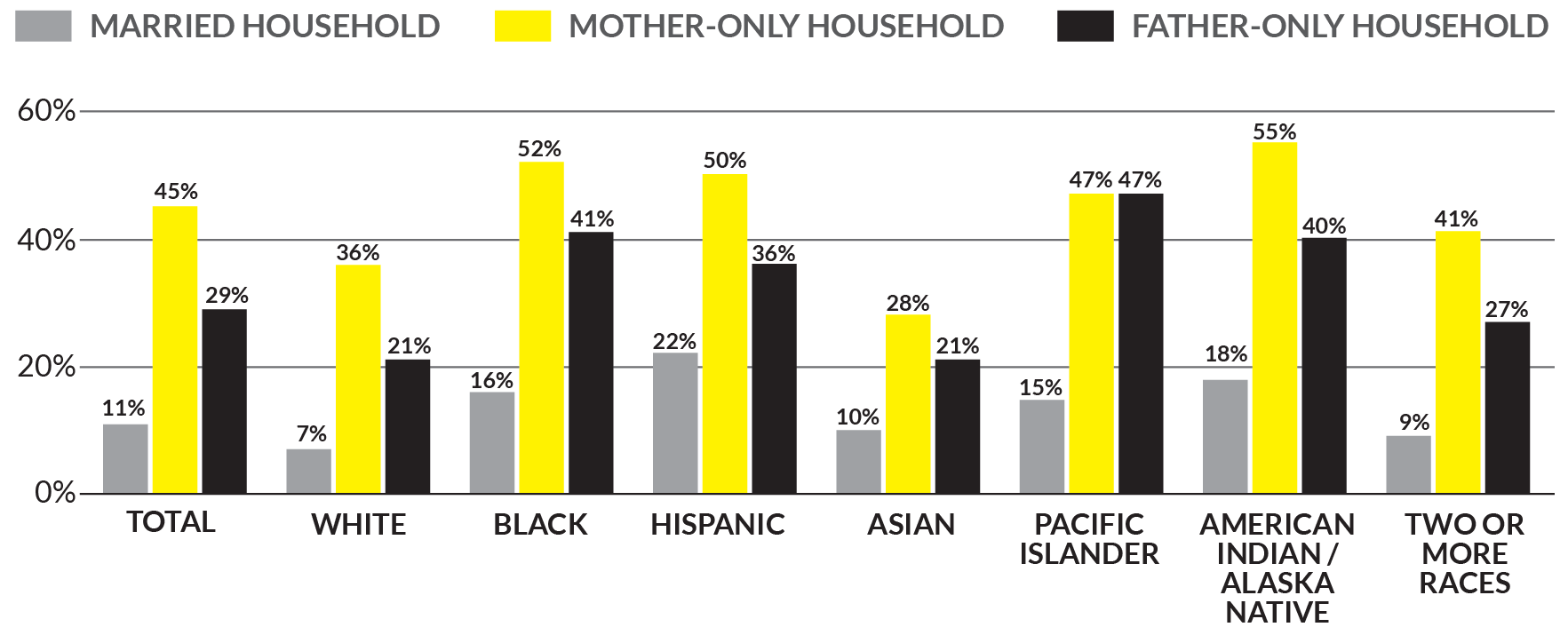

A significant share of the poor children entering public schools are being raised by strained and stressed single mothers who grew up in poverty but are trying to make ends meet with low-wage work, little education and little help, data show. Their early exposure to isolated and concentrated poverty often has a toxic effect, research shows, and puts them far behind in basic literacy, the most important building block for their education.

And addressing these deficits remains a daunting task, experts admit.

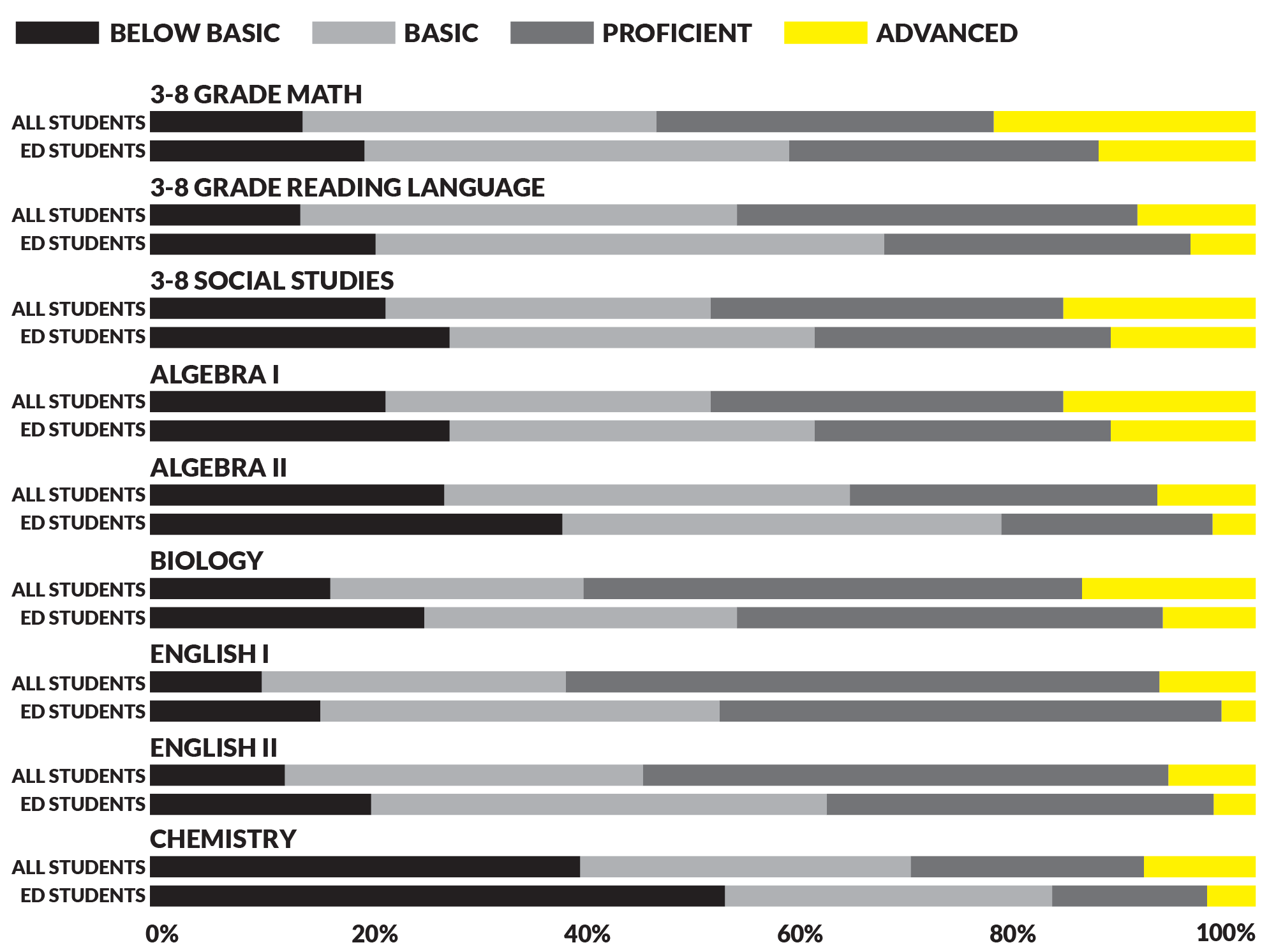

Source: Hamilton County Department of Education

Decades ago, in the early years of education reform, many, like Washington, D.C., schools disruptor Michelle Rhee, criticized public schools for using poverty as an excuse for low-classroom standards. But recent research has challenged that thinking.

Many within the reform movement now say, while good teachers are essential to helping poor children learn, exceptional classroom instruction is not enough to shrink the growing gap between rich and poor children in public education.

They argue that public education needs a new kind of overhaul, one that acknowledges the critical need for one-on-one attention among children who grow up in poverty. This model has several names. Some call these models “wraparound schools.” Some call them “community-based schools.” But the idea is that public schools must begin to accept a role long left to the home front: child rearing.

And it’s an idea that has attracted attention as examples have popped up, been studied and shown to be a benefit to poor children, as well as a cost savings to school districts in the long run.

For Swafford, who came to CGLA after working as a teacher, principal, administrator and community college vice president, the approach was beautifully logical. It simply called on public schools to offer poor children the supports middle- and upper-class parents provide for their own children.

CGLA chorus teacher Charles Collins, center, talks to students Glendy Perez, left, and Carmen Gonzalez after chorus class at the school in November.

Sure, basic academic skills and a high school diploma could lead to a $10- to $12-an-hour job. But those aren’t real family wages in 2016. The math doesn’t work. It’s not enough, and Swafford knows it.

Children with Kenyetta’s background didn’t arrive at adulthood with the safety net that children of the middle class take for granted. They weren’t given laptop computers at graduation and hand-me-down cars at age 16.

Kenyetta’s father, for example, had supported his family for 14 years with just a disability pension amounting to less than $15,000 a year. After being shot as a teenager in the Westside, he had been riddled with pain and used a wheelchair for decades until he died from medical complications related to the shooting, leaving Kenyetta and her younger sister with nothing. Her mother worked off and on over the years but had difficulty coping after the death of her longtime partner.

While many middle-class teenagers bank checks from part-time jobs that their parents hope will teach them the value of work, teenagers with earnings, like Kenyetta, have to help pay their parents’ and siblings’ bills.

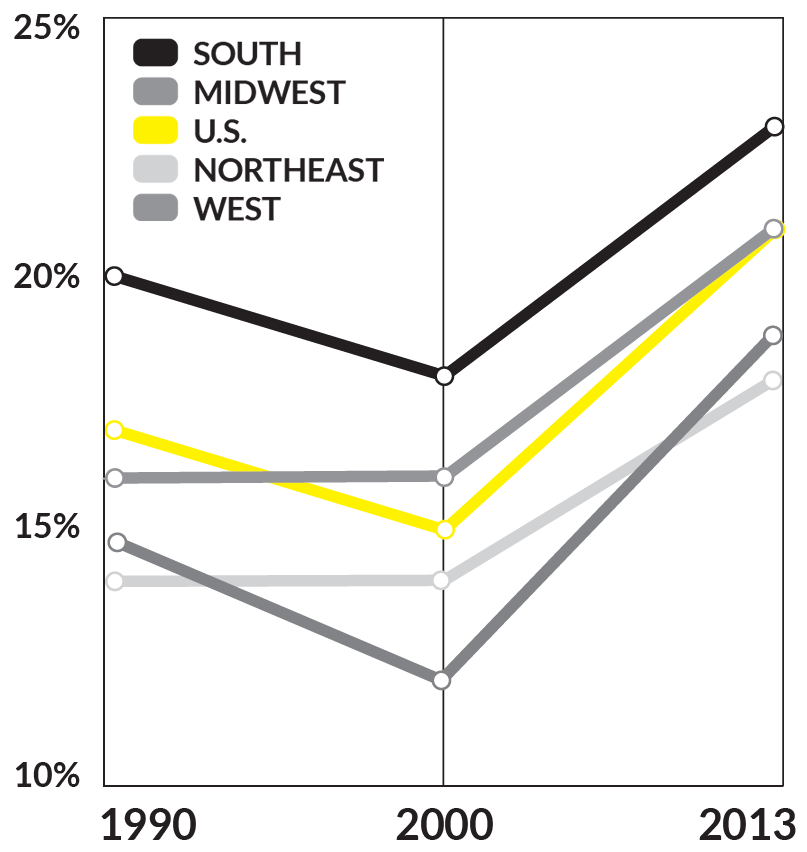

Source: U.S. Department of Commerce. Includes the percent of 5- to 17-year-olds in families living in poverty.

So when it came time to grow up, get a car and move out, there would be no family money in reserve for down payments or deposits. Without parents or grandparents with good credit, finding a co-signer for a used car loan would be difficult, and high-interest, buy-here-pay-here car lots would be the only option.

With a full-time job making near minimum wage, Kenyetta wouldn’t make enough to meet the income requirements of most apartment landlords, Swafford knew. For a rental costing just $550 a month — a price on the low end of the market — her income would need to be $1,650 a month, or three times rent. With a $10-an-hour, full-time job, she would bring home only $1,600 a month before taxes.

And those who found temporary financial stability often slipped. With no margin for error, a single misstep — a broken-down car or unexpected medical bill, for example — could foil any plan of escape.

Some who live in the Westside, where Kenyetta grew up, could tell stories of young adults who lost jobs because they didn’t have enough money to buy a car and the rides they did find were either too expensive or not reliable. Some can tell stories of young men who took undeserved criminal charges to protect a person they loved, even though they knew it would strip them of future opportunity. Some can tell stories of young women with professional ambitions who stumbled off their path after an unplanned pregnancy. Others know young adults who destroyed their credit by giving money to family members in need while keeping nothing to pay their own bills.

To the neighborhood, they were the smart kids, the good kids. But as adults they were boiled down to what databases knew of them — a credit score, a criminal record, an ACT test result.

Former CGLA student Kenyetta Brown, right, and her friend Brenton Adams dance while Brenton’s younger brother, Brandon Adams, films on his cellphone outside their apartment complex in November. Kenyetta’s family moved to this complex in September, and she now attends Ooltewah High School.

And those facts haunted Swafford. She feared visiting the projects a decade from now and finding Kenyetta still there because she hadn’t pushed her beyond the basics of a high school diploma and passing grades.

Just before the bus left to return the staff to school, Swafford heard her name called again.

“You were my principal at Howard,” said a woman dressed in pajamas and bouncing a baby on her knee.

Swafford squinted, unable to recall the woman’s name.

“Yes … I recognize you,” Swafford said. “What are you doing?”

“I am just trying to find me a job,” the woman answered, downcast. “Do you know of anything?”

“Not off the top of my head,” Swafford said. “But call me, and I will see what I can do,” she added, hoping to rally the woman’s spirit.

Swafford was the proud product of a Tennessee public education. The daughter of working-class parents, she often credited a kind teacher in her rural hometown of Bakewell for noticing her talents and pushing her toward a state university even though it appeared to be financially out of reach. It was because of that attention that she chose to spend her career in Tennessee schools.

And she never stopped hoping the children she knew along the way had been left better off because of her efforts.

Swafford strained her face as she passed through the housing projects, passing lines covered with wet laundry snapping in the wind. Behind her, the woman with the baby became a speck in the distance.

Still, Swafford didn’t look back. That past was a painful reminder of what was truly at stake.

She just kept moving, watching the grass pass under her feet.

GLA didn’t

start with Swafford.

GLA didn’t

start with Swafford.

The idea and the seed money came from Sue Anne Wells, a very private philanthropist and prominent alumna of one of the city’s three prestigious and high-dollar prep schools.

Wells, who had long run a nonprofit that rescued mustangs, wanted poor girls in Chattanooga to have the kinds of opportunities, connections and supports that local prep schools and public schools in higher-priced neighborhoods offered the children of the well-to-do.

But when its first local iteration failed to meet expectations, Wells brought Swafford in to help start from scratch.

In 2012, the charter school was on the brink of closure. In one year, though, under Swafford’s leadership, the school came off the state’s list of failing schools and was named one of Tennessee’s most improved. The next year, CGLA received the state’s highest recognition for progress again.

Test results for 2014 show students increased their math proficiency by 36 percent, their science proficiency by 30 percent, their Algebra II proficiency by 64 percent and their biology proficiency by 56 percent.

Enrollment jumped as well, from 75 students when the school opened in 2009 to almost 300 in 2014.

And the success brought recognition to the school. So throughout her tenure, Swafford offered tours for the curious.

To start, she took visitors to a room off the front office and asked them to stare at a large, concrete wall covered in data. Magnets, stacked in rows, represented the academic status of individual CGLA students, Swafford explained, and their progress was updated, tracked, color-coded and studied by staff to develop individualized strategies for every girl.

The data told amazing stories, she said.

Next, she routinely offered a sermon of sorts on data, accountability and a culture of no excuses, using the language of so many other hard-charging school reformers.

When she took over CGLA, she told the entire staff to reapply for their jobs, she explained to visitors. It was the best of the four options the state gave her to produce a turnaround, she said.

Fifty percent of the staff were hired back, she added, but only after they passed her one-question test.

“How much responsibility is it of yours that students at CGLA are academically successful?” she said she asked each candidate.

“I love to hear 100 percent, but I will accept a 90 percent or higher,” she told visitors. “I don’t hire people that say you can take a horse to water but you can’t make them drink.”

Student teacher Cara Cote helps Mecca Sales with an assignment next to Merli Ambrosio while teacher Katie Warwick continues to lead class in December at CGLA.

After watching the reform agenda trickle down and whipsaw schools and chew up superintendents for 30 years, Swafford had come to believe children were leaving high schools and living in poverty not because of terrible teachers but because America’s education ills had long been misdiagnosed.

It was true that the U.S. had fallen behind in international testing and that too many students were unable to translate their education into a good-paying skilled job or a ticket to higher education. But many, including Swafford, had begun questioning the widely accepted narrative that cast schools as incompetent poverty machines.

But ultimately, it was data, not a sympathy for educators, that became her guiding light.

In recent years, thorough study of national education data showed public schools were actually serving many students quite well . Federal data showed more students were graduating from high school than ever before and that all age groups had higher average test scores in reading and math than they did nearly 45 years ago. Public schools have made enormous strides in closing gaps between minority and white students as well.

But the gap research showed had widened, however, was the one between rich and poor students, of all races.

Source: National Survey of Children's Health

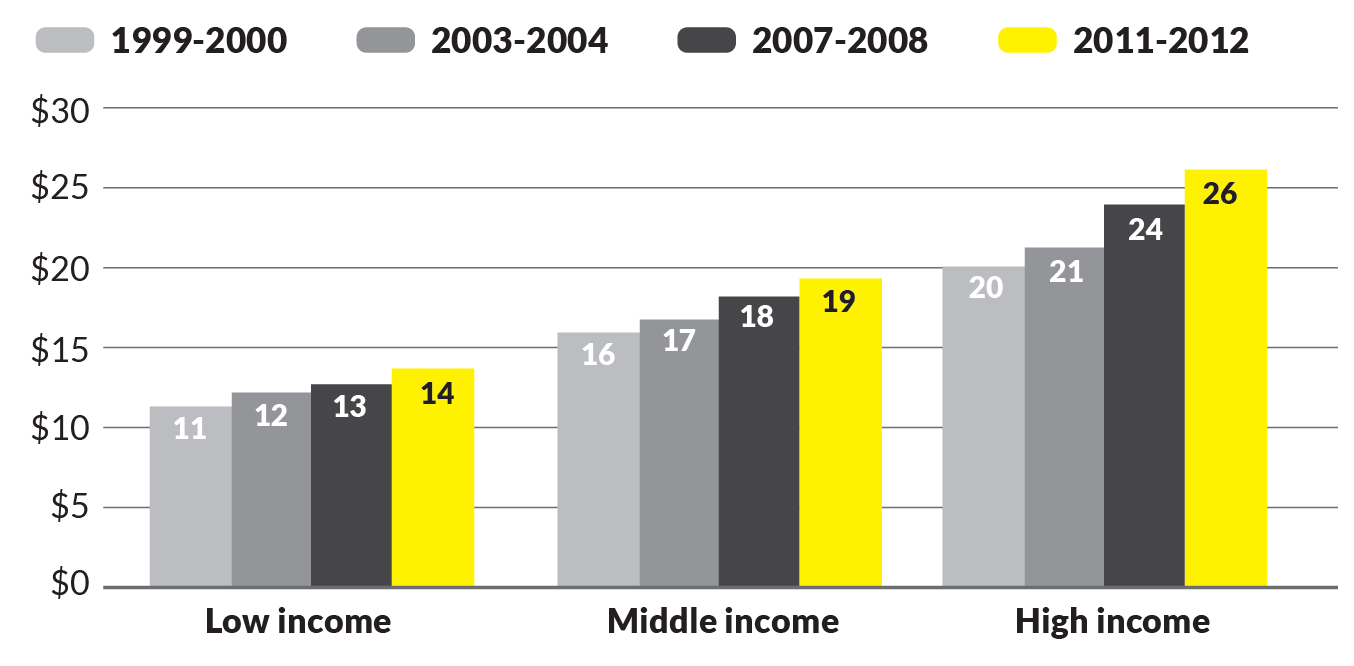

Previous generations of college graduates were waiting later to have children and were having fewer of them. With two incomes, more education and more time, these parents were heavily investing in developing their children and unwittingly setting a standard others could never reach, experts who studied the trend concluded.

Middle- and upper-class parents, most of whom lived outside the inner city, also invested in their children’s public schools, while opposing property tax increases for schools overall.

Schools such as Signal Mountain Middle/High School and Normal Park Museum Magnet School, both educating small shares of poor and struggling students, had community foundations with money that filled the gaps the state couldn’t cover financially.

The Mountain Education Fund, for example, raised a half million dollars a year through parent fundraising to support schools in Signal Mountain, one of the county’s wealthiest communities. Yet, Hilary Smith, a longtime guidance counselor at Howard High School, which was tasked with educating the most disadvantaged students in Hamilton County, said staff at Howard had to beg community nonprofits or individuals for donations of notebooks and pencils. Almost every student at the school came from a struggling household and often had few of the supplies they needed for their schooling, she said.

So the divergent outcomes of high poverty and low poverty schools were no surprise, experts said.

In the 1960s, poor children trailed rich children by about a year academically. By 2013, the gap was closer to four years, according to research by Sean Reardon, a national expert on education inequality and the author of a 2012 study that raised questions about the conventional wisdom of policymakers, politicians and educators.

Other research backed his findings.

So, in Swafford’s mind, schools didn’t create this achievement chasm between the middle class and poor. They inherited it.

Even at schools in more affluent districts, when you stripped away their middle- and upper-class performers, poorer students still struggled. In other words, a rising tide did not lift all ships.

he fall of

2015 was a turning point for Tennessee schools.

he fall of

2015 was a turning point for Tennessee schools.

A new wave of state standards was coming, and a new test, called TNReady, would measure students’ logic and problem-solving skills, as well as their root memorization of words, concepts and facts.

It was a concerted effort to once again bring Tennessee more in line with national standards, but it would strip any varnish left on the state’s public education system. It would also be a major test for CGLA.

For two years, Swafford and her staff worked tirelessly to teach students to conquer the TCAP exams. She cared about the testing game, not because she wanted to sell a school turnaround story but because improving test scores meant she could keep the school open and convince supporters to provide and sustain resources that ensured her students could have what they needed for a real chance at college and higher-wage jobs.

Children in stable households, for the most part, had adults who looked after them and knew the prerequisites for success. So the adults at CGLA had to uncover gaps in learning, she told staff members.

(Top) Teacher Katie Warwick gives student Lakahia Havis a little extra encouragement in December at CGLA.

(Bottom) A list of words and phrases CGLA students aren’t allowed to say is displayed prominently in the chorus room of the school.

If a student spoke with improper English, they had to correct it.

If a student used fists to resolve an argument, they had to explain a better approach.

If a student didn’t have help with homework at home, they had to make sure they finished it with tutors at school.

If a student couldn’t afford an extracurricular activity, they had to find the money.

If a student didn’t have a ride home after school, they had to secure transportation.

If a student was sick and their parents couldn’t afford medical care, they had to find someone to help get them treated.

“In loco parentis,” Swafford would say, quoting a Latin phrase that meant “in place of a parent.” “When students are in our building, we treat them like they are our kids,” she said.

Asking her teachers and staff to cross the line into substitute parenting was hard. She knew it was a heavy burden because she experienced the late hours, weekend work and constant worry along with them.

Still, she didn’t expect the school to do it alone.

By Swafford’s reckoning, it cost $11,370 to educate each student each year at CGLA, a far cry from the $7,600 per student allotment Swafford received from the state of Tennessee. So, from the minute she took over CGLA, she began asking people to give money that would bridge the gap between what she had and what she needed.

She and her staff wrote grants for uniforms, for gym remodeling, for travel, for curriculum coaches, for professional development and for before- and after-school transportation. If there was a need, a grant was written.

Last year, a student told Swafford she was behind in statistics class because she had no Internet at home and couldn’t complete her homework.

“Internet access is no longer a nicety,” Swafford told potential donors not long after. “It is a necessity.”

(Top) Merli Ambrosio picks up breakfast before school begins in November at CGLA. Every school morning starts with a free breakfast for all students.

(Bottom) CGLA senior Mai Dupre works on her school-issued laptop during science class in December.

Eventually, someone committed to rallying supporters to raise money for a program they would call “Backpacks for Success,” which would offer students a backpack filled with $1,500 worth of clothes, Internet cards, shoes, hygiene products and food cards.

Swafford welcomed speaking requests. She worked the luncheon circuit and made appointments with anyone she thought had something to offer her students. And if a person couldn’t or didn’t want to give money, that was fine. Swafford would just ask them to volunteer.

She decided every student at CGLA was going to have a mentor to meet with regularly. When she didn’t have enough adults in her building for each girl, she called for adults on the outside to step up. Professionals were invited to come by the school to talk about their careers, to let students tour their offices or shadow them at work.

“If you don’t feed the human spirit, then how can you expect to drill down to Algebra I?” she asked, explaining why she insisted teachers and staff nurture “the home side of school,” as she called it.

And she built the CGLA “wraparound” model because she wanted students to leave the school with more than a basic collection of facts they memorized and regurgitated for a timed test. She wanted them to love learning enough to pass it on to their children. She wanted them to face tough situations and maintain their grace and dignity. She wanted them to understand what it took to navigate an intimidating professional world that required a different skill set than their neighborhood survival instincts.

(Top) CGLA students Ambria Sydnor, Shema Silvestro, Aniyah Clemons, DaLiyah Ellison and Raven Griffin walk down the steps to the buses for a school trip to visit the UTC campus in August.

(Bottom) Amir Williams hugs a friend during class change in December at CGLA.

She wanted them to see jobs in engineering, math and computer science as realistic and attainable, and not just the domain of wealthy children groomed for intelligence from birth.

In short, she wanted to send them into the world with the same tool kit middle-class children from affluent suburbs just miles down the road had when they left home.

Yet, it was a balancing act. While students needed life skills to plant themselves in the middle class, they needed better test scores as their seed corn.

So with the same vigor the staff mustered to attack TCAP, they began preparing for the first TNReady test, which students would be required to take only five months after starting school late last summer.

On the first day of school, Swafford sent students on tours of local colleges but also made them take a TNReady practice test to see how hard their climb would be. When she discussed results with students afterward, one voiced frustration with a question. She asked Swafford to explain the definition of a “round trip.”

“If you go somewhere and don’t come back, what is that?” Swafford asked, looking for someone to chime in with the answer “one way.”

Instead, there was silence.

These children didn’t travel on airplanes. Many of their parents didn’t even have cars. Phrases like “one way” or “round trip” weren’t used in their worlds, she realized.

The moment ignited a strange mix of anger and resolve in Swafford. The education system thoughtlessly stacked disadvantages against certain children, but they would try their hardest to knock them down, she told her staff.

Teachers hung posters all across the school with definitions for commonly tested vocabulary words. They planned curriculum so that test concepts were woven into everything from labs to after-school activities.

“At CGLA, field trips are not in our vocabulary,” she told staff. “We do expeditionary learning. If you leave the building and you haven’t taken your (state testing) standards with you, don’t go.”

She told a local nonprofit she needed more help and got money to employ a data expert she called a “stratestician,” who could comb through students’ test scores and drill down to find each student’s strengths and deficiencies. It would be easy to write off the first year of TNReady and let the year be a wash, but her students, barrelling toward graduation, couldn’t afford the setback.

So Swafford pushed college prep even harder.

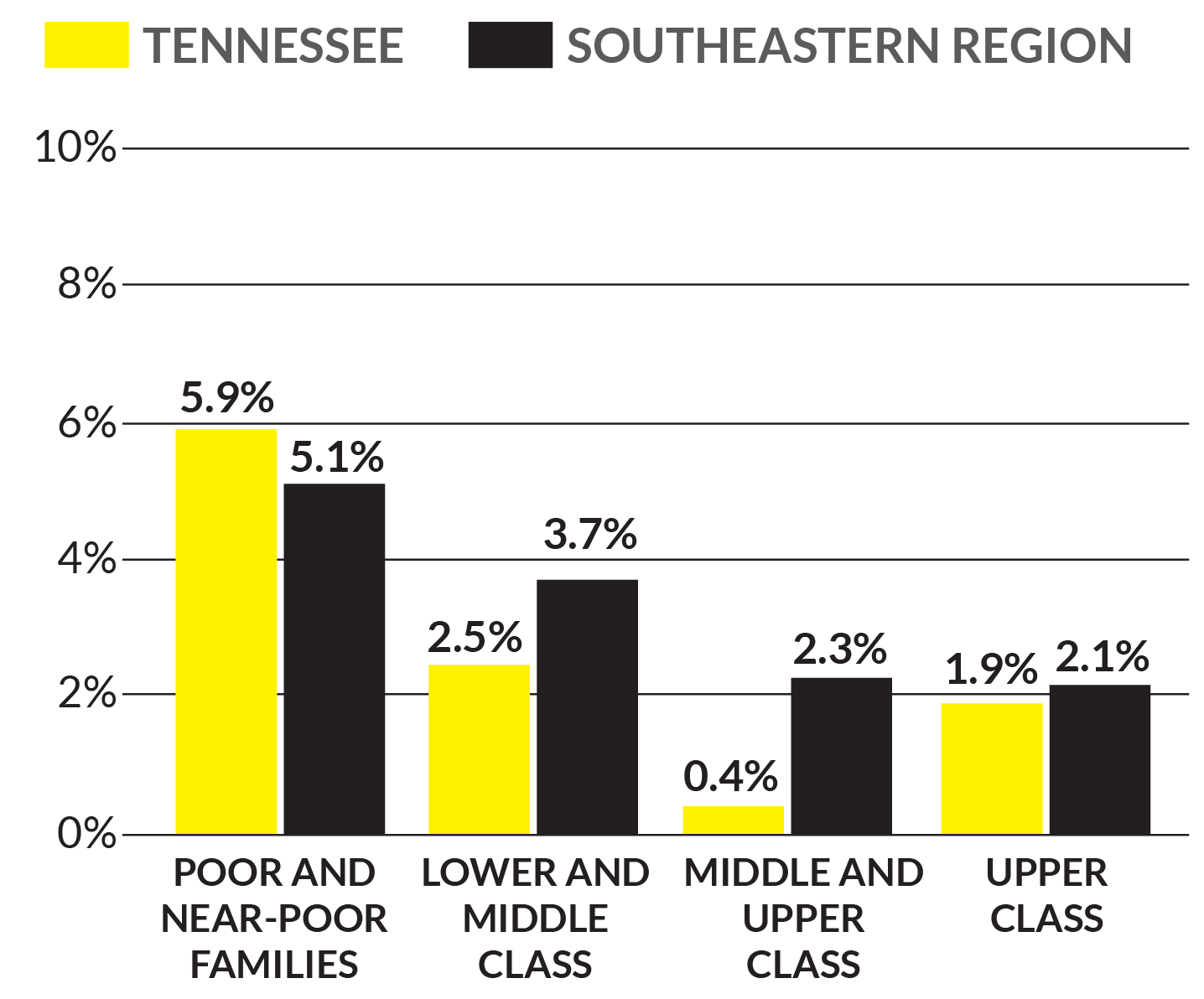

Source: U.S. Department of Commerce, Census Bureau, American Community Survey (ACS), 2013

While learning to take TNReady, the girls at CGLA also took ACT prep courses and practice tests — both funded through grants — to help them secure the highest scores.

After school began, one student told Swafford she didn’t want to take the test a second time as a senior, but Swafford wouldn’t hear of it. She had recently calculated the financial gap the girl would face if she didn’t get a very sizable scholarship that covered housing and living costs as well as books and classes.

“She needs to take this test again,” she told the girl’s mother over the phone. “I need you to back me.”

At the entrance of the school, she arranged little white letters in a black box to read “25 and up club.” ACT administrators consider a score of 19 college ready, but Swafford knew they would need higher than that to get the financial support necessary to even sign up for college classes.

Source: Federal Interagency Forum and Family Statistics. America’s Young Adults: Special Issue, 2014, from U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, National Postsecondary Student Aid Study.

Very few urban schools in America can boast high scores on college prep tests. In fact, many charter schools or public schools that have earned recognition for state testing gains were often undone when ACT scores were released.

Behind closed doors, many in Chattanooga watching Swafford wondered if her experiment was doomed.

But she was sure she would see young women in the spring’s graduating class — the first group to spend ninth through 12th grade at CGLA — earn merit-based scholarships or full rides.

And if she hadn’t pushed them that high, then the school had failed, she believed.

A student is reflected in a board at the CGLA main entrance in December.

One weekday in October, a woman with a local golfing nonprofit followed Swafford through the halls of CGLA.

After Swafford finished her data-soaked intro, she took the woman from classroom to classroom.

She assumed visitors expected dumbed-down classes, broken equipment and harried teachers preoccupied with managing unruly behavior. But what they found instead was a well-oiled machine.

Designated classroom ambassadors, wearing crisp, navy blue blazers saw the school leader coming and jumped up, hurriedly composing themselves, tucking in shirts, smoothing flyaway hair.

At the door, they offered a professional greeting and briefly explained the day’s lesson, as if on cue.

“We are learning about Martin Luther and the Protestant reformation,” one girl said.

“We are making tennis shoes and talking about product development,” another said in another classroom.

Before Swafford took the visitor to the next class, the girls locked eyes with Swafford, briefly searching for a sign of approval. She wasn’t one for excessive praise because she knew the real world wouldn’t accommodate insecurity. Still, she left them each with a hint, a wink or a nod, something to signal they had done their part.

“This is wonderful,” the woman said before leaving. “Let me know what we can do to help.”

“I will,” Swafford said, knowing she had just made another ally for her girls, who needed all the help they could get.

n a downtown

diversity panel several months ago, Swafford was asked by a moderator what other schools needed to do to be as successful as CGLA.

n a downtown

diversity panel several months ago, Swafford was asked by a moderator what other schools needed to do to be as successful as CGLA.

“I don’t know what they should do,” she said, choosing her words carefully. “We are just trying to be the best all-girls charter school in Highland Park.”

It was a nuanced answer, for sure. It was also an answer that revealed her deep frustration with how ridiculously over-complicated the debate around urban schools had become. She assumed people wanted to hear that charter schools or single-gender schools or visionary leaders or accountable and incentivized teachers were the silver bullet. But she couldn’t.

Flexibility, leadership, business-like accountability and sound pedagogy were essential if schools were going to improve, but that would never be enough, she believed.

The fact is, students need love, encouragement, financial backup, transportation, food, clothing, shelter, peace of mind, a computer, Internet, forgiveness for their mistakes, inspiration, exposure, challenge, moral guidance and lessons in resilience, as well as solid classroom instruction.

It’s a list middle-class parents know intuitively.

So why, she wondered, did so many think there was a shortcut for children in poverty?

There wasn’t, she believed.

All across the country, in and outside of education, smart people were coming to the same conclusion. And their voices were getting louder as research findings continued to challenge the impact of charter schools, turnaround teachers, value-added measures measures and foundation investments. If you wanted to attack poverty’s toxic impact on schooling, your only tools are unrelenting hard work and individual attention, they argued.

(Top) Tasha Kunesh-Kurtz listens intently to assignment instructions in December at CGLA.

(Bottom) Sixth-grader Ziayah Glass peeks through a hallway window to the busy street outside CGLA in December at the school.

Diane Ravitch, an education historian and policy analyst who worked in both the Clinton and George W. Bush administrations and once backed No Child Left Behind, school choice and high-stakes testing, is among many who turned on the privatization movement and began to argue fiercely against it.

“Reformers say that American education is failing. They say that it is obsolete. They say that we spend more and that achievement is flat,” said Ravitch in a speech to educators three years ago. “It’s the big lie. They are wrong!”

“The test scores of American students are at their highest point in history. The test scores of white students, black students, Hispanic students and Asian students are at their highest point ever,” she added, citing federal data.

While other developed nations might out-score American students, none have the rate of childhood poverty that American schools are combating, she said.

“Struggling schools enroll the students with the greatest needs,” Ravitch added. “We must ask why the world’s richest, most powerful nation looks away from the needs of its children.”

More thorough and long-term research is needed to determine whether an investment in community schooling or wraparound schooling will pay off for struggling school systems and poor children, but the current body of evidence indicates that it might.

In 2014, Child Trends, a nonprofit, nonpartisan Maryland-based research organization, crystallized what is known about the model and reported that the approach is firmly rooted in the science of childhood and youth development and does seem to contribute to academic progress.

Eleven evaluations of three models showed that integrated support decreased grade retention and dropouts and increased attendance, math achievement and overall GPAs. Preliminary studies also found the model, while more expensive upfront, saves money over time.

Three long-term studies showed the return on investment ranged from more than $4 saved for every $1 spent to almost $15 saved for every $1 spent.

“We have to create a new type of school because schools aren’t designed for this,” said Robert Balfanz, a senior research scientist at Johns Hopkins University School of Education, who is researching the impact of integrative supports in schools.

“But no one wants to accept the degree of challenge,” he added. “We are still hoping for the one-off solution.”

n January,

before the spring semester was underway, Swafford invited two students to come with her to a meeting with the school’s foundation board to give board members the student perspective on CGLA.

n January,

before the spring semester was underway, Swafford invited two students to come with her to a meeting with the school’s foundation board to give board members the student perspective on CGLA.

She had no idea what the girls, a junior and a senior, would say. While she wanted her students to represent themselves well, she wanted their ideas and thoughts to be their own.

Keosha Cross was one of the two. Keosha briefly attended CGLA before Swafford arrived, but returned to finish her high school education as a junior. When she stood in front of the board members and Swafford, she was nervous because she had never spoken to a large group before.

Still, she spoke from her heart.

The school had given her something extraordinary, she told those listening that day.

Keosha had always been a student who straddled the academic line, not quite behind, but not quite ahead. In sixth grade, she had tested as basic in math and reading. When she took the ACT as a junior, she made a 19, just enough to be considered college ready.

At a lot of public schools where disadvantaged students struggle to reach even basic comprehension and a middling score on college admission tests, her results would have certainly been considered good enough.

Yet, at CGLA, she said, nothing she ever did was good enough.

It was easy to assume that the CGLA staff’s constant insistence on high performance discouraged students who already had so many hardships to overcome. But Keosha said she needed the push.

Swafford, as well as her teachers, saw their students’ value and refused to give up until they saw it, too.

When she got a 19 on the ACT, she went to Swafford to tell her the news, but got a wake-up call, she told the board that day.

“It isn’t good enough,” she said Swafford told her.

Then, when she got a 21 on her next try, she was sure the school’s executive director would be pleased.

“It isn’t good enough,” she said Swafford told her, again.

And Swafford was right, she said. The next time Keosha took it, she made a 24, enough to get into almost any college she wanted.

And she wouldn’t be the only one to leave CGLA with a shot at a real middle-class future.

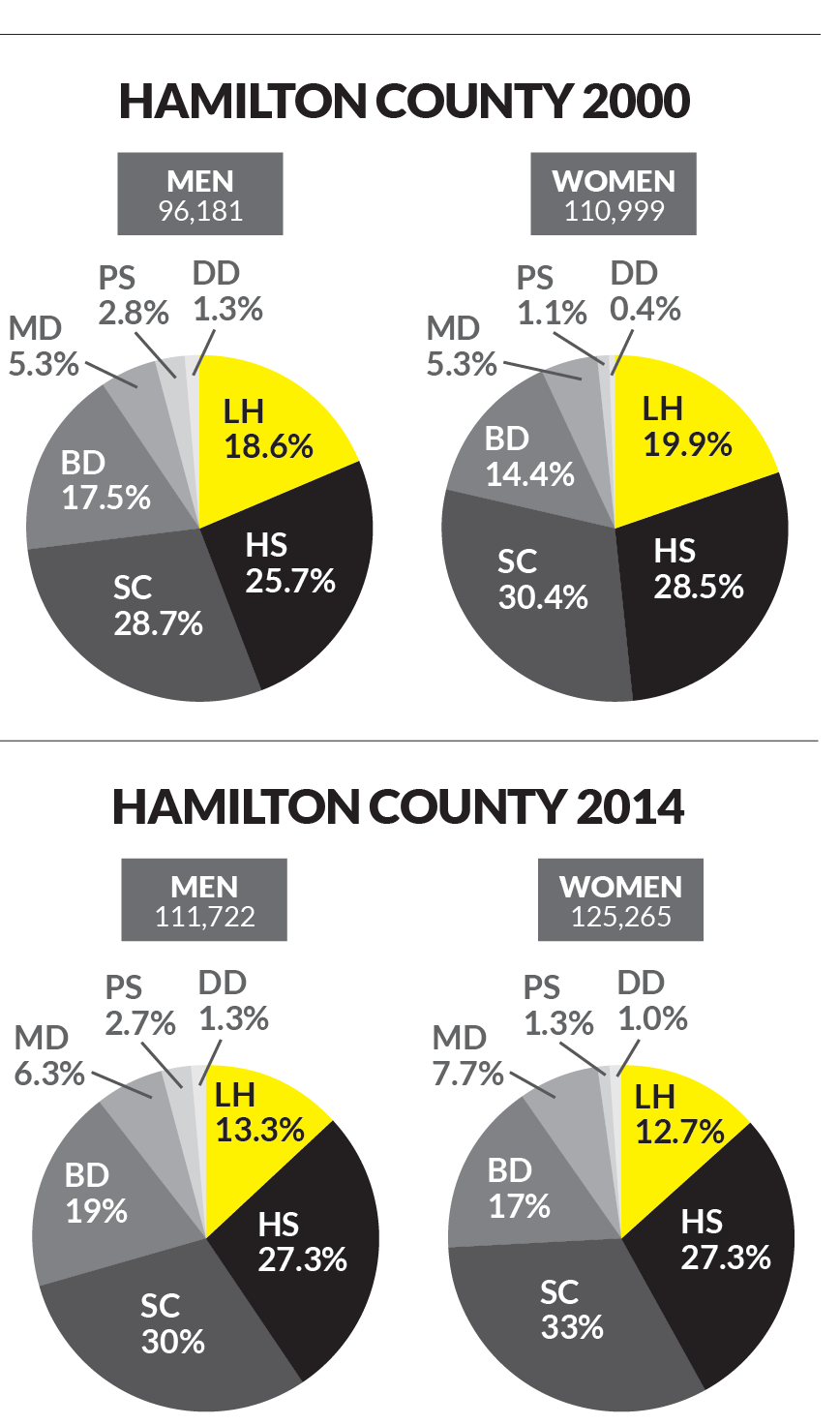

Source: U.S. Census Bureau *Numbers have been rounded

When Swafford came to CGLA, the school hadn’t graduated anyone who was college-ready. Among the graduating class of 2016, however, 9 of the 21 seniors, almost half, had high enough ACT scores to be considered ready for the rigors of college-level courses.

Students not considered college-ready weren’t being left behind. Swafford met with each of them and had them take personality tests and interest inventories. Every child would get some training after high school, she told the girls and their parents, and the surveys would help them think through all their options.

At home alone, when she thought about the accomplishment, Swafford couldn’t help but return to a moment, a few years ago, when 48 percent college readiness seemed like a pipe dream.

She and a few others, including Wells, were finalizing the school’s mission statement, and Swafford, not surprisingly, wanted the statement to be a bold one.

Sherry Pulliam speaks with her daughter Jasmine right before she leaves for her freshman year of college at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville. The Pulliams struggle with money, and Jasmine wants to become a doctor so she can have a good, stable income when she’s an adult.

“Inspire hope so each girl has the possibility to change her trajectory in life and empower her to possess infinite choices in the future,” she said in her office one day, trying to recite the statement from memory.

Her girls were amazing, she said. But her girls were a light, too.

They were illuminating a path forward for their families and their neighborhoods, but they were also showing all of Chattanooga what was truly possible.

Other girls, and even boys, would watch them and follow, Swafford thought, and together they would shine so brightly they could no longer be ignored.

Now, when students walk by the black box at the front of the school and read the words “ACT 25 and Up Club,” there are five names underneath.