N AUG. 28, 1995, Brian Fikkert gathered the courage to send a letter detailing why he thought the modern evangelical church was broken and had forgotten a key piece of the gospel.

N AUG. 28, 1995, Brian Fikkert gathered the courage to send a letter detailing why he thought the modern evangelical church was broken and had forgotten a key piece of the gospel.

It was a revelation that began in his teenage years just as the cultural wars were raging. He read a book by theologian Ron Sider, one of the few people in the late 1970s calling for evangelical Christians to stand up to systemic injustice and implement policies to care for the poor. But Fikkert had witnessed the backlash as some evangelicals called Sider a left-wing socialist, discounting his message as political propaganda.

But his words stuck with Fikkert, who chose to study economics instead of going to seminary because he wanted to learn how to alleviate poverty.

After earning his doctorate in economics at Yale in 1994, he began to teach and do research at the University of Maryland. But he became discouraged by how poverty was reduced to math equations and statistical analysis. On Sundays at his Presbyterian church, he grew weary with how Christians approached the poor.

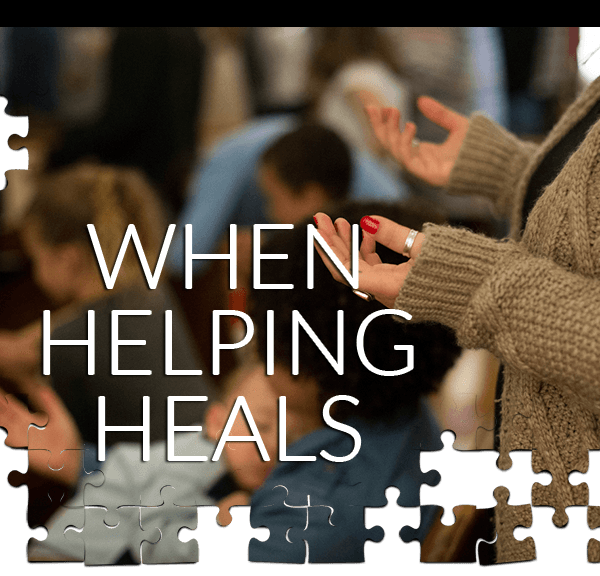

Brian Fikkert, second from left, addresses a crowd in a church in Kampala during a mission trip with his family to Uganda in 2006. With him are, from left, Helen Oneka, his children Jessica, Anna and Joshua, and his wife, Jill.

Turn to Jesus, the deacons told the single mother who came knocking on the door asking for help to pay her light bill. They would help her, yes, but then they acted as if she only needed a spiritual cure to solve her problems.

This attitude struck Fikkert as a tainted view of the gospel. To him, Christians were acting like they were closer to God because they had been blessed with comfortable lives and stable families. They appeared to feel as if they had earned what they received; and the poor, meanwhile, were dirty and broken and must be far from God.

Fikkert volunteered to teach a Sunday school class focused on teaching the purpose of the church. This led him to study the life of Christ to see how the church should follow in his footsteps. In the Bible, Fikkert read how Jesus healed the blind and healed their souls. He read how Jesus commanded a lame man to walk and forgave his sins.

“The kingdom of heaven is at hand,” Jesus said in Matthew 10:7.

Fikkert began to see how Jesus had given the answer 2,000 years prior: Grace precedes salvation.

In Fikkert’s understanding of the Bible, Jesus came to Earth to restore the earthly world as well as the life to come. But evangelicals were fixated on the second part of his message. They were waiting for heaven but not trying to restore the brokenness on Earth as Christ had done, Fikkert reasoned. And in the process, they had forgotten their own brokenness and ignored Bible passages in which God warned he would close his ears to the prayers of the righteous when they ignored the cries of the hurting and poor, Fikkert thought.

This wasn’t a political argument, conservative vs. liberal, he concluded. This was the central message of the Bible. Wanting to share what he was thinking, he typed a letter to a friend who worked at a Christian college 600 miles away in Chattanooga to discuss what could be done to help Christians change their hearts about the poor.

“We are good at preaching grace, but we are lousy at demonstrating it,” he wrote.

“I dream about developing a course/program/institute at a Christian college which would explore both the spiritual and economic dimensions of poverty and lay the theological foundations for ministries of mercy to the needy.”

Little could he have imagined how his vision would unfold.

hen the

letter was stamped in 1995 to Covenant College, it was at the beginning of a precipitous decline in the American church.

hen the

letter was stamped in 1995 to Covenant College, it was at the beginning of a precipitous decline in the American church.

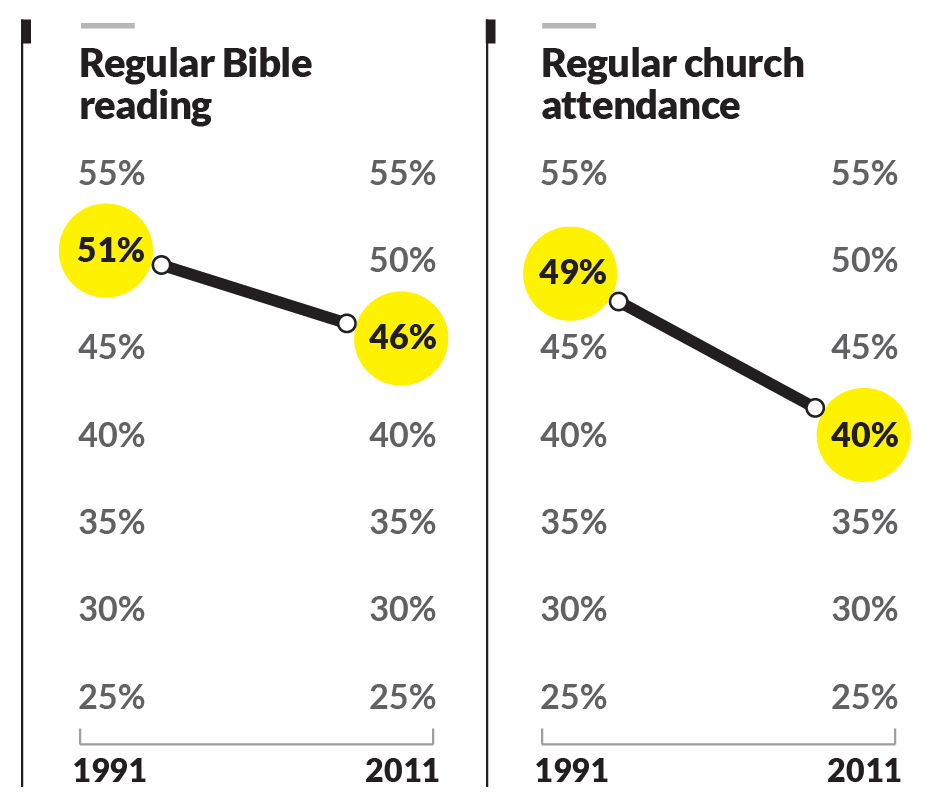

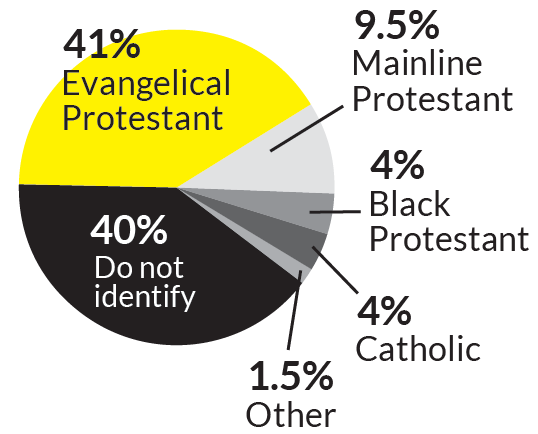

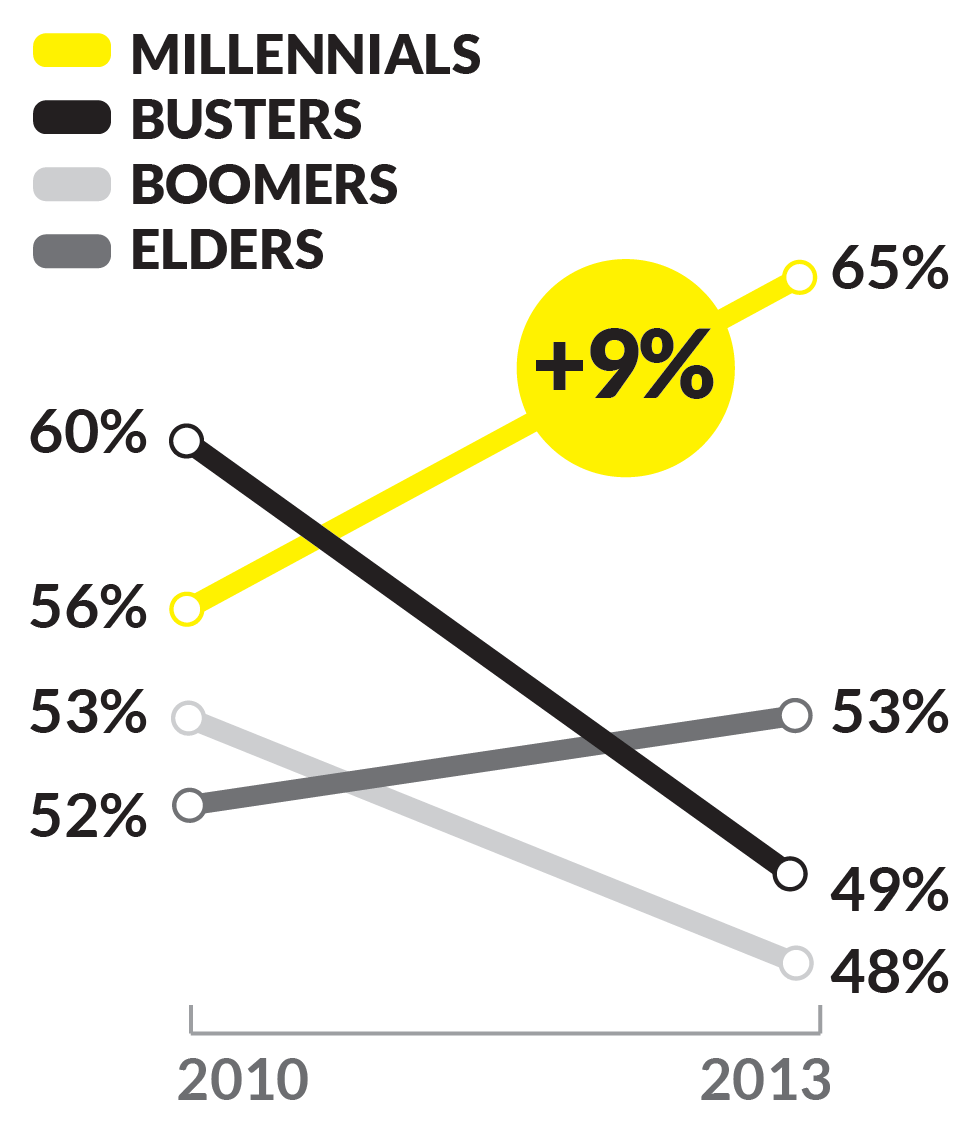

Over the next 20 years, church attendance shrank 9 percentage points, according to Barna Group, a Christian polling firm. Meanwhile, Sunday school attendance plummeted, and volunteering at church drastically dropped, too. Fewer born-again Christians read the Bible, Barna found, and by 2011 only 43 percent of Christians said they had strong belief in the Bible anymore.

The retreat from Christianity wasn’t happening in a bubble, wrote Robert Putnam, a Harvard political scientist, in his book “American Grace: How Religion Divides and Unites Us.” Americans were becoming disconnected and didn’t trust their foundational institutions anymore, including the church.

Source: Barna Group

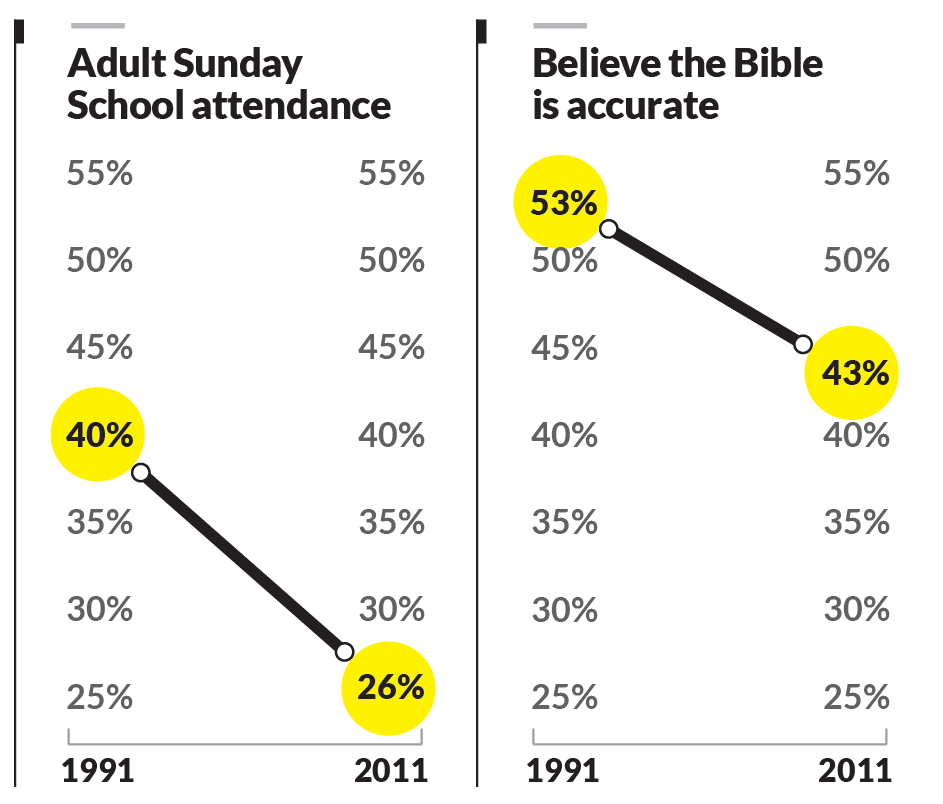

But young people’s rejection of faith went deeper, Putnam argued. The evangelical church was more focused on fighting for morality than compassion, he believed. While churches gave away turkeys at Thanksgiving, organized toy drives at Christmas and helped fund missionaries across the globe to spread the salvation message, the message didn’t translate into grace for the suffering in their own backyards.

Among the growing number of skeptics in America, Barna found the majority thought church members weren’t connected to one another in life-changing ways, did little to add any value to their communities and were led by people who didn’t show love for one another.

Yet when Fikkert began to study the history of the church in America, he realized evangelical Christians had once been beacons of hope in their communities and championed the fight for the poor, believing it was at the heart of the salvation message.

Before the 20th century, evangelicals were on the front lines fighting to improve working conditions for industrial workers, wrote David Moberg in his book, “The Great Reversal.” They created orphanages, set up schools for immigrants, fought for laws to end child labor and founded rescue organizations such as The Salvation Army.

But in the 1920s, disagreement over salvation caused the predecessors of modern evangelical Christianity to shrink from helping the poor out of fear that the social gospel — which focused on helping the poor but not the need for salvation — would spread, Fikkert read in historian George Marsden’s book “Fundamentalism and American Culture.”

Source: Barna Group

An important setback for conservative Christian beliefs played out in Tennessee when all eyes were on the small town of Dayton during the Scopes Trial in 1925. The trial, Marsden argued, represented the great clash between rural, less-educated Christians and the emerging sophisticated intellectuals who had outgrown God. Even though William Jennings Bryan, the conservative prosecutor, prevailed in his argument against evolution in the trial, the public and the press concluded that science had trumped the Bible.

Conservative Christianity stayed in the shadows until it re-emerged with a Southern accent, Marsden argued. In the late 1950s, North Carolina evangelist Billy Graham packed sports arenas nationwide as he preached the New Testament gospel. In the Deep South, Martin Luther King Jr. emerged preaching that God had created all men equal. But Southern pastors focused on the evils of alcohol, gambling, drugs and sexual immorality — even while their African-American brothers were lynched in the streets.

It was Southern Baptist televangelist Jerry Falwell and Conservative media mogul Pat Robertson who mobilized the evangelical church to enter the political arena in the 1970s, as the country experienced a dramatic change in standards of family and sexuality, to fight for what they termed “family values.” And in the movement, the message of forgiveness and grace was often lost, Fikkert said.

When Fikkert examined Jesus’ life, he didn’t see morality and love as being in conflict. He read how piety and worship of God must lead to people who act justly and love mercifully.

It was for those reasons that Fikkert believed the evangelical church needed a wake-up call. Still, when Covenant College leaders offered to give him a platform in Chattanooga, he found himself at a crossroads.

ikkert wanted

the church to change, but he didn’t know if he wanted to be the one to deliver the message.

ikkert wanted

the church to change, but he didn’t know if he wanted to be the one to deliver the message.

He was content at his prestigious research university near Washington, D.C. From the most influential city in America, he consulted the World Bank on its foreign policies. The thought of moving to Southeast Tennessee to teach at a small Christian college sounded like the end of his career.

Covenant College had offered him the chance to develop his own curriculum to teach students the principles of economics through a biblical lens, encouraging them to do good works in their communities. And he would be able to split his time developing a nonprofit that would train churches to care for the poor.

Fikkert’s wife, Jill, made the decision for him. It was the chance of a lifetime, she told him.

In 1997, he moved his family to an early 1900s Victorian-style home in St. Elmo where his street embodied the divide within the city. In his backyard, he played catch with his kids near a long row of trees that separated his up-and-coming neighborhood from Alton Park, one of the poorest communities in Chattanooga. He envisioned the door to his home welcoming both communities.

As Fikkert began the daily commute up Lookout Mountain to Covenant College, he realized he had no idea how to live out what he was learning. He began to meet with community leaders to raise support to open a center that would help churches create Bible-minded programs centered on economic development to help the poor.

Brian Fikkert teaches his final economics class of the fall semester at Covenant College. Fikkert splits his time between teaching, traveling for speaking events for the Chalmers Center and writing books.

Financed with private funds, the facility opened on the Covenant campus in 1999. Fikkert named it the Chalmers Center after 19th-century Scottish preacher Thomas Chalmers. Also an economist and mathematician, Chalmers eradicated poverty in his parish when he asked the government to withdraw and let the church step in.

Like the Scotsman, Fikkert didn’t create the Chalmers Center to increase dependency for the poor but to find ways to help them help themselves.

Internationally, the Chalmers Center’s message was well-received in churches and ministries from India to the Andes. Fikkert and his staff created a savings-based program to help people in Third World countries learn a trade or business skill and learn how to save.

But in America, Fikkert’s message was harder to sell. When he traveled to conferences, only a handful of people sat in the audience. While churches could justify helping the poor starving children in other countries, they didn’t think there was a problem in America.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau

“What was the sin of Sodom and Gomorrah?” Fikkert would ask, knowing his audience would think it was their sexual sins. He would then read from Ezekiel 16:49.

“Behold, this was the guilt of your sister Sodom: she and her daughters had arrogance, abundant food and careless ease, but she did not help the poor and needy.”

But a few years into the new millennium, Fikkert saw a change in evangelical churches’ posture.

He saw what he could only describe as God moving in authors and pastors across the country as Christians began to realize they had moved away from the message of the gospel.

“The Holy Spirit was moving,” Fikkert recalled. A number of authors and people were saying the same thing: “If I’m a follower of Jesus, I have to care about poor people.”

God’s heart was for the poor, argued authors such as John Perkins, a Baptist minister.

Others, such as evangelist Ralph Winter, who 30 years prior had mobilized churches to send more missionaries to groups of unreached people across the world, wrote how he was afraid the church had become greedy and self-absorbed. “Evangelicals fritter away more money per year than Bill Gates gives away,” Winter wrote in 2008, a year before his death. “They have been buying boats and second houses and adding on to their homes ... It seems like everyone is thinking about demolishing world problems — except the church.”

Top: Brian Fikkert answers students’ questions during his final economics class of the fall semester at Covenant College.

Bottom: Brian Fikkert talks to students Reid Northcutt, left, and Beka Saylor during his office hours at Covenant College in December. Fikkert, who has cut back on teaching classes to write books and focus on his other roles for the Chalmers Center, says teaching students is one of his favorite jobs.

In response, Fikkert and his staff developed an online course to teach churches poverty alleviation tactics. When requests for material flooded in, they wrote a book. Fikkert and colleague Steve Corbett, who had been at Covenant College since 2001 helping him develop the student curriculum, began to outline what they had learned about the gospel and caring for the poor.

“We are excited about the renewed interest in helping low-income people … but our excitement about these developments is seriously tempered by two convictions,” Fikkert and Corbett wrote in the preface of “When Helping Hurts.”

“First, North American Christians are simply not doing enough. We are the richest people ever to walk the face of the Earth. Period,” they wrote. “Second, many observers, including Steve and I, believe that when North American Christians do attempt to alleviate poverty, the methods often do considerable harm to both the materially poor and the materially non-poor.”

Poverty was about brokenness in the world, but everyone was broken. The gospel message is that Christ came to redeem brokenness and restore people’s relationships with God and each other, Fikkert and Corbett wrote.

Their goal was to sell 10,000 copies, and then Fikkert planned to focus on his research again and pursue global poverty alleviation projects. The week the book went to store shelves in 2009, he took his family to the beach. His assistant called halfway through the week.

“It’s sold 5,000 copies,” he told him.

For the next few months, sales soared past 100,000 copies, then 200,000, then on to become a national best-seller. Churches from Dallas to Ohio began to call by the dozens. It was toward the end of the Great Recession, and families within the church were suffering and more people from the community were banging on their doors crying for help.

What do we do now?, they were asking.

Fikkert didn’t have the staff in place to offer much help.

s the Chalmers

Center grew into a research and training arm for churches to tackle poverty alleviation, Fikkert and his staff wanted to model a program in Chattanooga for churches to copy across the country.

s the Chalmers

Center grew into a research and training arm for churches to tackle poverty alleviation, Fikkert and his staff wanted to model a program in Chattanooga for churches to copy across the country.

Backed with funding from the Maclellan Foundation, they hired additional staff in 2010, including Jerilyn Sanders, who at the time was heading a local inner-city outreach program. Sanders began looking for a bank that could be their financial partner for churches to implement a matched savings account program.

The idea was for the church to help people in poverty save money toward a goal, such as going back to school or buying a car. If they met their goal, the church would match the amount. The goal was to help people to become self-sufficient while building relationships between the middle class and the poor.

Bernie Miller, the pastor at New Covenant Fellowship Church, speaks with Zachariah Laboo, one of his congregants. Miller helped Laboo find a job when nobody else would hire him.

As Sanders met with church leaders to try to sell the idea, she often got blank stares. Leaders were confused by the message of giving more of their time and less of their traditional giving, small cash assistance to the poor. Sanders remembers several pastors saying they could recruit their members to give cans of food and toys and sign up for volunteer work. But asking members for a three-year commitment with people in poverty that required training, large financial commitments from the church and a significant amount of time seemed implausible.

They realized the principles were great in theory but much harder to put into practice.

But Jesus never said it would be easy to follow him, and Christians have long debated what it means to follow in his footsteps with regard to money, wrote David Miller, director of the Princeton University Faith & Work Initiative, in a 2007 paper on wealth creation. Many verses, such as the story of the rich man who asked Jesus what he must do to enter the kingdom of heaven, suggest Jesus calls for his followers to give up everything material to follow him.

“Sell all that you possess and distribute it to the poor, and you shall have treasure in heaven; and come, follow me,” Jesus told the rich man.

Source: Barna Group

But other verses, Miller found, suggest Jesus condemns laziness and wasting God’s resources on idleness and that wealth is a blessing from God. But like Fikkert believed, Miller concluded that wealth is not an obstacle or an offense to faith. Instead, money should be integrated with faith and be seen as a tool like everything else Christians possess, to be used to serve God and others.

Officials at the Chalmers Center decided they needed to get people to understand the basics of money and faith first. So they scrapped their original programs and created a financial class they believed could grow into a movement to help the poor toward upward mobility.

Many churches were already teaching financial freedom classes popularized by financial guru Dave Ramsey, but Sanders found those programs set goals that assumed two-income households and were geared toward the middle class.

Sanders and her team began to write a faith-and-finance curriculum that set realistic goals for single mothers and low-income families. The classes would be for both the material poor and the middle class. Together, they would learn healthy financial principles, discover what God said about money and develop relationships recognizing where each group could teach the other.

Faced with a lack of interest in Chattanooga, they began planning a training event. It would be held at Calvary Chapel on South Broad Street but be open to any church in the country. They had room for about 40 participants but planned for about two dozen.

By the summer of 2012, Sanders’ email account was flooded with requests. Seventy people from across the country wanted to attend.

ix years

after “When Helping Hurts” was published, Fikkert doesn’t have to convince evangelical churches when he travels that God’s heart is for the poor.

ix years

after “When Helping Hurts” was published, Fikkert doesn’t have to convince evangelical churches when he travels that God’s heart is for the poor.

The question has become: How can we do it better?

Across the South, evangelical churches are asking how they can engage in race reconciliation and help their neighbors in need, said Stephen Haynes, a religious professor at Rhodes College in Memphis who has studied the history of religion and racism in churches.

Last June, Fikkert spoke by invitation at the Southern Baptist Convention’s annual conference, where the theme centered on how the church could engage in social justice at home.

Source: Barna Group

The Chalmers Center has witnessed stories of churches shifting millions of dollars to help transform the lives of the poor in their neighborhoods. Since 2012, the staff has trained 232 churches and 144 nonprofit organizations from mega churches to 70-member congregations from coast to coast to use their faith-and-finance class.

They’ve heard many stories similar to North Avenue Presbyterian Church in midtown Atlanta whose 950 members revamped their benevolence giving, then looked within their own congregation and found dozens of members homeless. Church leaders offered the faith-and-finance class. After 10 people graduated, they set up a matched-savings account to help with purchases for goals to get better jobs or to go back to school.

While North Avenue has helped fewer people since revamping its ministry, Matt Seadore, director of the church’s mission programs, said the changes are more meaningful and bring hope to their community.

In many cases, the change in communities across the South is coming from the age group least expected. Barna Group found while more people in America are leaving their faith and say they now identify as atheists, the only generation to increase their evangelism significantly has been millennials, those born after 1980. And a third of young people surveyed in 2015 who said they were engaged in their local church also said they wanted to live out their faith by actively reaching their communities.

These stories excite Fikkert, who has many such stories of graduates of his community development program who have gone on to be part of this movement.

But when he reads the headlines about Chattanooga, he gets discouraged and then angry.

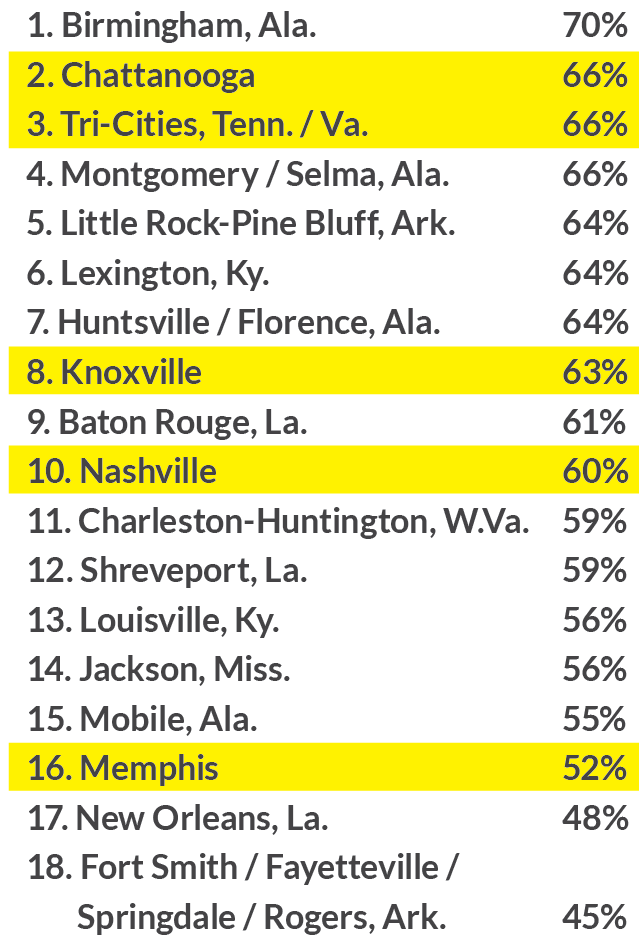

He sees the growing gang violence in his own community and how kids in some countries have a better chance of escaping poverty than the kids born behind his house in Alton Park. Yet Barna Group called Chattanooga one of the most Bible-minded cities in the South.

Source: Barna Group

He asks: How can those two truths exist?

“It would be one thing if Chattanooga were in a place where the church was not present,” Fikkert told a crowd at a banquet several years ago. “But the two Chattanoogas that exist here exist in the heart of the Bible Belt. Our churches are packed on Sunday morning. Do you realize that what is at stake here is not just the children of this city, but the very integrity of the gospel itself is at stake?”

Yet when he questions the churches in Chattanooga, he has to look internally and question his own life.

He never made friends with people in poverty or invited his nearby neighbors to dinner at his house. While his wife, Jill, helps run a health clinic for uninsured children, his own children, who went to the nearby Christian school, didn’t get to know the poor growing up. And while his family worshiped at New City Fellowship, an interracial church, they went their separate ways after the service, keeping up with their busy schedules filled with soccer and basketball practice, teaching and grading papers.

People are busy, Barna found. It’s hard to get to know your neighbor in the modern era with cellphones, smart screens and social media.

But in Fikkert’s office at the Chalmers Center, he sees something that gives him hope. He sees people who have transcended their whole lives, in part, because of his and others like his thinking.

In 2009, John Mark Bowers moved his family to East Lake, one of the most dangerous parts of the city.

Bowers, who writes the Chalmers Center’s curriculum, moved along with about 20 other families who attended New City Fellowship and wanted to build a church where they lived among the people.

Top: Chalmers Center curriculum specialist John Mark Bowers speaks to a luncheon attendee as Nathaniel Bankhead, the center’s U.S. research and training coordinator, listens from the doorway. The gathering held at the Bethlehem Center in January was to encourage local church members and nonprofit leaders who are using the Chalmers Center’s Faith & Finances curriculum.

Bottom: Vladimir Bautista talks to his father, Carlos, during a church service at New City East Lake in January.

They followed the principles of John Perkins, who created a community development movement after he relocated near his Mississippi hometown in the 1960s and helped to rebuild the town by starting a church, day-care center, youth program, cooperative farm and health center. The purpose of relocation is to unite with the local community and then to share resources and rebuild the neighborhood together. It’s a movement growing in Memphis and Birmingham and across the country, as about 400 churches and nonprofits have moved into low-income neighborhoods.

In East Lake, the families are learning together how to rebuild a community.

Some church members purchased rental properties to help create fair housing access. Others have advocated for local leaders to care for the neighborhood and build sidewalks and shelters at bus stops.

When they wanted to get city leaders to fix 12th Avenue, they wrote a song for the children’s choir the church helped create. “There’s a hole in my street,” the children sang. “There’s a hole in my street, and it makes the cars go boom.”

After the video was uploaded to YouTube, the road got fixed.

But the men and women who grew up in East Lake have taught Bowers and the other middle-class residents much more about their own spiritual state.

After living in East Lake, Bowers said he began to see how he, like others in the middle class, worshiped control and how his faith in God was limited. But his neighbors knew the meaning of trusting God to provide for their needs. He saw how Jesus was right when he taught that the places of physical comfort and safety can often be spiritually deadly.

Not everyone will be called by God to live in East Lake, Fikkert admits, but the same attitude of humility and grace has to exist within churches if widespread change is going to come to Chattanooga and the rest of the country as well.

To remind himself, he often returns to a cluster of verses in Isaiah. In the passage, the Israelites go to their prophet to ask why God hadn’t heard them or answered their call. They had done all the Lord wanted, they told Isaiah. They were moral. They made good choices. They followed the rules.

“Will you call this a fast, and a day acceptable to the Lord?” read Isaiah 58:5-8. “Is not this the fast that I choose: to loose the bonds of wickedness, to undo the straps of the yoke, to let the oppressed go free and to break every yoke? Is it not to share your bread with the hungry and to bring the homeless poor into your house; and when you see the naked, to cover him?”

“Then shall your light break forth like the dawn.”