R

ick Watts was waiting for his sandwich at a Subway in Morristown, Tenn., when his wife called him for the last time.

He didn’t know it was her last call and he dismissed it, trying to be polite and stay off the phone at the register.

His cellphone rang at 7:06 p.m. that day, as Tiffany Watts drove home from the Atlanta airport with her two daughters and her mother. The girls, 9 and 11, had just flown in from their dad’s home in California to spend the summer with mom in Tennessee, like always.

Rick Watts knew his family, driving up Interstate 75 in Tiffany’s 2010 Scion, still had hours left to travel. So he paid for his sandwich, took his food to the car and called Tiffany back at 7:09 p.m.

She didn’t answer.

Just then, a tractor-trailer going 77 mph on I-75 in Chattanooga slammed into his wife’s car and seven other vehicles, killing six people, including Tiffany, the girls and Tiffany’s mother — the most deadly crash in Hamilton County in at least 21 years.

At first, Watts didn’t worry when Tiffany failed to answer. He drove to the sleep disorder center in Morristown where he monitors patients overnight and called Tiffany, a nursing student, again.

And then he called again.

Worry crept in. Tiffany rarely went long without checking in or calling back. At a co-worker’s suggestion, Watts looked up online traffic reports and learned about a wreck in Chattanooga.

He picked up the phone and called the police in Morristown. He called the police in Chattanooga. He called the hospitals. A sick feeling grew in his stomach.

But no one could tell him anything.

Around 10 p.m., he ran a quick online search using “Chattanooga” and “wreck” and “I-75” as keywords. And there, in a resulting photo — posted somewhere he can’t remember now — was Tiffany’s black Scion, crumpled.

He pulled up a stock image of a Toyota Scion and put it side-by-side with the photo of the wreck. He reasoned that maybe they were just hurt. He debated driving to Chattanooga. He called and called and called. Hours ticked by during the worst night of his life. He knew, but he didn’t know.

He was angry by the time the officers showed up at the clinic at 6 a.m. and told him Tiffany was dead.

“What about the rest of them?” he asked. “Where are they at?”

The officers just shook their heads.

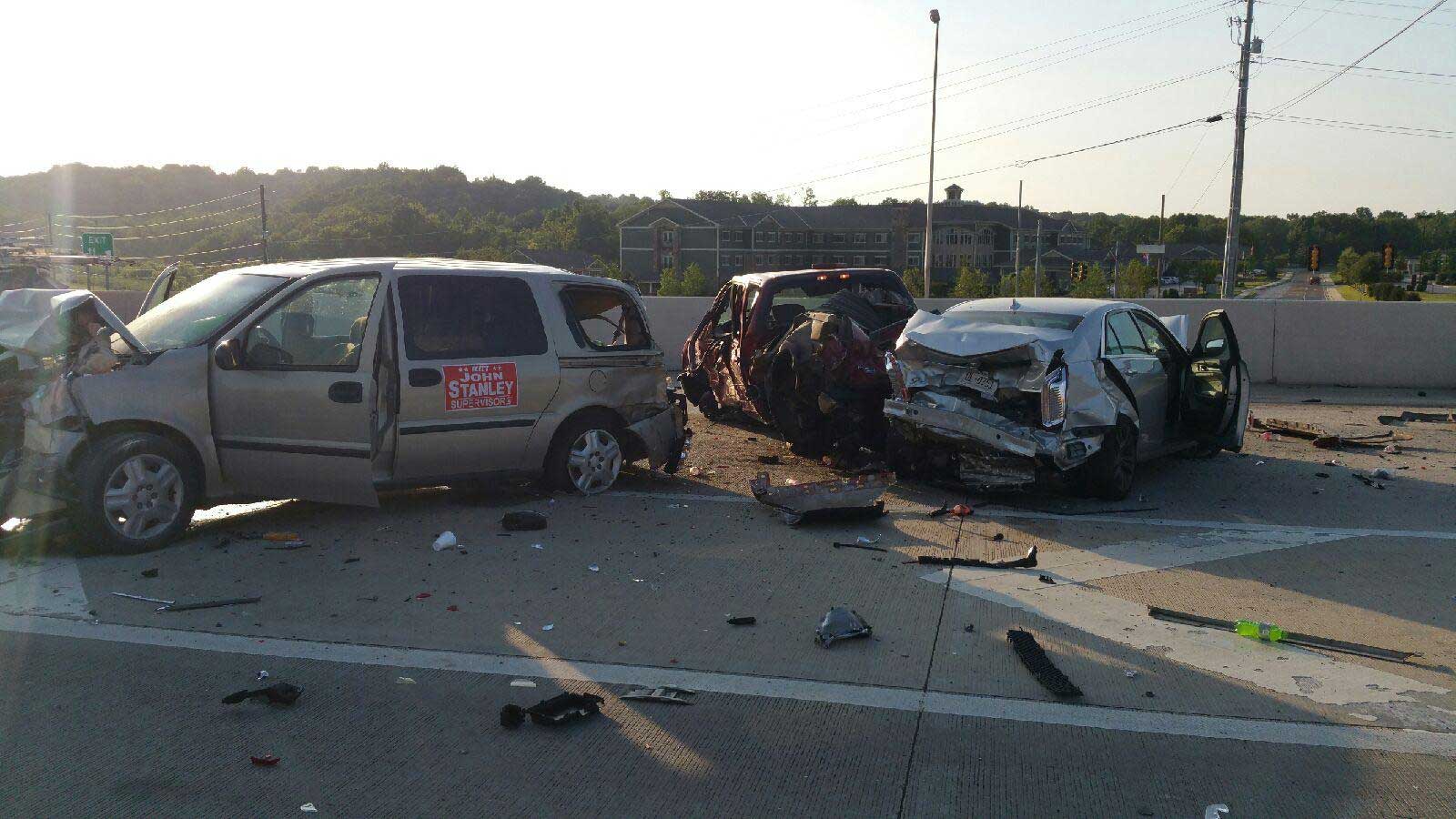

Six people died and six were injured in that June 25 crash, a crash that veteran officers later described as the most horrific they’d ever seen. The crash ignited an intense investigation from local and federal authorities about how it happened.

But how it happened is a complex mix of factors, factors that are present in almost every city and in almost every truck. A pressure to drive farther, faster. An aging, crowded interstate system. A growing need to move freight and a growing shortage of truck drivers.

Those factors routinely end in fatal crashes. In 2013, 289 people died in crashes with large trucks in Tennessee and Georgia alone. Over 10 years that rises to 3,405 deaths. Nationally, more than 48,000 people died in 10 years.

But in Chattanooga, all the factors that lead to fatal crashes are magnified.

Three major interstates run through the city, and more truck traffic passes through Chattanooga than any other metro area in the United States.

A national shortage of truck drivers is putting more inexperienced drivers behind the wheel, and those drivers must navigate a mess of congestion in Chattanooga, plus a complicated interstate system. Interstates here narrow from six to two lanes, climb Missionary Ridge, curve through downtown and wind around Moccasin Bend.

All it takes for a fatal trucking crash is one extra factor, like a careless driver, to tip the scales.

That’s what happened on June 25.

And the city is perfectly primed for it to happen again.

Stop at any trucking establishment in the rural interstate town of London, Ky., and somebody will know Ben Brewer’s name.

The 39-year-old Brewer drove trucks out of London for years, hauling for a local company called Hilltop Transportation.

Hilltop won’t comment on when or why Brewer left, but records show Brewer was hired at another, smaller London trucking company — Cool Runnings Express — on June 22. On that same day, Brewer started a run from London to Haines City, Fla., and back — the trip that ended tragically in Chattanooga on June 25.

A blue collar town of 8,000 people where the median income is $30,000, London is nestled against I-75 about 100 miles north of Knoxville in eastern Kentucky. It’s coal mining country — many pickup trucks are still adorned with pro-coal bumper stickers — and it’s the kind of place where GPS units lose signal and families have eaten at the same Main Street restaurant for 70 years.

Here, just off Exit 41, Chris Sanders manages the London Auto Truck Stop, which he boasts is “known far and wide for its good food and treating you like family.”

The truck stop is the largest in London, and it holds Cool Runnings’ fuel account.

“This is their main stop,” Sanders said.

Cool Runnings’ owner, Billy Sizemore, is respected in town, Sanders said. He and his wife are good people, Sanders said, honest, upstanding folk.

But on Ben Brewer, Sanders had little to say — and nothing good.

Cool Runnings Express is a small operation. Sizemore runs just three trucks. Including the wreck in Chattanooga, Cool Runnings has had two serious crashes during the last two years, according to the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration.

The company’s safety record is mixed. Of 19 random truck inspections during the last 24 months, inspectors found problems in 12 cases.

“It’s been bad news for us,” Sizemore said of Brewer’s wreck, “but for the families who lost their loved ones — we just hated to hear something like that.”

He declined to speak further with the Times Free Press, citing the three lawsuits filed against him after the wreck for a combined $33.5 million.

The day he was hired, Brewer passed a drug and alcohol test for Cool Runnings and hit the road. But he ran into trouble from the start.

His truck broke down as he picked up his load in Kentucky and he was forced to return to London for repairs. Mechanics fixed his air compressor — it had been unable to generate sufficient air supply to properly operate his brake system — then sent him on his way.

But shortly after leaving the repair shop, Brewer returned, complaining that the truck was behaving abnormally. This time, the shop employees fixed his fuel delivery system. After the second repair, Brewer finally began the trip to Florida.

He reached Florida on June 24 after being on-duty for about 45 consecutive hours — well beyond limits set by the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration.

Federal regulations only allow truck drivers to be on duty for a maximum of 14 consecutive hours. And of that 14-hour shift, drivers can be behind the wheel only for 11 hours before they must take a minimum 10-hour break, according to the federal agency.

The extra non-driving, on duty hours are often spent loading and unloading, when the driver is working but not actually driving.

About 75 miles away from his drop-off point in Florida on June 24, Brewer tried to pass a delivery truck in Wildwood, Fla., but instead sideswiped the vehicle, forcing both trucks off the road. Florida Highway Patrol officers determined that Brewer was at fault, wrote him a ticket for $166 and sent him on his way.

There wasn’t much else they could do. Federal regulations don’t require law enforcement officers to drug test truck drivers after a wreck — that’s the responsibility of the truck driver’s employer, and even employers are only required to test when a crash results in disabling damage and the truck must be towed away.

When two trucks crash on the side of a busy highway in the middle of the morning traffic rush, troopers just want to get the road cleared as quickly as possible.

“The trooper has to have some sort of probable cause to enforce anything else or go any further,” said Sgt. Steve Gaskins, spokesman for the Florida Highway Patrol. “There’s got to be slurred speech, or some sort of behavior that sets me off and tells me I need to dig deeper.”

Brewer repaired his truck himself on the side of the road — which took between three and four hours — then continued to his drop-off point in Haines City. By the time he arrived at 4:30 p.m. and logged himself as ‘off duty,’ he’d been working for 50 hours straight.

He took a 12-hour break, then got back behind the wheel for the 769-mile trip back to Kentucky. He faked his paper logbooks to make it look like he was following federal regulations.

And after 15 hours on the road, Brewer reached Chattanooga just after 7 p.m. on June 25.

A construction zone tapered traffic down to a crawl heading north on I-75 just past Ooltewah that night. Vehicles in the left lane were stopped all together, while the center and right lanes only inched along.

Caught in the slowdown, Brian Gallaher, a 37-year-old band teacher at Ocoee Middle School, drove a Prius, headed toward home, toward his wife and two children.

Jason Ramos, 36, the assistant director of residential life at Dalton State College, sat in his 2003 Mazda nearby.

And the Watts family filled the Toyota Scion. Savannah Garrigues, 9, sat in the back seat with her 11-year-old sister Kelsie. Tiffany drove and her mother, Sandra Anderson, 50, sat in the front passenger seat.

Tiffany called her husband at 7:06 p.m. and he didn’t answer.

And then from behind came Ben Brewer, going 77 miles per hour.

His truck slammed into Gallaher’s Prius first, then the Watts’ Scion, throwing Tiffany out of the car. The tractor-trailer hit Ramos’ Mazda, which lodged into the truck’s grill and was carried along as the truck smashed into two Ford pickups, two vans and a Cadillac.

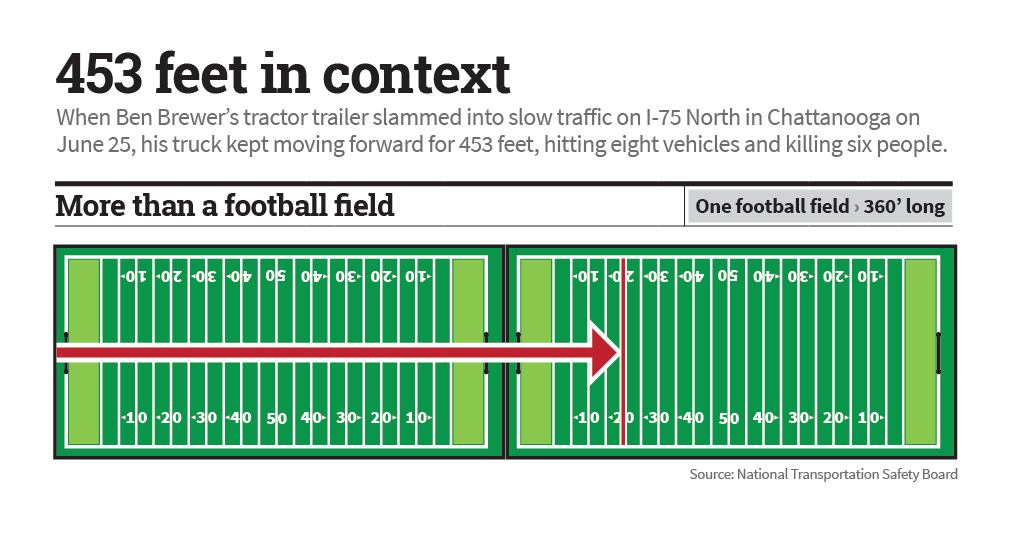

Brewer drove for 453 feet — longer than the length of a football field — before the truck finally came to a stop.

The Watts’ car burst into flames. Witnesses tried to pull the girls out, but the fire was too hot and too fast. The smell of gasoline and smoke filled the air. The nine-vehicle pileup shut down the interstate for hours and included 18 people — six dead, six injured and six unhurt.

The Hamilton County medical examiner would later conclude each of the six who died were killed by blunt force trauma, not the flames.

In an instant, the dedicated band teacher and the fun-loving college staffer were gone. The nursing student who’d practice her speeches in front of the chickens in the backyard was gone. The sisters who loved building forts, dancing and reading were gone. The grandmother who dished out sloppy, wet kisses was gone.

Ben Brewer walked away.

Chattanooga police took Brewer and his fiancee — who was riding in the truck with him during the crash — to the Police Services Center on Amnicola Highway for interviews. Brewer seemed a little off, investigators would say later, but everyone reacts differently to trauma. Police brought in a drug recognition expert to check his behavior.

And after the interviews, they let Brewer and Charity Pennington leave. Investigators still had reams of data and evidence to sift through and didn’t have enough evidence to charge Brewer for any crimes at that time.

They couldn’t hold him without charging him, so Brewer and Pennington went back to Kentucky.

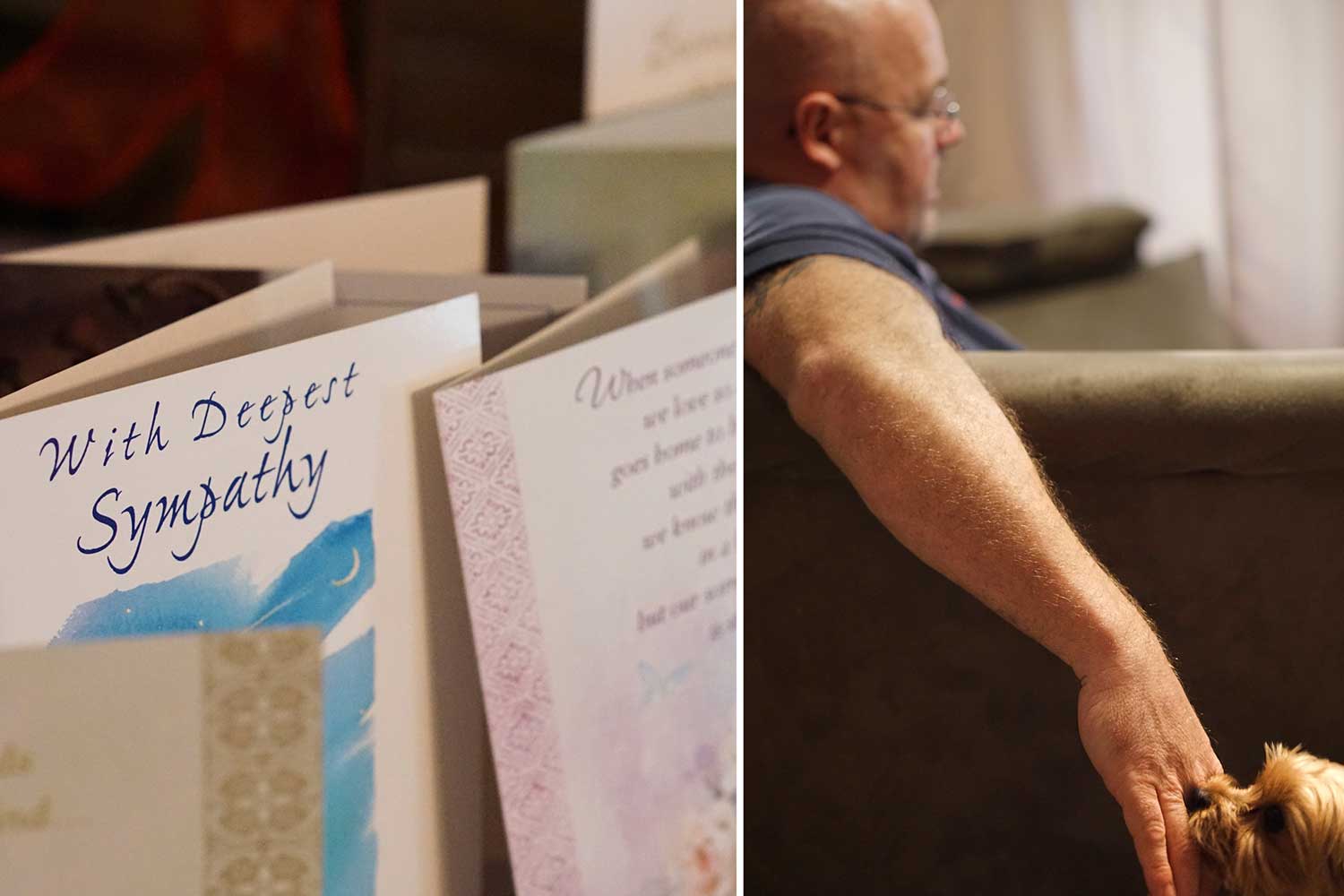

Families and friends of the victims began organizing vigils and funerals. Obituaries ran in newspapers. Well-wishers donated thousands of dollars to GoFundMe accounts for the families of the victims.

A private investigator showed up at Rick Watts’ home, encouraging him to sue. You should be mad as hell, he told Watts. I don’t know what happened yet, Watts told him, standing in the garden Tiffany loved. I’m still praying it was an accident. Accidents can happen.

Forty days later, a Hamilton County Grand Jury indicted Brewer on six counts of vehicular homicide, four counts of reckless aggravated assault, driving under the influence of narcotics, speeding and making false reports about his duty status. In addition to driving far longer than legally allowed, Brewer also tested positive for methamphetamine after the crash.

“This was no accident,” Watts said in October.

After the warrant for Brewer’s arrest, nobody could find Brewer for a week. Authorities in Kentucky searched his home and checked in with his family but came up empty. The Tennessee Bureau of Investigation added Brewer to its list of Top 10 Most Wanted Fugitives. After five days on the run, he was arrested in Lexington, Ky.

Lexington police found Brewer and Pennington in a vehicle outside a shopping center on Aug. 7. Pennington had $3,067 in cash in her purse, and Brewer had three grams of methamphetamine in a bag in his pocket, as well as half a bar of the prescription drug Xanax.

He kicked out a police cruiser window during the arrest.

Shortly after Brewer was caught, authorities in Lexington dropped local charges against him — charges related to the meth found during the arrest and the cruiser vandalism — and he was extradited to Chattanooga, where he is being held in the Hamilton County Jail. His case is just beginning to wind through the court system here.

Brewer keeps his head down and says as little as possible during his appearances.

And while Chattanooga police have handed their criminal investigation over to the district attorney, the National Transportation Safety Board is still investigating the crash. That investigation could easily stretch into 2016.

The federal safety agency doesn’t investigate every traffic accident. It only sends teams to accidents that have a broad implication — a wreck that is part of a trend or could spark nationwide changes. If a wreck meets that threshold, the NTSB typically sends five investigators.

They sent 11 to Chattanooga.

Chattanooga is a trucking town.

It’s not an identity that city leaders often herald — not like Volkswagen or the Riverwalk or the outdoor recreation scene — but the city’s trucking heritage is undeniable.

Covenant Transport and U.S. Xpress — two of the top 25 truckload carrier companies in the United States — are both headquartered in Chattanooga. Together, the companies put 9,700 trucks and 25,700 trailers on the nation’s roads and employ 1,700 people in Chattanooga. The companies — started by step-brothers David Parker and Max Fuller — are the descendants of long-haul pioneer Clyde Fuller’s company, Southwest Motor Freight.

Another younger Chattanooga trucking logistics company — a start-up formerly called Access America Transport — sold last year to Coyote Logistics for hundreds of millions of dollars, merging to create a powerhouse in the industry and making millionaires of Access America’s three Chattanooga founders. Coyote Logistics then sold to UPS for $1.8 billion in July 2015.

The city also sits at a major crossroads, at the intersection of three interstates — I-75, I-24 and I-59 — which makes it a key location for truckers with routes along the East Coast, for anyone running freight between the Canadian border and the Florida Keys.

But while the interstates drive much of Chattanooga’s trucking industry, they also set the stage for trouble on the region’s roads. The sheer number of trucks passing through Chattanooga on the way to somewhere else adds thousands of tiny moving parts to an already volatile scenario.

On average, more than 208,000 vehicles traveled Chattanooga’s three interstates each day in 2014, according to statistics kept by the Georgia and Tennessee departments of transportation.

CHATTANOOGA'S INTERSTATES - AVERAGE DAILY TRAFFIC COUNT, 2014

I-24 - 69,173 vehicles

I-59 - 21,500 vehicles

I-75 - 117,599 vehicles

Thrive 2055, a local, long-term planning group, found that 80 percent of trucks traveling through Chattanooga never stop in the city. That’s the highest amount of through truck traffic of all major metro areas in the United States.

And those truckers often arrive in Chattanooga in a bad state of mind, said Chuck Clowdis, managing director and transportation consultant with IHS Economics, an international industrial consultant firm.

“Once you get out of the congestion in Atlanta, you’re trying to make up some lost time, so you’re running just as fast as you can and as hard as you can in the left lane,” he said. “And then all of sudden you get into this congestion, starting in Dalton. And you’re frustrated.”

It’s not just I-75. Drivers coming into Chattanooga on I-24 out of Middle Tennessee are coming off Monteagle Mountain’s steep slopes, while drivers on the way up from Alabama and Georgia on I-59 are leaving a long, lonely stretch of mostly straight highway.

“You could absolutely mesmerize yourself as a truck driver from Birmingham to the [24-59] split, because there is nothing happening,” Clowdis said.

Conditions on the roads around Chattanooga amplify the pressure on trucks to quickly get through and around the city, meaning drivers are more likely to go too fast or pay too little attention as they pass through.

“These truckers are not looking for an exit,” said Clowdis. “They’re looking for a way through.”

Like Ben Brewer, some truckers who pass through Chattanooga are traveling I-75, which narrows from three to two lanes at Ooltewah and heads up a steep incline, cutting through White Oak Mountain and snarling traffic headed toward Cleveland and Knoxville.

That stretch of I-75 between Chattanooga and Cleveland is prone to accidents — there were 16 fatal truck-involved crashes there between 2003 and 2013, according to the most recent data available from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration.

“I’m not sure what to say, other than it’s [a] cannonball-run stretch through there; everyone wants to be first,” said Robyn Young, a truck driver from Cleveland, Tenn.

Chattanooga is due for infrastructure upgrades. Gov. Bill Haslam and TDOT Director John Schroer visited the city in November, stumping for road funding to fix problems like the I-75 and I-24 split, where the road narrows. But aging and crowded interstates are by no means exclusive to the city.

The nation’s sprawling interstate system — once the envy of the developed world and widely credited with making the U.S. a world economic power — is at every corner strained under its current burden.

When construction started on the interstate network in 1956, the population of the country was 169 million. Today, there are 320 million people in America. And there are more than 1 million trucking companies registered currently in the United States, with more than 3 million commercial drivers working for them.

Interstates that initially opened unprecedented lines of commerce across the country and sped the delivery of goods are now, in many areas, too small and unable to accommodate traffic.

Widening the interstates is a dream solution for many transportation experts and business leaders, but funding isn’t there to support it.

Federal highway funding shortfalls have loomed over the country for years, and as recently as the end of October, the Highway Trust Fund — which helps provide up to 50 percent of the nation’s funding for transportation — was in jeopardy. Congress has continually failed to agree on long-term solutions.

The situation angers Parker, president of Chattanooga-based Covenant Transportation Group and board member of the American Trucking Associations. He said commercial trucking firms are agreeable to paying higher diesel taxes to improve the interstates.

Carriers are reliant on free and easy movement around the country to make their money, and when that movement is restricted because of failing or overcrowded highways, it hits them in the wallet, he said.

“Now, our supply chain and load inventory are absolutely dependant upon an interstate system that works, and it doesn’t work,” Parker said.

T he fact that a resident of Chattanooga can order a sweater from Seattle on a Monday and wear that sweater to work on Thursday is a testament to the efficiency of the U.S. freight system.

Every year, 10 billion tons of goods roll across bridges, pass through tunnels, and criss-cross state lines. Trucks carry laptops, chairs, carpet, wires, books — Chattanooga’s homes and businesses are filled with goods hauled on trucks.

And those goods are inexpensive, all things considered.

They’re inexpensive because truckers can get goods where they need to be, and fast. Truck drivers like Robert Perez haul 44,000 pounds of limes from Texas to New York day in and day out, full-time, for years.

They’re inexpensive because large trucking companies are pushing out smaller companies, delivering goods safer and faster than one-man bands like Billy Sizemore and Ben Brewer who struggle to turn a profit and might be more likely to shirk safety regulations to stay afloat.

“The little guys are finding it harder and harder to exist,” Clowdis said. “The pressure on shippers to get the best bang for their buck is more intense than ever. It’s a good thing. I’m all for efficient supply chains and getting the best service for the right price. People need to eat. The freight will move.”

But that pressure, that efficiency, that only-moving-trucks-make-money reality pushes drivers to go farther, faster, longer. And it limits the ability of federal regulators to make the roads safer. If the trucks slow down, the cost of goods goes up. If the cost of goods goes up, consumers spend less. If consumers spend less, the economy falters.

“Every time someone in Washington says ‘This will stop it’ — it’s like train speed,” Clowdis said. “Someone will say, ‘I’m going to slow down all the trains.’ Well, yeah, you are, but you won’t have any fresh cabbage or fresh tomatoes coming out of Florida.”

But that hasn’t stopped federal regulators from trying. Congress created the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration in 1999 and tasked the new agency with preventing commercial vehicle-related accidents and injuries.

Federal officials first introduced new hours of service regulations in 2003, and have since tweaked the regulations several times. Parker and other industry leaders say the shifting federal regulations create confusion among drivers and make the job more difficult for trucking companies.

And the federal regulations haven’t done much to stymie the pace of fatal truck crashes — between 1982 and 2008, the number of people killed annually in crashes involving large trucks hovered at or near 5,000 each year, according to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration.

Trucking deaths hit a 31-year low in 2009 — dropping to 3,380 at the height of the recession, when fewer trucks were on the road — and have climbed every year since, reaching 3,964 in 2013, according to the latest annual data available from the NHTSA.

The numbers show that the consumer drives the trucking industry. The need for goods — inexpensive, fast, goods — keeps truckers on the road.

But the modern convenience of fast and inexpensive delivery comes with sacrifice and compromise. Something has to give. Some piece of the system has to bow out, take a back seat, make way for the burning efficiency of the supply chain.

Right now, the compromise is safety.

And the sacrifice is lives.

“I look at trucks like a cocked gun,” Watts said. “They are ready to strike.”

He spent the morning of June 25 cleaning out the backyard pool so it’d be ready for the girls when they got in from the airport. Savannah and Kelsie used to be afraid of the water, but they’d both grown to love the pool, the splashing summertime tradition.

The pool was ready by the time Watts left for work that day.

But no one ever came home.