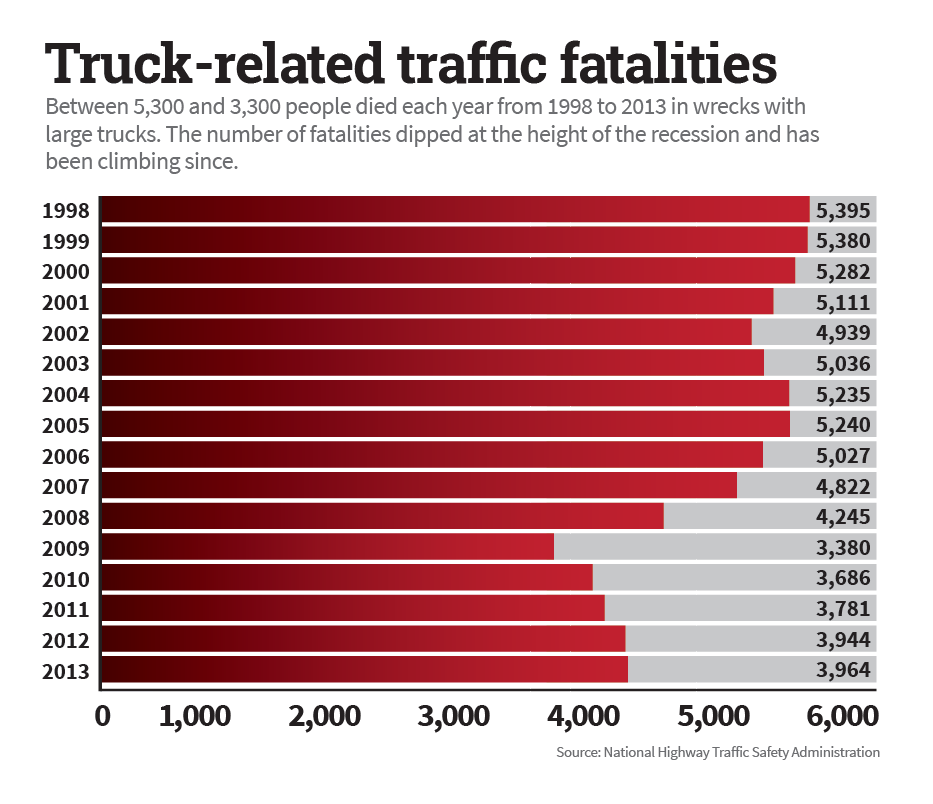

he men, women and children killed in wrecks with trucks between 1982 and 2013 would fill Neyland Stadium one-and-a-half times.

In that 31-year span, 159,220 people were killed in accidents with large trucks in the United States, according to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration.

Lawmakers and trucking experts have been trying to solve the problem of trucking-related deaths for years. But while the problem is obvious, no one can agree on how to stop the death toll from rising.

Traffic fatalities can be reduced, experts argue, with fixes that range from repairing and expanding the interstate system to installing technology that makes trucks safer to transporting more goods by rail. But the solutions can be costly, politically unpopular and inconvenient.

The best long-term solution — overhauling the nation’s roads and upgrading the infrastructure — is also the most unlikely.

Tennessee sports a backlog of $6 billion in transportation projects, and while Gov. Bill Haslam has repeatedly called for more transportation funding, state lawmakers have consistently pushed back against the prospect of raising taxes to pay for the repairs.

The last time lawmakers increased the state gas tax was in 1989, to 21.4 cents per gallon from 16 cents. That generates about $657 million for the state’s highway fund, which transportation experts agree is not enough. The state’s gas tax rate would have to be 38 cents per gallon today to have the same purchasing power as 20 cents per gallon in 1989.

“At some point, you’re going to have to address bringing in more revenue,” Haslam told reporters in October. “The path we’re on now will not work.”

Higher road maintenance costs and the rise of vehicles that use less fuel or alternative fuels have also contributed to the road funding shortfall, according to the Tennessee Comptroller of the Treasury’s office.

In Georgia, lawmakers upped the per-gallon gas tax to 26 cents in April from about 19.5 cents, a move that the state expects will generate $700 million to be used for transportation. Other increases in taxes and fees in April added another $200 million to the pot.

But even that $900 million falls short of what the state will need.

A state committee studied Georgia’s transportation network and concluded that the state needs to increase transportation funding by $1 billion to $1.5 billion — nearly doubling the Georgia Department of Transportation’s $2 billion budget.

And at the federal level, the transportation funding picture is just as bleak.

Congress had a chance to craft a long-term budget solution for infrastructure earlier this year, but instead waited until days before the Oct. 29 deadline to keep resources flowing to the nation’s roads. And when Congress did act, the solution lawmakers agreed on was short term.

Legislators passed a six-year, $325 billion funding bill in July — but the federal Highway Trust Fund still faces a $30 billion shortfall that must be addressed within the next three years if Congress’ six-year plan is to be carried out.

And in early December, Congress passed a separate transportation bill that will increase highway spending by 15 percent and transit spending by 18 percent over five years. The $281 billion allotted by the bill is subject to annual spending decisions by Congress, rather than being paid for from the federal Highway Trust Fund, according to The Associated Press.

And it still falls about $200 billion short of what top transportation officials say is needed.

Sen. Bob Corker, R-Tenn., has been one of the loudest proponents for transportation funding, and he recently championed a 12-cent federal gas tax hike that failed to gain traction. The former Chattanooga mayor has been critical of Congress’ tendency to make short-term fixes by borrowing funds and shoring up deficits in the Highway Trust Fund as they arise, rather than proactively developing new sources of income.

“Congress — both Republicans and Democrats — should be embarrassed that it has allowed the Highway Trust Fund to become one of the largest budgeting failures in the federal government,” he said. “I believe we have three options. We can spend less on these programs. We can devolve the highway program back to the states. Or we can collect enough user fees to sustain the trust fund. I am open to all of those options, but what I cannot do is participate in abject generational theft where we are stealing from our children’s futures to pay for today’s priorities.”

Corker proposed raising gas taxes by 6 cents per gallon two years in a row, which he claimed would fund the Highway Trust Fund for a decade.

Congress rejected the proposal. Opponents said the Highway Trust Fund hands out too much money to non-interstate infrastructure, and members of Corker’s own party refused to back him. U.S. Rep. Scott DesJarlais maintains that reallocating funding is the answer, not raising taxes.

“With billions of dollars in waste, fraud and abuse contained within the federal budget, there is absolutely no reason we can’t eliminate frivolous federal programs to help ensure our infrastructure needs are met,” he said.

Leaders at Thrive 2055, a group that is focused on long-term planning in the Chattanooga region, aren’t counting on federal funding as they plan for the region’s transportation needs 40 years from now, said senior project manager Bridgett Massengill.

“What is the one trend that we all know without a doubt is coming toward us in transportation?” she asked. “Deteriorating federal funding.”

Even if the money were available, Chattanooga’s geography makes widening the roads especially problematic, said Thrive 2055’s communications manager, Ruth Thompson.

“It’s much more difficult to expand an interstate along a mountain versus a prairie,” she said.

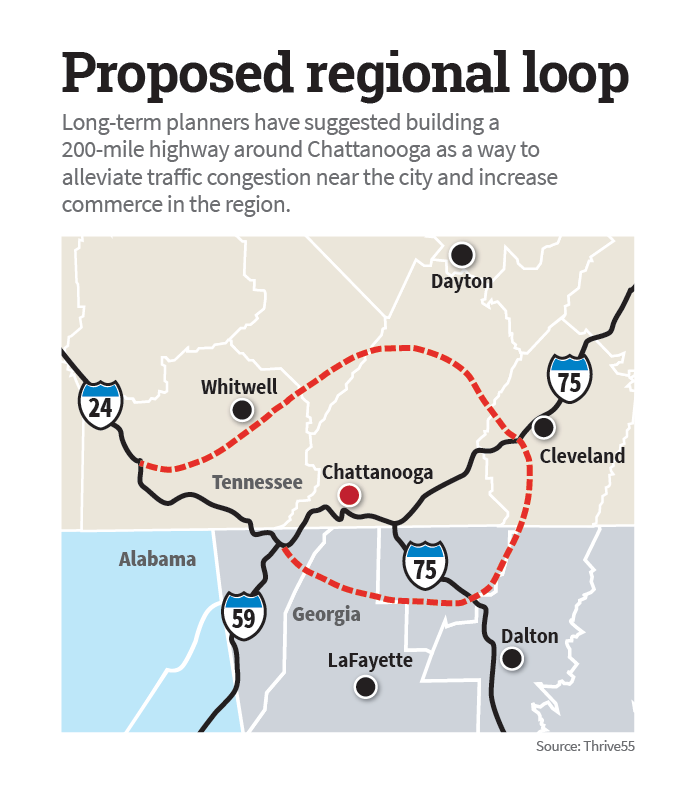

Thrive 2055 has suggested building a 200-mile loop road around Chattanooga as a way to help alleviate anticipated increases in traffic and congestion. But such loops can easily take years to build, and cost in the hundreds of millions of dollars — the southern half of Nashville’s outer belt, for example, took 26 years to build and cost $763 million.

In Boston, the infamous Big Dig project, which rerouted interstate traffic through a new underground tunnel, took 16 years and $24 billion to complete. It was the most expensive highway project in U.S. history.

S

afety advocates say groundbreaking technology could be the answer to the problem of truck-related traffic fatalities — these days, trucks can be outfitted devices that sound the alarm whenever a truck driver drifts between lanes, and those devices can even send alerts to a trucker’s home terminal to warn fleet managers that the driver might be fatigued. Other new gadgets can slam on a truck’s brakes to avoid a collision, or shut down the engine if a driver exceeds his hours of service.

But the technologies are imperfect and expensive.

Many large fleets — like Covenant and U.S. Xpress — are happy to spring for safety mechanisms on their trucks, because each device lessens the risk that drivers will cause crashes and open the companies up to costly lawsuits. Smaller trucking companies work on tighter margins and usually can’t afford to invest in optional equipment.

The federal government requires drivers to keep a log of their hours of service each day — recording when drivers are on the road, unloading, loading, stopping for breaks, sleeping — and for decades drivers kept those records with pen and paper, manually marking each change in a logbook.

But electronic logs — which record those changes automatically, in a way that the driver can’t tamper with — are gaining ground. On Dec. 10, the federal government ruled that all large commercial trucks in the country must switch to electronic logs within the next two years, and estimated that the rule change will save 26 lives each year.

Both Covenant and U.S. Xpress already use electronic logs in all of their trucks, and hope the new federal mandate will force smaller companies to do the same, preventing any driver from driving too long and faking the log book to cover it up.

Covenant has also installed lane-departure systems in some of the company’s trucks. Cameras and computers monitor the lines on the road, and if the lines disappear, the cabin speakers buzz to warn the driver. If the lane departure system is activated too many times, it automatically sends alerts to a truck’s home terminal to warn fleet managers the driver might be sleepy.

But the systems haven’t yet been refined, and can be glitchy — sounding the alarm when the white line disappears in construction zones or on exit ramps when the truck is well within its lane.

Anti-collision devices are also an emerging technology. The systems are designed to automatically apply the brakes to keep a truck from rear-ending slow-moving traffic ahead. Such from-behind-crashes are often the most deadly, and often happen inside highway construction zones.

Truck driver Ben Brewer crashed into stopped and slow-moving traffic in a construction zone on Interstate 75 in Chattanooga on June 25 and killed six people. In April, a tractor-trailer slammed into slow-moving traffic outside Savannah, Ga., killing five nursing students.

And in June 2014, a Wal-Mart tractor-trailer crashed into stopped traffic in a construction zone in New Jersey, seriously injuring comedian Tracy Morgan and killing another man. Nationally, one in four fatal crashes in construction zones involve heavy trucks, according to the U.S. Department of Transportation.

The truck that hit Tracy Morgan actually was equipped with anti-collision technology, but it didn’t work. Federal investigators were unable to pinpoint the reason why, but most anti-collision systems work best when the traffic ahead is moving at least slightly.

The systems don’t typically hit the brakes when a truck approaches a completely stationary object, because the devices aren’t sophisticated enough to determine whether that stationary object is a bridge or a vehicle or a guardrail.

And a truck coming to a sudden halt in the middle of the interstate because the anti-collision system thought a bridge was a car is just as dangerous as a truck speeding into traffic from behind, said Rick Reinoehl, senior vice president of risk management at Covenant Transport.

S

ince an infrastructure overhaul is unlikely and on-board safety technology is imperfect, Thrive 2055 and other long-term planners point to more immediate solutions, like diversifying the way freight is transported.

One way to reduce trucking fatalities is to have fewer trucks on the road — and one way to do that is to shift some of the freight burden into other modes of transportation: water, air and rail.

Right now, nearly 70 percent of all freight in the U.S. moves in trucks, according to the American Trucking Associations. About 13 percent travels by rail and 11 percent through pipelines. Only 6 percent of the nation’s freight moves by air.

Currently, about 1.3 percent of freight is intermodal, meaning it travels by both rail and truck, often arriving on the coast in a shipping container, then going by rail to an inland port before being picked up and delivered to its final destination by a tractor-trailer.

The idea is to move freight from California to Georgia on a train, instead of the back of a truck, reducing the number of long-haul truckers on the interstates. Proponents argue that the country already has a vast railroad network and that transportation leaders should learn to better utilize it.

Such intermodal freight is on the rise, according to the American Trucking Associations. The trade association expects intermodal freight to increase about 5 percent each year between 2017 and 2021.

In July, Georgia officials announced the creation of a new $24 million inland port to be built in Chatsworth, Ga., about 50 miles south of Chattanooga.

Deemed the Appalachian Regional Port on U.S. 411, the inland port is designed specifically for intermodal freight. Truckers will bring freight into the port, then the containers will be loaded on to freight trains for the 388-mile trip to the Port of Savannah.

The inland port is expected to take 50,000 trucks off the roads, officials said.

But transportation diversity isn’t a one-sided deal. Reducing the number of total vehicles on the roads — not just trucks — can also help curb fatal crashes, and many safety experts are pushing for increased public transportation.

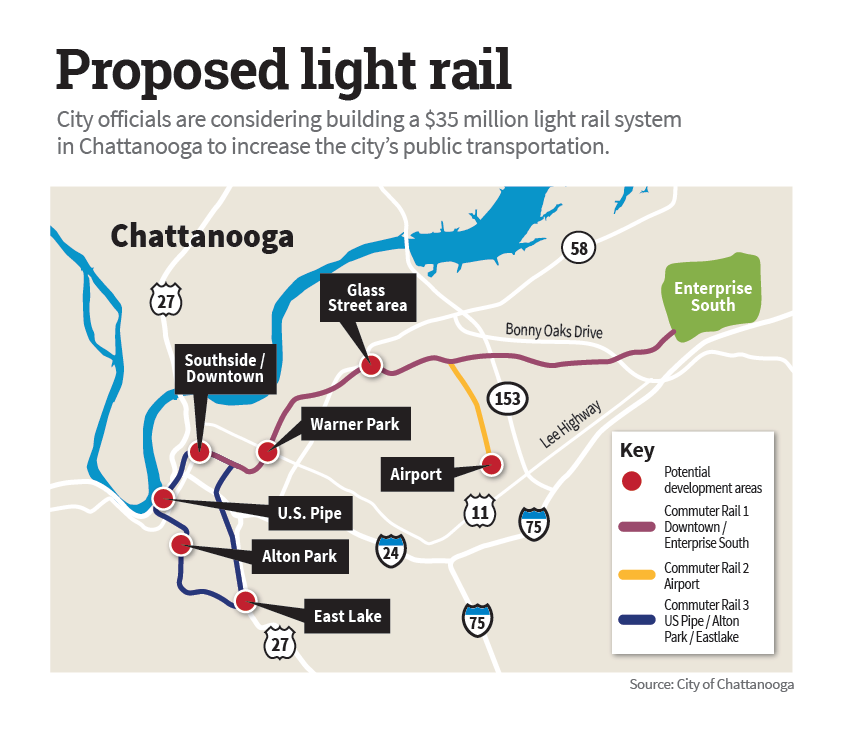

Chattanooga is spending $300,000 — plus a $400,000 federal grant — to study the feasibility of a proposed light rail system that would crisscross the city, stretching from Enterprise South to East Lake.

The system is estimated to cost at least $35 million, but some experts believe that estimate is too low. A 32-mile, nine-station light rail system in Austin, Texas, was completed in 2010 for $100 million.

City officials have pushed the light rail system as a way to provide better inner-city transportation and bring economic development to depressed areas of the city, but the system could also lighten the load on Chattanooga’s roads.

Too many locals use Chattanooga’s interstates for short, local trips, said Massengill. The region’s state and local highways aren’t traveled as much as they used to be — or as much as they could be.

“We need to raise the bar of visibility on some of those alternative routes,” she said.

It’s a move that truckers can’t make — their big trucks struggle to navigate small back roads. So the responsibility falls on local drivers, Massengill said, to free up space on the interstates and make them safer for everyone.

Massengill said the only way to solve the problem is for the trucking industry, lawmakers and car drivers to work together.

“That man, what he did was a criminal act,” she said of Brewer. “I don’t want to see us turn against the trucking industry as a result of a criminal.”

“What we need to look at is the bigger issue of how to grow and how to handle the growth that is coming our way,” she said, “in a way that would make our region prosper and not be held back by a criminal’s act.”