THE WITNESS PROBLEM

SPEAK NO EVIL PART 2

BY TODD SOUTH

PHOTOGRAPHY BY DOUG STRICKLAND

IN THIS CITY IT’S NOT HARD TO SHOOT A PERSON,

EVEN KILL SOMEONE, AND GET AWAY WITH IT.

JUST CONSIDER LONTA BURRESS JR.

Nearly four years ago, the 16-year-old gang member fired into a crowd at Coolidge Park, injuring five people. Later that year, he drove a stolen pickup truck while his friend in the passenger seat peppered a school bus with bullets. Seven months later, he shot and killed a childhood friend while six people watched.

If witness testimony had been stronger, each time might have been the last time. But at each turn, a witness balked. One recanted his story. Another said she didn’t remember. The last testified at an early hearing but swore he wouldn’t come back for the trial.

Since 2011, nearly 300 people have been shot or killed in Chattanooga. A Times Free Press investigation found that in more than half of the shootings, no arrest has been made. Twelve of the cases were dismissed. So far, fewer than two dozen people have been sentenced to prison time.

In more than half the total cases, police and prosecutors say, the problem is a lack of willing and credible witnesses.

“It can be frustrating because people’s stories change … or you think something happened but you can’t prove it, so we can’t go forward,” said Neal Pinkston, the second-in-command at the Hamilton County District Attorney’s Office.

Talk to people in the inner city and to the families of the victims, and they’ll say that witnesses won’t talk because doing so is dangerous and futile. When shooters get away, they return to the neighborhoods more brazen than before. The Times Free Press analysis shows that is true.

Source: Based on a Chattanooga Times Free Press investigation of police and court records

BREAKDOWN OF 300 SHOOTINGS

IN CHATTANOOGA SINCE 2011

MOST PEOPLE CHARGED IN LOCAL SHOOTINGS HAD FACED CHARGES

BEFORE, SOMETIMES FOR VIOLENT CRIMES LIKE MURDER AND

AGGRAVATED ASSAULT. BUT TIME AFTER TIME, WITNESSES

WOULDN’T TESTIFY, AND CHARGES WERE DROPPED.

SO JUSTICE LOOKS MORE LIKE THIS:

DEVANTE STOUDEMIRE

REGINALD OAKLEY

REGINALD MADDOX

Devante Stoudemire was 17 when first charged with shooting another person in 2010. But the victim refused to testify in Juvenile Court, and the charge was dropped. Months later he was arrested in the shooting death of JerMichael Richardson. He was put on house arrest awaiting trial. Two years later, while awaiting trial, prosecutors charged him in the killing of Steven Mosley. But after a key witness in the first shooting died and another refused to talk, the Richardson murder charge was dismissed. Stoudemire still faces a murder charge in Mosley’s death.

Police arrested Reginald Oakley, 36, on charges he shot up a public housing area with an assault rifle in 2011. But witnesses refused to come to court, and the three attempted-murder charges were dismissed. He was charged again with attempted first-degree murder in July 2012 for a separate shooting, but those charges also were dismissed. Oakley had been indicted on a first-degree murder charge in 1996 and pleaded guilty to voluntary manslaughter.

On the night of April 5, 2011, Reginald Maddox told police he was inside the Okie Dokie Mart at 1900 Roanoke Ave. and saw Tyrone Carmichael, 22, shoot and kill Cordarrius Armor. A year later, prosecutors had to drop charges against Carmichael when Maddox said he was drunk during the shooting and wouldn’t or couldn’t testify.

IT’S NEARLY IMPOSSIBLE TO CONVICT —

OR EVEN PRESS CHARGES — WITHOUT A WITNESS.

A PARK SHOOTING

On paper, Burress looks typical of many street-level shooting suspects. He was a juvenile runaway raised partly by his grandmother, with a father who was in and out of jail.

He twice brought a gun to Brainerd High School, and in his sophomore year he was expelled.

The same year, on March 27, 2010, he made the news after police said he brought a gun to Coolidge Park, a popular spot where children run around in fountains and moms push strollers on sunny days. Hundreds of teens gathered that evening, drawn by a barrage of text messages.

But the scene turned chaotic when bullets flew into a crowd. Five people were wounded.

That’s when Lebron Dejuan Upshaw, an 18-year-old who lived with his aunt, became the first of many would-be witnesses to back away from the chance to help put Burress in jail. Upshaw told police shortly after the panicked crowd scattered that Burress, 16 at the time, fired the gun. Two other men, 18-year-olds Taurean Patillo and Anthony Frieson, fled with Burress.

All three — Burress, Patillo and Frieson — were jailed for the shooting. A victim identified Patillo and Frieson to police. They also talked and gave enough information to make the charges against them stick.

Four months later, Upshaw changed his story. He said he couldn’t say Burress was the shooter. With no physical evidence and the sole witness recanting his testimony, Burress’s charges were dropped.

Upshaw was charged with making a false statement to police and aggravated perjury and served probation. He declined to talk to the Times Free Press.

When asked by a reporter three years later why Upshaw had changed his story, his aunt, Jowan Upshaw, said that she didn’t want to talk about it. She said she didn’t trust the police.

LONTA BURRESS JR. IS A PRIME EXAMPLE.

KEEPING IN TOUCH

Assistant Victim Witness Coordinator Emily Hale

A year later, Emily Hale tried to convince a witness to testify against Burress in another shooting.

The one witness she had to work with was a 16-year-old boy. His address changed, his phone number changed. When he turned 18 before the scheduled trial, he moved out of his mother’s house.

Hale called. And called. And called.

She is one of three women who shepherd cases as victim and witness coordinators for the Hamilton County district attorney. She writes, phones, counsels, cajoles and sometimes pressures witnesses to come to court.

Hale knows if she can meet a witness the first time they come into court, usually days after the shooting, she’ll be able to connect. That meeting plants her smiling face in the mind of the witness.

Along the way, Hale shuffles through stacks of pending cases heading to trial. She calls victims, family members, witnesses, police officers, evidence handlers and experts to ensure they’ll be at court when needed.

Notices and subpoenas are mailed out or hand-delivered by sheriff’s deputies. More than half come back undeliverable or marked with the wrong address. Hale then calls relatives and workplaces searching for a new phone number. She scours Google and Facebook.

Sometimes they’re blunt and say they don’t want to come to court or they’re scared. But often the clue is in the tone of their voice. It fades from confident to shaky. They’ve testified before, in the preliminary hearing. They don’t see why they have to come back.

“And you try to explain to them … you’re a key part of this,” she said.

If a trial finally comes, and the word guilty passes from the lips of the jury foreman, she smiles inside. When mothers of shooting victims cry at an acquittal, she cries.

A MOTHER'S LOSS

KIMBERLY WALKER, ERICKA HOLMES, AND LARONDA TOWNSEND EACH LOST A SON TO GUN VIOLENCE.

AND ALL THREE ARE WAITING FOR THE TRUTH ABOUT THEIR SONS' DEATHS TO SURFACE.

THE SCHOOL BUS

-

Lonta Burress Jr.

and Darius Gustus

Lonta Burress Jr. and Darius Gustus turn to watch the first witness approach the stand during the opening of the 2012 school bus stop shooting trial.

Photo by Jake Daniels

A few weeks before Christmas 2010, in the same year as the Coolidge Park shooting, Burress drove a friend, Darius Gustus, in a stolen pickup truck.

They pulled up to a school bus stop in Eastdale as the bus was unloading students from Brainerd High School. Gustus fired a gun four times at the students.

Police pursued the truck as Burress sped through intersections. Near the intersection of North Willow Street and Garfield Avenue, he hit another car and veered into a utility pole. The truck rolled.

Burress ran from the truck, along with Gustus and the girl sitting between them, Lajuana Detrice Woods, 17.

Woods later told police that Burress drove and Gustus shot. Police had an eyewitness.

But because Burress was still a juvenile and had no violent felony convictions, his bond was set at $30,000 and he was free by March.

Woods testified in Hamilton County Juvenile Court. But when she took the stand again a year and a half after the shooting, she said she couldn’t remember even being in the truck with her two friends.

The prosecutor made her read the Juvenile Court transcript of her testimony to a jury. Line by line, he questioned her about what she’d said before. Dozens of times she said she didn’t remember or couldn’t recall.

“Do you remember being in a red pickup truck at any point in time?” prosecutor Bret Alexander asked.

“I don’t recall. I don’t remember,” Woods replied.

The judge warned Woods not to lie. He said she could go to jail if she was dishonest. “And I don’t think you’re telling the truth.”

Without the transcript of Woods’ original testimony, prosecutors might not have won a conviction and six years apiece for Burress and Gustus. Though both would be parole eligible in less than two years.

But that conviction came too late for Darrius Townsend.

A POTENTIAL WITNESS

THE KILLING

Townsend grew up with Burress. The neighborhood called him “Dee with the Mole” because he had a brown mole on his upper lip. He was 17 and had a 3-year-old son.

Shortly after midnight on June 1, 2011, Burress headed to the cul-de-sac at 900 Taylor St. in Avondale. It’s where people cut through the Woodlawns, a cluster of government-subsidized housing, to a food mart or a liquor store about a block away.

There were rumors that Townsend owed Burress drug money. Some said Townsend had robbed someone with one of Burress’ relatives and maybe talked to police to get his charge dismissed.

A member of Burress’ street gang, the Crips-affiliated Rollin’ 60s, handed Burress a gun. Burress asked him if he could use it on Townsend, who was standing in the cul-de-sac, alone. The older gang member told Burress it was up to him, according to court testimony.

Burress walked down a slight hill to where Townsend stood. Six people were standing in the darkness a few hundred feet away, including 16-year-old Desmond Pittman, also a Rollin’ 60s member.

The teen turned away to walk up the hill when he heard a gunshot.

Pittman ran back down the hill and saw Townsend on the ground, on his back with his hands up pleading with Burress.

“Don’t do me like this, cuz,” Townsend said.

Of the six people there that night, none would come forward.

Days later, at the Riverbend Festival, police arrested Pittman for possession of a gun.

At first he wouldn’t talk. But a weapons charge would threaten his promising future in football. His mom worried. So he agreed to testify, and Burress was arrested again.

On the witness stand, Pittman covered his face with his hands, and then he scanned the courtroom. His eyes avoided Burress, seated directly in front of him, in chains and a jail jumpsuit.

“Have you been threatened not to come here?” the prosecutor asked.

“Sometimes … yeah,” Pittman replied.

“All right, who threatened you?” the prosecutor asked.

Pittman paused. The courtroom was silent.

“Rollin’ 60s,” Pittman said.

Defense attorney Kevin Loper asked Pittman why he didn’t talk to police initially.

“Because he capable of doing that, he capable of doing that to me, too,” Pittman said.

General Sessions Court Judge Bob Moon, now deceased, asked the prosecutor if there was anything similar to federal witness protection in the state system. The prosecutor said there was not.

“Then the gangs problem in Hamilton County will never be solved,” Moon replied.

“Mr. Burress will remain on a $1 million bond,” he said.

A poster shows Darrius Townsend, who was shot and killed in 2011. It was on display during a block party hosted by MASK, or Mothers Against Senseless Killings, held to remember those killed in street violence. The group was started by LaRonda Townsend, Darrius's mother.

Burress looked at him and pulled the trigger.

-

Desmond Pittman

A reluctant eye-witness, Desmond Pittman-Ross, testifies during Lonta Burress Jr.'s preliminary hearing in Hamilton County General Sessions Court.

Photo by Dan Henry

Darrius Townsend's mother, Laronda Townsend, washes dishes in preparation for a block party hosted by MASK, or Mothers Against Senseless Killings, which she started after her son was killed in a shooting in 2011.

WITNESSES FROM CRIME TO TRIAL

Until the trial begins, a witness can

return to the process at any time

The graphic below shows the many ways in which a witness in a criminal case can exit the process before a case reaches trial. While attorneys have subpoena power to compel a witness to come to court, that can antagonize an already reluctant witness or simply be ineffective if a witness doesn't respond.

PROSECUTION VS. DEFENSE

Even after hundreds of cases, prosecutor Cameron Williams shows passion in the courtroom.

When he unfolds his case for the jury, his voice rises and falls, his arms gesture wide, his eyes flash incredulously at claims of innocence.

He was one of two prosecutors on the school bus shooting, and he prosecuted Burress’ murder case.

He had Pittman’s testimony in the preliminary hearing, but not much else.

He deployed investigators to get more witnesses. They looked for the gun used to kill Townsend. Nothing.

They tried to get more people they suspected saw the killing to come forward, to talk. Silence.

Williams reviewed the file repeatedly, as the stack of cases on his desk grew ever higher.

IF A WITNESS MAKES IT TO COURT, HE HAS TO FACE AN ATTORNEY LIKE BILL SPEEK.

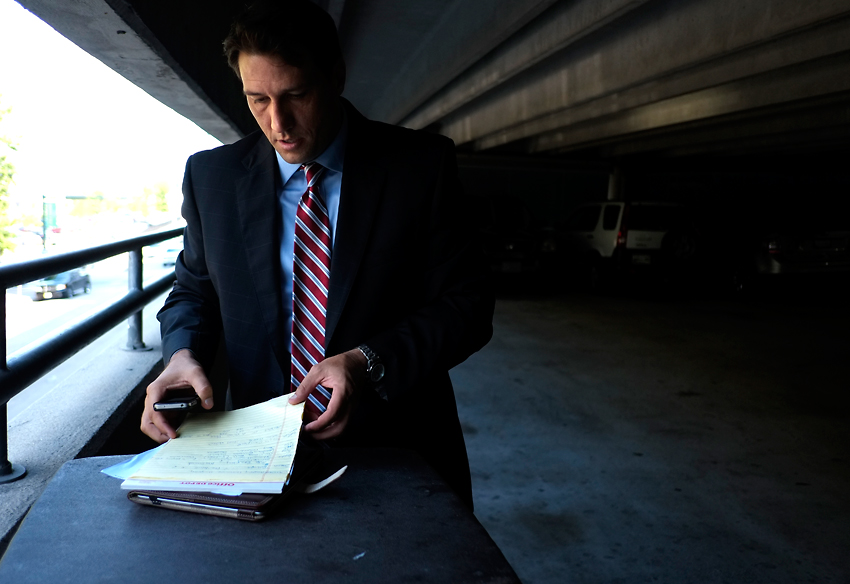

At 43, Speek still carries the swagger of the college baseball player and former pro-am volleyball player of his pre-lawyer life. On a typical day in Hamilton County Court, he races from one courtroom to the next. Between hearings, he’ll step into the parking garage for a cigarette, keeping him going after his morning Monster energy drink.

He doesn’t ask his clients if they did it, because he doesn’t want to know.

He knows witnesses can often be the prosecution’s weakness.

“Sometimes witnesses don’t come forward because they’re scared. Sometimes witnesses don’t come forward because they’re dirty. Sometimes witnesses come forward and they lie,” Speek said.

If the witnesses are questionable, he’ll shred their credibility, their memory, their motive for testifying.

“Reluctant witnesses are extremely susceptible to changing their stories,” Speek said.

Once the Burress family hired him, he soon learned prosecutors didn’t have much.

THE OUTCOME

After preparing for trial at least three times over the course of a year, Speek and Williams reached a deal.

Williams knew that with no physical evidence and a reluctant witness, he had a weak case.

Pittman hadn’t been back to court since he’d testified two years ago.

He told a Times Free Press reporter in July that he would not testify again. The victim’s mother, Laronda Townsend, pushed for a trial. She wanted more. Williams had to tell her he didn’t have anything more.

If Williams went to trial and lost, which was likely, Burress would have been freed once he finished his first sentence in the school bus shooting.

A plea would mean at least some accountability.

On Oct. 17, 2013, Burress pleaded guilty to voluntary manslaughter in a “best-interest” plea. In the legal world, that means he admitted a jury could convict him at trial but not that he did the crime.

After the hearing, Speek told the media that his client was innocent but knew he faced a gamble by taking it to trial. By taking the plea, he avoided a possible life sentence.

For pleading, Burress got five years, which was one year less than for his role as a driver in the school bus shooting.

But he was eligible for parole once he pleaded, based on time served and jail credits.

His parole hearing is in February.

-

Laronda Townsend

Laronda Townsend, mother of the late Darrius Townsend, becomes emotional during Lonta Burress Jr.'s preliminary hearing

Photo by Dan Henry

FIVE MONTHS AFTER

PLEADING GUILTY

TO VOLUNTARY

MANSLAUGHTER,

BURRESS COULD BE FREE.