SHONDA MASON WANTS TO KNOW

WHAT HAPPENED THE NIGHT

HER SON WAS MURDERED.

SOMEONE KNOWS THE TRUTH.

BUT THERE IS A CODE, AND SHE’S

NOT SURE IT CAN BE BROKEN.

SPEAK NO

EVIL

BY JOAN GARRETT MCCLANE

PHOTOGRAPHY BY DOUG STRICKLAND

HER SON’S BODY WAS LEFT SPLAYED ON A ROAD WHERE THE STREETLIGHTS WERE BROKEN.

If anyone knew why, they weren’t telling.

So Shonda Mason picked through the weeds that climbed over the jagged asphalt. She searched the leafy overgrowth swallowing a fence. She ran fingers over dirt to find the cave of a bullet hole.

She knelt to study the stains on the street.

Bushes revealed nothing.

The blood had washed away.

Rap. Rap. Rap.

She pounded on the back door of one of the houses that butt against the street.

Rap. Rap. Rap.

She imagined eyes behind the peephole, someone peeling blinds apart to see her face. No answer.

A woman drove up next door, and Shonda ran to the car.

“We was trying to find the spot where my son got killed,” she said, leaning in through the stranger’s window.

“He was laying in the street,” the driver said. That was all she would say.

Five months after Shonda’s 18-year-old son was found dead, his murder remained unsolved. His file sat within a stack of cases of other dead black teenagers, cases without evidence because witnesses wouldn’t talk.

Shonda knew that someone in the neighborhood had seen or heard about what happened that night. She understood why they wouldn’t speak about it. There was a code here. Before Eric was gone, Shonda had followed the code, too.

The code was never memorized or recited. It seeped into her from grade school.

“There are boundaries you don’t cross,” she said.

When someone kills your own, you kill them. You don’t rely on police sirens. You don’t tell what you saw. You handle it.

When Eric was 15, Shonda sent him to the hospital with a bullet in his stomach to get stitched up, belly button to chest. She taught him to ignore court subpoenas, to keep his name off court documents and police investigations, to say I don’t remember and I don’t know and I didn’t see anything.

The juvenile who police say shot Eric that time went on to be charged with killing two people. Eric never said a word.

Shonda sold crack cocaine her entire adult life, but he never told.

When a 17-year-old Eric was in a shootout, the police knocked on her door and she told the officers he wasn’t there.

She bailed him out on other charges. She followed the code.

Then Eric was dead, and all her black-and-white thinking turned gray. She’s been calling police and visiting their offices, trying to trust the uniforms she lied to most of her life, trying to help the same officers who once hunted her son.

Months into the investigation, the men Shonda is convinced killed Eric are still in the neighborhood. They post pictures on Facebook and Twitter with guns pointed at the camera, guns in their beds, guns coming out of their pockets. They say they would rather die than run their mouths, that talkers should die.

“I keep a pocket full of cheese to bring out all the rats,” one wrote.

She could see them driving down Dodds Avenue, pumping gas at the Kanku station or at the Bi-Lo getting a jug of milk. They’ve told her to stop blaming them publicly. But she won’t stop.

The police tell her they think she is right about the killers. Detectives tell her they are doing what they can. She tries to do the rest.

And she wonders about the fundamentals of the inner city, the code. Is it helping people?

Or is it burying them?

AS SICK AS YOUR SECRETS

“There were 20 people who saw your child murdered,” one said in open court. “They are sickening, sickening people.”

Scenes like the one in March 2010 in Coolidge Park grabbed attention. Hundreds gathered, and bullets hit five teenagers. People ran away from police, not toward them.

Now police say 58 percent of open homicide and shooting investigations in Chattanooga are at dead ends because of witness silence. Officers chase testimony, then another body falls. They chase some more. They say they looked. The clearance rate for homicides has dropped by nearly 30 percent. Fewer than half of shooting suspects are caught, a Chattanooga Times Free Press investigation shows. Many arrests lead to a few years, some time in juvenile detention, a slap on the wrist.

In many cases, bullets hit criminals, but they also hit boys who weren’t old enough to buy a beer. They hit Keoshia Ford, who now can’t walk or talk. She was just 13 when in 2012 she was caught between gang members, and a bullet lodged in her skull. The 17-year-old who nearly killed her is serving just two years.

The shooter of a 16-year-old pregnant girl in East Lake Courts was never caught. The shooter of a 3-year-old boy at Woodlawn Apartments who was hit in the leg when bullets came through a window was never caught.

Absent testimony has allowed killers and shooters to return to the community practically unscathed. They are woven into the fabric of places like Alton Park and East Lake. They are hated for their violence and revered for getting away with it. They send a message to the young.

Stay just a few hours at Bear’s Barber Shop and Edward Lewis will tell you about how his brother was killed five years ago, and the killer walked.

“It’s just a stigma that we as a black community have set upon our kids… if you tell then you’re snitching on us, or you tell, then you’re not a leader or you’re not part of this community,” he said.

Stand around the corner store on West 38th Street. A man selling weed will show you the bullet scar on his leg and tell how the shooter was never arrested. He didn’t want his name used. He didn’t care if the shooter was caught. “F*** the police,” he said.

Sit on the porches of East 27th Street and Theresa Gilbert will tell you about when her daughter was shot three years ago. Even though a crowd of her friends watched, no one would testify. Her child had permanent nerve damage and can’t work. The teen who shot her got two years in prison, and is back out.

“[Her friends] didn’t step up to the plate,” she said. “If they had, that young man would probably still be locked up now.”

They all say they don’t really trust police or each other, that they are still trying to forgive the system and the shooter.

They all say there is no justice here.

HOW MANY CASES CLEAR?

Police don’t sentence, they arrest. And when a case is cleared that means an arrest was made. The case is then passed to the district attorney. Of the 946 homicide cases since 2001, 838 were cleared. The national crime clearance rate has fallen over the years because of codes of silence in communities, according the U.S. Department of Justice.

Source: Tennessee Bureau of Investigations

In the early 1990s there were twice as many killings as there are now in Chattanooga. Some inner-city neighborhoods were flooded with crack cocaine, but even in the chaos people showed up to court. In 1991, a year with 49 killings in the city, 93 percent of the cases were cleared by police.

Then things changed. The War on Drugs happened. Rodney King happened. Zero-tolerance policing happened. Stop-and-frisk happened. Year by year, more witnesses stopped coming. They ignored calls and subpoenas. They changed apartments, bought throwaway cellphones.

The old mob language about rats and snitches and the “code of omerta” folded into the inner-city lexicon. The infamous video made in Baltimore called “Stop F****** Snitching” with a cameo by NBA star Carmelo Anthony spread online.

A different kind of morality crept into the neighborhood. Telling the truth wasn’t as important as standing against the police. People wore T-shirts: “Stop Snitching.” Elementary students knew the saying: “Snitches get stitches, snitches get ditches.” People cheered in hallways when a witness defied the court. Judges lashed out.

ANOTHER BODY

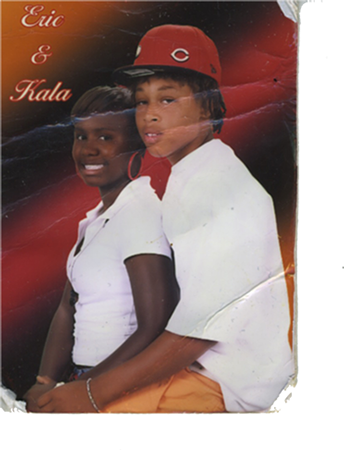

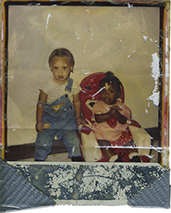

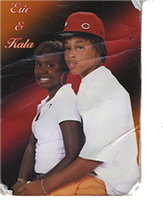

ERIC FLUELLEN

CONTRIBUTED PHOTO

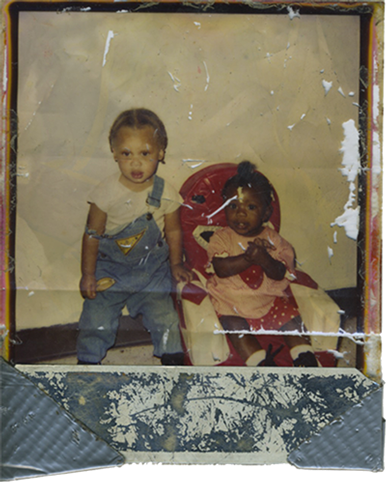

Eric Mason Fluellen was just 18, but he was already a young man people knew. He was small, 5 feet 6 inches and 120 pounds, with caramel skin. Overall handsome, aside from the dark circles drooped under his hazel eyes. In East Chattanooga people called him Lil’ E.

His father had been a career burglar. His mother had been a dealer. One of his uncles had been a gangster, and his aunt, Towanda Sherrell, walked on crutches because she was shot in the neck at 17. When Eric was 4, he watched his aunt kill his father for nearly choking his mother to death.

He was born into reputation, but he wanted one of his own.

He wanted to make money the way the other boys made money. He wanted to earn respect the way the other boys earned respect.

Stand your ground, his mother told him. You got to get out there and fight because you ain’t gonna be no pretty boy.

He acted like he wasn’t afraid to run into a drug house with a gun drawn. He acted like he wasn’t afraid to sling crack or fight or run from police, his mother said. His friends wanted to prove the same mettle, she said.

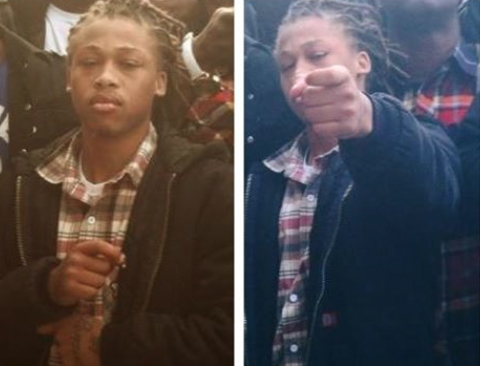

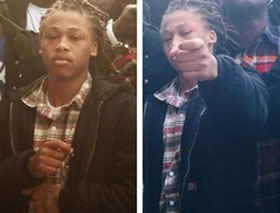

Tone Tone, born Lee Antonio Clements Jr., was rising in rank in the Foust Street sect of the Gangster Disciples. Friends said he used to be a lanky, nerdy East Ridge High School student before pictures showed him with lines cut in his eyebrows and police wrote about him hiding from officers with loaded guns in his pockets.

Skream — Dominic Wright — was scrappy, older and the same rank. He called himself “hard2kill.” Like Tone Tone, he decided who was in and who was out.

O’Shae Smith, known as Thumpa Mac, was the biggest of the three, nearly 6 feet tall and 221 pounds. He liked to pose for pictures with stacks of money.

The four men spent nights together, partied together, traveled together and ate together.

Eric hadn’t been formally beaten into the group or “blessed in” with family ties, but he wanted a spot. Tone Tone called him his “right-hand man.”

He was with those three men on March 18, a Monday. That day, Shonda said, she begged him not to leave the house with Tone Tone and Thumpa Mac. She had bailed him out of jail weeks before, and he had already started robbing again. She’d found thousands of dollars in cash hidden in a plastic houseplant, and the possible consequences were starting to terrify her. But Eric was unwilling to listen. He told her he would die for his brothers, then stuffed the money in his boxer shorts and walked out the front door.

Someone took a picture of him that night that would be posted days later on Facebook. He stood by Tone Tone in a kitchen, wearing a white T-shirt and sagging blue jeans, the same clothes he would be found dead in. His hair was pulled back, and he appeared at ease. Both of them had their hands held up with their fingers shaped like the barrel of a handgun.

Before sunrise, Skream showed up at Eric’s house to tell the family Eric was dead. Ponshala, Eric’s 16-year-old sister, was the only one home. She agreed to ride with Skream to see the body because he had been Eric’s friend. Rap music bumped through the car stereo, and he said nothing. He stopped the car on the way to the scene and got out to talk to someone.

She used her phone to call her mother.

Eric is dead.

Are you sure?

Yeah Momma.They said he dead.

When Shonda got to the scene at 13th Avenue, on that dark street where all the houses face away, the yellow tape had been strung up and groups gathered on the sidewalk. Cars cruised by slowly. Eric was out of view, shot five times in the head.

She ran to the police.

Was it really Eric?

The officer nodded.

An investigator named Chris Blackwell was assigned to the homicide. He interviewed Skream, who said he’d just happened to drive by and notice the body. Other officers knocked on doors, finishing the traditional canvass. Blackwell counted seven interviews that night, none of which led to much.

Shonda’s conversations went differently. When the uniforms weren’t nearby, people whispered that Eric had stumbled into their yard before he fell on the road to die, that they saw men wearing black run down an alleyway, that they saw a shadow behind their house, that they saw a car speed away from the body. That they heard it was a case of envy … or revenge … or money.

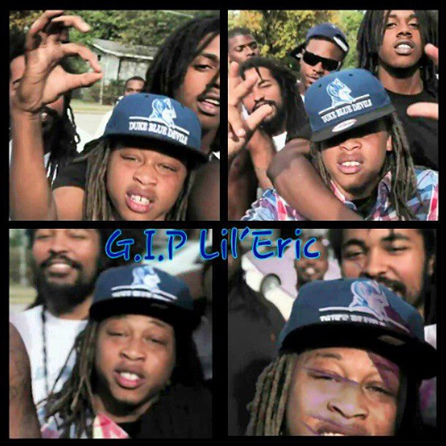

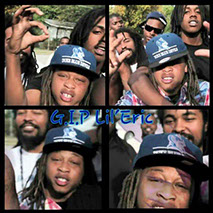

Text messages flew. Cellphones rang. Twitter ignited. “GIP LilEric,” they all said.

Another Gangster in Paradise.

ON THE INSIDE

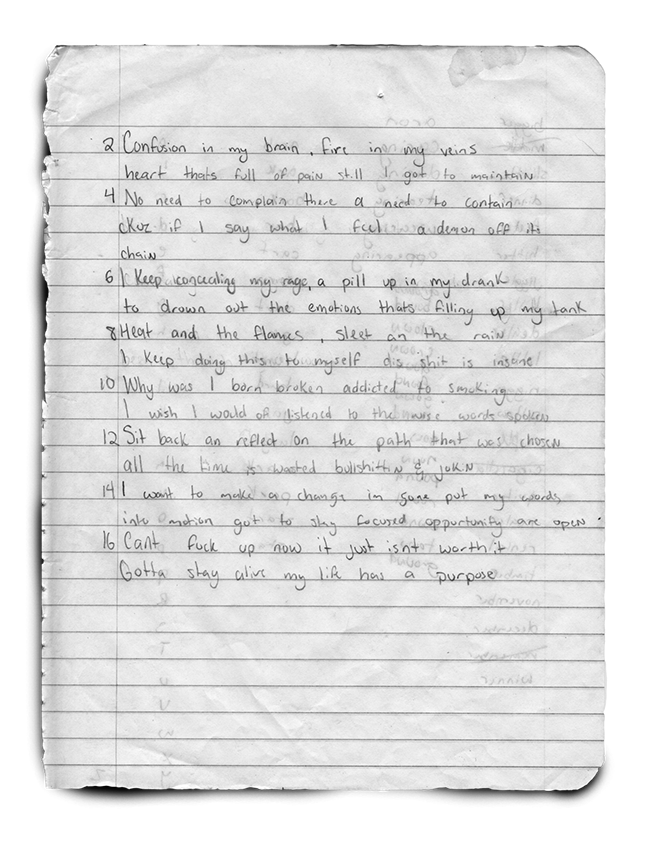

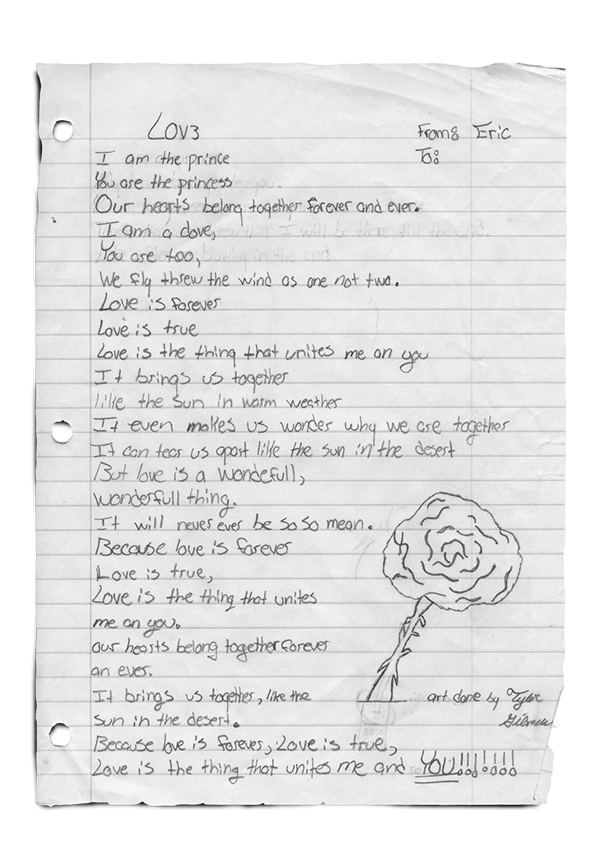

Eric Fluellen was dyslexic, placed in special education and held back several grades. In class he often wrote raps, poems and stories. When he died he left notebooks full of journal writings and loose papers that give insights into his thoughts growing up.

A SHARED EXPERIENCE

Chattanooga residents Edward Lewis, Ericka Holmes, Theresa Gilbert, Kimberly Walker, and Shonda Mason talk about the difficulty of getting people to testify in the shooting cases of their family members.

LITTLE SOLDIER

When another teen with a criminal record is buried, a part of the community breathes a sigh of relief.

Shonda’s neighbor, an aging white security guard named Mike Middleton, felt this way.

People parked in his yard to buy drugs, and that made him angry, he said. Middleton hung a sign in his yard to warn Eric: “Steal here, Die here.”

“I’m not glad he’s dead,” he said, “but I’m not going to miss him.”

Shonda believes most white people felt that way. She told friends she thought the police were probably thankful Eric was dead. She said the police would never work to resolve his case like they did for white women like Theresa Parker or Gail Palmgren, deaths that involved helicopter searches, forensic analysis, reward money and public outcry.

But she also said she believed the blacks in East Lake would play their part and keep their mouths shut. For both groups, Eric was a throwaway — not worth the time, not worth the risk. To Shonda, he was everything.

Over the years, Shonda had eight babies with four men. Her mother kicked her out of the house when she was a teenager. Her father was killed in a car accident after getting out of prison. Her sisters fought with her. Her boyfriends beat her; some stabbed her. She wanted to feel loved.

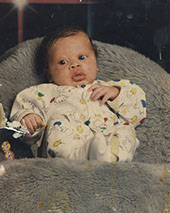

Eric was born premature with marijuana in his system, and the Department of Children’s Services later flagged his mother for “environmental neglect, lack of supervision, physical abuse and substantial risk of physical injury.” But she kept having babies who would love her, she said.

Shonda was addicted to weed, addicted to the easy money of the drug game. At times she felt unable to juggle so many children in a two-bedroom house, but no one disputed that she wanted her children.

“The mother and children are bonded,” state records read.

Eric viewed himself as the caretaker, the safety net. When her boyfriends tried to beat her, he broke in. She called him her little soldier.

He was just 10 when he helped his mother scout the empty house the family would sleep in for months. They fiddled with the electric wires to turn the power on.

If the family was hungry, he took the Walmart bags they saved, filled them in the store, drove the buggy out without paying and pushed the food home.

But when Eric was 13, Ponshala accidentally set her 1-year-old sister on a hot oven to rub lotion on her legs, and when the burned baby was seen at the hospital, the authorities split the family apart. The Department of Children’s Services deemed Shonda negligent.

His sisters and brothers were sent to relatives. Eric was sent to a stranger.

He was never the same.

Months after being taken from his mother, he was hospitalized for telling his foster parents he wanted to kill himself and others.

If I can’t go back to live with my mother, then there is no sense in remaining in this world, he told crisis workers at the scene.

He started fighting with teachers at school and refused to do assignments. No school wanted him, state records show. He ran away from foster care and went looking for his mother. Foster parents passed him along.

He grew more angry, and his crimes grew more dangerous. By 16, he faced charges for selling cocaine and attempted murder. He told counselors he was addicted to drugs like his mother and father had been. He fathered two children.

On the outside he was trigger-ready. On the inside?

“Mom, I love you. Miss you,” he wrote again and again in a journal he kept in juvenile detention. “I love God for letting me see another day.”

When he was out, he bought Shonda a multicolored dress. Crystal beading lined the waist and caught the window light when she held it to her chest. She told him she would wear it as a wedding dress one day.

He would walk her down the aisle.

BROTHERS

Tone Tone, Skream and Thumpa Mac didn’t go see Shonda after Eric’s body was found. A hush fell over the Gangster Disciples. When a gang associate is killed, it’s customary for the gang to help pay funeral expenses, but no one gave any money. The money Eric had on him that night was gone.

Shonda had expected the three men to be arrested within hours of the shooting. It was clear that Eric had been with them. Why had Skream found the body? Why had he been able to tell the family before police? But no witness would say so. The next night, she had family members call the men to come to her house.

When Tone Tone and Thumpa Mac arrived, they didn’t look her in the eye, she said. They told conflicting stories, saying Eric had gone off with a girl that night, then saying that the group had gotten into a shootout and Eric was left behind.

It was so clear they were lying, she thought.

Blackwell called them to the police station for interviews. But before questioning could start, they asked for lawyers.

At the funeral, the men showed up late and sat in a back pew. Eric’s body was on display up front, and Shonda was crying.

Can you believe they are here? someone said behind her. Towanda, her sister, walked back to confront them. A crowd formed around the scene.

Get up and leave. We know you done killed him.

Thumpa Mac smiled, slouched back into his seat, kicked up his feet and folded his arms. A cousin held Towanda back. The police, who were stationed across the street, in the back of the church and in the balcony for a moment like this, moved in and pulled the men out.

A week or so later Thumpa Mac wrote on Facebook:

“ALL DESE MIXED RUMORS ABOUT HOW LIL BRA GOT KILLED GONE MAKE ME SPAZZ DF OUT ON EVERYBODY. ANYBODY DAT KNEW ME N LIL BRA KNOW THAT I WOULD’VE TOOK A BULLET FA MY LIL SOLDIER.”

A month later he wrote this:

"LOAD IT COCC IT AIM SHOOT = BLOODY, BODY, BRAINS, WOOOO."

THE LONG WAIT

Four months passed with no arrest.

Shonda started taking medication for depression and anxiety. She watched cable. On the news she saw NFL star Aaron Hernandez arrested for a gang-related shooting. She watched the bad guys get caught on “CSI: Crime Scene Investigation,” where even dead prostitutes were quickly avenged.

“Everybody knows who did it,” said Skip Eberhardt, Shonda’s friend. “But people won’t talk … I think she is going crazy.”

She wanted the police to break down suspects’ doors and take their guns. She wanted them to bug their cars and wiretap their houses. She wanted them to find their cellphone records, she said. She told Blackwell this.

“I am just tired, man,” she said. “These people go on and live their life like nothing happened.”

Blackwell took a clinical approach to the case. He took notes about what addresses he drove to and what numbers he called. At times, he forgot Shonda’s name, but referred to his 70-page file.

Shonda told him, “I know everything from who involved on down.”

He rolled his eyes. Prove it.

Eric wasn’t the first dead teen Blackwell had seen. He had spoken with grieving parents and crying spouses. He had been called a racist and a skinhead on patrol. He had learned to disassociate himself from the cases. For many of these teenagers, these ends were inevitable. And the community seemed to do little to stop it.

“You grow callous to it,” he said. “You feel nothing.”

It was a job. Order for autopsy. Death notification. Synopsis. Interdepartmental call logs. Consent searches. Phone subpoenas. Interview reports. It was a job he wanted to do well.

He didn’t cry for Eric, but he wanted to solve the killing.

There were days when he and Investigator Lucas Fuller sat in the car on surveillance for hours at a time. There were nights when he stayed into the early morning. He tallied 56 hours of overtime for Eric’s killing; Fuller put in overtime, too. In total, records show Blackwell logged more than 1,000 hours on the case.

“I understand the family is frustrated when they continue to hear the same things,” he said. “We have to have evidence.”

One afternoon, Shonda made a round of calls from her living room. A bootlegged copy of the movie “The Purge” played in the background. The black window curtains were pulled shut. Eric’s old girlfriend, Kala Moss, answered the phone.

“What have you been hearing?” Shonda asked.

“I ain’t been hearing nothing,” the 18-year-old said.

When she hung up, Shonda sighed, grit her teeth.

People had to make an exception this time, she thought. It was Eric. People had to talk just this once.

She went to the jail to talk to a gang member who told her the plot ran deep, but also said they would never say that in court. She questioned Eric’s friends outside the gang. One boy cut his hair and threw away his cellphone because he was so scared he would be found by either the police or the gang if he talked. She logged into Eric’s old Facebook account and researched his friends. She called people who lived on Foust Street.

There was a woman she thought might have seen Eric the night he died, a female gang member. So Shonda drove to her house to confront her. Shonda screamed at the graying woman covered in tattoos.

Shonda told her she was going to find out what happened, that someone was going to be held responsible. The woman shared a little but said she could never be a court witness.

Eric had a lot of money that night and hadn’t shared it with his friends, the woman told Shonda. He didn’t have his gun because he had loaned it to someone who had left to sell drugs. A car pulled up and honked for him to come outside, she said, and Eric grabbed her hand.

Sis, I don’t want to go.

They did the brother’s handshake, the woman said.

Then, he was gone.

Chris Blackwell, 43, has been a Chattanooga police officer for nine years. He had to apply twice to get hired, and said he always wanted to be a cop. Before he became an investigator he worked patrol in Brainerd and East Lake. He lives with his wife and step children on Signal Mountain.

CHRIS BLACKWELL

CHRIS BLACKWELL

Chattanooga police Investigator

SPEAK

On a Tuesday, Blackwell parked his car in the projects and walked to a barred door. A few people sitting on their porches watched him closely. He nodded toward them and pounded.

For weeks he had been trying to interview Tone Tone’s ex-girlfriend, a thin girl with thick glasses named Teaira Howard. She didn’t answer his calls.

He looked for her at her work. He looked for her at her mother’s house. On the Internet, the cops saw that Tone Tone was threatening her.

“Yuu gne learn,” read a text conversation that Tone Tone had shared on Twitter.

“You know ain say s*** to no police,” Teaira responded. “I didn’t say s*** the first time, and the second time I didn’t say a word… and they came to my JOB and got me.

Yo weak ass friends chasing me on da way to da mall… And ain discussing s*** … I didn’t put your name on s***.”

An official at Teaira’s brother’s school gave the police similar information. Teaira’s brother, 17, had been found punching lockers. When asked what was wrong, he said his sister was in danger. She was pregnant with Tone Tone’s child and might know something about the killing of Eric Fluellen.

When Teaira answered the door, she told Blackwell he could come inside. She didn’t want the neighbors to see he was there.

“Why you been running?” Blackwell asked the 19-year-old. “I know you know something.”

Long moments went by in silence.

“Tell me what you know.”

She wrapped herself up in a blanket and sat on the end of a couch, crouching in a ball, avoiding his stare.

“Do you know anything?” he said.

Her sister in the background nodded her head, yes.

“I only know what I been hearing,” she said.

Blackwell lowered his voice and tried to sound paternal. He said he would find them a new place, far from Tone Tone, that he would keep them safe. He said talking was the right thing to do, that Shonda was devastated.

“What if this was your brother?” he said.

Teaira said she didn’t know anything.

On his way out, Teaira’s sister pulled him aside and said Teaira wouldn’t talk because she was afraid and still in love with Tone Tone. Blackwell promised he would find Teaira’s brother and find out what he knew.

He drove again to the mother’s house. He left his card. The family told him the boy was out of the state for the summer. Blackwell found him at his girlfriend’s house. He repeated the same things he said to Teaira. I know you know something. Talk.

Finally, the teen agreed. He was afraid, but he wanted to protect his sister.

Blackwell called Shonda when he got the warrant. They had charged Tone Tone with criminal homicide, aggravated assault and criminal possession, he said.

The family praised police on Facebook.

“IM SO HAPPY THEY GOT THAT B****… WHO ELSE GOIN WIT HIM???” Eric’s cousin wrote on Facebook.

“Free Tone Tone,” gang members wrote.

“UCHEERIN FA DA COPS,” wrote Thumpa Mac. “I AINT NEVA KILLED NOBODY IN MY LIFE.”

“Im not a police a** b**** but i love them for diz justice,” Eric’s cousin wrote back.

The night before the hearing, Shonda seemed calm. She drank and cooked collard greens.

If they could go away for the crime, that was good enough. That was within the law, and she was trying to trust the law.

“I miss my baby,” she said. “I need some justice.”

She expected the case to be strong, that the iron bars locking Tone Tone away would stay locked forever.

A HEARING

Blackwell didn’t tell Shonda, but in the days leading up to the hearing he began to worry that the case would fall apart.

The witness’s mother had not wanted him involved. His sister, Teaira, had been visiting Tone Tone in jail. She wrote on Twitter how sad she was to have to raise her baby alone. And in the weeks since the arrest, the boy had become shaky. Blackwell and the state prosecutor, Lance Pope, met with the witness for hours before the hearing finally began. They kept him upstairs, away from the crowd.

So many witnesses say one thing in their living room and another on the stand. And any variation in testimony leaves room for questions about credibility. Defense attorneys prey on mistakes.

Tone Tone came out in a red jumpsuit. Blackwell straightened his tie. The witness raised his right hand. Tone Tone’s family and friends watched from the front row.

“Did you have a conversation with Mr. Clements outside of East Ridge High School?” the prosecutor asked.

“Yes … I was with my girlfriend …” he trailed off.

“This microphone is recording. The judge has to understand the words you are saying.”

“All right,” he said. “She was saying …” he trailed off again.

“Speak up,” the judge said.

“I walked up to his vehicle in front of the school … I asked him if he knew anything about that,” he said.

The prosecutor stopped him.

“You said, ‘Do you know anything about that?’ What were you talking about?”

“The shooting,” the witness said.

“What shooting?”

“The Eric Fluel …”

“I can’t understand what you are saying so I know the judge can’t understand what you are saying,” the prosecutor said. “I need you to slow down and speak up. You said do you know anything about that shooting? … What did he say to you in response? … What did he say initially when you asked him about the shooting?”

“That he had passed the gun to O’Shae,” the witness said.

Shonda leaned in closer to hear.

“What did you say to Mr. Clements when he said he passed the gun to O’Shae?”

“I said I know you didn’t,” the witness said. “I know you better than that.”

“What did he tell you?”

“That he had shot him.”

Shonda couldn’t believe she heard the words. In the moment, she thought she had been wrong, about everyone. The police would solve the case. A witness would speak. Her son’s death would matter.

Then the defense attorney started cross-examination, and a pit formed in her stomach.

The attorney pointed out that the teen had changed his story. At first, the witness said he talked to Tone Tone at his home. Then he said he talked to Tone Tone at his school.

The attorney also questioned his motivation. Wasn’t the family angry at Tone Tone for leaving Teaira while pregnant, for finding another girlfriend? Hamilton County Sessions Court Judge Clarence Shattuck took it all in before he spoke.

There was probable cause, he said. So he would pass it on to the grand jury. But the case had weaknesses. So he lowered Tone Tone’s bond from $900,000 to $250,000. With a bondsman, it would cost $25,000 or less to get him released from jail.

The witness leaned in to his mother. “I guess I’ll have to move.”

Tone Tone smiled.

As everyone left the courtroom, Shonda was sent into a side room by the court officer so that she wouldn’t run into Tone Tone’s family. And when the door closed, she wept.

Give me a paper, she said. “I am going to write the judge a letter.”

She collapsed in a chair.

“He’s going to get back out.”

NIGHTMARES

No one speaks.

In mid-December, Tone Tone remained in jail because of charges brought against him that were unrelated to Eric. Thumpa Mac was also locked up for gun charges unrelated to Eric.

But Shonda expects them back out. Blackwell can’t really disagree with her. No one will go away forever for Eric’s death. No better witness has come forward. Shonda doesn’t believe the 17-year-old will come back to court.

Eric’s 19th birthday came and went. His brothers and sisters and daughter laid flowers at his grave. Shonda stayed alone at the house. She thinks too much these days, she said.

She thinks about why she hated the police and about the years she lied to them for Eric and herself. She thinks about what would have happened if she had taught her son not to lie. Would he have died earlier? Would he have died a snitch? She thinks about what would have happened if she hadn’t bailed him out that last time, just three weeks before he was killed. She didn’t want Eric to go to prison. Now he is dead.

On her dresser, she taped the one picture she had of Eric smiling.

On her shoulder, she got a tattoo of Eric’s face. It doesn’t look just like him, but it’s close enough.

She keeps a gun tucked between her mattress and box spring, just in case. Shadowy nightmares come and go. Always the same scene:

The gun in her hand. The barrel pressed to their temples, and then, like an executioner — click.

The bodies lie on the street where the houses face away and the streetlights are broken.

A crowd watches.