From 2011 to 2013, states passed more laws to restrict abortion than in the prior three decades, according to the Guttmacher Institute, a nonprofit that researches reproductive health, loosely affiliated with Planned Parenthood. Some states, such as Texas and Mississippi, have all but banned abortion in recent years, passing laws that require ultrasounds and waiting periods. Texas enacted a law a year ago that required the state’s 40 licensed abortion providers to have admitting privileges at hospitals. Now, only eight providers remain. In Mississippi, only one clinic is left.

Currently, Tennessee has a few laws governing abortion — minors must have parental consent, the “abortion pill” must be prescribed to a woman in-person, and physicians who perform abortions must have admitting privileges to hospitals. Also, public funding for abortion is highly restrictive.

Tennessee could follow the same course as Texas, Louisiana, Alabama, and Mississippi, all of which are quickly losing abortion providers. Amendment 1, which will be on the state’s Tuesday ballot, asks Tennesseans whether they agree that there is nothing in the state constitution that guarantees a woman’s right to an abortion.

If the “yes” votes win, the General Assembly will be free to enact legislation that regulates abortion, including new standards for abortion facilities and laws that make no exceptions for victims of rape, incest, or the health or life of the mother.

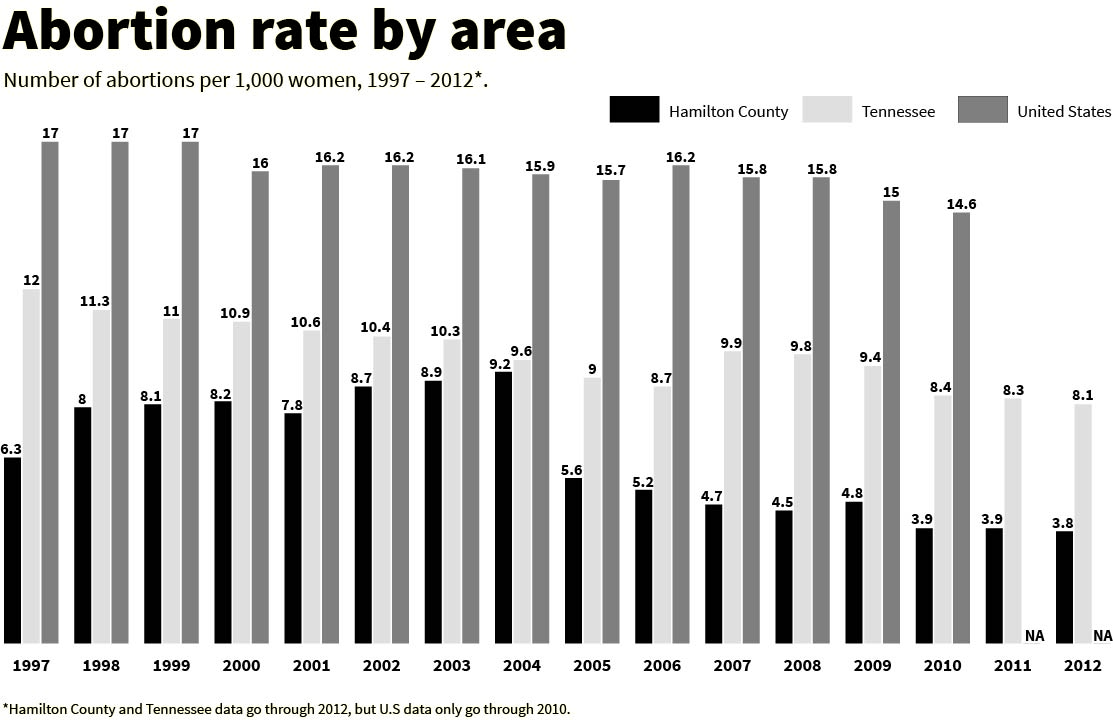

The abortion rate in Hamilton County has been on a steady decline for the past 10 years. As a whole, women from Tennessee had abortions twice as frequently as women from Hamilton County, according to 2012 data from Tennessee’s Department of Health. The U.S. abortion rate was three times as high as the rate in Hamilton County in 2010, according to the newest available data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

At current rates in the U.S., about one in three women will have had an abortion by the time she is 45, according to the Guttmacher Institute. But in Chattanooga, the rate is low and dropping. For every 1,000 women aged 15 to 44 from Hamilton County, 3.8 received abortions in 2012, the most recent data show. The rate for Tennessee that year was 8.1. It’s the lowest rate for both Tennessee and Hamilton County, since the state began keeping records in 1997.

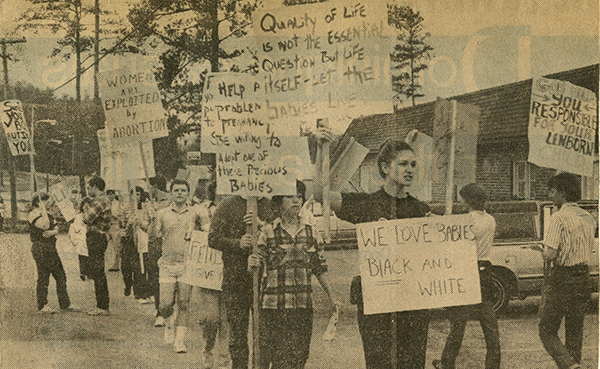

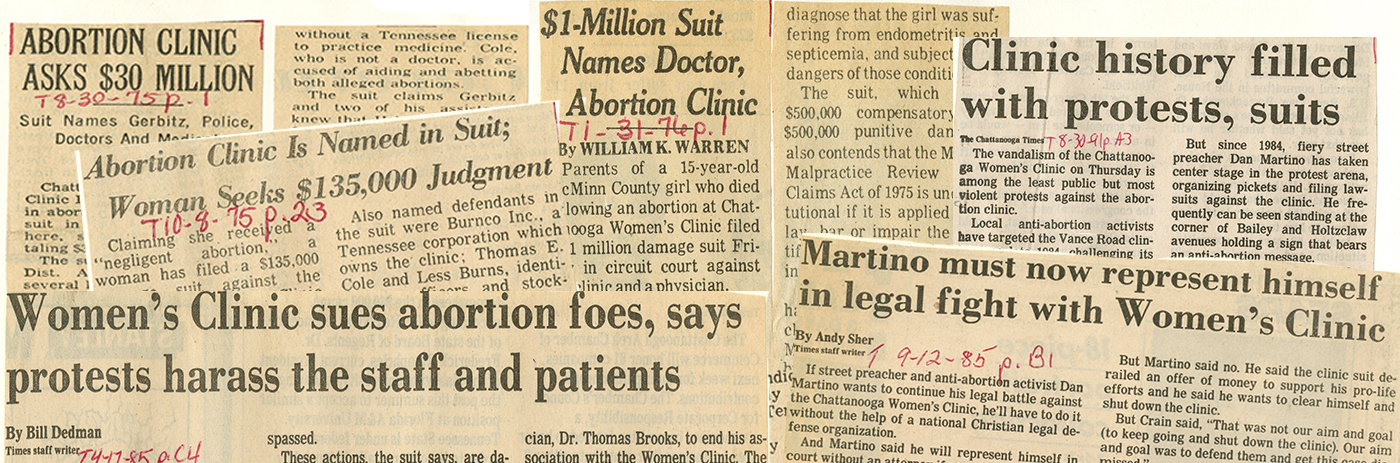

Protesting against the procedure in Chattanooga today is all but irrelevant.

But the debate over whether there should be an abortion provider in Chattanooga may soon bubble up again.

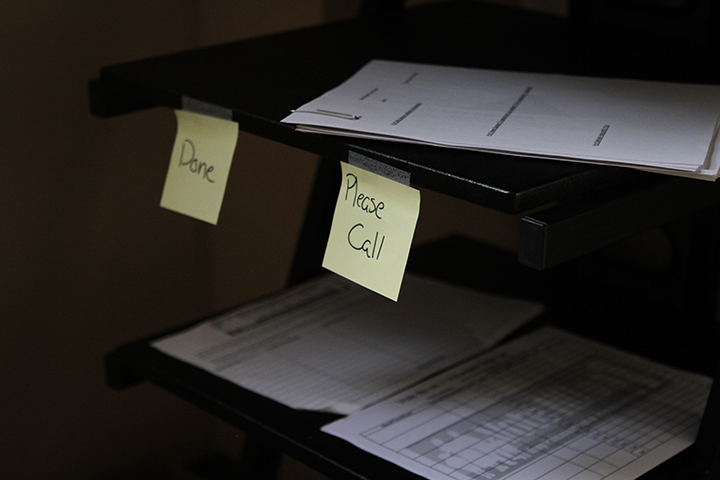

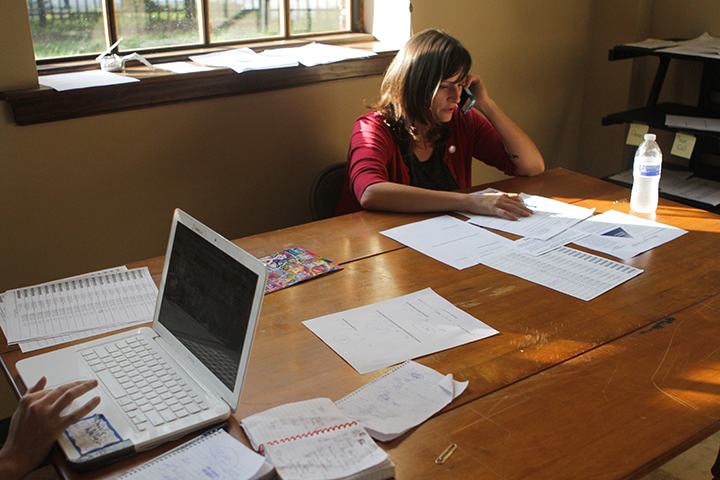

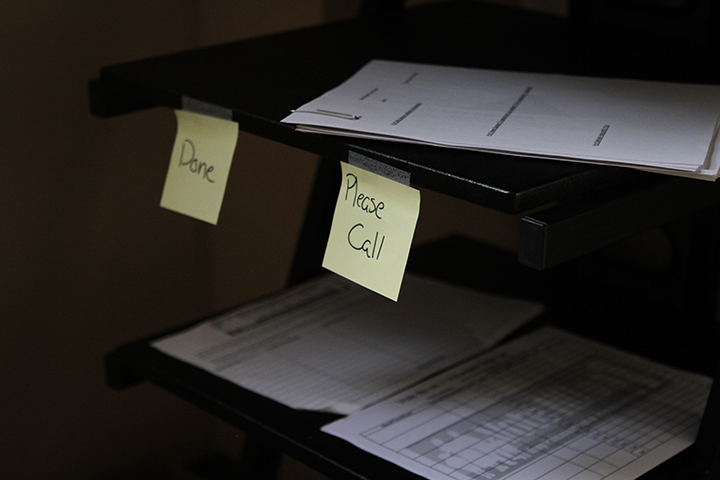

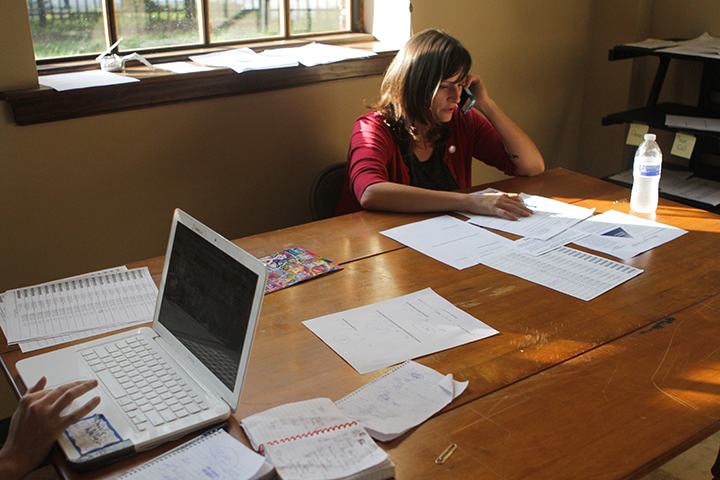

(Top) Piles of numbers sit sorted for a phone bank at the Vote No on 1 field office on September 16, 2014 in Chattanooga, Tenn. (Bottom) Volunteer Christina Sacco calls voters at a phone bank at the Vote No on 1 field office on September 16, 2014 in Chattanooga, Tenn.

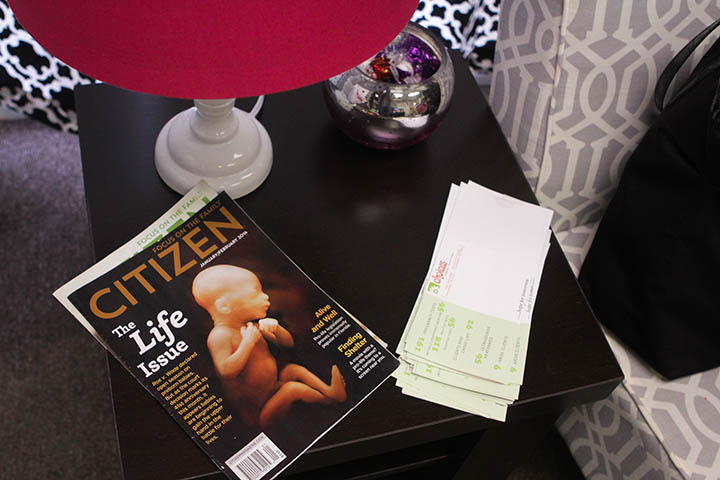

A new pro-choice group, Choice Chattanooga, has been working since January to reassert a woman’s right to her own body and to an abortion. Organizers have spent the last several months campaigning for people to vote against Amendment 1, but they have bigger dreams. They want to bring abortion services back to Chattanooga.

“We want to get a Planned Parenthood here, and if an amendment like this were to pass, that would be one more obstacle,” said Lauren Kramer, one of the organization’s founders.

Lauren Kramer, a co-founder of Choice Chattanooga and Vote No on 1 field organizer orients volunteer Landon Howard to phone bank at the Vote No on 1 field office on September 16, 2014 in Chattanooga, Tenn.