Members and spectators watch from their pews as pastor Andrew Hamblin prays over a group of men at the Tabernacle Church of God in LaFollette, Tenn. The pastor has become the unofficial face of Appalachian snake handlers. Hamblin, just 22, is working to bring his obscure brand of Christianity into the mainstream.

Even unto death

These believers drink poison. Handle snakes. Risk all in the name of the Lord. For a century, their audacious brand of faith has been practiced out of sight in the Appalachian hills.

Now a new generation of pastors pulls back the curtain, bringing souls and serpents into the light.

Story by Kevin Hardy

Photography by Dan Henry

Sights and sounds from the Tabernacle Church of God in LaFollette, Tenn., and the Full Gospel Tabernacle in Jesus Name in Middlesboro, Ky.

"And these signs shall follow them that believe: In my name shall they cast out devils; they shall speak with new tongues; They shall take up serpents; and if they drink any deadly thing, it shall not hurt them; they shall lay hands on the sick,

and they shall recover."

— Mark 16:17-18

King James Bible

LAFOLLETTE, Tenn. — This place doesn’t look like much.

The brick exterior is falling away. The homemade sign standing by the dead-end gravel road is written in crooked stencil lettering.

“Tabernacle Church of God. Pastor Andrew Hamblin. Friday 7:30. Sunday 1:00.”

But there is no meekness inside this windowless, concrete box of a church. Sound explodes and escalates, a chaotic jumble of tambourines, electric guitar and humming.

At times the volume is so loud it rattles the foundation. Foreheads gleam from olive oil anointing, tongues mumble unrecognizably, hallelujahs scream to the ceiling, arms stretch wide.

There will be a miracle tonight.

It’s in the air.

People can feel it.

Someone could drink from a pickle jar filled with strychnine or lye, but not fall dead. Someone could turn a propane torch to his hand and feel no pain. Someone could wrangle a rattlesnake and not feel its fangs.

The sign for the Tabernacle Church of God hangs just down a gravel road in LaFollette, Tenn.

“Taking away our snakes is like taking away the Baptists’ Bibles. Or the Catholics’ communion.”

— Andrew Hamblin

Places like this used to be private, secrets tucked away in the hills. Now many people travel from across the country, even the world, to sit in a pew and bear witness to the sights and sounds of this church, to see these people flirt with death. But to the congregants — the families who have worshipped this way for generations, the former alcoholics and drug users who are looking for a sign — this is salvation.

The outsiders want to see the rattlesnakes, but snakes don’t always appear during worship. Sometimes they remain curling in a box on the edge of the altar, untouched. They only come out when there is a call, when God tells a believer to take up the danger and trust Him.

For nearly an hour the music plays, a blues sound with a contagious rhythm.

Then, a frenzy begins to build. The music intensifies. The cries grow louder. Some stumble in trances, each person immersed in his or her own experience.

Outsiders peer through the chaos to see what happens next.

The pastor, Hamblin, sets down his guitar and walks away from the pulpit toward the box on the floor. He says his soul is churning. He must obey.

There is death in that box, he likes to tell people. He’s been bitten before. He’s seen men die in moments like these, good men, righteous men.

But when he grips his hand around the middle of the rattler, almost no one seems afraid.

He juggles the coils of patterned scales until the head is erect, stretching toward him, and he believes that this time, like so many others, God will hold the serpent’s mouth shut.

.jpg)

Andrew Hamblin, the 22-year-old pastor of the Tabernacle Church of God, preaches at a recent service while grasping a canebrake rattlesnake. Hamblin has become a sensation, broadcasting the century-old tradition of Appalachian snake handling through YouTube, Facebook and reality TV.

These believers live and die by their obscure brand of faith

To understand modern-day serpent handing you have to go back to White Oak Mountain, a ridge that straddles the Hamilton and Bradley county lines. You have to go back to the early 1900s and George Hensley, a man whom some have called a moonshiner, an illiterate.

While serpent handling may have surfaced in churches before Hensley, the Tennessee native is credited for evangelizing the practice across Appalachia and drawing the world’s attention to his audacious brand of Pentecostalism.

A drunk who often struggled to keep steady work, Hensley sought redemption, and believed it could be found in a portion of the Book of Mark where Jesus says to handle snakes in his name.

On White Oak Mountain, he picked up his first snake as an act of obedience and quickly began recruiting followers, traveling across Appalachia and the Ozarks to plant churches that all functioned independently.

But the main vehicle for spreading his beliefs was as a pastor in the Cleveland-based Church of God, now the largest Pentecostal denomination in the world. The church once embraced snake handling, but has disavowed the practice for more than half a century.

"I think a person who goes down here and offers a piece of bread to a hungry person, a coat to a person without a coat, a drink of water to a thirsty person, I think they're proving their faith in just as effective, a more effective, way."

— The Rev. Mike Hubble,

the Chattanooga District superintendent for the United Methodist Church

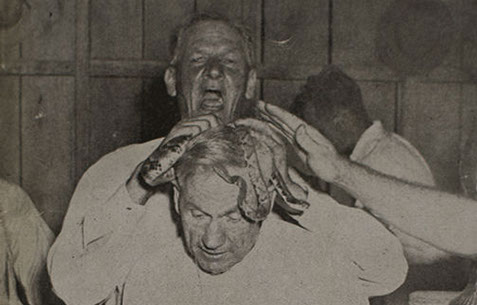

Archival photo

Preacher George Hensley has a crown of snakes placed on his head in the 1940s at Hamilton County's Dolley Pond Church of God with Signs Following. Hensley is widely credited with spreading the Christian practice of serpent handling throughout Appalachia. Former Chattanooga News-Free Press reporter J.B. Collins captured the drama of a snake bite-death and police raids at Dolley Pond in his pamphlet “Tennessee Snake Handlers.”

Video

Snake handling expert and UTC professor Ralph Hood gives context to the history of snake handling in Appalachia.

At churches inspired by Hensley’s revelation, snakes would wrap around bodies, sometimes crawling out of shirt collars, sometimes coiling into crowns that were placed on believers' heads. Members would fight over snakes or walk barefoot on buzzing serpents ready to strike.

“Cultists claim that often one of their members are filled with such strong power ‘like electricity’ that the snake being fondled is ‘shocked to death,'" Chattanooga News-Free Press reporter J.B. Collins wrote in a 1940s pamphlet about snake handlers in Hamilton County.

Then Hensley’s followers started dying.

In 1945, a truck driver in his 30s was bitten during a large church service at the Dolley Pond Church of God with Signs Following in Hamilton County. He refused medical care and died in front of news reporters 70 minutes after he was bitten.

During the funeral service, six live snakes — including the one that killed him — were placed in the coffin over Lewis Ford’s face, Collins wrote in his pamphlet on Tennessee snake handlers.

The words and images that came out of Dolley Pond became a sensation. Chattanooga newspapers sent stories across the globe. Southern states reacted by outlawing the handling of serpents, and believers were decried in the media as ignorant cultists.

And the publicity, the deaths, stunted the church, which had been spreading in Bible country.

Churches that had held homecomings with hundreds shriveled to almost nothing. The practice became part of Southern folklore, an oddity that many can’t believe still exists. Grandparents would tell their grandchildren, "Did you know there are people still worshiping with snakes around these mountains?"

The faith survived, even as the death toll climbed. Families passed down their beliefs and picked up a few converts along the way. Now scholars estimate 100 “signs-following” churches remain in states including Kentucky, Alabama, Tennessee, Georgia, North Carolina and West Virginia with a few thousand members at most.

Pastor Jamie Coots, right, plays an electric guitar during a recent Wednesday evening service at the Full Gospel Tabernacle in Jesus Name church, left, in Middlesboro, Ky. Coots is the third generation to lead the serpent-handling church his relatives built on family land.

And now two younger pastors, including 22-year-old Hamblin, want to open the church’s doors and stop the seclusion that has persisted and defined the church for more than 60 years. Facebook groups have been started. YouTube videos of services appear online. Television crews have been allowed into churches for cable broadcast.

Hamblin, especially, envisions serpent handling going mainstream. He hopes a spotlight, even a court fight, will help him win more followers, or at least secure acceptance.

Experts say his push is important to watch because it will test the limits of America’s commitment to religious liberty. Snakes can maim and kill, but they are essential to these people’s faith. It opens the door to an important question: Should the government protect people from themselves? Or leave them to do what they think is right, regardless of the risk?

“Taking away our snakes is like taking away the Baptists’ Bibles. Or the Catholics’ communion,” Hamblin said.

Still, the future of these churches is dubious. Most people view snake handling as crazy, and religious authorities say snakes will never find a place in conventional Christianity.

“I think that most people would not think that that was how they had to prove their faith,” said the Rev. Mike Hubble, the Chattanooga District Superintendent for the United Methodist Church. “I think a person who goes down here and offers a piece of bread to a hungry person, a coat to a person without a coat, a drink of water to a thirsty person, I think they’re proving their faith in just as effective, a more effective, way.”

And within the church, a divide may be forming between those who want to welcome the public and those who prefer private devotion.

Congregants gather around Pastor Jamie Coots at the Full Gospel Tabernacle in Jesus Name church in Middlesboro, Ky., where members handle fire, speak in tongues, take up serpents and drink poison. In this small sect of Pentecostalism, services are emotionally driven, filled with dancing, tambourines, guitars and fitful worship.

A new kind of "signs-following" pastor takes up the serpent

Hamblin grew up in an unincorporated town not far from the Northeast Tennessee church he founded and now pastors. Coal mining jobs were coveted and trailer homes dotted the terrain. Here, nearly a third of the people don't finish high school and the median family income is some 30 percent lower than the rest of the state.

His grandparents raised him after his parents divorced. His Papaw was a preacher at a Free Will Baptist church, a charismatic church that believed in speaking in tongues and the healing of the sick.

Hamblin believed what he heard in church but said he also made mistakes.

He got his girlfriend Elizabeth pregnant when she was 16 and had to drop out of high school to support the family. The two married a few years later and he paid the bills with odd jobs. He ran the register at Dollar General, worked the counter at a movie store and stood guard as a night watchman.

Then, at 17, he learned about serpent handlers.

He remembers watching a television show explaining the practice, and he was intrigued. He read books, watched Internet clips and studied his King James Bible, especially the passage in Mark on which serpent handlers base their practice. Biblical scholars, as noted in many study Bibles, say that these few verses were not originally included in Mark’s Gospel, but were added later. Many experts say early Christians didn’t even know about these verses.

But there they were in Hamblin’s Bible. The commands seemed clear.

“And these signs shall follow them that believe: In my name shall they cast out devils; they shall speak with new tongues; They shall take up serpents; and if they drink any deadly thing, it shall not hurt them; they shall lay hands on the sick, and they shall recover.”

"They didn't come in here and handle a snake and get salvation. They come in here and the blood was applied to their life. They met Jesus. Some of them ain't never mentioned nothing about the serpents."

— Andrew Hamblin

Anointing oil, flammable liquid, a propane torch and poison rest on the pulpit during a Wednesday evening service at the Full Gospel Tabernacle in Jesus Name in Middlesboro, Ky. If they feel God has called them to, believers at this Pentecostal church will take a sip of poison, hold fire against their skin or pick up a deadly snake.

Not long after, he decided to experience a snake-handling church in person. He traveled just over the border, 35 miles, to the Full Gospel Tabernacle in Jesus Name in Middlesboro, Ky., where worshipers handled fire, drank poison, spoke in tongues and took up snakes.

The pastor, Jamie Coots, took over the tiny church from his father, who inherited the church from his father. They built the building on family land, and Coots’ son, now 21, was being groomed to take his father’s place. Coots took to Hamblin after their first meeting and said he would train him as a minister.

Over several months, Coots taught Hamblin the basic tenets of the “signs following” faith:

Jesus Christ is the son of God that died for sins and is the only way to salvation.

The Bible should be read plainly — when it says “they shall take up serpents,” it means we should take up serpents.

The faithful can achieve righteousness on Earth and should show they are different — holy.

Services are always driven by the spirit of God. Some will handle snakes on faith alone, but it’s best to wait on the Holy Spirit’s anointing.

Don’t worry too much about the law. They usually turn a blind eye, unless you are in Tennessee.

There is no central authority, convention, association or assembly. Each church determines its own rules.

In Coots’ church, for example, women were told to wear long dresses and not cut their hair. Sex outside of marriage was forbidden, along with remarriage, drinking, cursing and gambling. Congregants were urged not to listen to rock, rap or country music, only gospel.

Christ didn’t do these things, Coots said, and neither should we.

“We are supposed to be separate,” he said. “How can we shine a light if people don’t see a light in us?”

Together, Coots and Hamblin attended summer homecomings in West Virginia and Kentucky, where dozens of handlers came together and held snakes elbow to elbow.

“You could feel the spirit of God moving,” Hamblin said.

And in August 2009 Hamblin took up his first snake. A rattlesnake. Black.

The rush overwhelmed him. His spine tingled.

He survived.

.jpg)

Gregory Coots, the father of Pastor Jamie Coots, clutches two canebrake rattlesnakes during a recent Wednesday evening service at the Full Gospel Tabernacle in Jesus Name church in Middlesboro, Ky. Handling serpents is an extreme show of faith still practiced by an estimated 100 churches across Appalachia.

The world comes calling,

and the whispers begin

"They are suspicious of the flamboyancy without the credibility. The bottom line with these people is they believe in living a holy life."

– Ralph Hood, a University of Tennessee at Chattanooga psychology professor and one of the nation's leading experts on Appalachian snake handling.

Two years later, Hamblin started posting dozens of pictures on his Facebook page of himself holding fat rattlers up in the air. Some people who posted called him stupid and chided him for testing God.

“Andrew you better be careful,” wrote one friend.

Others praised his path. Only the holy can handle snakes, some friends said.

“Take them up son, if you don’t obey the WORD OF GOD you will die lost and go to a DEVIL’S HELL!!!,” Coots wrote in response.

In 2012, the Wall Street Journal took notice and wrote an article about Hamblin and his efforts to reach young people with the “signs-following” tradition. Not long afterward, the National Geographic Channel noticed him as well.

Producers called Ralph Hood, a University of Tennessee at Chattanooga psychology professor and one of the nation’s leading experts on Appalachian snake-handing traditions, to see if he thought Hamblin would be willing to star in a show about serpent handling.

This was a position Hood had been in before. Journalists and television producers often asked him about his 30-plus years of research on “signs following” believers. At UTC’s Lupton Library, he had amassed the world’s largest collection of footage and photos documenting serpent handling back to its roots on White Oak Mountain.

When Coots and Hamblin got the call, they decided to break ranks with many older church leaders who believed media involvement would bring trouble. Coots had courted television before and made an appearance on a National Geographic show.

And in 2012, the two started filming “Snake Salvation.” Coots, Hamblin and others were paid for their appearances on the show and producers covered many expenses like hotels, meals and gas costs throughout filming.

The pastors, some of the first to speak so publicly about their faith, hoped it would draw empathy from skeptics. These churches are about more than snakes, they said. Attendees found forgiveness and started a righteous path.

“They didn’t come in here and handle a snake and get salvation,” Hamblin said. “They come in here and the blood was applied to their life. They met Jesus. Some of them ain’t never mentioned nothing about the serpents.”

But in the final cut, the show focused more on snakes than souls.

Congregants of the Tabernacle Church of God, clockwise from top left: Pastor Andrew Hamblin, left, holds hands with Ronnie Daugherty in prayer, Linda Spoon smiles while welcoming attendees, Jeremy Henegar greets the crowd and Glenna Daugherty becomes emotional after praying at the altar.

Footage showed Hamblin desperately searching for snakes in the woods and managing a dingy back room filled with snake cages. There was snake cleaning, snake shopping and snake feeding. It showed Hamblin and Coots promising that their snakes were truly dangerous, that they weren’t milked or defanged like some say. Hamblin showed the bite scars on his hand. Coots showed the stub of his middle finger left from a bite. He keeps the rest of the finger in a jar.

Hamblin was discouraged about the show’s editing. But he also enjoyed the attention.

A large banner of the pastor holding up a snake hangs on the sanctuary wall in the LaFollette church. He and Coots had done what many believers before them were afraid to do, he said.

“What’s the matter with the snake-handling people?” Hamblin said. “… The world considered them ignorant, illiterate, redneck hillbillies that married their sisters’ cousins. Because they wouldn’t step out and show the world they wasn’t.”

The show attracted people like Lewis Carroll, a construction worker who said he drank a case of beer a day before coming to Hamblin’s church.

“A lot of people believe this church is about snake handling and it’s not. This church is about helping people,” he said. “I am scared to death of snakes. If I ever handle, it will definitely be God telling me to, and I want to be sure it’s God’s voice.”

Lewis Carroll, left, takes a seat in the front pew under a poster of Pastor Andrew Hamblin an hour before service begins at the Tabernacle Church of God in LaFollette, Tenn. Carroll said he drank a case of beer every day before turning his life around by attending church here.

But the publicity drew negative attention, too. People called Hamblin a false prophet.

“...Ur nothing but an ignorant radical freak and im gonna laugh when one of those snakes u play w bites somebody and hurts them bad or kills them u freak,” Patrick Matlock wrote on Facebook.

On one episode, the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency cited Coots for trafficking snakes through the state. A few weeks after the series finale, Hamblin was also charged with a misdemeanor.

Wildlife officers escorted him to his church, where they confiscated 53 venomous snakes. Many were emaciated and diseased, the officers said, and more than half died. The rest were later euthanized.

The TWRA charged Coots and Hamblin with violating the state’s wildlife laws. But many states, including Tennessee, have laws that ban handling venomous snakes — laws that have withstood court review thanks in large part to the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling upholding bans on polygamy. The court ruled in 1878 that the government may regulate certain religious practices if they were viewed as dangerous to society.

So Mormons could believe in polygamy, they just couldn’t practice it. Same goes for snake handlers.

Hamblin saw the confiscation and his case as a chance to rally support. Outside the Campbell County Courthouse and in interviews, he called for a change in Tennessee’s strict laws that make it nearly impossible for a private citizen to own a poisonous snake.

Supporters wore red ribbons. His disciples were there, but so were Catholics, other Protestants and Vietnam veterans, who all said his church ought to be left alone.

At one time, fewer than a dozen attended church with Hamblin. Now more than 80 people could attend a service. Many have converted. Others come to gawk.

“Sometimes a man can talk too much and cause a lot of trouble. There are some things they should have left alone.”

— pastor Harvey Payne

Pastor Andrew Hamblin lays hands on a member of the crowd at the Tabernacle Church of God in LaFollette, Tenn. Hamblin, just 22, has become the unlikely face of serpent-handling thanks in large part to a high-profile court case and reality TV appearance.

In January, the Campbell County grand jury declined to indict Hamblin. He and his followers called it a victory, a win for religious liberty. He thinks his fight could help him relate to other Christians who want to pray in public meetings or hang the Ten Commandments in courthouses.

But the laws aren’t likely to change. What legislator wants to champion snake handling?

“We don’t want to be known as the serpent-handling capital of the world,” Hood said. “It’s not a good PR thing — we have Volkswagen and we handle serpents.”

Since Hamblin has become the unofficial spokesman for snake handlers, there have been whispers from among the more traditional members of the community.

Hood hears many of the concerns while conducting his research. Maybe Hamblin, who is now feeding his family of five children on food stamps and the goodwill of followers, just wants to be famous. Maybe he is an adrenaline junkie.

“They should have just kept things to themselves,” said Harvey Payne, a fellow serpent-handling pastor. “Sometimes a man can talk too much and cause a lot of trouble. There are some things they should have left alone.”

Payne leads the Church of the Lord Jesus with Signs Following in Jolo, W.Va., where believers have handled snakes for generations. While his church would never agree to a TV show, Payne understands the urge to revive the faith. His church has shrunk and congregants are getting older.

“You wonder about it. It is a dying thing,” he said.

Hood hears other concerns: Hamblin is an outsider. He’s too young. He didn’t take good care of his snakes. He had a baby out of wedlock. He smokes cigarettes. He doesn’t require women to wear skirts. He believes that bitten believers can receive medical attention, while many others don’t.

“They are suspicious of the flamboyancy without the credibility,” Hood said. “The bottom line with these people is they believe in living a holy life.”

Hamblin said he knows people question him. But the Pharisees questioned Jesus, too, he said.

“He is clearly a charismatic guy, and he has gotten all these young people who have never been involved with the tradition,” Hood said. “He is kind of making his own way.”

Liz Hamblin, right, takes a photo of Sue and Tim Ramsey with her husband Andrew Hamblin, the 22-year-old pastor of Tabernacle Church of God, a snake-handling church in LaFollette, Tenn. Nowadays, Hamblin's church is regularly home to visitors like The Ramseys, who drove down from Baltimore, to attend the Friday evening service.

“Snake Salvation” wasn’t picked up for a second season. And some say Hamblin’s victory over the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency will make him even more of a target.

Still, he talks about the bright future of his church. He’s raising money to fix up the deteriorating building. He says he’s gotten letters from atheists and agnostics who say they didn’t believe there was a God until they saw him on television holding a snake in his bare hands.

Many of Hamblin’s followers say they are former drunks, drug addicts and potential suicides who have changed their lives for the better since coming to his church. And they are spreading the word of all the good found at his church.

“If you’re really addicted or you need something, you can find it here because God dwells here,” said Jeremy Henegar, a local 20-year-old middle school janitor who said he was an alcoholic before meeting Hamblin.

“[People] seen the change in me,” Henegar said. “They’re going to want to come figure it out, too.”

The stories feed Hamblin. He imagines a megachurch in years to come, a time when his faith isn’t hidden in the hills, when snakes are legal and the congregation can raise enough money to give food to the hungry and shelter to the homeless in this poor county, where many of the coal mining jobs have vanished.

“I guarantee you people’s going to put you down. They’re gonna talk about you,” Hamblin said in a recent sermon. “They’re going to do everything they can to find fault in you.”

He asked a church member to go out into the parking lot and fill a bowl full of gravel.

Hamblin walked down the center aisle, bowl in hand.

Who wants to cast the first stone? he asked.

No one lifted a finger.

Written by Kevin Hardy

Photography and multimedia by Dan Henry

Design by Nick Fowler

Production by Maura Friedman and Ken Barrett