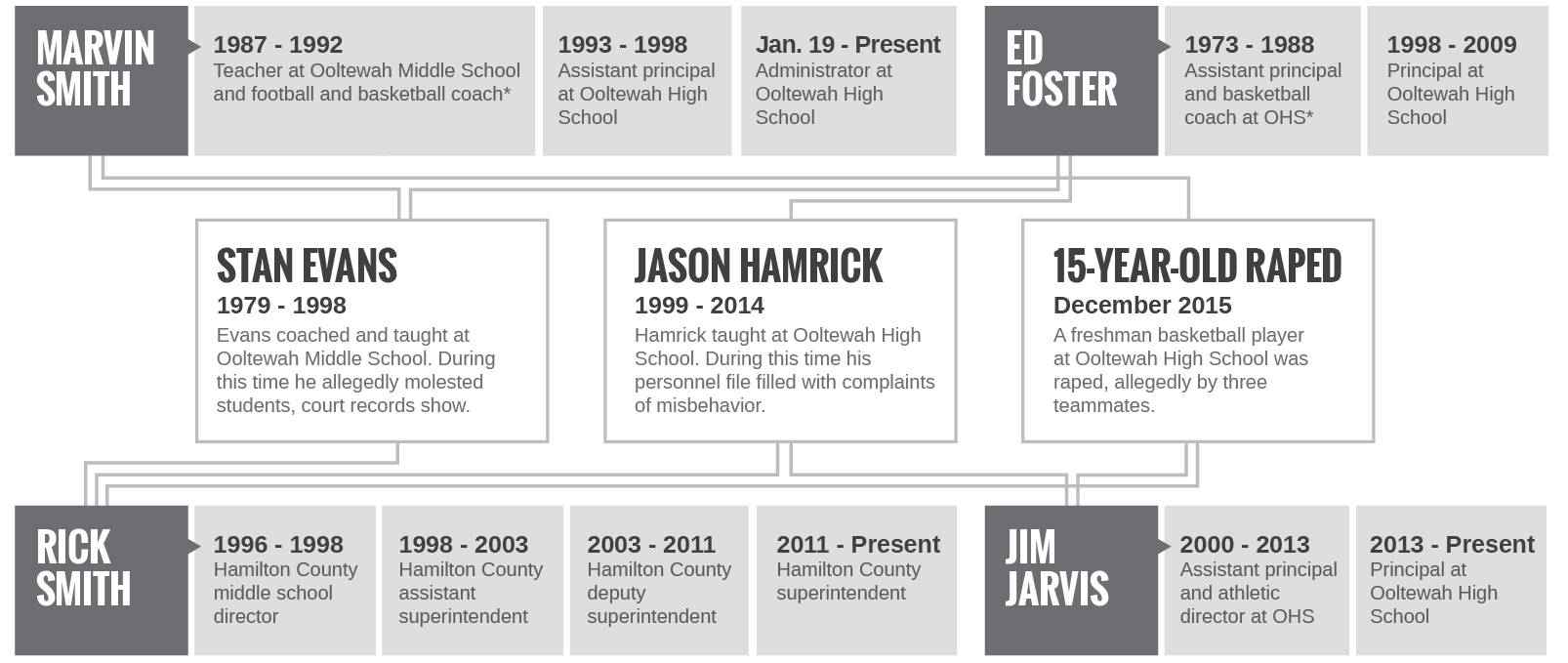

Ed Foster

- Ooltewah High School

basketball coach - East Ridge High School

administrator - Ooltewah High School

principal

For decades, school leaders at Ooltewah Middle and High schools have turned a blind eye.

Warning signs of abuse have been overlooked. Reports and suspicions of inappropriate behavior have gone unaddressed. And children have been left vulnerable and unprotected, according to school and court records, employees and former students.

Just days after Christmas, news surfaced about the rape of an Ooltewah High School freshman — two 16-year-olds held down a 15-year-old teammate as a 17-year-old raped him with a pool cue, according to court records. The three teens face charges of aggravated rape and aggravated assault, and two of their coaches and the school’s athletic director are charged with failing to report the attack to authorities. The men are scheduled to appear in court Monday.

Reports of the assault grabbed national headlines, stirring outrage and disgust.

But for others, accounts of the rape brought back memories they’d been working for years to forget, a burden they didn’t want any other kid to carry.

“It was a school system that failed me,” former student Michael Mercer said of Hamilton County Schools. “They failed to protect me, and they failed to protect this kid.”

Mercer is among several former Ooltewah students who claim coaches treated them inappropriately and that administrators were slow to respond to their allegations.

Mercer and nearly a dozen current and former school employees told the Times Free Press that over the years, coaches and athletes received preferential treatment and got away with acting inappropriately. Decades of such behavior created a culture of negligence where teachers, coaches and administrators look the other way, putting students in jeopardy, they say.

And they believe this culture ultimately enabled a rape so violent the victim had to have surgery.

The employees spoke to the Times Free Press on the condition of anonymity for fear of retaliation.

Records show that years before the December attack, graduates and parents of Ooltewah High School students complained about at least two coaches behaving inappropriately toward students — giving back rubs, sharing hotel rooms and touching them — and administrators took years to act on the complaints.

Some of those who allegedly failed to protect students years ago are now in charge of Hamilton County Schools or still connected to Ooltewah High School.

Superintendent Rick Smith received complaints about the two coaches, although he said he dealt with the concerns swiftly. Ooltewah High School Principal Jim Jarvis was an assistant principal at the school during one of the prior complaints. Retired administrator Marvin Smith, recently assigned to fill in at Ooltewah High School in the wake of the rape, also received complaints about one of the two previous cases.

An Ooltewah High School teacher said he’s concerned the same people who did nothing in the earlier cases are still in power.

“I don’t think our children are protected,” the teacher said.

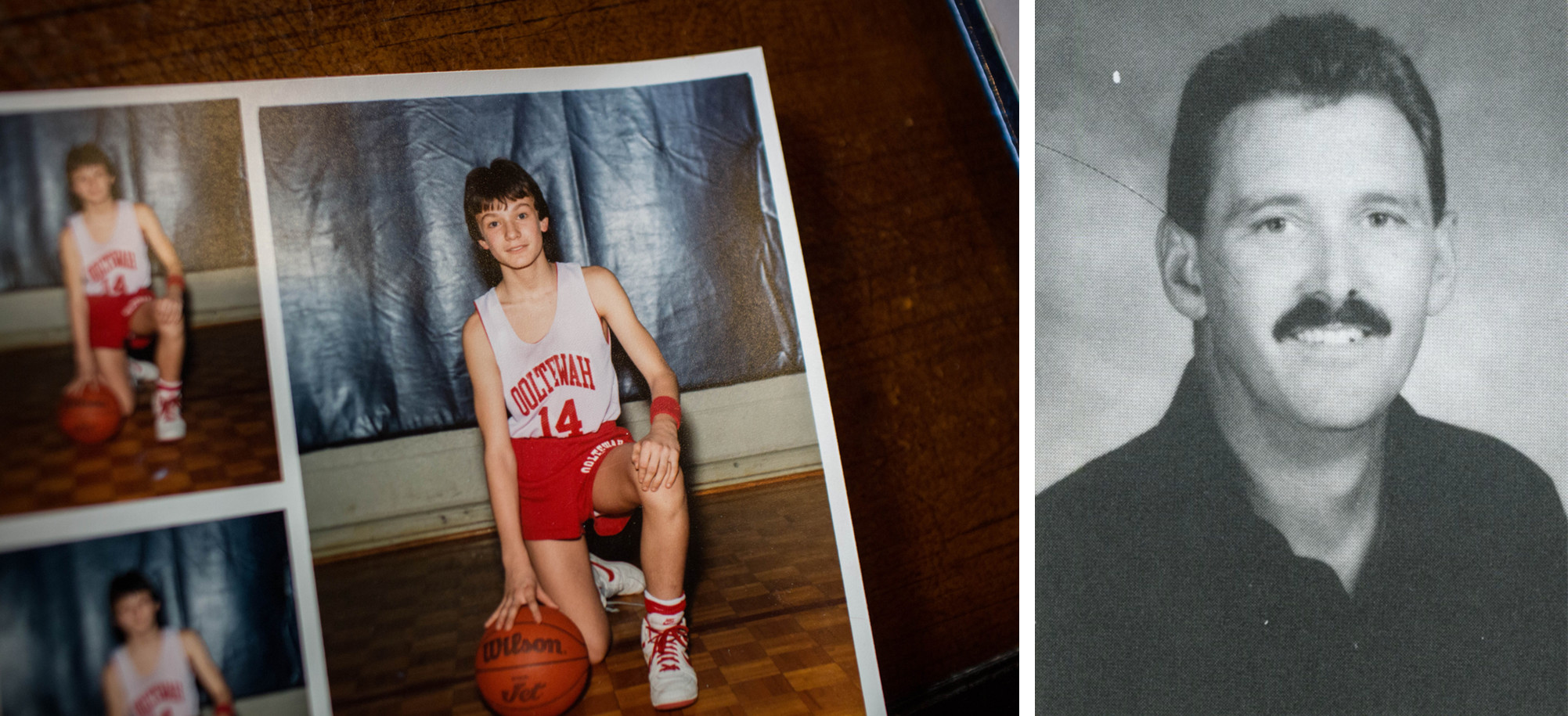

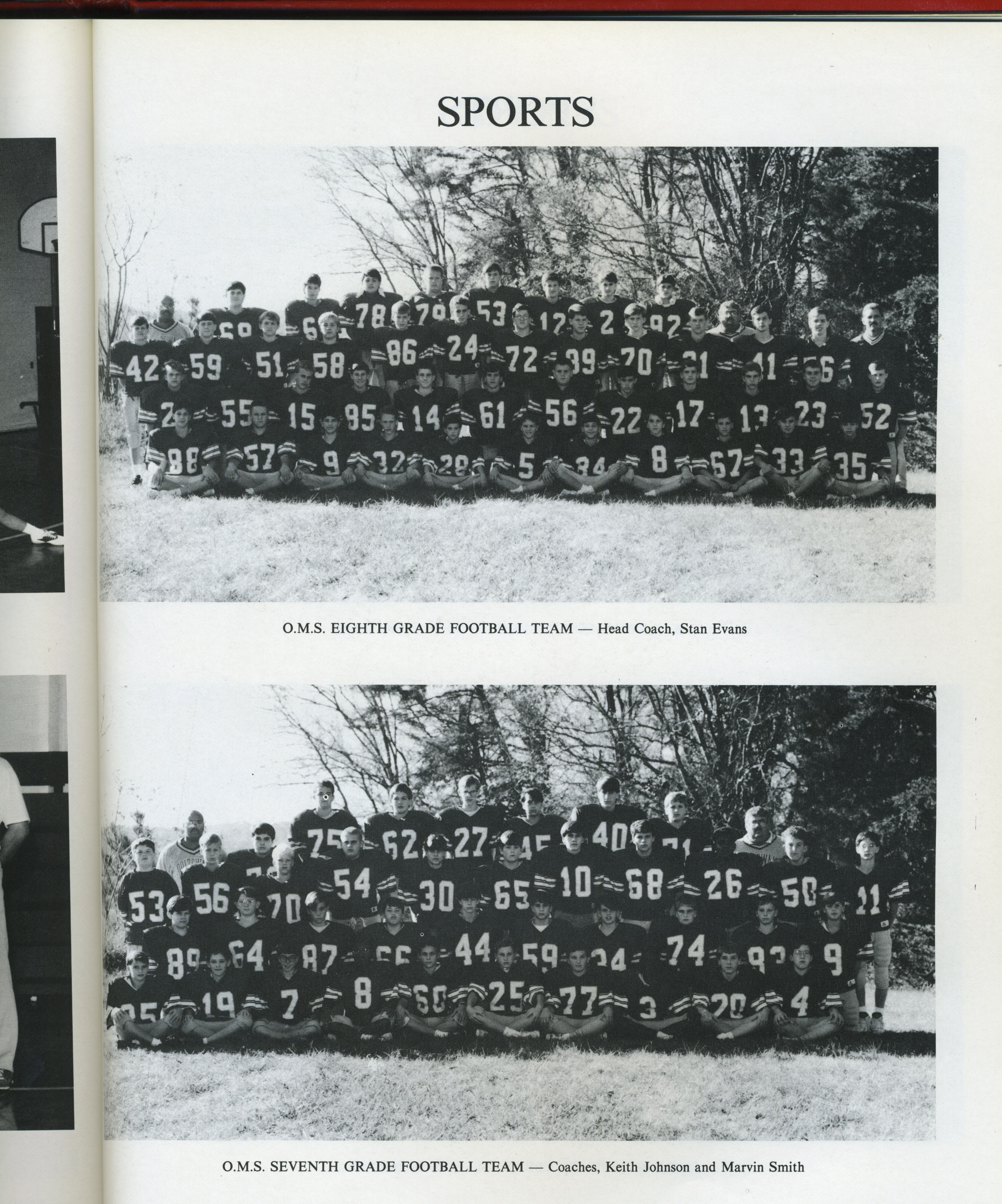

Mercer and other men claimed in the mid-1990s they and other boys were sexually molested by their coach, Stan Evans, at Ooltewah Middle School in the 1980s and ’90s.

In 1996, four years after Mercer graduated from Ooltewah High School, he warned school administrators about Evans, who remained at the middle school. Mercer said he was ignored. The following year, he took his complaints to police. In 2002, he and three others filed a lawsuit detailing the alleged abuse and what they said was the school system’s failure to act.

Evans, who resigned in 1998, was never charged. He has never spoken publicly about the claims. Attempts to reach him were unsuccessful.

But Mercer has not given up and continues to try to ensure Evans is not allowed around children.

“I can’t blame myself for the boys who were abused before me,” Mercer said. “But I hate that boys after me were hurt by him. It should’ve been stopped.”

Starting in 2001, complaints began to pile up against Ooltewah High teacher Jason Hamrick. Students and parents accused him of having inappropriate relationships with young male students. He taught at the school for nearly 15 years, despite more than a dozen complaints of misbehavior in his personnel file, including reprimands from Deputy Superintendent Robert Smith and then-Principal Ed Foster.

Like Evans, Hamrick was a coach. School leaders Rick Smith, Foster, Marvin Smith and Jarvis were also once coaches.

Ooltewah High School employees say coaches and athletes are elevated above everyone else. They complain coaches get promoted to assistant principal and principal positions over other teachers, while athletes get preferential treatment and avoid discipline.

“There are double standards,” said a school employee. “There are no rules in place, and everybody that isn’t a coach knows it.”

The athlete-first culture perpetuated by administrators permeates the school, numerous employees claim, protecting coaches like Evans and Hamrick from discipline.

Mercer and Ooltewah High teachers believe that if police in Gatlinburg, Tenn., hadn’t been alerted by hospital staff about the attack on the freshman player, news of the assault that night in a rented cabin would have never reached Chattanooga.

Despite the rape, Ooltewah High School teachers are fiercely loyal. Even those who speak out about the problems don’t want to leave, saying they love the community and are committed to the students.

Teachers also speak highly of their students, bragging of their accomplishments and character, saying it’s unfair to them that the school has been cast in such a negative light.

Students, too, have defended the school since the assault, making a video exemplifying positive characteristics of the student body and attending school board meetings to speak about the good things taking place there.

An Ooltewah High School football coach said that since the assault, school has continued on like normal, as if the incident is over.

“The actions of three people do not represent who we are as a school,” he said. “There are a lot of good people at [the] school. There are a lot of people that are going to make mistakes.”

Mercer said it was on Aug. 19, 1995, the night Mike Tyson made his return to professional boxing, that he realized Evans had been victimizing boys long before him.

As Mercer and his buddies watched Tyson fight Peter McNeely on television, he remembers one of his friends, a guy about six years older, leaning over and whispering, “He saw yours just like mine.”

Mercer graduated from Ooltewah High School in 1992. He said he and his friends never discussed during their school years what Evans did to them. Even after graduating, the boys never brought it up, and Mercer said he never let himself think about how many others could have been abused.

“There was a code of silence for us being abused,” Mercer told the Times Free Press. “We never talked about it.”

Mercer left that night and started contacting other guys he thought might be Evans’ victims.

“I then realized [Evans] was still at the school,” Mercer said. “… I lost my damn mind.”

Mercer said he tried for years to forget the abuse, leaning on alcohol to help relieve the pain. But knowing Evans was still around vulnerable young boys motivated him to speak up.

Mercer contacted another man, who also told the Times Free Press that Evans sexually abused him. Mercer convinced the man to try to help him get Evans fired.

The other man, who asked not to be identified, said the abuse started with Evans giving them attention, which slowly escalated to sleepovers and trips out of town with him.

Evans introduced the boys to alcohol, first Miller Lite and then Dos Dedos tequila, he remembers. Evans showed them pornographic films and rewarded them for touching themselves, and he never missed an opportunity to look at their bare bodies, he said.

Both men said Evans touched them, and at sleepovers he would choose his favorite boy to sleep in his bedroom while the other three or four boys stayed in the living room.

Evans always told them to keep “our little secret.” The men said they were embarrassed as boys to admit the abuse, and scared of what might happen if they told.

“To this day, it kills me to know this happened,” the man told the Times Free Press. “I will never forget or forgive this man for stealing my youth.”

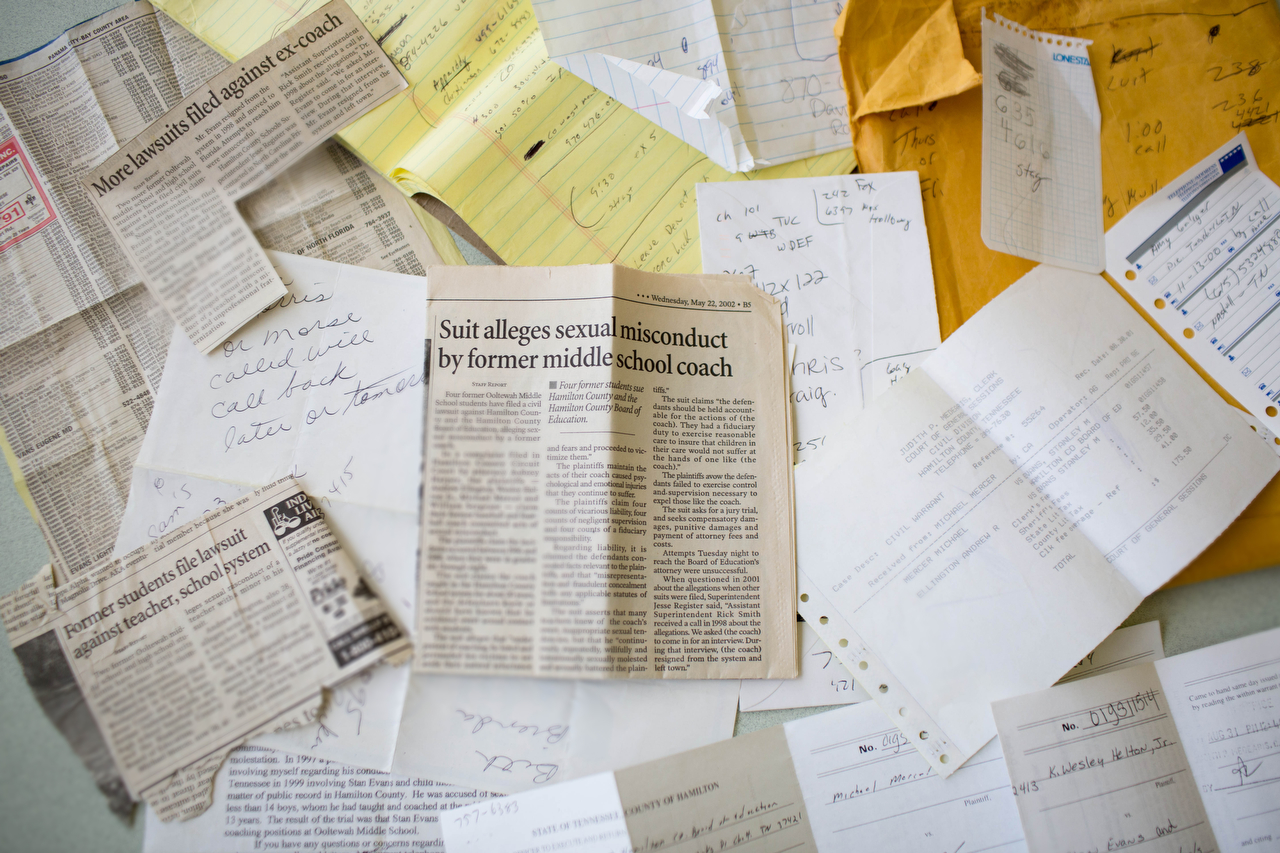

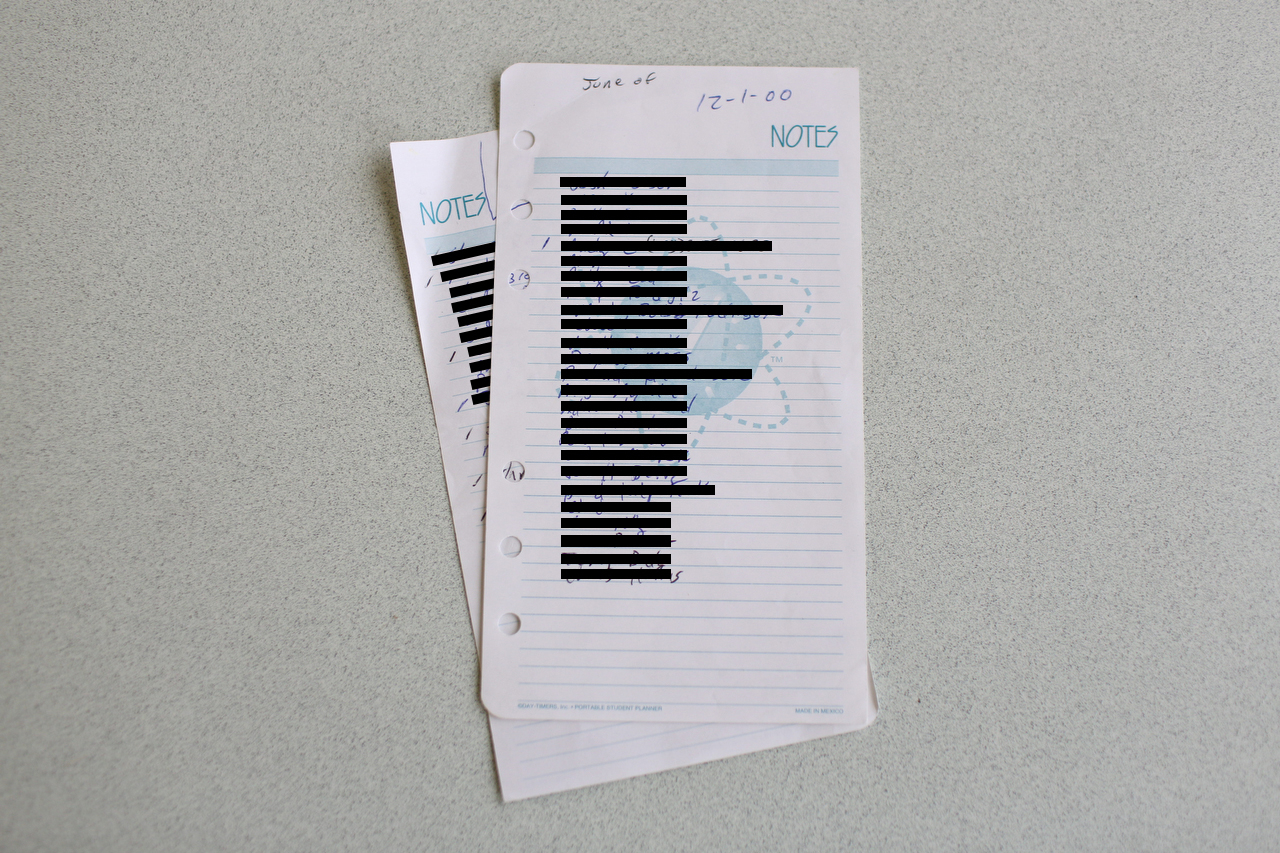

Mercer began keeping notes, covering the backs of old bills, fliers and notebook paper with names and numbers of people he thought might help. He kept dates of conversations and an ongoing list on a crumpled piece of paper of all the boys he believed Evans abused over the decades.

Thirty-eight names are now on the list.

By 1997, Mercer said, he was hounding school board members. He told then-Superintendent Jesse Register. He said he yelled over the phone at then-Middle School Director Rick Smith more than once, demanding he do something about Evans.

Mercer said he revealed the abuse to Marvin Smith, his middle school coach, who by then was assistant principal at Ooltewah High School, thinking Smith would for sure believe him.

Nothing happened. Evans remained at Ooltewah Middle School and was also promoted to a coaching position with the high school’s baseball team in 1997, according to the school yearbook.

Marvin Smith coached at the middle school with Evans in the late 1980s and early ’90s. Marvin Smith did not return multiple requests for comment for this story.

Mercer began to doubt if anyone would believe him or the others about Evans, who was one of everyone’s favorites — a teacher of the year in 1992 with a file full of glowing recommendations.

An evaluation from Evans’ first full year of teaching in 1980 said he was “of very high ethical character. He has developed and maintains a very good relationship with others.”

The evaluation gave him top marks for having good rapport with students, parents and staff, and demonstrating an ethical attitude.

The next year, Evans’ evaluation stated he dressed “extremely well” and spent “a great deal of his own time with students.”

On Sept. 9, 1997, Mercer went to the Hamilton County Sheriff’s Office and filed a report against Evans.

“Coach Stan Evans frequently had some athletes stay at his home. While at the home the coach showed the boys pornographic videos, gave them alcoholic beverages and forced the boys to expose themselves to himself,” the report states. “Mercer and other[s] never reported the incident due to the impact of embarrassment on themselves.”

The report says the incidents happened about 10 years earlier, meaning the cases were too old to prosecute.

“Efforts to contact Evans are pending,” the report stated.

Detectives asked Mercer to wear a wire and visit Evans in an attempt to elicit a confession, Mercer said.

He said he told Rick Smith what he was going to do, hoping Smith would take the claims seriously. Still, nothing appeared in Evans’ personnel file until nearly a year later. He continued teaching and coaching.

Rick Smith told the Times Free Press Mercer did not call him until a few days before Evans resigned.

Records show that days before Rick Smith said he received this call, Register placed Evans on administrative leave with pay “due to a legal matter about which you will be expected to keep both my office and the personnel office apprised through the resolution of the matter,” according to a letter in his file dated Aug. 17, 1998.

Register, now retired, told the Times Free Press he can’t put a date on when he was first told about Evans, but it was sometime before Evans submitted his resignation.

“I knew there was a concern expressed,” Register said. “But these were adults who were complaining about things that had happened much earlier.”

He said Rick Smith, who was the director of middle schools at the time, started to investigate the allegations. Register remembers concern about continuing problems with Evans, but said the district couldn’t prove anything.

Rick Smith said he had no knowledge of any concerns about Stan Evans until he got the phone call from Mercer. He said after receiving this phone call he contacted two detectives at the sheriff's office, and after Evans resigned a few days later he was no longer involved in the situation.

Weeks later on Aug. 31, the sheriff’s office filed another report.

The report reiterates the statute of limitations had expired in Mercer’s case, but “despite this limitation the victim and witnesses all stated with corroborative events of the ongoing sexual perversions, the inappropriate actions, comments, and unprofessional fraternization by coach Evans.”

The report also says statements from an unidentified pastor had given the sheriff’s office reason to reopen the case.

On Sept. 3, Evans scribbled a handwritten note stating he planned to resign from Hamilton County Schools for “personal reasons,” effective Sept. 14.

“I intend to remain on sick leave through 9/11/98,” the letter states.

The sheriff’s office closed the case on Sept. 23, 1998, and noted that Evans had resigned from the school.

After Evans left, several teachers told Mercer and the other anonymous victim they had suspicions about the former coach.

The anonymous victim said he told current Ooltewah Principal Jim Jarvis about Evans in 2000. He said Jarvis admitted to having suspicions about Evans, but said he had never told anyone.

“[Jarvis] seemed like a really nice guy and wanted to help, but said he knew something about it back in the ’80s,” the man said.

Jarvis did not respond to multiple requests for comment for this story.

After the resignation, the Hamilton County Department of Education did not contact the Tennessee Department of Education to flag Evans’ teaching license until Nov. 16, 2000, more than two years later.

Assistant Superintendent Lonita Davidson wrote: “Based on the information that the Superintendent has received today concerning Mr. Evans, there are allegations concerning improprieties as they relate to child molestation.”

Davidson’s letter said Evans’ teaching license was still on file because he did not request it be returned after resigning.

“Based on the information the Superintendent received this morning, I would suggest flagging his teacher’s license until the allegations are proved or disproved,” the letter stated.

A separate letter in Evans’ personnel file from the Tennessee State Board of Education dated July 29, 2001, said the board was planning to deny his application for a teaching license due to pending civil charges of sexual misconduct with minors.

Mercer said he tracked Evans to Panama City, Fla., and he and the anonymous victim drove down in 2000 to find their former coach.

The two said they hung fliers up all over Evans’ neighborhood bearing a picture of his face and stating he was a child molester. The fliers listed Evans’ address and gave Mercer’s phone number to call for more information. They visited local churches, YMCAs, day cares and police stations, warning them Evans lived in the area.

Mercer said police warned him he could be charged with stalking, and he told them he hoped Evans would file a complaint because the two could finally go to court, which is what he wanted.

But Evans never filed a complaint, Mercer said, even after he punched his former coach in the face.

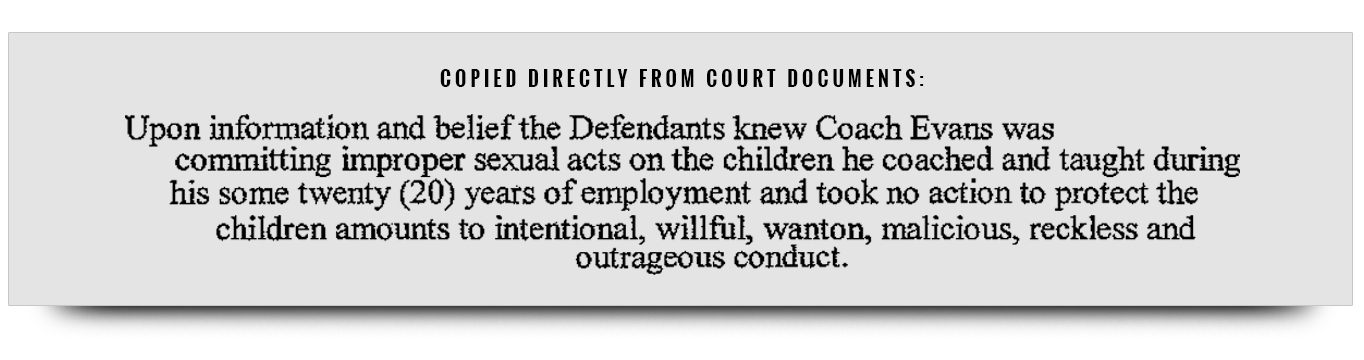

In 2002, Mercer and four other men filed a lawsuit against Hamilton County and the Hamilton County Department of Education claiming Evans sexually abused them.

“Coach Evans used his authority as a teacher and coach to extort compliance from the minors and continued his molestation of these Plaintiffs for many years for his own sexual gratification,” the lawsuit stated. “Under the pretext of coaching he lured and persuaded his victims to set aside their natural reluctance and fears and proceeded to victimize them.”

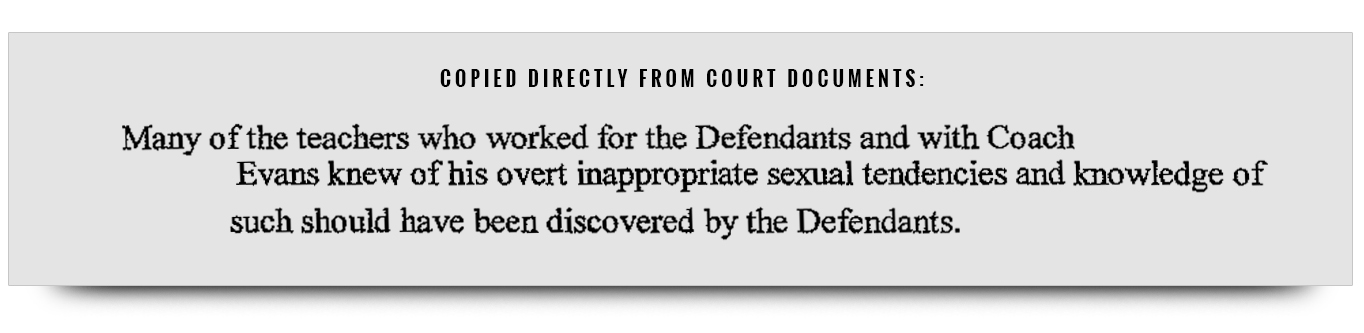

The lawsuit claimed the school system knew or should have known Evans exhibited overt sexual contact with many students.

Mercer and the anonymous victim, also a plaintiff, said Evans’ affection to them and other boys was often public. He would kiss them on the cheek in the gym, grab their bottoms and exchange shoulder rubs with them.

Former teachers and parents told the Times Free Press they remember Evans’ actions and found them strange.

“Many teachers and principals observed these activities and were uncomfortable with them,” the lawsuit stated. “However, no one ever stepped up and confronted ‘Coach Evans’ and no investigation was ever conducted to find out whether the suspicions and rumors about ‘Coach Evans’ and his inappropriate conduct was with or without merit.”

The victims’ mothers joined the suit in July 2002, saying the school system breached its duty to protect their children.

The mothers claimed an implied contract with the school system to keep their children “safe, free and clear of sexual assaults, especially from a teacher and coach like ‘Coach Evans’ who owed a duty to provided a safe haven for the children in his charge.”

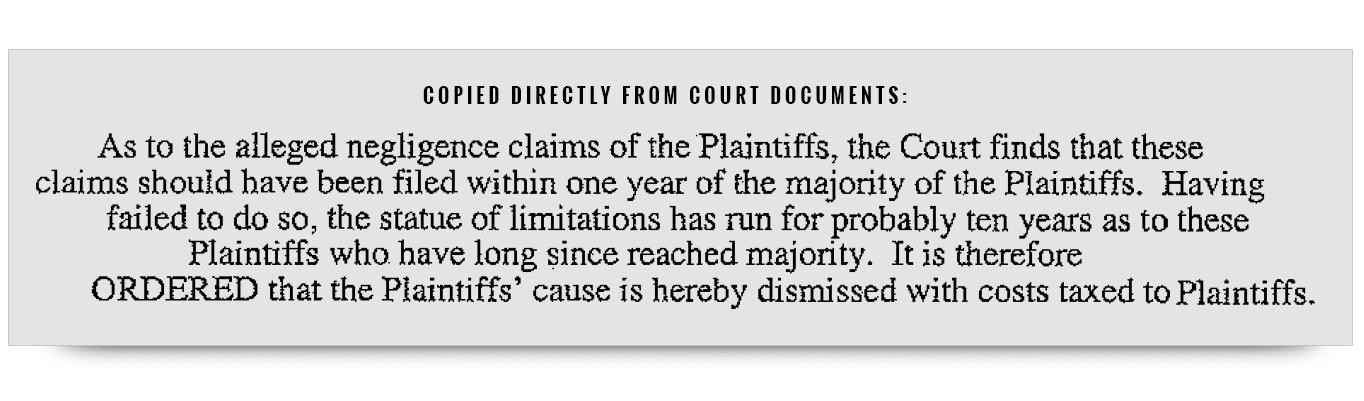

The lawsuit was dismissed in January 2003 by Circuit Court Judge Jacqueline Schulten for multiple reasons, including that the statute of limitations expired when the boys turned 19, according to court records.

School board attorney Scott Bennett defended the board in this case, and said after the first lawsuit was filed he and a team of at least three people went to Ooltewah Middle School and interviewed faculty.

“We were unable to corroborate the claims that teachers knew or should have known of Evans’ alleged misconduct,” Bennett said.

Today, as Mercer leafs through police reports and court documents and his envelopes full of notes from the past 18 years, he gets angry all over again.

But now, at least, Mercer has come to a place where he can laugh at home with his wife of five years. He jokes that he loves her because she’ll sit on the couch with him and watch “Rocky” for the thirty-seventh time. He swears he can quote every line.

His wife, Angie Mercer, said he makes the best sandwiches and always tries to spoil her.

And under the neon lights of Mercer’s favorite bar he cracks jokes and greets friends with a hug. He says he finds peace knowing he is doing what he can to save kids from the past he endured.

Still, not a day passes that he doesn’t think about Evans.

“I just don’t ever want to see anyone else be hurt,” he said. “I’ll do whatever I can to stop it.”

A year after Evans left Ooltewah in 1999, Jason Hamrick began teaching and coaching high school basketball there. Over his nearly 15-year career at the school, his personnel file filled with complaints.

He was first reprimanded in February 2001 by Assistant Superintendent Davidson for making students buy basketball season passes or do manual labor at his house in exchange for grades.

Administrators told Hamrick his actions could be interpreted as extortion. He apologized.

“You need to consider the impact of your actions had a parent or the community heard about your behavior and the damage it could have caused the schools and your personal career,” then-Principal Ed Foster wrote in his file.

Later that year, a parent wrote a four-page letter to Foster complaining about Hamrick’s coaching style. Instead of taking disciplinary action, Foster recommended Hamrick for tenure, according to the file, and the school board approved it in 2002.

"Consider the impact of your actions had a parent or the community heard about your behavior..."

In February 2003, another parent complained that Hamrick made inappropriate comments to students — talking about beer and women — and used vulgar language. A report Hamilton County filed with the state says Hamrick made a student-athlete get out of a car and run a mile on a busy highway, according to his personnel file.

Hamrick was removed from all coaching responsibilities in May of 2003, his file states. However, yearbooks from 2006 and 2013 show he was still coaching the cross-country team.

Complaints continued to pile up, and he received a reprimand in May from Deputy Superintendent Robert Smith for sleeping in a hotel room with three male students while chaperoning a school trip.

“I can’t defend my actions during the trip,” Hamrick told administrators.

But the allegations kept coming. In October 2007, a message sent to Ooltewah High School stated, “You have a child molster [sic] on your staff,” according to a memo in his file.

This prompted an investigation by the Hamilton County Sheriff’s Office. A boy stated he slept overnight at Hamrick’s house when Hamrick was his youth minister, before he started teaching at Ooltewah.

The boy said Hamrick talked to him about masturbating and touched his penis, records show.

No charges were filed. Weeks later, Foster met with Hamrick and told him not to supervise students alone or talk to them in the hallway or common area except for routine greetings, according to Hamrick’s file.

“For whatever reason, you simply do not recognize when you have crossed the line between your desire to be a compassionate teacher and the perception that you are cultivating an unhealthy relationship with young boys,” Foster wrote.

In April 2008, Foster reprimanded Hamrick yet again.

In a three-page letter, the principal said students were uncomfortable with Hamrick’s personal questions and described him as “creepy.” Hamrick acknowledged he had been confronted by administrators “too many times,” according to his personnel file.

Foster retired in 2009, and Mark Bean took over as principal at Ooltewah High School. Afterward, no complaints appeared in Hamrick’s personnel file until the beginning of 2014.

On Feb. 26, 2014, two 11th-grade students gave statements. One said he spent the night at Hamrick’s house “around 20 times” during his ninth-grade year. The other said he had been paid for doing manual labor at Hamrick’s home.

"You simply do not recognize when you have crossed the line..."

The next day, the school district’s director of human resources interviewed Hamrick. Before the meeting ended, Hamrick wrote his a resignation on a legal pad.

School district officials told the Times Free Press in 2014 they had learned only recently of the claims, as the issues in his school-level file were not sent to the central office file.

But at least two complaints in Hamrick’s file were drafted by central office staff: one by Assistant Superintendent Davidson in 2001 and one by Deputy Superintendent Robert Smith in 2003.

On Thursday, Foster told the Times Free Press the central office people in charge of personnel definitely knew about the complaints in Hamrick’s file. Foster said officials came to the school numerous times to talk to Hamrick.

“If there was any kind of incident, a negative incident or accusation, it was turned over to the personnel department at central office,” Foster said.

Rick Smith was serving as Deputy Superintendent and Superintendent through a majority of Hamrick’s tenure. He said he wasn’t told about the complaints in Hamrick’s file, and when it was brought to his attention he acted promptly.

“On my watch he resigned,” Rick Smith said.

Jarvis, now Ooltewah’s principal, was assistant principal and athletic director from 2000 to 2013, nearly the entire time Hamrick taught and coached at the school.

Hamrick did not respond to requests for comment. According to the state’s licensing website, his teaching license is still active.

After Hamrick resigned, Dannelle Walker, general counsel for the Tennessee Board of Education, told the Times Free Press there was not enough evidence to defend a suspension or revoke Hamrick’s license if the case went to court. She also stated Hamrick had previously been cited for insubordination.

“We felt like Mr. Hamrick still had the ability for rehabilitation and that a reprimand would send that message,” Walker said.

An Ooltewah teacher said it is uncommon for teachers to have even one or two write-ups in their files, and this many offenses without disciplinary action is “completely unheard of.”

Another teacher who worked with Hamrick said he never noticed anything inappropriate in his behavior, unlike that of Evans.

“Now that the docs from [Hamrick’s] personnel file are public I can’t believe that people knew and nothing was done about it,” the teacher said. “People that were in a position to do something did nothing.”

H amilton County investigators believe the screams of the 15-year-old on Dec. 22 were not the first time Ooltewah High School’s basketball coaches were alerted to the team’s misbehavior.

They believe the younger players endured abuse before the trip. It was a part of the team’s “beat-in” culture, and it was routine for freshmen to be hazed and possibly assaulted.

One freshman player told his mom the older boys said, “This is what you do to freshman; y’all will be doing it, too, one day.”

What may have started as hazing in the locker room and showers escalated to older players punching, kicking and striking the boys with pool cues during the Gatlinburg trip, mothers of two freshman players told the Times Free Press.

They will not be named to protect their sons’ identities.

Then the hazing turned to violent assault.

“Four freshmen basketball players were subjected to assaultive behavior, including but not limited to being struck with pool cues and also these four freshman basketball players were subjected to apparent sexual assault,” Mickey Roundtree, a detective with the Hamilton County Sheriff’s Office, wrote in an affidavit.

Officials said the Hamilton County District Attorney’s Office received a report that the coaches left the boys unchaperoned at the Gatlinburg cabin while they went grocery shopping for several hours.

The day of the assault, Ooltewah played Lebanon High School in the Smoky Mountain Classic basketball tournament. Lebanon head coach Jim McDowell previously told the Times Free Press that Ooltewah was more troublesome than any team his team had played all season.

During the game, one of the boys now charged in the rape case threatened to shoot one of Lebanon’s players, McDowell said.

After losing the game 74-60, several Ooltewah players were unsupervised in the parking lot and verbally harassed Lebanon’s players in what McDowell called a “volatile situation.”

Family members of the 15-year-old victim told the Times Free Press the boy had reported his teammates’ abuse to the coaches, and that the older boys retaliated that night.

Hearing the boy’s screams, the coaches rushed to the basement bedroom to find him lying on the floor in a pool of blood, urine and feces, according to the Hamilton County District Attorney’s Office.

The victim’s family declined to comment for this story due to upcoming litigation.

The coaches didn’t call police or the Department of Children’s Services, as required by law. They took the boy to LeConte Medical Center, where medical staff alerted the proper authorities, according to the Gatlinburg Police Department.

The 15-year-old was released from the hospital and taken back to the cabin where the three teammates who allegedly raped him were still staying. Before the next morning, the three boys suspected of the assault were taken back to Chattanooga, according to a source close to the incident who asked to remain anonymous.

Hours later, the injured teen was taken to the University of Tennessee Medical Center in Knoxville, where surgeons repaired his colon, bladder and prostate, according to court records.

"This is what you do to freshman; y’all will be doing it, too, one day."

As their teammate lay in a hospital bed, the basketball team played its final tournament game before returning home. The team played three more games before Superintendent Rick Smith canceled the team’s season Jan. 6, nearly two weeks after the incident.

The three boys are charged with aggravated rape and aggravated assault, and are scheduled to appear before Sevier County Juvenile Court Judge Dwight Stokes on March 15.

Hamilton County District Attorney Neal Pinkston filed charges on Jan. 14 against Ooltewah head coach Andre “Tank” Montgomery, assistant coach Karl Williams and Athletic Director Allard “Jesse” Nayadley for failing to report child abuse or suspected child abuse.

Pinkston has subpoenaed Rick Smith, Jarvis, Assistant Superintendent Lee McDade and Secondary Operations Director Steve Holmes. They are expected to testify Monday about what information they received and when and how they responded.

Nearly a dozen current and former employees and students at Ooltewah High School said athletics rule the school, and both coaches and athletes receive preferential treatment.

Employees gave example after example of athletes not receiving the same discipline as their classmates, and not having to abide by the rules that require a dress code and prohibit wandering the halls. They say there is a disrespect for authority among many athletes, especially the boys.

“It’s created this atmosphere where athletes can do whatever they want,” one employee said. “It is out of control.”

The employee said one of the boys charged with the rape previously yelled and cursed at him/her at the school. The employee reported the incident, but said administrators didn’t believe him/her, saying the athlete would not act that way.

Ooltewah High School also has been accused of recruiting athletes from across the district by using hardship transfers, which allow students to travel to schools outside of their zones.

According to Department of Education records, Ooltewah High School has the most hardship transfers this year, accepting 101 students. East Hamilton High School is second, with 87, and Red Bank High School was third, with 50.

McDade said the district does not track which students receiving hardship transfers are athletes.

"It’s created this atmosphere where athletes can do whatever they want."

Personnel files show Ooltewah coaches are often promoted to be assistant principals and then principals.

Though this is not unique to Ooltewah, teachers say it has created a “good old boy” system, where coaches and administrators look out for and promote each other.

“It seems like there is a trend, if you coach anything you’re able to move up into administration, and upper-level administration,” said Sandy Hughes, former president of the Hamilton County Education Association for six years. “If you want to move up in administration, you better find something you can coach.”

Hughes, who has been in the school district since 1991, said she has noticed administrators at many schools, including Ooltewah High School, act as if sports are the most important thing.

“The focus is lost, especially if students or teachers see that athletes get preferential treatment,” Hughes said. “It devalues education.”

Jarvis came up as a coach and assistant principal. So did his predecessor, Bean, and the principal before him, Foster, according to Times Free Press archives and Hamilton County Department of Education personnel files.

Marvin Smith, the retired coach and principal, also came up through the Ooltewah pipeline. Called in to help following the rape, he is now working in an administrative role at Ooltewah High.

He began his career as a coach at the middle school during the time Evans was there, then became assistant principal at the high school in 1993, according to his personnel file.

Donald Mullins, another Ooltewah teacher and coach, was promoted to help with administrative duties during Nayadley’s suspension. According to the state’s licensing website, Mullins does not have an administrative license, although a handful of Ooltewah High teachers do.

Nayadley coached the boy’s basketball team at Ooltewah High before he was named athletic director, and it was widely rumored before the assault that he was likely to replace Jarvis when the principal retired.

The school does have two female assistant principals who were not coaches, which Hughes said is a positive thing.

Drew Herrmann said classmates cheered in September 2011 as Hunter Middle School’s star football player whipped him with a leather belt in the locker room. Herrmann and his classmates were changing after gym class when two boys held him upside down by his ankles while the third beat him.

A Hamilton County Sheriff’s report documents the attack, saying three boys assaulted Herrmann and three others while another classmate videoed the whippings.

The assault happened at the beginning of Herrmann’s eighth-grade year at Hunter, which feeds into Ooltewah High School.

According to the sheriff’s report, the boy who whipped Herrmann and the other boys “giggled about the event and said he was just having fun.”

The boy also told investigators no one would tell on him because “people respect me and who I am, so I can do what I want,” the report states.

The three boys were each charged with three counts of aggravated assault and false imprisonment, according to the report. Additional information in the case is sealed because they were juveniles at the time.

Herrmann, now a senior at STEM School Chattanooga, said he did not talk about what happened for the rest of the day after the assault because he was humiliated. His mom, Tracy Sims, said she knew something was wrong as soon as she picked him up that day. As they were driving home, he blurted out what happened.

“I was terrified it’d get worse if I didn’t tell,” Herrmann said. “I didn’t want another kid to get hurt.”

After Herrmann and his mom told authorities and the school what the boys did, Herrmann said he was even more afraid to go to school. He lived in terror every day, worried about retaliation for getting football players suspended.

He remembers walking down the hallway and having students blame him for the football team’s losses.

Sims still carries guilt for assuming the school would protect her son and make him feel safe.

“When you send your kid to school you go in and answer all of these questions, telling them about your kid’s shots and where you live,” Sims said. “Do we need to start going in and saying what are your policies? How will you keep him safe?”

Hearing about the Ooltewah assault, Sims said she was devastated to know the school system did not learn from previous mistakes and do more to protect students.

After her son was attacked, Sims said she tried to convince the school district to put in place stronger anti-bullying programs.

“Nothing happened,” she said. “What has to happen next? Someone has to die?”

Since the rape, the Hamilton County community has called for change. School board meetings have been packed. Community support around improving school is solidifying and parents and students are talking more openly about hazing and bullying.

Some school board members say it’s time for serious action, and on Thursday the board agreed to consider an outside audit of school culture districtwide.

Next week, the school board is expected to discuss Rick Smith’s departure. He asked for a buyout after he was criticized for not speaking publicly about the rape for 20 days.

Some in the community say these are the first steps toward improvement.

And now teachers, parents, elected officials and students are waiting to see if the lessons of this rape could result in lasting change.