A night

in the hospital,

A rape case,

a mystery

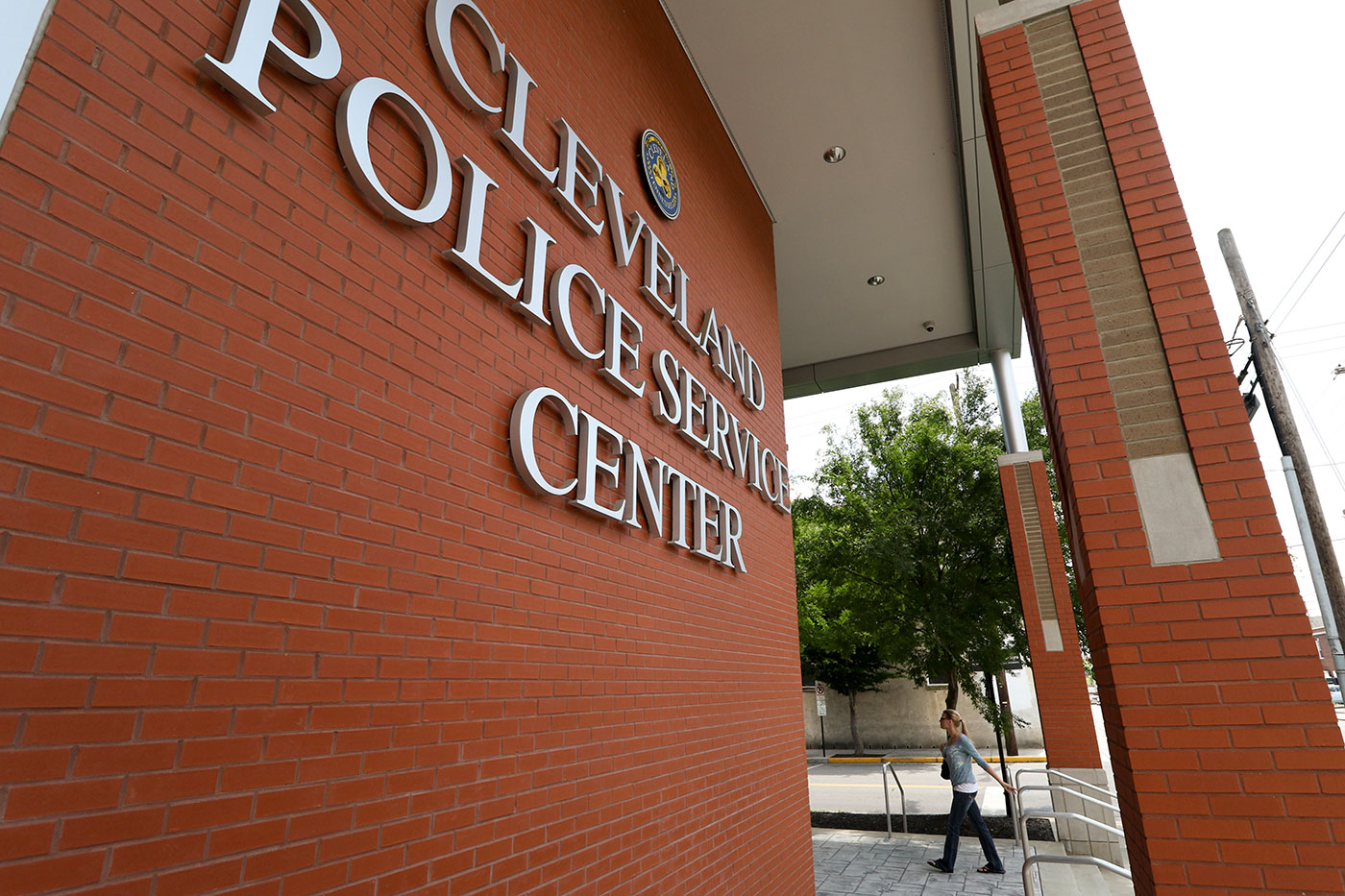

Stacey Cordell rocks herself in front of a local clothing store after confronting the Cleveland Police about her rape case. Stacey reported to the police in January that she was raped while she was unconscious in the emergency room.

A night in

the hospital,

A rape case, a mystery

Stacey Cordell jolted awake from the nightmare when her 8-week-old pit bull gently nipped her cheek.

Her T-shirt and sheets were wet, again, and she could barely catch her breath. She tried not to wake her husband as she climbed out of bed. The puppy scurried ahead, out the door.

These nights, two hours of sleep was typical. She needed more. She wanted more. But once the images came back, her body had its own agenda. The adrenaline told her to be alert. The fear told her she still wasn’t safe.

After all, it was sleep that had made her so vulnerable those months ago, and many evenings it’s sleep that takes her back to that night.

It always starts the same way.

Stacey is lying in a hospital bed, shivering. Then the door opens and she turns. He’s there again, scowling as he walks toward her. Don’t get out of bed, he insists, stopping a foot away, peering down at her body, which is covered by only a thin hospital garment. She wants to scream, but she can’t. The room goes gray, then black.

Then she sees the faces of police, the same stony expressions. Sometimes in the dream she’ll get angry and scream. Sometimes she just whimpers. But the expressions never change.

That early morning, while the puppy sniffed through the grass, she was enveloped by the hopelessness the dream always triggered. No one wanted to believe her story, she thought. No one wanted to investigate or care.

Still, it didn’t matter, she reminded herself. She would make them.

Today she would tell them they had to listen. Today she would tell them that they were wrong. She knows something happened to her that January night when no one was looking.

She knows she is not a liar.

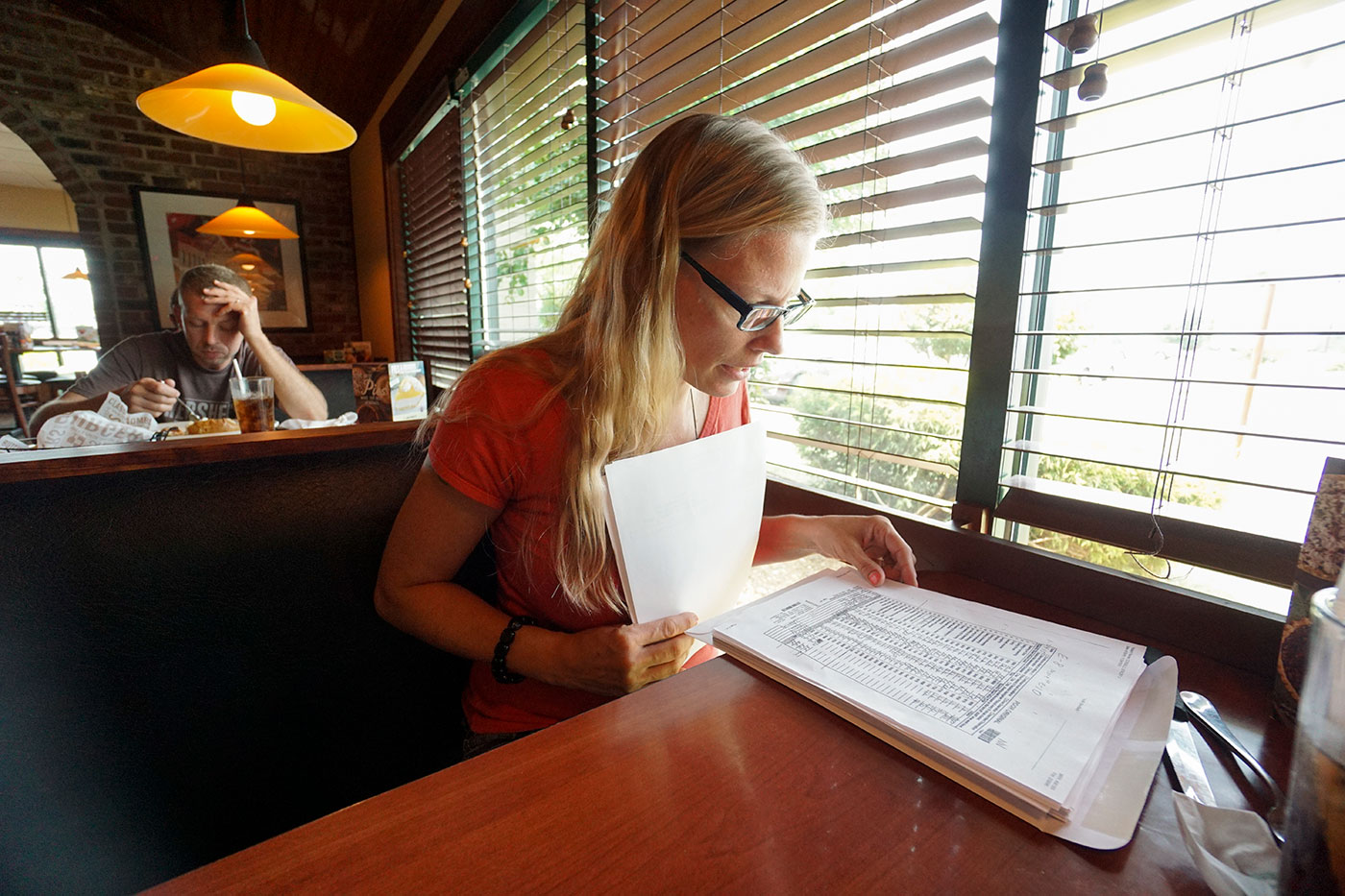

Stacey Cordell stares off into the distance while eating lunch at O’Charley’s. Stacey says she often feels hopeless because no one in authority seems to take her report of rape seriously.

Rape is unlike other crimes.

When a person is found dead, when a purse is stolen, when an eye is bruised and swollen, the act is the evidence.

But the act of sex isn’t usually sinister. It’s often mutual.

Still, sometimes it’s not. Sometimes it’s a brutal violation, a trauma that never goes away.

And when that happens it becomes a question of memory, of intention, of what was spoken and unspoken. And the persons who claim to be the victim often finds themselves as scrutinized as the accused.

If there weren’t bruises, then did she fight back? If the victim changed any of her story, did she tell the truth to begin with?

2% to 10%

ESTIMATED PERCENTAGE OF RAPE ALLEGATIONS THAT ARE FALSE.

Even though research shows that the brain stores memories differently under stress, police often rely on outdated interviewing techniques to question rape victims, making the cases even muddier.

And this back and forth, this dance to determine whether a crime happened at all, often leaves these cases unresolved altogether.

It is true that some reports of rape are later discredited. Rolling Stone featured the story of a woman, who claimed she was gang raped at the University of Virginia, but the article has since been harshly questioned and retracted. A high school football starter in California was exonerated after spending five years in prison when his accuser admitted she had made up the story. In 2009, a New York man was exonerated after 20 years in prison for the rape of his friend, who later said she she lied about being assaulted to cover up a fight with several women.

Yet research accepted by women’s advocates and the FBI show false accusations are fairly rare. The percent of rape cases categorized as “unfounded” by the FBI hovers around 8 percent, but those cases include more than outright false accusations. A detective might deem a rape “unfounded” even if a women tells a truthful story about a sexual encounter but the officer thinks the encounter was consensual.

A well-regarded study that examined other research on false allegations of rape and reviewed 10 years of accusations at Northwestern University concluded that only between 2 percent and 10 percent of rape victims are being dishonest. Even so, many cases that find themselves in the hands of a detective don’t result in prosecution.

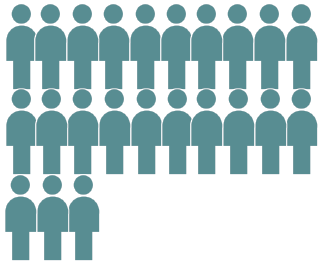

A low rate of conviction

The majority of reported rapes to the police don’t end in a guilty verdict. Here are the numbers for 10 years in Hamilton and Bradley counties:

1,725 rapes reported

353 arrests made

76 found guilty of rape

Source: Hamilton and Bradley County court and police records.

Less than 5 percent of the 1,237 reported rapes in Hamilton County in the last 10 years ended in an actual rape conviction. And experts say there are many more rapes that are never even brought to police.

In Cleveland, where Stacey said she was raped, it’s also the case. Of the 488 reported rapes in Bradley County over the last decade less than 4 percent of cases ended with a rape conviction.

Stacey Cordell stares off into the distance while eating lunch at O’Charley’s. Stacey says she often often feels hopeless because no one in authority seems to take her report of rape seriously.

2% to 10%

Estimated percentage of rape allegations that are false.