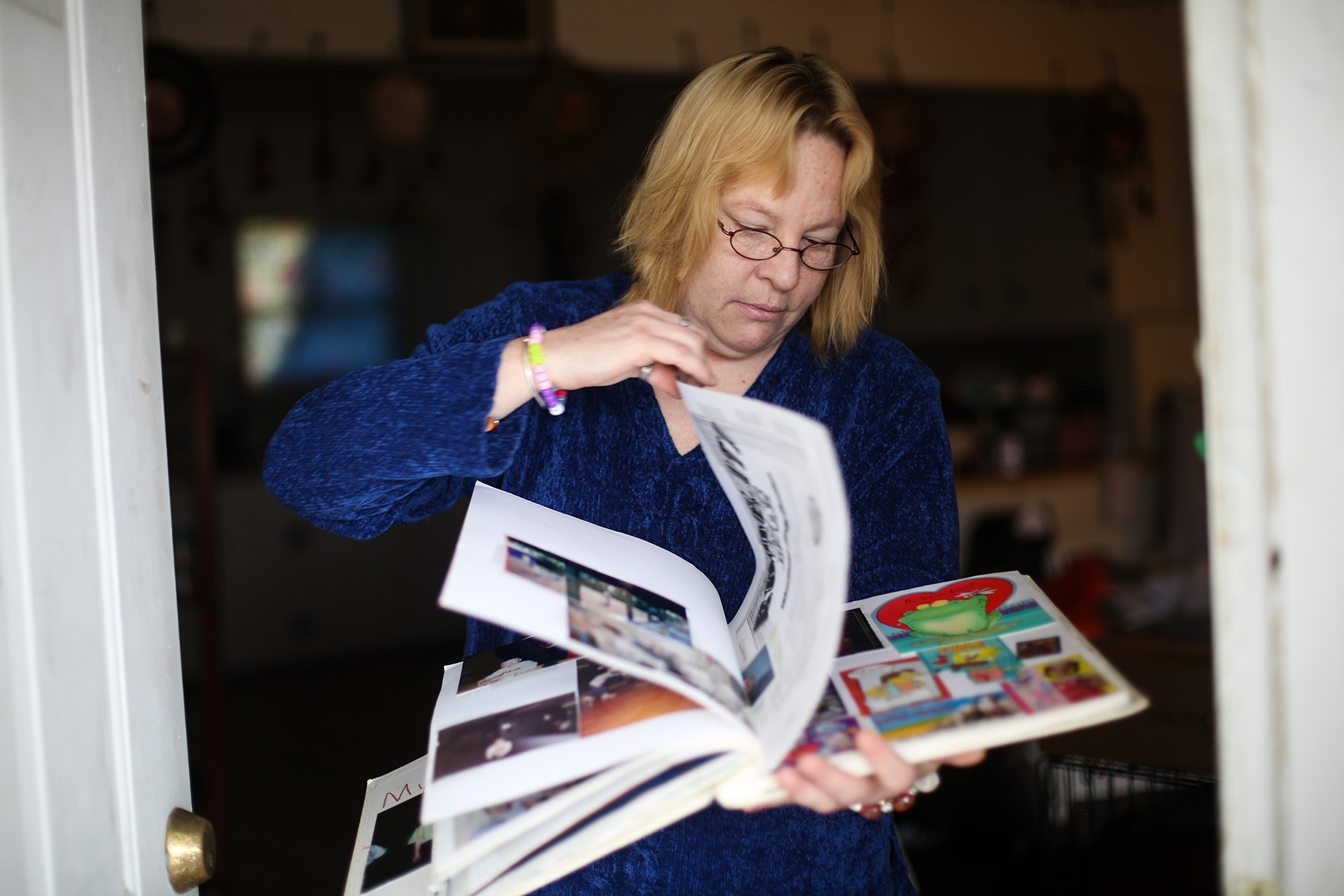

The same psychologist who found fault with the state’s investigation heaped numerous new mental illness diagnoses on McBryar and Multari.

At 8 years old McBryar had been diagnosed with ADD and began to take Adderall. In high school, he often skipped classes to smoke pot and he found it difficult to pay attention. He went to three psychologists convinced something else was wrong. But each professional told him he was on the right treatment for his condition.

But the psychologist hired by the state to assess McBryar diagnosed him with five new mental illnesses after a two-hour interview and a few tests. She said he had an alcohol use disorder, an antisocial personality disorder, an intermittent explosive disorder, a borderline personality disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Her evaluation also made assumptions about his past and predictions about his future.

McBryar is “unusually energetic” which most likely means he meets a diagnostic criteria for a manic or hypo-manic episode, the report stated. And because McBryar has a history of antisocial behavior, “he may have been involved in illegal occupations or engaged in criminal acts,” she wrote, citing that he had once been suspended from school as a teenager for fighting.

On the other hand, Multari was faulted for having the expectation that her children should be obedient. The psychologist suggested that she had rigid and OCD tendencies that could escalate into child abuse.

“If not modified, these traits can result in abusive interactions with children,” the report stated.

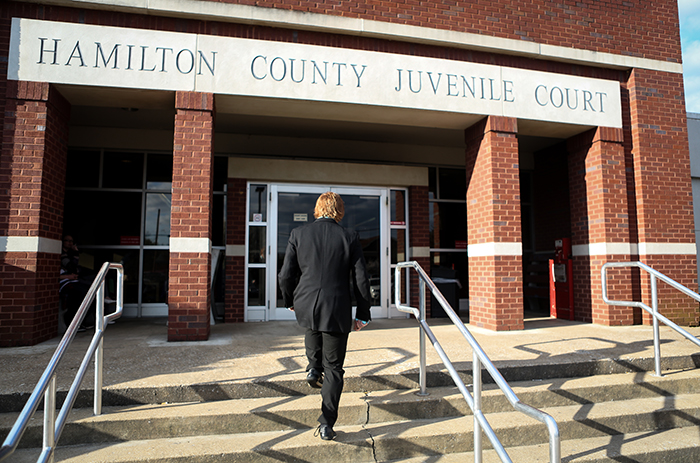

It seems strange that a person could face charges of child abuse or neglect when neither has occurred, but it happens all the time under a concept some states call “predictive neglect.” Some courts allow states to decide if a parent is unfit based on the potential threat a parent might pose with a mental illness. In Georgia, the parental rights of couples who have never abused their children can be terminated if a court determines the children are “without proper parental care and control,” meaning that a parent’s physical, mental or emotional state could lead to abuse or neglect in the future.

Still, caseworkers don’t just assume a mentally ill person will neglect or abuse their child based on a hunch. The prediction of risk must be made by a mental health professional, said Susan Boatwright, a spokesperson for DFCS.

And tests, not home visits, are standard practice in determining a parent’s likelihood of abuse, despite experts’ concern over the weight these tests are given.

“The tests likely were not developed nor really, originally, meant to be used in this way―which makes the procedure invalid,” said Joanne Nicholson, a professor at Dartmouth Psychiatric Research Center.

In fact, the American Psychological Association advises courts and professionals not to rely solely on tests and urges officials to also spend time with the family being assessed.

Still, to Murray County Judge Connie Blaylock, Multari and McBryar’s test results were enough for her to determine they weren’t ready to raise their daughter.

They said Blaylock ordered Multari to take weekly therapy for her OCD tendencies and ordered McBryar to check into a 30-day inpatient mental facility for treatment.

This, along with a $432 monthly child support payment, was added to the couple’s lengthy list of requirements.

Diana and Will's monthly budget

$1,560

Income if Diana works full time

$350 for rent

$240 for gas

$55 for phone

$180 for car insurance

$100 for Will's child support

$332 for Diana's child support

$303

Is the amount of money they have left

It seemed impossible, they told each other. How could they hold a job if they were required to do inpatient treatments and continue visits with Tobi and attend court? How could they pay for child support if McBryar didn’t have work? How could they afford a larger apartment if their money was tied up in child support?

And the law said this all had to be done in four months. They asked the state for more time because the state had delayed their case, but the caseworkers blamed them for the delays.

If progress wasn’t made by June, the process of terminating their parental rights could begin.