They bought the house at the end of a cul-de-sac with the children in mind.

They imagined the tan-skinned babies running through a sprinkler in the sticky summer, racing tricycles with cut-up knees, their cheeks spotted with peanut butter and jelly.

They painted the walls in two small rooms. Black and orange for the little boys. Mint green for the girl. They pasted stickers of motorcycles and butterflies. They bought a rubber ducky for the bathtub.

And they promised each other that they would give the children all they could, kisses after bedtime stories and toys to unwrap on Christmas morning and warm arms when the past, the nightmares, crept into their little minds.

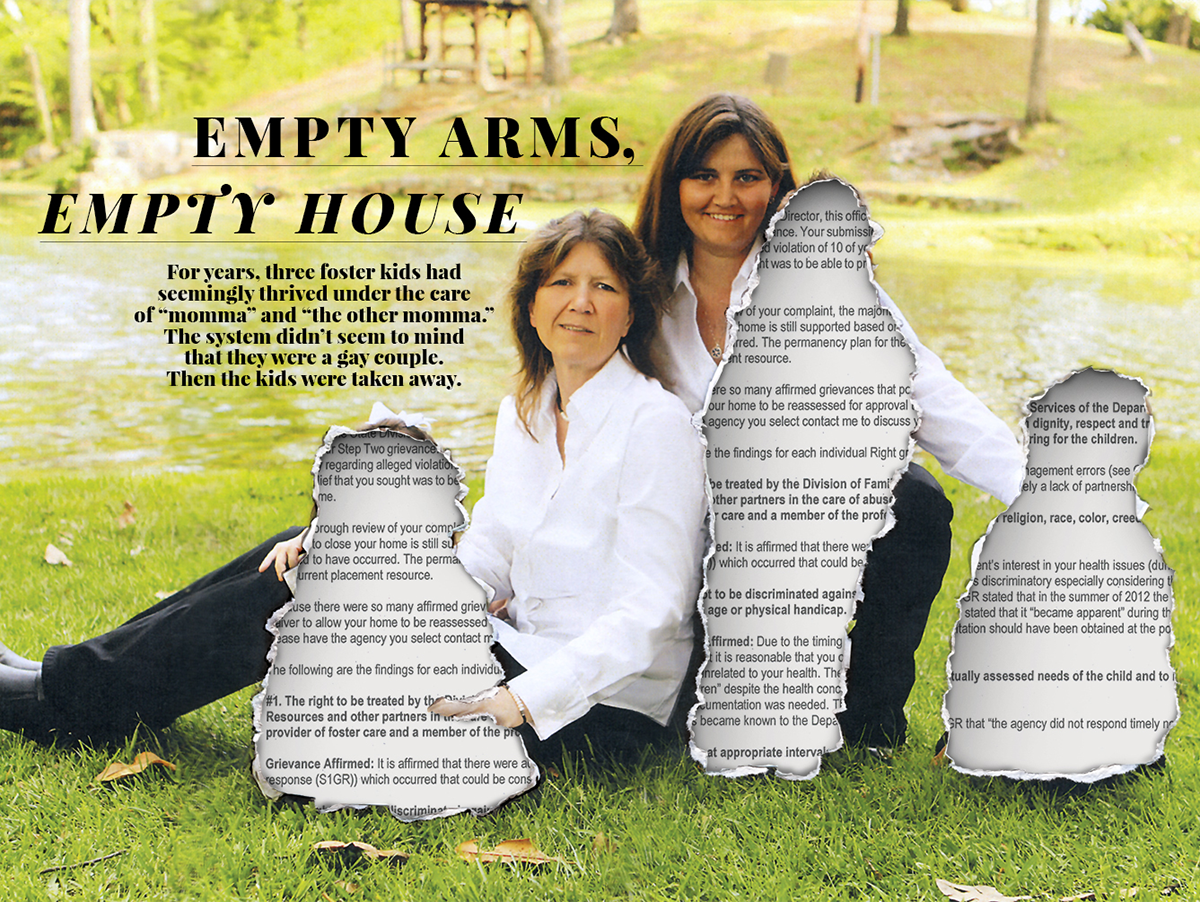

In the northernmost part of Georgia, Candice Dean and Jamie Chambliss knew that people would reflect on their Bibles when they saw them — two women in love — and scorn. But they assumed that churchgoers would turn a blind eye for the sake of the children.

Now the doors to the children’s rooms stay closed. Toys gather dust. Pictures are hidden away.

Officials in Atlanta told the couple they need to forget about what happened, that every legal option they had is at a dead end. The paperwork is final.

Still, the women can’t let go.

They keep a thick red binder to prove that something precious was wrongly taken from them. They fill it with letters from neighbors and family and co-workers, letters saying they are nice women, that the children were cared for. They fill it with explanations for every mosquito bite and bloody nose. They fill it with the frantic back and forths with caseworkers. They fill it so a lawyer can argue that what happened wasn’t fair.

And they wait.

Even though they have no rights in this part of the nation, they hope a judge will listen, that someone will care about what they lost.

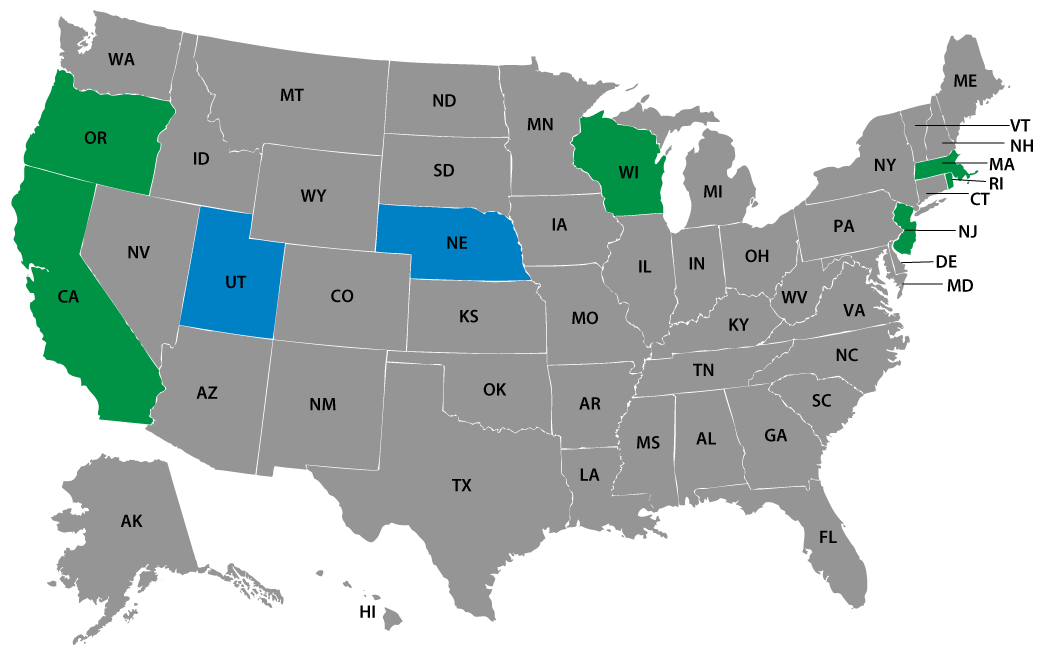

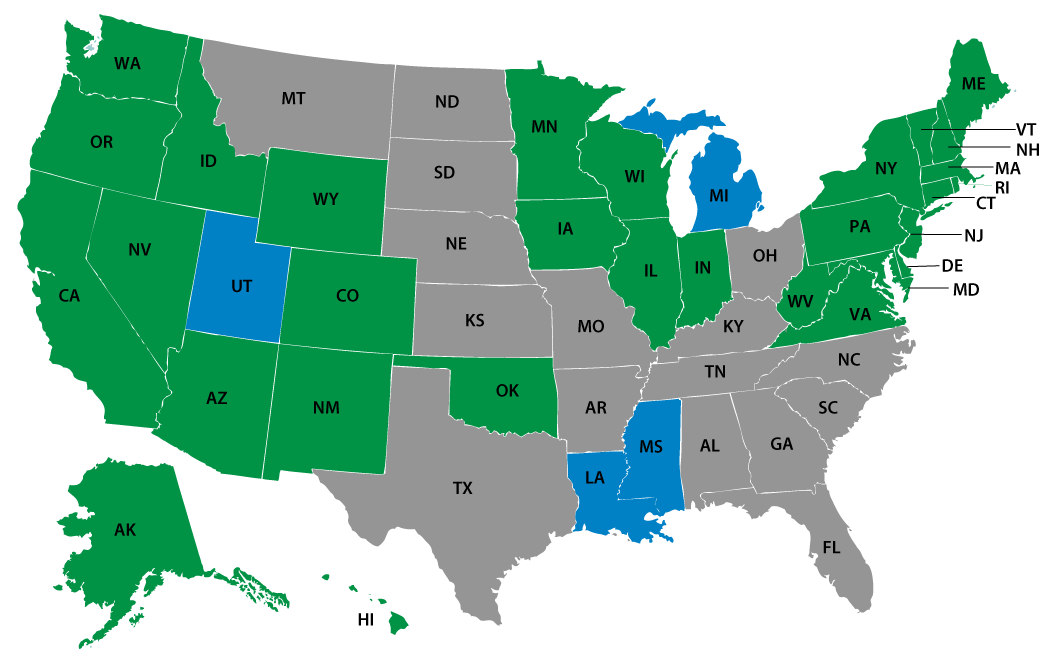

Thirty-two states now allow men to marry men and women to marry women. But while the legal definition of marriage is becoming more clearly defined, family law remains a gray area.

Many states, including Tennessee, Alabama and Georgia, are silent on whether gay individuals or couples are allowed to foster or adopt children. There are no policies or laws that say they can. There are no policies or laws that say they can’t.

So families built through the child welfare system are scattershot. Decisions vary from caseworker to caseworker, county to county, state to state, judge to judge.

Some state workers welcome same-sex couples, knowing there are more children in the system in need of placement than there are homes willing to take them. They cite research that shows children raised by same-sex couples are as well-adjusted as those raised by straight couples. Other caseworkers have strong religious objections and argue the children will be confused, face bullying or be prone to homosexuality.

And in places like Catoosa County, those morally opposed to gays adopting can wield a lot of influence, experts say. Even if state workers don’t verbalize their objections, they can easily act on them.

Anonymous accusations can delay proceedings. Missteps can be magnified. Interviews with the children can be twisted.

Without explicit protections, same-sex couples like Chambliss and Dean who partner with the child welfare system assume an enormous risk.

Adoption and foster care laws

Support for gay couples

Support for gay couples

No restrictions or support for gay couples

No restrictions or support for gay couples

Restrictions for gay couples

Restrictions for gay couples

The call came on April 1, 2011.

“Can you take six children?” a voice said on the other end of the line.

“We were only approved for one,” said Chambliss.

Ten minutes later the phone rang again. “Can you take three?”

After four years together, Chambliss and Dean decided they wanted a family. Chambliss’ two daughters from a previous relationship were gone. One had died in a car accident. The other was grown, in the military, with a life of her own. And Dean’s previous marriage had ended without children.

Initially they talked about Dean carrying their baby and finding a sperm donor, but the prospect seemed complicated. There were children already born who needed homes, they agreed. Chambliss had been one of those children. When she was 5 her mother abandoned her and her two brothers at a housing project in Illinois, and she spent the rest of her childhood skipping between foster parents and family members.

By applying to foster children, the two knew they would have to disclose their relationship, and they weren’t entirely comfortable with the idea. They weren’t ashamed of their choice to be together, but they also didn’t proclaim it. They considered themselves conservative, and had both struggled to reconcile their love for each other with their Christian faith. They had both been with men, but were happier together.

Still, the women believed their home could be a respite for children in the chaos of state intervention. Dean, who had been in the Air Force for nine years until she became disabled, worked for the court system in Hamilton County, and Chambliss, who was once a police officer, worked as a hospice nurse. They could provide stability, Chambliss believed. They would be part of the machine that made families whole again.

So when the call came, they were ready.

At 4:30 p.m. the same day, they arrived at the Catoosa County Division of Family and Children Services office to find three little ones. The baby was just 8 months old, the girl was 2 years old and the oldest boy was 3.

The infant was underweight and couldn’t lift his head. He smelled like urine, and his bottom was covered in sores from being left in soiled diapers. The young girl with tangled brown hair crouched barefoot in the corner of the room and wouldn’t speak. Her older brother spoke for her. He insisted on changing his own diaper and fired off questions, his words slurred by a speech impediment.

Chambliss and Dean were told little about how the children ended up in the custody of the state. Neglect and abuse were hinted at, but no specifics were shared. Chambliss said she was surprised the children didn’t cry for their real mother.

That night, when the couple sat them down to eat at the dinner table, the 2- and 3-year-olds crammed food in their mouths as if they hadn’t eaten in days. The older boy made himself sick by overeating. Then, in the middle of the night, Chambliss and Dean awoke and found food scattered across the kitchen floor, the refrigerator door ajar, the pantry flung open. In the children’s rooms they found food hidden away. The two older children slept on the floor, unaccustomed to having a mattress.

At first Chambliss and Dean assumed that their time with the children would be brief, a long weekend. But weeks went by, then months, and the children stopped acting like visitors. The women gave them nicknames, “Bubby” for the oldest boy and “Sissy” for the girl, and the brother and sister named the baby “Potato Head” because he loved mashed potatoes. But “Potato Head” gave way to “Tater Head” and “Tater Head” gave way to “Tater.”

The children gave their own names to Chambliss and Dean — Momma Kiki and Momma Mimi. Later it was just momma and the other momma.

A growing sense of comfort, of belonging, took root in the makeshift family. Neighbors said they watched the children blossom.

“These children are well fed, well dressed, well bathed, and well behaved,” Stephanie Fincher, who lived down the road, wrote in a letter the couple would later show to state officials. “I have never seen these children go without anything they need. Jamie and Candice show these children what a real family is, and how it feels to be loved and accepted.”

“The children have become an irreplaceable part of Candice and Jamie’s lives,” Rebecca Gephart later wrote in a letter.

“It is obvious that the children are raised in a very loving and structured environment. But most importantly I see that the children feel safe and have developed a very strong and trusting bond with both Candice and Jamie, which is a milestone accomplishment considering what they have been through,” wrote Sabrine Embry.

But, at times, there were challenges. Bubby was an anxious child and clung to Chambliss and Dean wherever they went. At night he picked his nose till it bled and bit his hands. Often he would hide around the house and ask Chambliss if he was going to get whipped. Unlike most foster parents, Chambliss and Dean decided to pay for him to see a therapist, and a counselor eventually diagnosed him with post-traumatic stress disorder. Of all the children, he remembered the most.

So Chambliss and Dean worked to build him up. They told him he was a big boy and that he could sit at the big-boy table at dinnertime and eat with big-boy utensils. They tried to make life fun. They signed him up for baseball and said he walked like he was 10 feet tall when he went onto the field, always making sure the mommies were watching. On weekends, they took him to Harley-Davidson rallies because he loved motorcycles.

And just as Bubby grew and changed, so did the baby. Chambliss and Dean watched Tater’s teeth come in. When he took his first steps, they hovered nervously. When he said his first words, they screamed with delight. When he finally used the potty, they clapped.

There were family vacations and birthday parties and hot afternoons at the park. They might not have looked like other families, but they acted like them. Around Thanksgiving one year, a teacher asked Bubby what he was thankful for and filmed his response. Dean kept a copy, the evidence they had done something right.

“I am thankful for my mommas, my sissy and my Tater Head,” he said.

At times Chambliss and Dean worried that their relationship would be an issue, but it never came up. They asked if it was a problem, but they were reassured by Catoosa County officials it was not. Just don’t tell the biological parents that you two are in a relationship, the foster parent supervisors told them.

So they didn’t.

Caseworkers appeared comfortable with the family. They came by for unannounced visits at 7 a.m. and 11 p.m. Chambliss would make a little extra for dinner because sometimes the workers stayed to eat. The women stayed in close contact with DFCS, sending pictures of every injury, communicating every trip out of town, every behavior out of the ordinary.

For two years, no issues with their parenting arose.

But behind the scenes the biological parents’ attorneys and some DFCS employees did talk about the women’s relationship and expressed concern, said two caseworkers who were very involved with the case but did not want to give their names because they feared retaliation.

When the parental rights of the children’s biological mother and father were terminated in 2013, Chambliss and Dean told the Division of Family and Children Services what they had known for a long time.

They wanted to adopt.

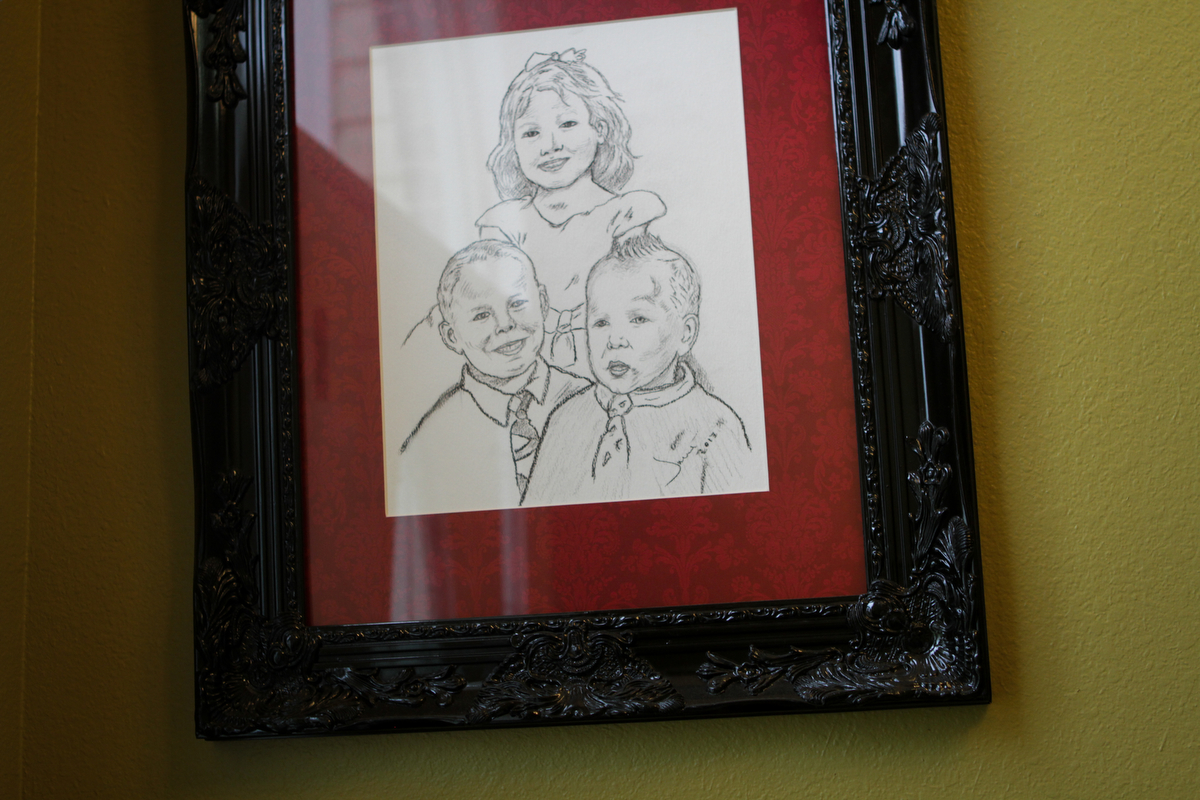

On the day they learned the children wouldn’t return to their real parents, the entire family dressed up for a family portrait. Sissy wore a white bow and a polka-dotted dress. The little boys wore ties.

When the camera flashed, they all smiled.

Around the time Chambliss and Dean announced their intention to adopt, Chambliss fell ill. A minor surgery resulted in a bile leak and internal bleeding, and it took months for her to recover. She couldn’t walk for a time, and a nurse’s aide had to come to the home.

In the meantime, the women asked the DFCS office to help them transport the children from time to time. There was a therapy appointment in Dalton, Ga., that they had trouble getting the kids to.

Teresa Ray, a caseworker, visited to talk about the transportation issue, and Ray told the couple that another caseworker tapped to help had been frustrated because she had to drive the children. She also told the couple they needed to be careful because this caseworker took issue with their “dynamic” and could put an end to their planned adoption.

Ray told them about a similar foster parent who had been fostering a child for 18 months and sought to keep the child permanently. The adoption fell apart when this caseworker got involved, and the child was moved and adopted by a traditional family.

“I don’t see that happening,” Chambliss said she told Ray.

Watch yourself, Chambliss said Ray responded. Find a therapist who can come to your home. Don’t make anyone drive the children.

Chambliss and Dean talked after Ray left and agreed they weren’t going to worry. The children had been with them so long. There had never been any issues. What could happen to derail the adoption?

Around a week later the caseworker Ray warned them about showed up at their front door.

Chambliss and Dean and the children had just returned from a vacation to Helen, Ga., and were still unpacking. Bags were everywhere.

“Where do you keep your guns?” Chambliss said the caseworker asked.

The handgun was in a locked gun box in a bedside table. They had taken the gun with them on their trip and had not yet placed it in their gun safe.

The caseworker asked to see their gun permits, and Chambliss and Dean produced their documentation. The caseworker told them the gun should have been in the safe, and they assured her the guns typically were.

Then, a couple of weeks later, in July 2013, Dean got a cryptic message on her phone.

The children had been taken from day care. They were being removed from the couple’s home. The state had received an anonymous tip that the women were physically punishing the children.

The women filed an appeal immediately and scrambled to gather evidence in their favor, anything to show that they would never and had never hit any of the children. And a month after the children were taken and placed with another foster family, Chambliss and Dean met with officials from DFCS about the charges.

Whoever reported corporal punishment had said Bubby said Chambliss slapped him when she came to see him at the day care, the DFCS officials told the women.

“Where is the video?” Chambliss asked, knowing that the day care was under video surveillance.

“Where is the proof? Are there any pictures of a slap mark?” she prodded.

She and Dean showed email after email where they had written DFCS caseworkers about Bubby’s penchant for lying. When he picked his nose and Dean would find him bleeding profusely he would often say that his sister had hit him or that the baby had hit him.

“I have reported incidents in the past where [Bubby] has made similar false statements using not only myself but others as well,” Chambliss had written Kim Stephens in July 2012.

Even if Bubby did say he had been slapped, which they doubted, that wouldn’t have been out of the ordinary, they said.

Then they brought up their conversation with Teresa Ray. They said they had been warned that a caseworker had a problem with their family dynamic, that they had been told that if this person got involved, that things would begin to come apart.

And the tone of the meeting changed. The charge was unsubstantiated, the officials at the meeting agreed. The children would return to the home.

But, going forward, Chambliss and Dean said they didn’t want that caseworker involved in their adoption, and the officials agreed. They would assign a Walker County caseworker.

“It is so obvious to me your level of commitment and love for these children and that you are their family,” wrote Jaime Stafford, DFCS Catoosa County director, days before the children were returned. “I appreciate so much … how you put the needs of the children first even though I know you both are very anxious and excited to see an end to this ordeal.”

Once home, the children seemed different.

If they left the house Bubby would get anxious and insist on knowing if he would be coming home to his room and his bed. He and Sissy started calling Chambliss and Dean by their first names.

“You can’t have two mommies,” Dean said Sissy told her one day.

“You can have two mommies,” Dean replied. “Sure you can have two mommies. I have two mommies and two daddies because I have a stepdad and a stepmom. Some people have two mommies. Some people have two daddies.”

Bubby said he was told he couldn’t call the baby Tater anymore. It’s OK, Dean assured him. He is still our Tater.

“You’re my momma, right?” Dean said the baby said one day, crawling into her lap. “You’re my momma. Only you.”

They asked why the children had started calling them by their first names. Who told them to do that? they asked the caseworker. But the women said the caseworker brushed it off. You know kids; they could have picked it up anywhere.

With time, things returned to normal.

Before Christmas in 2013 the couple spent months decorating the children’s rooms. They bought the boys matching twin beds with Harley-Davidson comforters, and a friend made them matching pillows. Chambliss stenciled motorcycles on the wall, and they found a clock in the shape of a wheel. In Sissy’s room they put down a pink carpet and covered the walls with peace signs and hearts. In the corner of the room, they placed a toy kitchen where she could play house.

On Christmas morning the doors to the rooms were wrapped with a bow and when the children looked inside the women said their reactions made them cry. They ran around, touching everything. The boys argued over who would get which bed.

“This is my room,” Chambliss said the children kept saying proudly. “This is my room.”

By the new year the adoption seemed all but guaranteed. But for the final steps of the process, officials with DFCS told Chambliss and Dean they needed to move their case back to Catoosa County.

Chambliss said she told them she still felt uncomfortable with Catoosa County overseeing the case, but she was assured the caseworker they were concerned about would only be in the background, handling the paperwork. So on a January afternoon in 2014 Chambliss and Dean agreed to return the case to Catoosa County.

Hours later, everything would change.

This time a Gordon County official called.

Another anonymous report was made with stranger accusations than the first.

Whoever called to report Chambliss and Dean said the couple withheld meat from the children, that the oldest boy was being starved, that they left the children alone at Walmart and that they fed a pepper to the girl and made her so sick that she was sent to the hospital.

The women were stunned. Those were all lies, they insisted. They could prove they were lies.

When the caseworker came to their house to investigate, Chambliss showed her the meat in the freezer, the chicken on the stove she was cooking for chicken and dumplings. She implored the woman to look at hospital records because the girl had never been to the hospital. This wasn’t the first time a false report had been made, Chambliss told the woman.

Is there someone who might have a reason to make unwarranted accusations? Chambliss said the investigator asked. Yes, they said. Before the investigator left, she told the women she believed the report was unfounded.

But two days later officials with Catoosa County DFCS called a meeting, an hour before the children were supposed to be picked up from day care.

Stafford, the Catoosa County director of DFCS, and Kate Trevors, the adoption case supervisor, sat in Chambliss and Dean’s living room and told the women that they would no longer be foster parents. The state was closing their home. The children would be removed permanently and there was nothing anyone could do about it.

Chambliss and Dean couldn’t believe it.

How could this happen? What did we do wrong? they asked. All the accusations were lies. The first report was shown to be wrong. This report will prove to be wrong. They were innocent, she said.

It’s the policy violation, Stafford said, the gun that wasn’t placed in the safe.

But that was six months ago, Chambliss said. The couple had completed a corrective action plan and gone through training for the misplaced firearm. Why is that coming up now, right before the adoption? If it was such a serious misstep why were the children allowed to stay with us?

It’s a state decision, Stafford insisted. It’s final.

Dean screamed and ran to the bedroom.

“They can’t take them!” she yelled. “They can’t take them!”

Chambliss ran after her.

“We’ll fight this,” Chambliss told Dean behind closed doors. “If I have to spend every dollar I have, we will fight this.”

Stafford told them they could keep the children for the weekend so they could say their goodbyes.

That night the couple tried to imagine what they would say.

We are not your mommas. We can never see you again. This is not your home. You will get a new home. You will be OK.

But they never said goodbye. They refused to accept the situation.

Chambliss worked frantically until the last hour calling neighbors and friends, begging lawyers to find a way to stop the state from taking the children.

Bubby’s birthday was the next week. So they rushed an early party, cobbled together mismatched napkins and plates and shared a Spiderman cake with his friends. They didn’t let the children see them cry. They didn’t let the children know how afraid they were.

Chambliss believed they would find a remedy at the last minute. When they dropped the children off at day care that Monday she thought the worst wouldn’t come to pass. They would bring them home again, she told herself.

But nothing could keep the family whole. Lawyers told her they couldn’t stop the machine in motion. These children were wards of the state, and the state determined their future.

By Monday night the children were gone.

Chambliss and Dean filed a grievance with the state. They talked with foster parent advocates and asked day-care workers and former caseworkers and the children’s therapists if they would testify for them in court. They asked a judge to intervene, but he denied their motion.

Then when their appeal made it to the state level in February, they traveled to Atlanta.

“What is your goal?” Chambliss said a mediator in the room asked them.

“We want our children returned to us. We want to adopt these children,” she responded.

A state official broke in. That was not going to happen, he said. The children will be adopted by another foster family.

Why? the women asked. What went wrong? What proof was there that they hadn’t loved the children, that they hadn’t cared for them and protected them? Why were they good enough to foster these children for years but not good enough to adopt them?

The man representing the state would answer only in vague terms. The children were starting to talk, he said. The children had said guns were often left out.

“Well, did you ask them what colors our guns are? Did you ask them to describe the guns?” Dean asked the man. “My gun is purple. They would know that if they had seen it. But I know the children never saw it.”

The state would believe what the children were saying. End of story, he said.

Not long afterward, in March, the couple got a letter in the mail.

A majority of their grievances were confirmed, it said. Their rights to be treated with “dignity, respect and trust” were violated, the document stated. In fact, there were so many case management errors that the state would consider continuing to allow the couple to foster children.

But because of two policy violations — the corporal punishment charge that had been unsubstantiated months before and the misplaced gun finding that had been addressed with a corrective action plan — they would not be allowed to adopt the children.

“The permanency plan for the three children in question will continue to be adoption with their current placement resource,” the letter said.

Although the charge of corporal punishment was unsubstantiated — meaning it did not rise to the level of an ongoing concern of maltreatment — it was still considered a violation, Susan Boatwright, a DFCS spokesperson, would later explain when the Times Free Press inquired about the case. An unsubstantiated ruling didn’t mean corporal punishment wasn’t used.

Still, officials wouldn’t say what proof they had that corporal punishment had occurred. They also couldn’t explain why so many issues arose after the couple declared their interest in adopting or why the state waited to act on the violation until months later, right before the adoption was finalized.

“It was just a coincidence,” Boatwright said.

In the end, the state believed the children weren’t safe with Chambliss and Dean. The decision was about safety, not the couple’s relationship, she said.

Months passed.

Behind closed doors, Chambliss and Dean’s case became a divisive issue among Catoosa County caseworkers. Even Boatwright acknowledge “this case was very emotional at the local level.”

In March, Stafford, who defended Chambliss and Dean, was asked to voluntarily step down as Catoosa County director, according to personnel records. One worker who was close to the case but wouldn’t give her name changed jobs because she was so disillusioned by the outcome. Another caseworker, who also wouldn’t give her name, said she quit because she was disgusted with the way the two women were treated.

“I have lost sleep over it,” said the former employee, who has been to court dozens of times in the case. “I ignored my own family over this case. … I left [work] crying many times over this whole deal. I know there were these little children with their hearts broken. … The children were done an injustice by the system.”

Chambliss and Dean left the children’s rooms as they were, but they closed the doors. They took down all but a few of the family pictures hung around the house. A sketch of the three children that Chambliss drew still hung near the front door. They continued recording the children’s favorite shows on television. Three nights a week, they watched a friend’s baby so the house wasn’t so quiet.

Depression plagued them. Chambliss took medications to lift her mood, unable to move beyond the humiliation she felt. She was the type of woman who prided herself on getting A’s on college papers and never having a speeding ticket. Now she had been told she wasn’t fit to mother.

And they both were angry. They were glorified baby sitters, they said. They took in three children who were malnourished and underdeveloped and grew them into children people wanted to adopt. Then they were railroaded by the system and not allowed to defend themselves.

“We were the ones. We got all of them talking. We potty-trained them. Now they are adoptable. Now they are kids that people want, and our job is done,” Dean would tell Chambliss.

Yet the most infuriating thing was the way the state treated the children, the couple said, yanking them back and forth, confusing them. They didn’t even pick up Tater’s stuffed monkey, the one he slept with every night, Chambliss said.

This summer Chambliss and Dean hired a new attorney who filed a motion to intervene with the juvenile court in Catoosa County. In it, they explicitly state they believe they were denied adoption because of their sexual orientation and call the actions of the state “malicious,” even though they know there is no law protecting them from that type of discrimination.

Their attorney, Robin Flores, told them it would be an uphill battle without precedent.

But this time the judge agreed to hear the case.

When the private hearing is held in December, they hope this year of separation will be over. The judge has great latitude and could intervene and order the children returned. He also could do nothing.

Until their lawyer tells them there is absolutely nothing they can do, they will keep pushing. They will drain every dollar of their savings if that’s what it takes, they say.

They want the children to know they wanted them, they always wanted them.

“What parent wouldn’t fight to the end of the world?” Dean told Chambliss on a recent afternoon. “We have that instinct.”

This story was reported over five months. The narrative is based on extensive interviews with Candice Dean and Jamie Chambliss; interviews with current and former caseworkers; 21 letters from co-workers, friends, neighbors and family; 176 pages of email records between the couple and officials with the Catoosa County Division of Family and Children Services; personnel files and official Child Protective Services investigation findings. Additional interviews with national adoption researchers and attorneys who specialize in adoption and discrimination law informed the reporting. The names of the three children in the story are left out to protect their privacy.

Story by Joan Garrett McClane

Photography by Maura Friedman

Art Direction by Matt McClane

Design and production by

Maura Friedman, Mary Helen Miller & Ken Barrett