They came from across the city.

They came black and white

to the towering brick house

on Read Street.

Bankers, lawyers, judges, government workers, retirees, contractors, small-business owners — a constellation of the middle class.

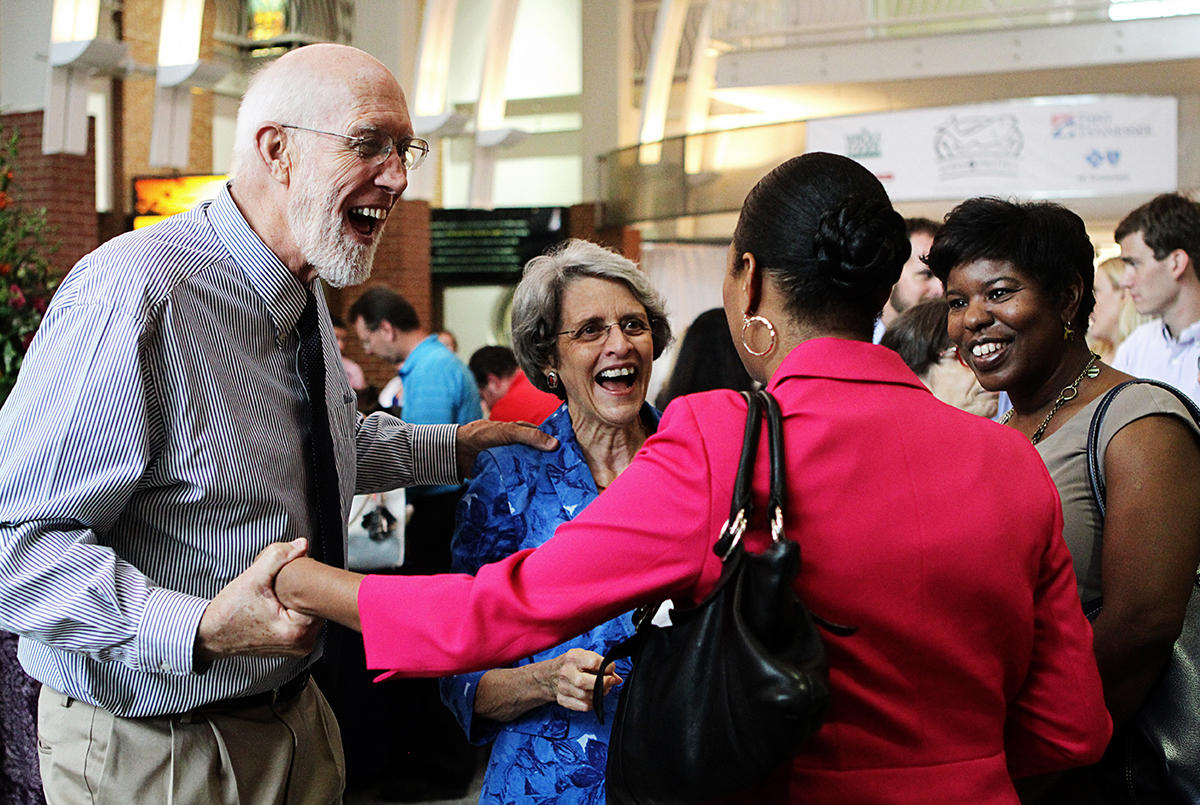

Greeted with tiny coffee cups and wedges of chocolate cake, they stuck name tags to their shirts and blouses and exchanged polite hellos and handshakes until a bell rang and the crowd settled like dust into chairs and couches. Forty-five people, many meeting for the first time, crammed into the living room and waited for a word from the host.

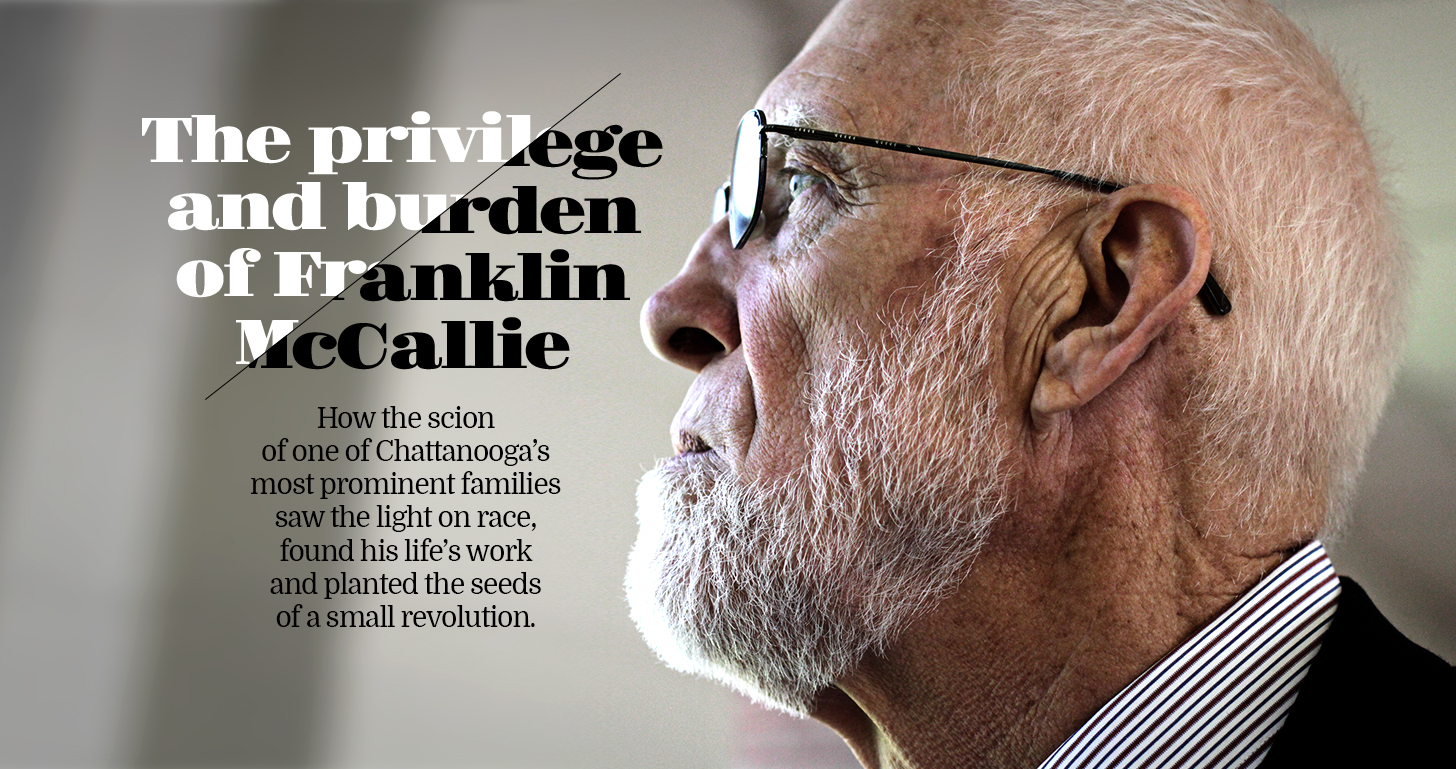

Franklin McCallie looked across the room and was in awe of the sight. The mix was just right, he thought.

This would be the perfect beginning to his small revolution.

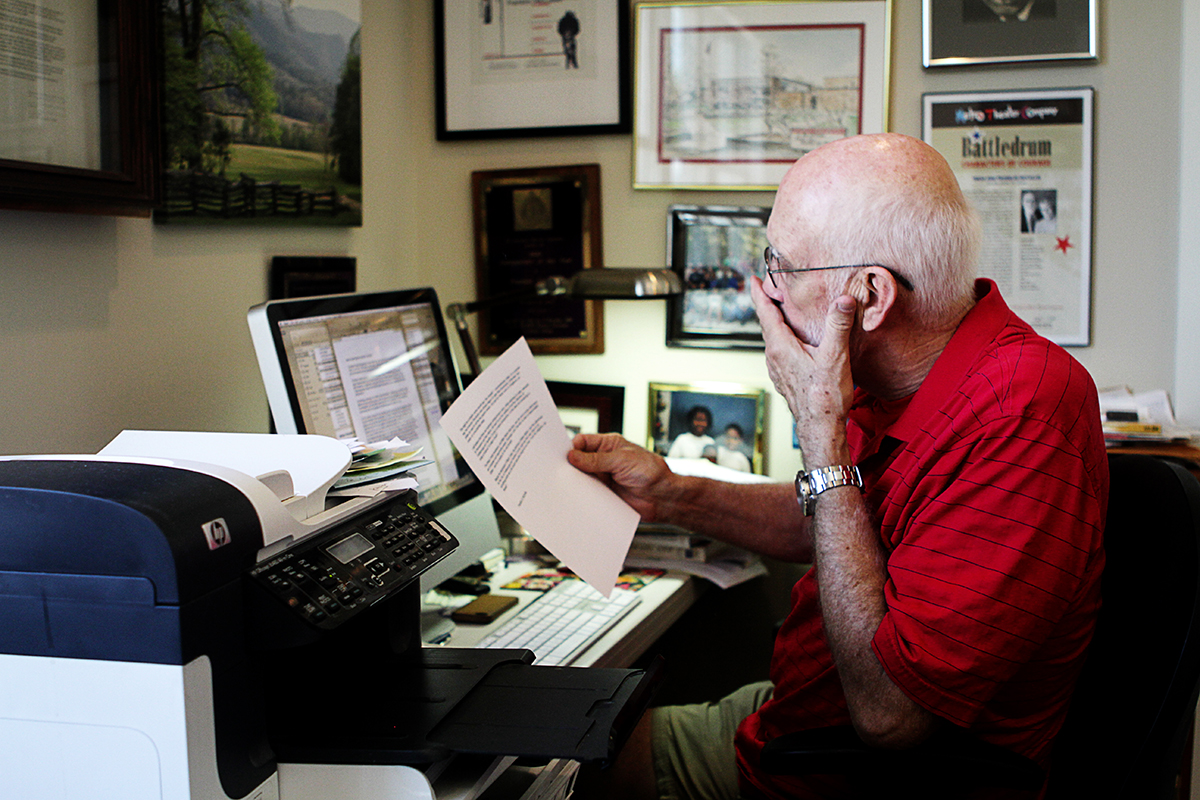

A 74-year-old pillar of a man, Franklin stood at the head of the room. He came from old Chattanooga, good stock. His name alone had drawn many people here this night. Streets and scholarships bear his name. Everyone waited with nervous energy for him to say something profound.

“Friendship,” he said, pausing. “We are here to to talk about friendship, black and white.”

It seems so simple, he said. Isn’t it a conversation for children? Isn’t it?

But we have never really thought about this, have we? So stop. Think about it, he said. We don’t eat at the same tables or worship in the same chapels or live on the same blocks. We don’t choose one another. We don’t trust one another.

And what is it doing to us?

He scanned the crowd. There was silence. A few wiggled in their seats, their consciences pricked.

“How many of the whites in this room have a close black friend, a real black friend?” he asked.

Only a few hands went up.

Well, that is going to change, he said, starting tonight.

It started with a conversation among family and an email, a half-hatched romantic idea. Just dessert. Just conversation.

But within a year Franklin McCallie’s house on the Southside became center stage to a novel social experiment. Fifty or so guests were invited at a time, the mix always intentionally a third black and two-thirds white. The whites, he strongly believed, needed the exposure. And the goal was simple: Come as strangers and leave as friends.

Over time the strange gatherings multiplied, spilled into other homes. Word spread, sparking curiosity and skepticism. Its own organizers wondered about its effect on the whole. But Franklin believed they were remaking the psychology of those who attended, person to person they were dulling the effects of a segregated society that continues to survive unquestioned.

The nights evolved through trial and error. At one gathering, blacks and whites rubbed noses. A white woman said she was glad the blacks had dressed appropriately because she wouldn’t have talked to them if they had worn their pants low. Blacks said blacks are racist, too. They laugh at blacks that act too white. Blacks said they were tired of getting looks when they shop, having store clerks assume they are either poor or criminals. Whites admitted they are too reticent to talk to blacks, afraid they will say something wrong or offensive. Blacks said they call some whites their friends but don’t invite them to their homes.

There were tears and laughter and honesty. “I needed this,” said a man who had argued with Franklin about race for 50 years. True friendships formed. Removed from the framework of politics and policies, small miracles took place.

And to Franklin, it was work that must be done. He put energy to it, as if he were saving souls. Every white lawyer living sequestered on Signal Mountain and every black woman keeping to her kind in Alton Park was in danger of a life littered with misunderstanding, he believed.

While others say the world has changed, Franklin remains a vestige of the great civil rights struggle, of a time when little black girls lay dead from bombs and white-hooded white men strung up the innocent because they couldn’t see past the color of their skin. And Franklin is still fixated on the inequalities that remain, both the intentional and the unintentional.

Slavery is dead.

Jim Crow is dead.

Plessy v. Ferguson is dead.

But Franklin says their ghosts are everywhere.

He sees them at grocery stores, in the face of a black woman who won’t look him in the eye. He sees them on the free city shuttle, where white tourists scoot away from black riders. He sees them in his white friends who can’t think of a time when they shared a meal with someone of a different race, and who don’t know why. He sees them in the poverty of the projects. He sees them in the headlines from Ferguson, Mo., in the photos of the police in riot gear and black teenagers in protest.

We no longer have the stomach for forced separation. We are careful about our words, about appearances. We call ourselves post-racial, diverse, multicultural, a melting pot, a part of the South that learned its lesson. But in many ways we remain apart. You can live a lifetime in Chattanooga, as you can in many other cities across America, and never truly know a person who looks different.

Race in Hamilton County, today and 1950

Take a closer look at the points where we intersect. Look at the clusters of teenagers at the mall. Watch the children in the lunchroom. Pay attention to who huddles near the coffee maker during breaks at the office.

And Franklin can’t stand it. He can’t look away.

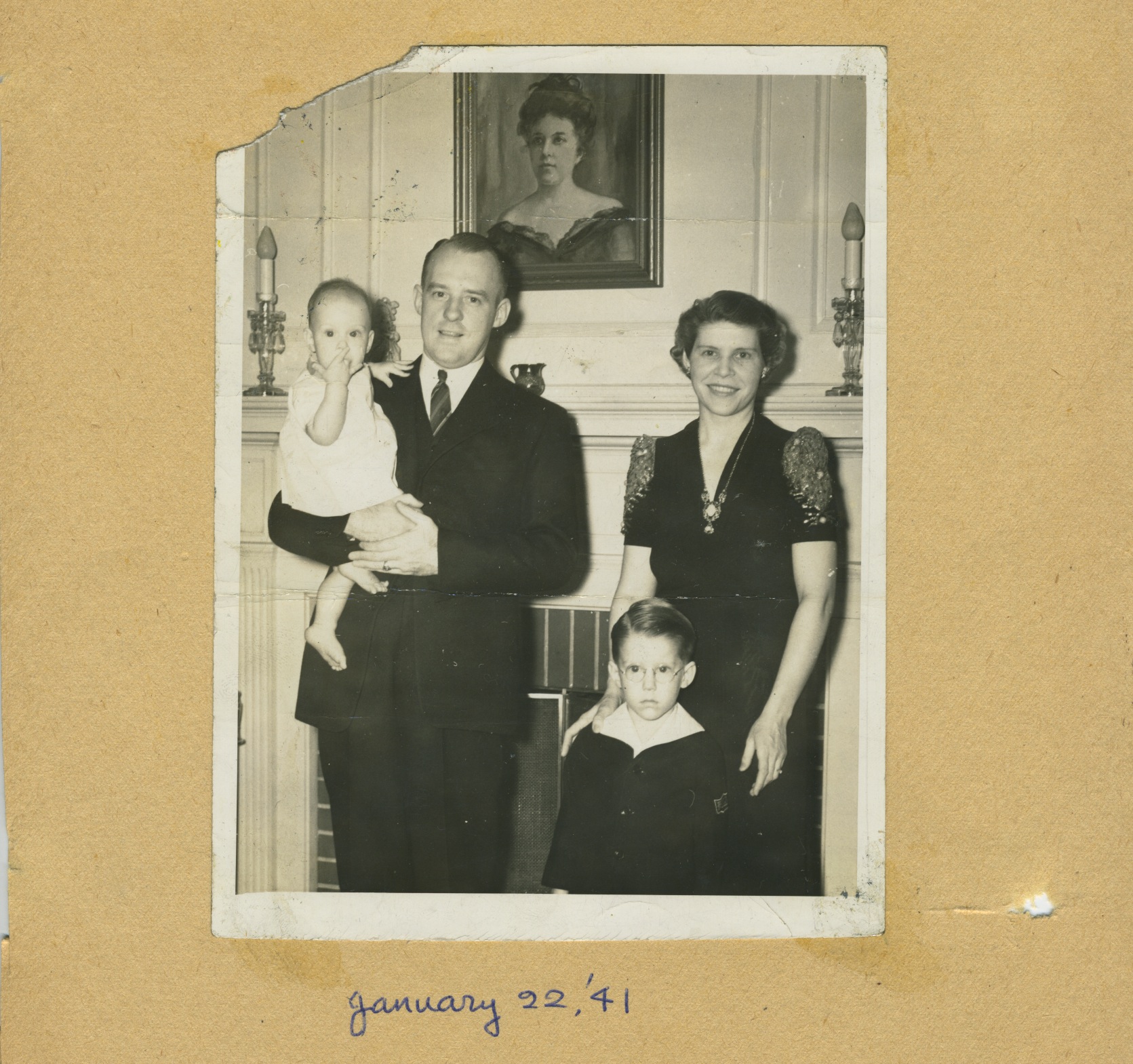

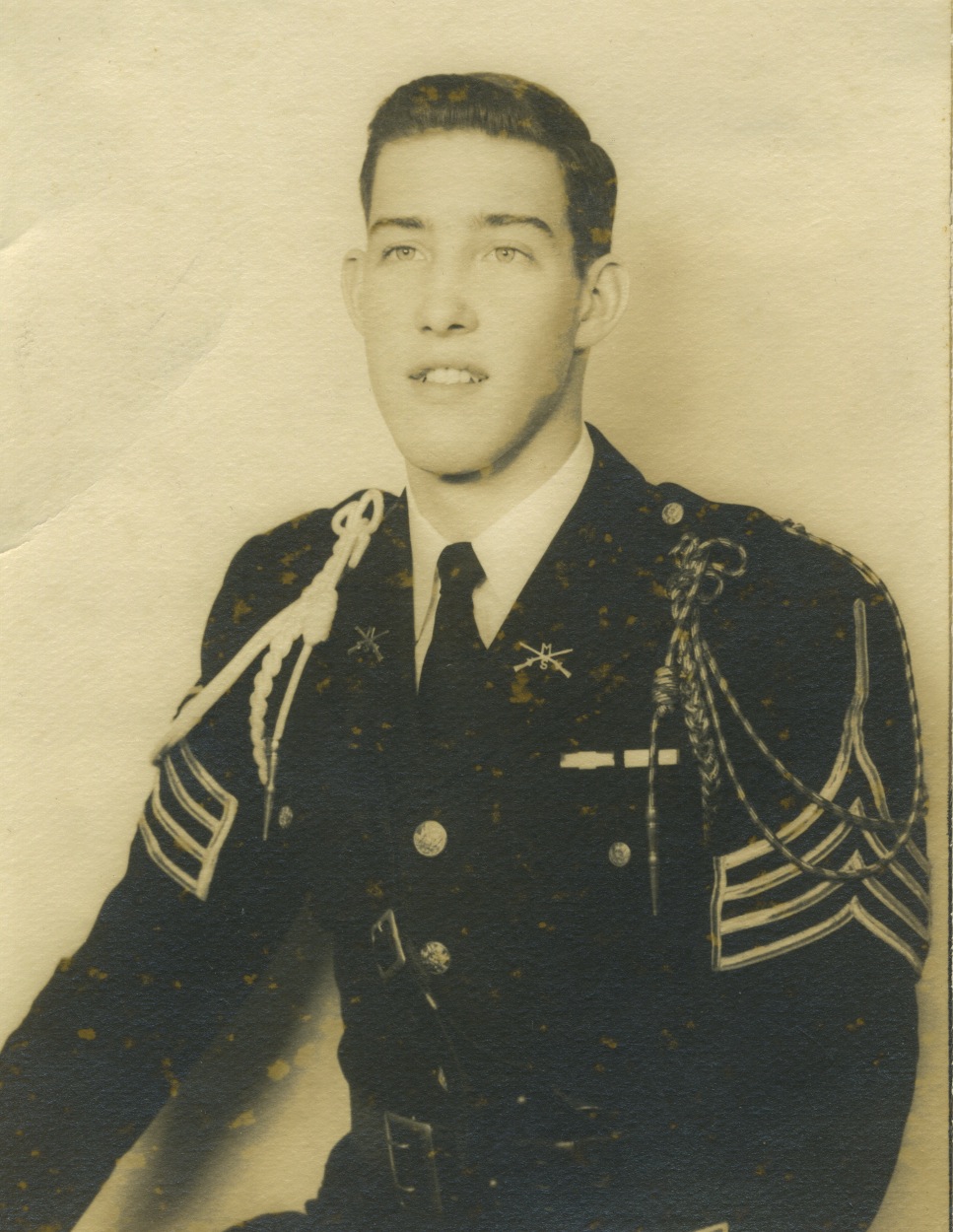

Franklin was born into privilege, a favored son to one of the great, white Chattanooga families, and he grew into a man on the grounds of one of the South’s most prestigious schools for boys, The McCallie School, the school his family founded.

"Ms. Lucille,"" a black woman, raised him and bathed him and paddled him, but Ms. Lucille was not allowed to eat at the table with his family. Ms. Lucille ate alone. At school, black men served his lunch and washed his clothes, but their sons were not allowed to attend the school. Franklin took no notice. When he sat down in a bus beside a black traveler, Franklin expected him to move into the crowded back.

Like his father, Spencer Jarnagin McCallie Jr., and his father’s father, Spencer Jarnagin McCallie Sr., Franklin believed in segregation. He believed blacks were meant for lesser things. Noah cursed Ham with black skin in Genesis and destined his descendents to servitude, his pastor taught. The chasm in fate existed as a profound moral lesson.

“Jesus loves the little children of the world,” he sang at church. But not the black children in America.

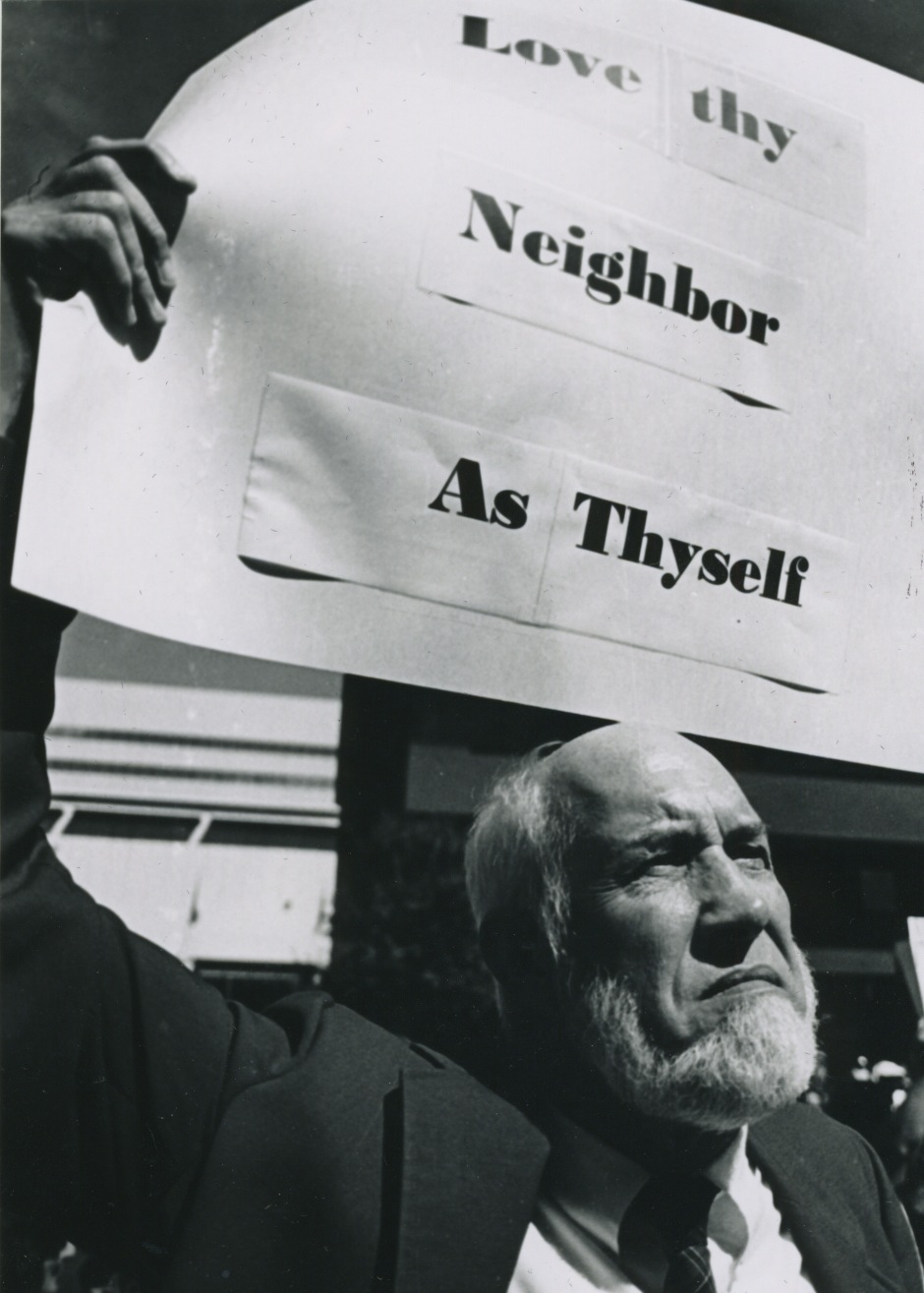

“Love thy neighbor as thyself,” he read in the Bible. But not your black neighbor.

His father passed down the decades-old Southern resentment that remained more than a century after the end of the Civil War. As a boy, Franklin said, he remembers how thinking about Civil War battle scenes would move his father to tears.

The order of the world seemed clear. There were opposing forces. The South and the North. The whites and the blacks. The Christian and the non-believer. And young Franklin was taught that he was the best of them all, a Dixie baby with pale skin, washed in the blood of Jesus.

When his father told him that U.S. Supreme Court justices were ruining the South with their forced integration, Franklin believed him. When his mother warned Franklin not to listen to the sympathizers who used words like "equal" and "fairness,"" he promised he wouldn’t.

Franklin wouldn’t meet a black person his own age until he was a junior at all-white Rhodes College, then called Southwestern at Memphis, more than 300 miles away from his family.

At a Sunday night Presbyterian fellowship, one of his fraternity brothers announced that he was helping organize a dialog between Rhodes students and students at the black college on the other side of Memphis, LeMoyen-Owen College. Franklin had refused to attend at first, but his friend persisted. He told Franklin he needed to be there, “to learn what the colored kids think.” It was 1961, the year of the Freedom Riders and sit-ins, and race was the politics of the day.

Two weeks later, Franklin found himself in a small room with three black students talking about college and classes, at times just staring at one another.

They were well-dressed, polished and smart, not what he had expected, not what his father had told him to expect. And they were funny. He was taken off guard by their jokes, even found himself laughing.

On some level, his admiration turned to anger.

“Tell me why the colored troops in World War II were lousy soldiers?” he said, unprompted to the black man leading the conversation.

“Did you have a family member fight in World War II?” the black student asked, brushing aside Franklin’s insult.

“I had two uncles,” Franklin said.

“So did I,” the black student responded. “I had two uncles that fought.”

“So were my uncles,” the black student said.

“What do you think they were fighting for?” Franklin said. “Freedom.”

“So were my uncles,” the black student said.

“Let me ask you something,” he said, continuing his interrogation. “Do you ever shop in downtown Memphis? Do you ever eat in downtown Memphis?”

Franklin became frustrated, wondering where the questions were leading.

“Yes,” he said.

You know where my uncles and I eat when we shop in downtown Memphis?”

“No,” Franklin said.

“My uncles, the ones that fought for freedom, and I, we get on a bus and ride two miles out of town to eat in colored town because no one will let them eat in their stores.”

It’s a story Franklin has probably told a thousand times over the past 50 years, always stopping to cry at the end. It was the day of his salvation.

It was the day of his salvation.

The black student just stated the obvious. But, in that moment, imagining the black man’s uncles as soldiers, soldiers like his own uncles, Franklin saw everything anew. He remembers feeling ashamed of his racism for the first time.

A single conversation — a chance meeting — would radically alter his plans and his future.

When he got to his dorm room that night he said he laid on his bed and cried for three hours. A few days later, he dropped out of college.

When Franklin came home to Chattanooga he didn’t argue with anyone about race, not yet.

He tried to explain to his parents about what happened in Memphis, about the black student and his uncles, but people told him he didn’t make sense. An uncle sat him down and told him he was an embarrassment to the family name.

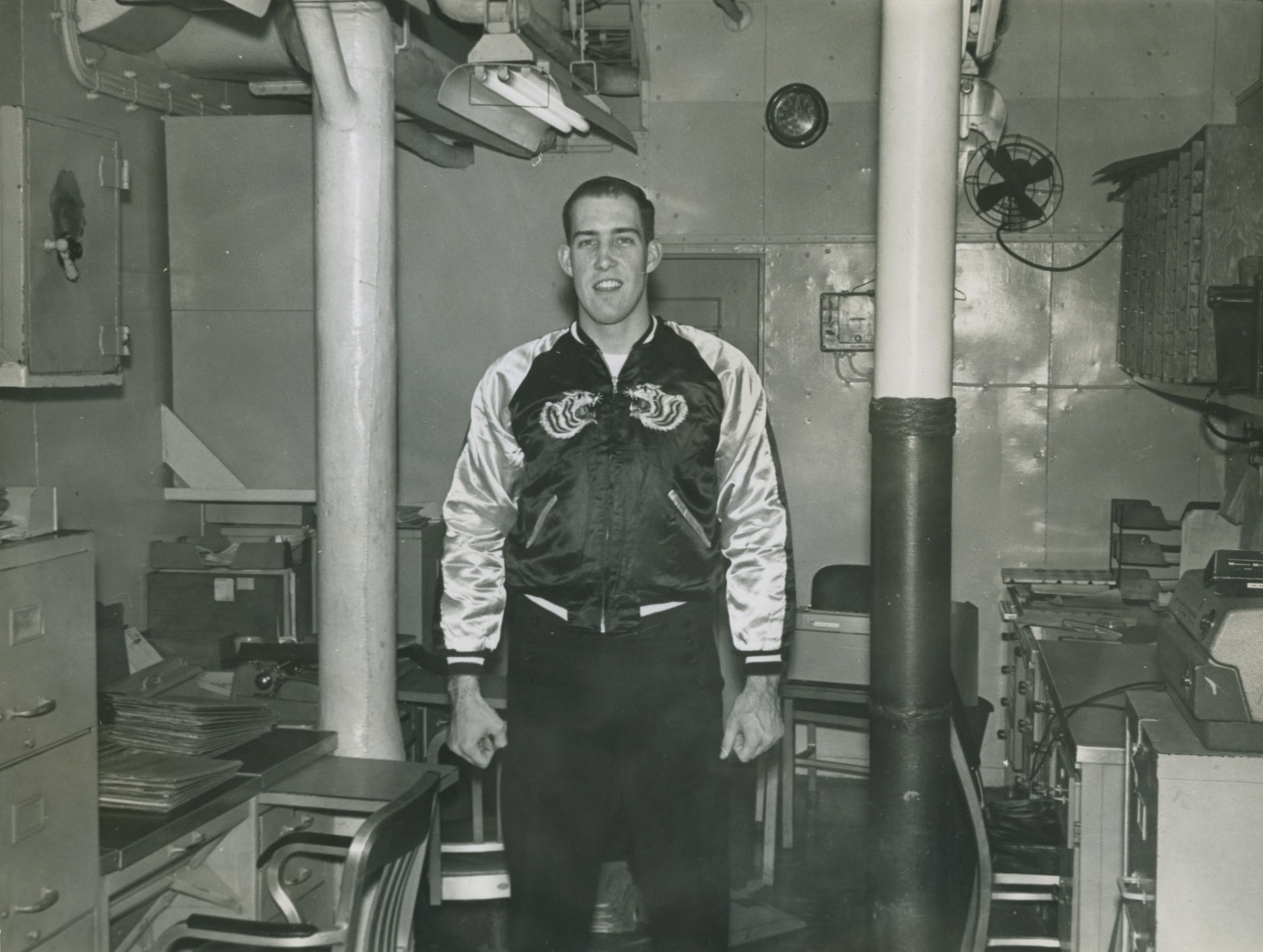

For a short time, Franklin worked as an orderly at Erlanger hospital before joining the Navy for two years. Then he married his high school sweetheart, Tresa Brandfast, and moved to Baltimore, Md., to finish his degree in education. After graduation, he taught for two years in Maryland and then completed a master’s degree program at Harvard University.

In 1968, he decided to come back to Chattanooga, emboldened. He told his father he would teach at McCallie School, but only if it integrated. His siblings and cousins also pressed the longtime headmaster.

It was an argument that lasted all summer, and two weeks before school started the tension escalated. Blacks and whites can live together, Franklin told his father. Blacks are as smart as we are. The Bible teaches us to love.

Hover over dots to see racial breakdown of Hamilton County Schools.

Source: Tennessee Department of Education. 2012-2013 Report Card.

Graphic by Mary Helen Miller

“Dad, you taught us the philosophy; we are just implementing it,” Franklin yelled.

His father slammed his fist on a wooden table.

“Don’t ever come back into this house and talk about race with your father,” his mother scolded.

So Franklin gave up on convincing his parents.

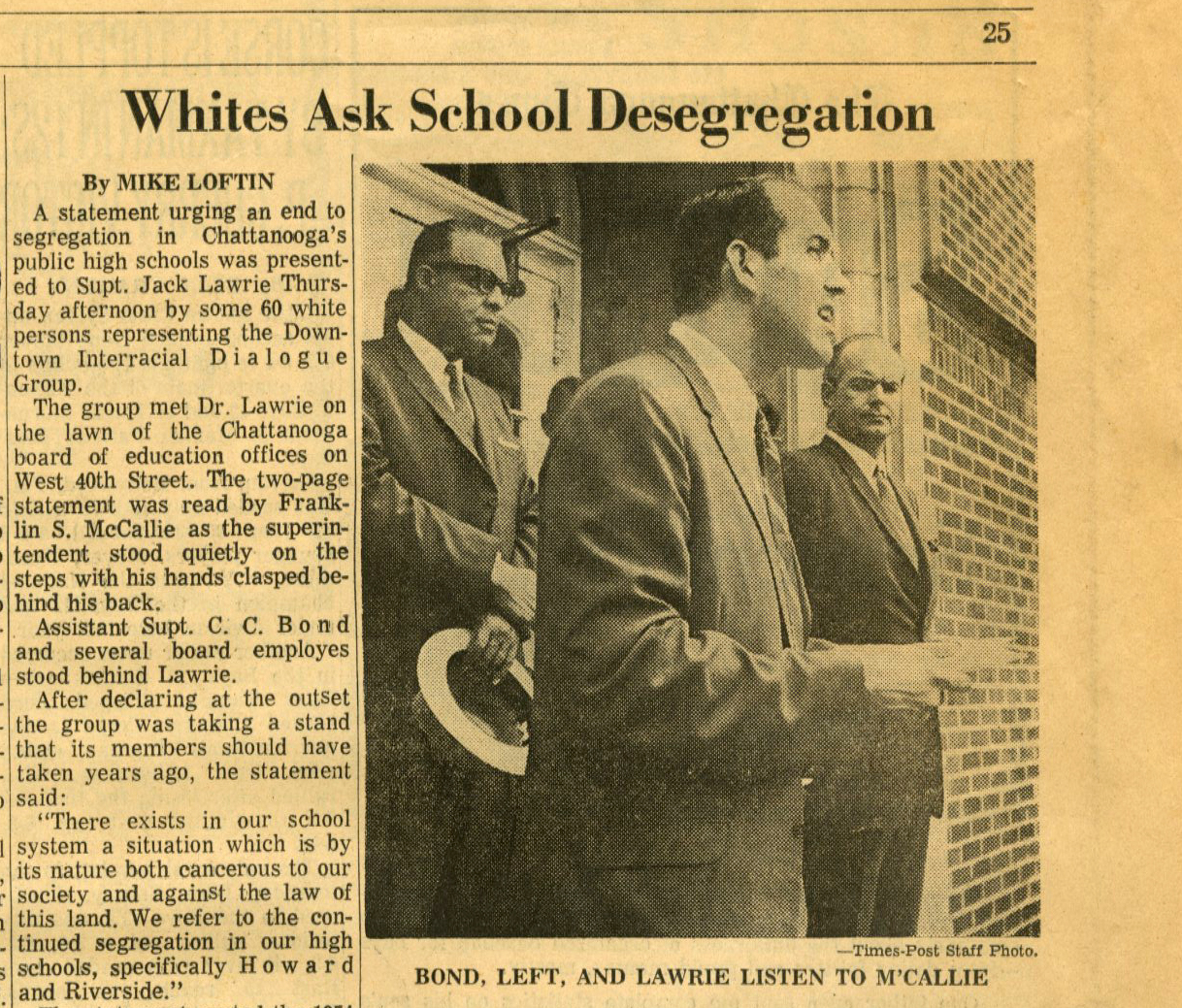

He applied to teach English at Howard School, an all-black school, and he became even more consumed with the civil rights movement. He spoke at churches, protested for equality and lobbied politicians. He would be one of the few whites to stand with blacks at the time and become the first white administrator at Howard. His father would see his face in the newspaper marching in protests and call him to say he was throwing his reputation away.

At times, the views of people like his father seemed unmovable. Perhaps a shift would come only with the death of a generation, many in the civil rights movement said. But Franklin had seen segregationists soften, and he held out hope for his father.

Finally, the day came.

Franklin had driven to a downtown bank to thank an influential Kiwanis Club member for inducting its first black member, but when he offered his congratulations the man acted confused.

“What for?” the man replied.

“You got those 100 white men to…”

“Franklin,” he said. “Didn’t you know? That was your father.”

When he found his father on the McCallie School campus later that day the two embraced. Franklin cried on his shoulder. When he looked at his father’s face he saw embarrassment.

“I’ve been wrong about black people my whole life,” he told Franklin.

He would integrate McCallie, he told Franklin, and with his leading the rest of the city’s elite private schools would follow suit in the early 1970s.

A few years later, Franklin left the South to finish his education. With his wife and two young children he lived in Chicago for a time and eventually settled in the St. Louis area where he worked as an administrator at two high schools. There he made headlines, too.

As assistant principal he chased down and tackled a gunman on his campus who had shot three students. Franklin kept him pinned until police arrived.

As principal in another school, Franklin quadrupled the number of students in advanced-placement courses, and improved the school so much that property values increased in the community. He helped develop one of the best high school journalism programs in the country and defended student journalists’ independence, even when they chose to run an advertisement for Planned Parenthood. He forbade use of the word “fag” and ruffled feathers when he defended gay students at a time when they were widely ostracized. And he could often be found in the black community, shaking hands and speaking at churches, telling parents about the value of every child.

When he left after 22 years, the school held ceremonies for days. People waited in line for hours just to say goodbye. He always knew everyone’s name, a student said. He was a moral leader, the teachers said. Locals tried to convince him to run for mayor of the city of Kirkwood, but he refused.

Then, after three decades away he decided to come home. He told a local newspaper he wanted to return to his roots.

In 2011, at 71 and retired, Franklin and Tresa bought a house in one of the city’s few integrated neighborhoods, Fort Negley, named for an old Union general, and they decided to hire a black contractor to reconstruct the home. Blacks didn’t get the same opportunities as whites in business, and he wasn’t going to be a part of that, he told his wife.

At 68, Bobby Joe Adamson got the job.

Bobby Joe wasn’t used to trusting whites. He was the son of a sharecropper and grew up listening to his father’s stories about working and not being paid, about running through the woods, bullets flying over his head. Bobby Joe had felt the sting of racism, too. He had lost jobs because he was black. At the brick mason’s union hall he drank out of the black water fountain. When he became a contractor, banks turned him down for loans despite his good credit. His father had always told him to be careful with the whites, and he listened.

Then he met Franklin.

As Bobby Joe worked on the house, he and Franklin talked about banisters and wood and crown molding, but they also swapped stories about the past. Franklin confessed to Bobby Joe that he was once a racist, that he had grown up ignorant and privileged and that he hadn’t outlived the guilt.

He recited to Bobby Joe the stories about the student in Memphis and his revelation, and his father. He would cry in the retelling, and Tresa would whisper that he gets very emotional in the remembering. At times, Bobby Joe said he wanted to tear up himself, listening to a white man apologize for his sins. He never believed he would see it in his lifetime.

If genuine, Franklin was an anomaly, Bobby Joe thought, even a little obsessed.

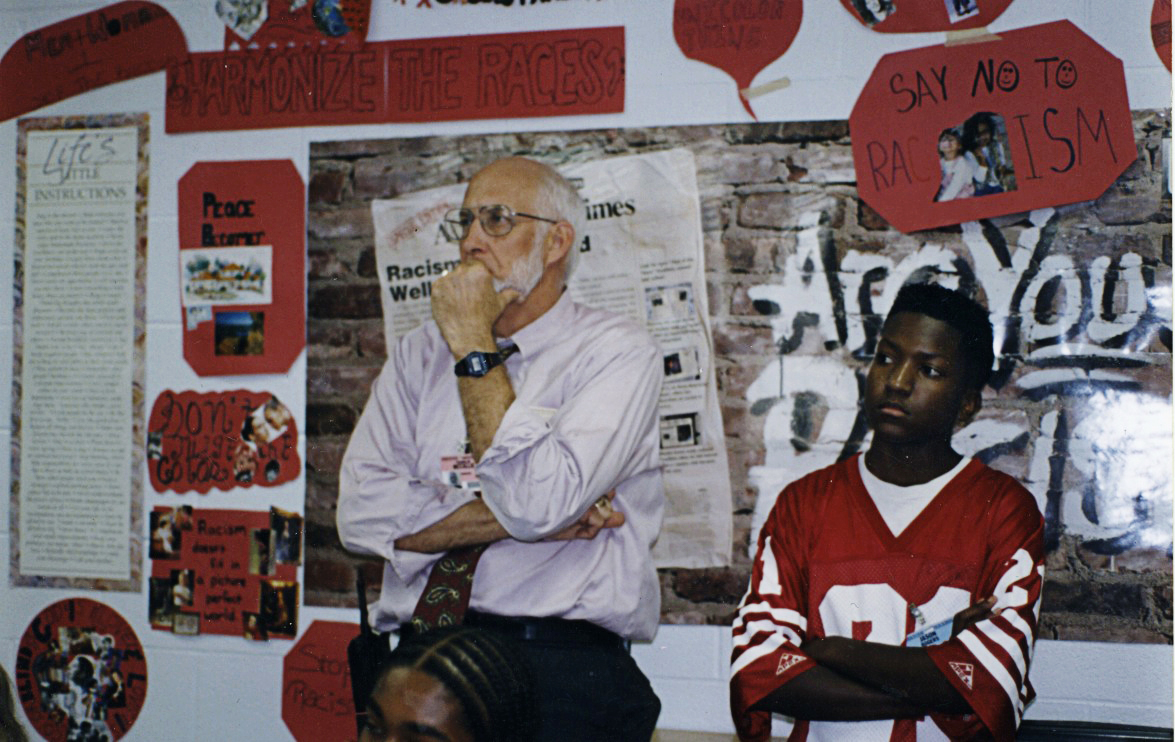

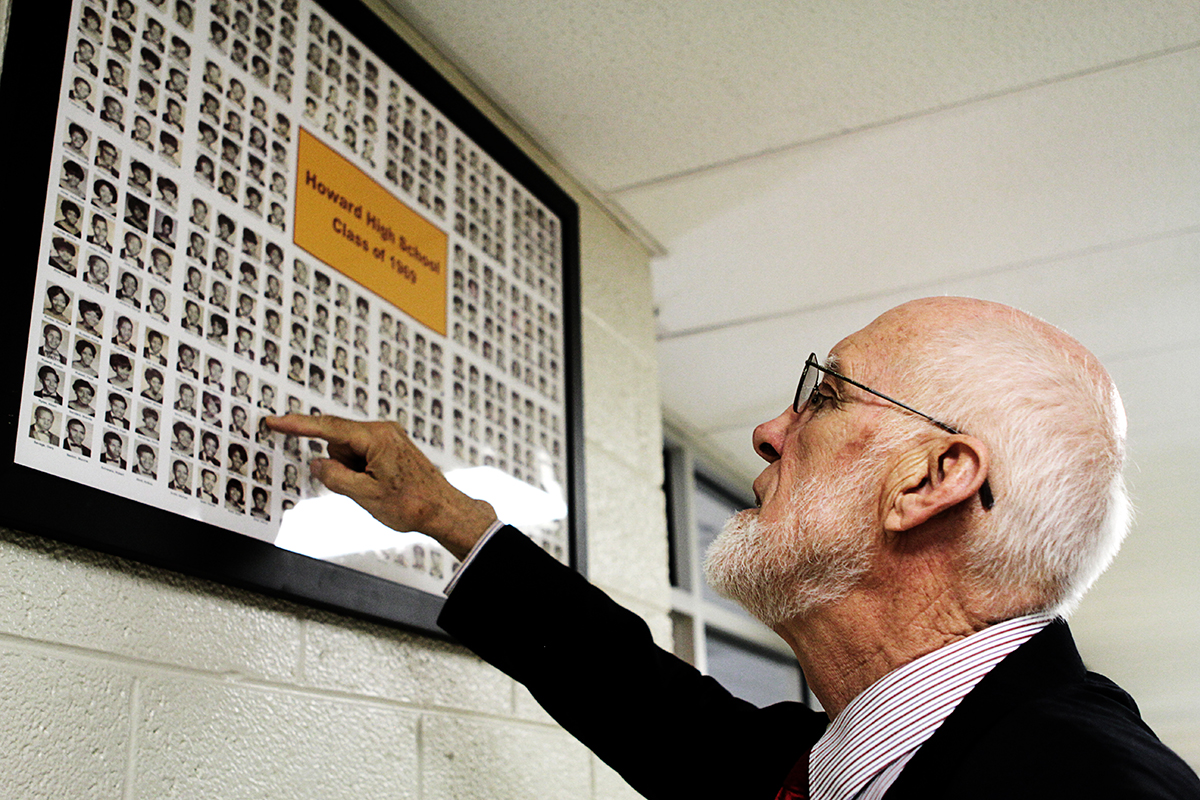

(Bottom) Franklin McCallie with visits a former Howard High School student, Jimmy Seymore, on Sept. 18, 2014, in the school's lunchroom. Seymore, who was McCallie's student from 1968 to 1970, is now assistant principal at the school.

Always the orator, Franklin shared his story with anyone who would listen, at dinner parties, in casual encounters, and when he described the arguments with his father he balled his hand and hit it hard against a nearby surface, raising his voice as his father had decades before.

At nonprofit fundraisers, when magazine photographers would mill around the crowd looking to take a picture, he intentionally paired blacks and whites together in photos. Franklin told his wife that he hoped someone would see the picture in a doctor’s office waiting room and think the image was normal.

He approached blacks whom he didn’t know at events. He invited blacks over for dinner and greeted them at the door with a kiss. At the Bessie Smith Cultural Center gospel concerts he and his wife were often the lone white faces. At the celebration of Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation at an all-black church, in a sea of fine Sunday hats, his bald, white head stuck out.

Franklin’s cousin, Eleanor Cooper, a gray-haired doctoral student, was invigorated by Franklin’s return to the city. She loved his story. She loved how he represented the family name. She studied his intentionality and thought about its impact. Did friendship, kindness, even small social encounters between blacks and whites mean anything at all?

The answer came to her on a radio news report.

“According to the National Bureau of Economic Research, the national wage gap is due in part to the patterns of social interactions that are race based,” she told Franklin.

What research found, she explained, was that even though workplaces are integrated, the social lives of workers are segregated. And this mattered because important information is often exchanged in informal, social settings. Minorities are less likely to learn early on about company developments or tech innovations. They are less likely to know about job openings or ways to improve their professional performance.

At the same time a Reuters/Ipsos poll was released that said about 40 percent of whites and 25 percent of non-whites in America have no friends outside their race. Other research said that out of 100 people in a white person’s network only 1 is black.

In 2013, a time when the country was being led by a black president, the facts were alarming.

Over dinner, Franklin, Tresa, Eleanor and her husband, Mel, discussed the studies and wondered if there was anything they could do.

In the heyday of racism in the United States, social scientists wanted to understand what sustained the prejudiced mind and what broke it, and in the 1950s Harvard University psychologist Gordon Allport presented a simple answer — contact. Exposure, interaction, friendship, these were the tools to combat hate, Allport argued, and decades of research since have echoed his findings. Bring people together, give them equal footing and misunderstandings fall away.

And that was the spark for the idea of hosting dessert conversations at the McCallies’ home. It was simple, but it would work.

Contact.

Curtis Baggett’s wife had talked him into going, and he was nervous as he approached the steps to Franklin’s home.

The 67-year-old retired fundraiser had never had a black man at his dinner table. He had never called a black person his friend. But he was getting older, and when the email came he thought he would step out, do something unexpected.

On the porch of the McCallies’ house Curtis shook the hand of a 42-year-old black man, Charles Adamson. Charles’ greeting was kind and their conversation was warm, and by the end of the night, after hearing Franklin’s plea for friendship, after listening to stories from Franklin’s past, Curtis promised himself to follow through.

Days later Curtis and his wife, Suzy, invited Charles and his family to come to church and share a meal afterward. At first there were awkward moments, anxiety about not knowing what to say. Curtis asked Charles what it had been like, growing up black. Did store clerks look at him like he was a criminal? Had people questioned his intelligence?

He confessed to Charles his own wrongheaded views. He had made fun of blacks, looked down on them, demeaned them with nicknames.

In college and afterward Curtis had little sympathy for blacks, for their struggle to climb out of 250 years of slavery, 90 years of Jim Crow laws, 60 years of forced separation and 35 years of racist housing policy. He didn’t wince when he saw in the newspaper that they were being hosed and bitten by dogs in Alabama. In the years afterward, he felt nothing about the remnants of whites’ sin toward black America, the inequality in the criminal justice system, in education, in health and in workplaces.

The blacks in poverty could pull themselves up by their bootstraps. They could be given a bad lot in life and turn it around, he believed.

“I had little racial conscience,” Curtis said. “I wasn’t concerned about other people who were different. My feeling was that blacks decided that they wanted to live in their area. It was just a tough break. I got a good life and they got a bad life and that is just the way it is.”

Curtis was a church-going Episcopalian, but his morality was flawed, he realized, narrow. Would Jesus have turned his back on the blacks living in isolation all around him? Would Jesus have said they weren’t his people so they weren’t his problem?

On his front porch Curtis regularly drank sweet tea with Charles and, against the backdrop of their developing friendship, his stereotypes couldn’t stand any longer. They talked about everything, about gardening and raising babies and loving wives and living with illness. Curtis had Parkinson’s disease and Charles had end-stage kidney disease.

Curtis let Charles shower at his house after a day of yard work, and Charles said he realized that they were forging a true bond. He told Curtis it was OK if they hugged.

“Hey, you can get close to me,” Charles said. “The black don’t just rub off.”

And when Charles grew sicker and he knew he wouldn’t live without a new kidney, he asked Curtis — a man who had made a living raising money for others — if he would help him raise money for a transplant.

For months Curtis worked, soliciting businesses, calling on friends. Some of his white friends, even family, told him he should be wary of Charles. They suggested Curtis was taking too much of a risk. Charles was playing on their sympathy, using them, some said.

But Curtis wouldn’t let go of their friendship. “We are going to trust in Charles,” he told his wife.

He drove Charles to dialysis where he was hooked up to machines three days a week for five hours at a time. He took him to get his wisdom teeth extracted, attended his daughter’s sporting events. He helped raise $28,000 so Charles could get a new kidney and see his children grow up.

When they talk now, several times a week, they are no longer the two men who cautiously shook hands on Franklin’s porch.

“I love you,” Charles says before he hangs up the phone.

“I love you, too,” Curtis replies.

A few years ago, Curtis said if he would have heard the news of a police shooting an unarmed black man in Ferguson, Mo., he would have thought little of it. Now there is Charles.

Maybe it’s white guilt. Maybe it’s aging and regret. Maybe it’s the way Franklin presented it. Just dessert. Just a friendship. But, much like Franklin felt in 1961, Curtis now prays for people’s conversion.

People might ask him and his wife what point there is to forcing the issue? What does he get out of his relationship with a black family? Well, nothing and everything.

One day, Curtis believes, we’ll all stand before God on this issue. We’ll all stand before God and have to answer for how we treated our neighbor, even our neighbor on the black side of town. We’ll have to explain all the needs we left unmet, all the people we avoided because of discomfort, because of laziness.

“I don’t want my tombstone to say here lies a narrow-minded person,” he tells Charles.

At the end of the year, after hundreds of people had come through the McCallies’ door, a group of 18, half black and half white, sat in Franklin’s living room and dreamed about the future. Other events had spun off of the dessert conversations. A potluck in the heat of July drew nearly 90 people who wanted to follow through with their commitment to be intentional about their new friendships. They brought their children and everyone commented on how natural and easy the day had felt.

Some have left the movement. One woman told Franklin that the meetings weren’t accomplishing enough. The friendships were great, but what were they really solving? Some blacks said they were getting tired of being the token blacks in the room, enlightening clueless white person after clueless white person. Some blacks said friendships between middle class families are easy, it’s the poor blacks that really need to be reached by white America.

What’s next? Franklin asks.

A woman named Eva says she doesn’t feel like they are reaching enough people with their message. A black man who is married to a white woman agrees.

“I go into a restaurant with a strawberry blonde and a cappuccino son and people look away,” he said.

A white lawyer says she is concerned about inner-city education. She heard that some students at a majority black high school didn’t have enough textbooks. Maybe the group should get involved? A black woman who works as a diversity officer at TVA says she feels the group needs to go deeper, discover what racial biases still exist, even those they are unconscious of. Another younger black woman suggests a community-wide conference, round-table discussions on race.

What would this city look like if every business leader had a friend of color, someone asks. We need a Facebook presence, someone says.

“We have to find others,” says Moses Freeman, a Chattanooga city councilman. “This is a lesson we are teaching the whole society.”

Franklin takes it all in. In a way, the chaos of ideas is beautiful. It was inevitable that they come to this point. Over his life he has seen it time and again. Friendship invites caring. And caring calls for action.

He thinks back to Memphis, to the moment he first cared and all that followed.

By 9:30 p.m. they have talked until one elderly participant has nearly fallen asleep, and Franklin tells the group that they will not solve the problem of race relations in America this night. The group scatters, promising to come together again soon.

Tresa places the left-over food in the refrigerator, and Franklin walks the women to their cars.

When he gets back inside, when the night has finally come to a close, he settles into his couch.

For a moment he allows himself to stop, to ponder all that has happened in a year of planting seeds, to feel some joy, some gratification. But just for a moment.

There is still much to do. Hearts and minds in need of saving.